GamesRadar+ Verdict

A lackluster and fragmented game that never really comes together in any meaningful way. In almost every sense that matters, from story to combat, horror, and atmosphere, Alone in the Dark leaves much to be desired.

Pros

- +

The 1920s Louisiana setting

- +

Satisfying early puzzles

Cons

- -

Fragmented story

- -

Dull combat

- -

Weak horror

Why you can trust GamesRadar+

There seems to be some missing layer of polish or finesse to Alone in the Dark's disjointed and occasionally strange choices. The plot's loose threads waft helplessly in a wind stirred up by its fractured narratives, rambling locations, lumpy movement, and dull combat. You can tell what it was aiming for, but the rough edges of its components grind together like the pieces of its broken plate puzzles, pushed crudely back into a plate-like shape; all its fragmented parts forced into place and held there, wearing each other down as they move.

Release date: March 20, 2024

Platform(s): PS5, PC, Xbox Series X

Developer: Pieces Interactive

Publisher: THQ Nordic

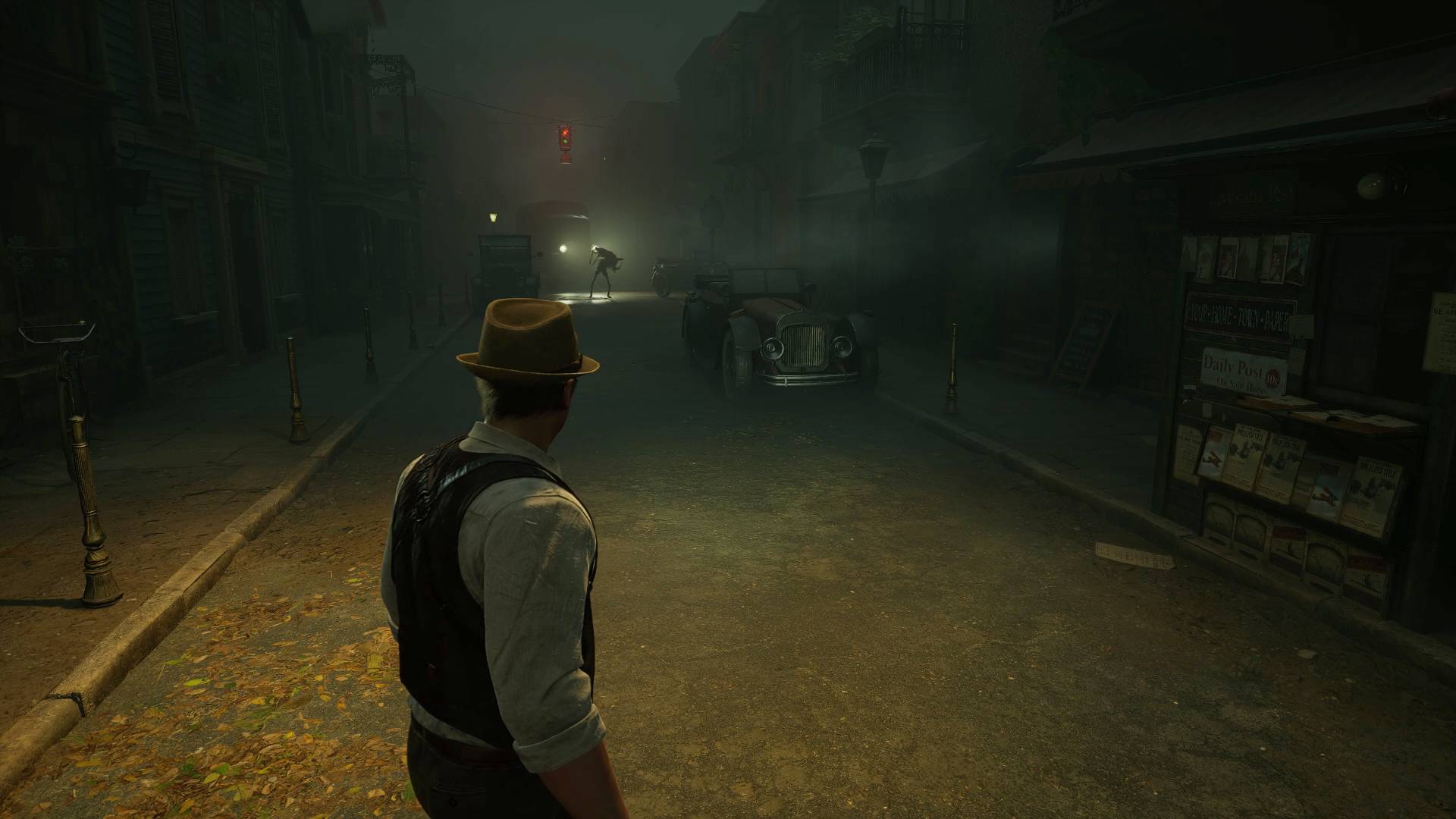

Although even with some other connective tissue to better support and bind it together, I doubt this 1920s-set jumble of Southern Gothic horror, madness, and Lovecraft would fare better. Whether its five-month delay to the original October 2023 release date caused its problems, or smoothed them over somewhat, there's just so much that doesn't quite fit together, or feel like it was ever meant to.

The story sees you playing either as Edward Carnaby or Emily Hartwood, classic characters from the series, and here played respectively by some high profile casting in the shape of David Harbour (Stranger Things) and Jodie Comer (Killing Eve). You're searching for Emily's missing uncle, Jeremy, in Derceto, a big ol' Louisiana mansion operating as a psychiatric hospital that's full of strange guests. Where that goes is almost a matter of interpretation as you explore, thanks to its disjointed segues and progression.

The path ahead

One of the main ways the story moves forward for example is by using an amulet to open pathways into otherworldly memories, effectively jumping you to a new location. Often this can just sort of happen, or the amulet will lead you to a door that perfunctorily takes you there. What connections these areas have narratively are usually squirreled away in notes you can find along the way. To just play, however, without stopping to read it all can make for a very confusing experience, with little in the game world to clarify why any of it's happening.

It feels like the final game has been pulled together in a way that wasn't intended. There are things referenced or highlighted that never come back, or others that just sort of stop being mentioned without a clear resolution. I'd struggle to really explain why any of the other world memory locations are relevant, while characters seem to go about their business with little acknowledgment of anything that's been happening. You can fight a monster in one room, or magically fall from the ceiling in another, and people will just ask how your day's going as you stand there covered in blood, cuts, and dirt.

The entire ending chapter feels like a complete blind side as well. Elements of it are alluded to in notes and dialogue, but not in a way that adequately prepares you remotely for what happens. A second playthrough did make the plotting clearer for me, but only with the benefit of hindsight. The various aspects of Jeremy's disappearance, the Dark Man villain, and the final surprise boss fights all strain against the loose ties in the notes trying to bind them all together. I don't think I've played a story that feels like I need to squint at it to make out the shape before. I wish I could just fully outline the entire plot because I've explained it to a few people and it's met with the sort of slow blinks usually reserved for earnest conversations about faked moon landings or Avril Lavigne dying and being replaced by a double.

Mechanically a lot also suggests this just isn't the game or story originally planned. The amulet often reveals a location, with your character commenting on it and what it might mean, only for an arbitrary door to open nearby, or a new location to just appear around you. You rarely have to do anything specific with the revealed location. There are often things that feel like they were intended to be puzzles or obstacles but were just effectively negated by placing them together - an electrical switch needed to fix a fuse box is just next to it, for example. There are several places where the 'key' needed to progress is just in the same room as the obstacle it clears. An abundance of often generic or non-committal voice lines in some of these instances suggests there wasn't any dialogue for what ultimately ended up in the game. Getting past an obstacle or solving some challenge only to have the hero just mumble 'uh-huh' or 'that's it' can really kill a sense of achievement.

Monster mash

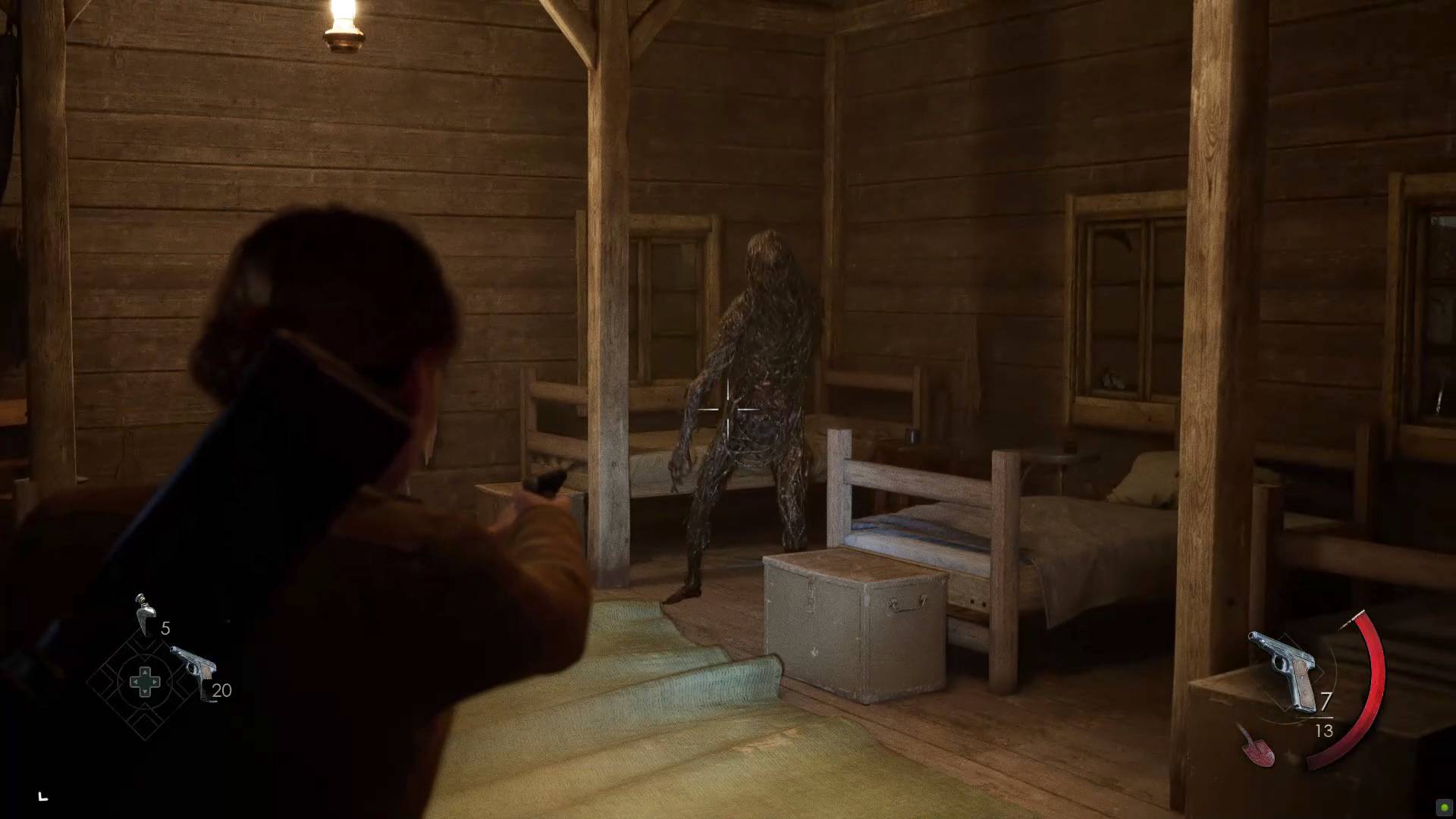

Threaded through the story is a lifeless combat system that does little to help. The shooting model is functional, but combined with sluggish movement and restrictive space, means fighting monsters just feels joyless. There's no meaningful texture to these encounters. Most of the time you'll just meet a single monster, maybe two, that feels like they were placed just to break things up. Other times, when there's meant to be some sort of climax there might be a small horde, at which point it's easy to just get blocked into a corner.

There are odd choices here too, like a melee system that only works if you have one of the many breakable weapons you can pick up - so if you run out of ammo and break the weapon you have left, you literally can't do anything but wait to die. There are also occasionally small stealth sections, but with no clear way to tell if you're safe or detected, there's little point to them. Then there are the odd throwables scattered around that you can only use at fixed locations, initially introduced as ways to distract enemies. You can't store them, only pick them up which then locks you into an aiming animation until you've launched them. The use of a molotov cocktail icon to highlight these objects here is also the only clue you'll get that some are flammable, because it's otherwise never mentioned (non-flammable bricks are also marked with a molotov symbol just to confuse things further).

It's worth mentioning as well that there's never any real explanation for the monsters either. They just appear at one point, to absolutely no comment from the hero, and are then just a thing that happens occasionally. There are plant tendril-like humanoids, skeleton things, tentacle hulks, monster insects, burrowing wormy things, and so on. However, there's no clear theme or any narrative justification I can see for any of them, making them oddly divorced from everything else. They almost feel coincidental.

With everything as disconnected as it is, it means what horror there is never really lands in any meaningful way. This is one of the areas where that missing layer of polish or connective tissue could have really helped. It doesn't take much ambiance to build a little tension, but there's almost no sense of threat, fear, or danger here. An occasional jarring jump cut to move you between worlds is the nearest thing to a scare the game ever really manages. There's rarely a sense of building up to anything, just sections to work through.

There are some nice locations, simply because anything with an early 19th century Southern Gothic feel is a goldmine for horror. While a few early puzzles and objectives add a pleasing satisfaction to the detective work needed as you cross-reference notes and other information. And there is an interesting shape to the wafty fumes of the story that suggest there was something meatier there originally. But the way it all comes together lacks the life or coherence needed to give it any momentum or drive - all too often it simply feels like a sequence of events stacked together to fill out its nine-ish hour run time. (There are minor variations depending on which character you choose, but nothing hugely meaningful from what I've played.) The result is a fragmented tale that never really finds its feet, or hits any of the horror high notes it needs to sing.

Alone in the Dark was reviewed on PC, with code provided by the publisher.

More info

| Genre | Horror |

I'm GamesRadar's Managing Editor for guides, which means I run GamesRadar's guides and tips content. I also write reviews, previews and features, largely about horror, action adventure, FPS and open world games. I previously worked on Kotaku, and the Official PlayStation Magazine and website.