This interview was conducted by Xbox: The Official Magazine

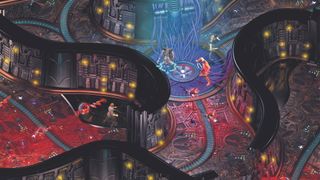

As the western RPG grows ever more cinematic – inspired by BioWare and CD Projekt Red, fuelled by mega budgets – Brian Fargo and his team at inXile are keeping a more modest dream alive. Having shaped the RPG scene in the ‘80s and ‘90s with The Bard’s Tale, Wasteland (proto-Fallout) and Fallout (actual-Fallout) his style of top-down RPGs, soaked through with vivid lore and ideas, fell slightly out of vogue. The fan appetite never waned, however, and with the help of Kickstarter, Fargo is leading a resurgence of the style, first in Wasteland 2 and again in the upcoming Torment: Tides of Numenera. And as we found out, this is not your normal RPG...

OXM: For someone who didn’t play the first Torment, Planescape, could you set the scene for us? What defines what you’re doing as opposed to the western RPG many of us know today?

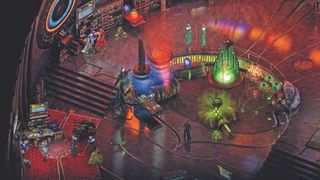

Brian Fargo: Forget Planescape: Torment for a second. If you’ve played either western RPGs or even Japanese RPGs, this is unlike anything you’ve played before. I say that confidently, because Torment, as a concept, is... not high fantasy and it’s not exactly science fiction. It’s this other-worldliness. And you’re not dealing with situations where you’re collecting rabbit pelts. Instead, you might be dealing with a world that is a living organism who you have to feed people who have guilt, right? Or use a trans-dimensional scalpel to cut through him!

To set the stage there is a guy who has discovered the key to immortality – they call him The Changing God. He’s learned how to use people’s life essence: he takes you and he uses you and when you’re done he casts you off. And the cast-off doesn’t know what’s happened – he’s kind of sucked your life out of you, but you’re still alive. You, as the player, start off and you are the last cast-off. You actually appear in the game hurtling from space towards a planet. You can die in the first two minutes of gameplay if you make the wrong decision. Assuming you survive the fall, and do the right thing, you have to figure out what the hell is going on and who The Changing God is.

OXM: Sounds pretty far out...

BF: The universe is super strange – it takes place on Earth a billion years from now. They call it “The Ninth World” – they know there were at least eight other advanced civilisations that came and rose and came and rose. You’re finding technology called Numenera from these previous civilisations. And because it’s so advanced, it’s like magic. It would be like a caveman finding an iPad. He would think that was absolute magic when he turned it on, right? It would seem like magic; same thing here. The universe is super, super strange and unusual and the writing is something that is not what you would typically see in the more “traditional” role playing games.

OXM: In a universe where all this mad and unusual stuff can happen, where do you draw a line? How do you even begin to write something in a world of such possibilities?

BF: I have to say we probably didn’t draw a lot of lines stopping ourselves from being weird. It’s been a real writer’s paradise. Because of the nature of the technology and the sense of magic and the different worlds, we have carte blanche to do just about anything we want. You’re going from one weird situation into another. You never play Torment and think, “I feel like I’ve done this before.” Everything feels unique. And that’s part of its power, I think. When people start to see the presentations, their attitude is like, “This is one of the freshest things I’ve ever seen.”

OXM: We saw some of the stories – I think there was a robot giving birth?

BF: Robots giving birth and then using their babies for bombs, yeah.

OXM: It’s kind of crazy!

BF: Yeah and a computer AI that killed itself – it goes on and on.

OXM: What do you think is the secret to crafting a really good questline?

BF: I think it comes down to characters more than anything. I joke about collecting the ten rabbit pelts, but... you could have a quest where there is a blue door and now you’ve got to find a blue key, right? Not so exciting. But if I have a door, and I’ve got to get a guy through the door and he has agoraphobia and is afraid of public spaces? Fundamentally I’m solving the exact same problem in how to get through a door, but isn’t it a lot more interesting than getting a blue key? That’s the way that we look at it.

OXM: What’s the writing process like in the studio? Do people take responsibility for individual chunks or do you have a big group writing stuff together?

BF: There’s been, gosh, seven or eight different writers on this project. Each one has been given a different area and part of the reason why it’s taken so long is it’s almost like there were seven science fiction books written, and now we’ve got to bring them all together and make them talk to each other in a logical fashion, so the editorial part of it has taken a long time. And one of the writers was Patrick Rothfuss – I think he’s the number two living fantasy author in the world, and he contributed to it. Chris Avellone contributed to it, and of course George Ziets, Colin McComb and Adam Heine who worked on the first Planescape: Torment... Did you ever watch Black Mirror? It would be like if you turned all those stories loose, and have them all in this universe and then try to bring it all together? That’s kind of the process.

OXM: When you build a branching story, isn’t it heartbreaking to create all the outcomes that people are never going to see?

BF: It is, but here’s the thing: role-playing games are my favourite because they can make you feel a broader range of emotions than other genres can. If you want true cause and effect and a playthrough that reflects your personal decisions, then you have to create a bunch of things that they’re not going to see. Otherwise everything is a critical path and we’re not taking into account the decisions you make. I discovered this long ago and it goes back for two decades – we commit to putting stuff in that we love and that we know people are not going to see. In The Bard’s Tale we built this great song and dance number with these Vikings and it was hilarious – and we knew that not everyone would see it, but that’s okay because the ones who do find it are going to love it.

OXM: Torment is a series associated with PC. How do you ease in new console players?

BF: On some level we just make the game we’re going to make and we let the chips fall where they may. We’re not going to think, “Boy, can a console person handle this?” We don’t really think about it that way. I think that where it started to make sense is we saw this sign, the success both from Wasteland 2 – very well received on console – and then Divinity: Original Sin. Those games are just as hardcore as this, so we know there’s an audience there. It might not be as big an audience as a shooter RPG like Fallout, but that’s okay with us. We make a certain type of game and we think people will appreciate it. We don’t adjust for console.

We always try and make sure the game is accessible for someone because it’s pretty dense, right? We put it into early access eight months ago and people said, “You know it’s a little slow getting in, you’re throwing me a lot of information.” We threw them in this battle that took way too long, and so we thought, “They’re right, we need to make it a little less dense in the beginning, less repetitive in combat.” So we eased that up and I think that was the right decision. But that philosophy applies to the PC and the console version; it’s the same issues, it’s the same people.

OXM: Does it being a Kickstarter game change development at all? on paper, it’s more open and democratic, but at the same time, in letting people behind the curtain that maybe carries a risk of having less flexibility.

BF: So there are different aspects to that question. One is, I think there’s a misnomer about the “democratic” process. Backers don’t get to say, “We want vampires,” and vote and get vampires in the game. We’re not going to do that kind of thing. We want them making specific feedback on the experience that we’re creating and we want that genuine feedback. They’re not going to vote to make us make arbitrary changes...

I love this process versus the way it used to be because when I would do the games in the ‘90s - Baldur’s Gate, Fallout, whatever – you’d work on the game, you’d put it out and then you’d get all this really valuable feedback, some of which was easily addressable but we didn’t see it because we were too close to it. And I remember thinking, “If I’d just had this a month ago, this would have been fantastic.”

OXM: Kickstarter has allowed for games that probably wouldn’t have happened otherwise...

BF: I can say with a hundred percent confidence that Wasteland 2 and Torment would never have happened if not for crowdfunding.

OXM: Even with the pedigree of the people involved?

BF: Nope. Never. I’d say that unequivocally. Listen. There’s been a crowd of people that like a particular kind of role playing game, they’ve always been there and they’ve always been super passionate, and there’s been guys like me and guys like Obsidian that love to make them, but we couldn’t do it because retailers were in the way and publishers wouldn’t give us money. So digital got rid of the retailer and crowdfunding got rid of the publisher, and now we get to do them.

OXM: What do you think a video game RPG can offer that a real-life tabletop game can’t?

BF: The big advantage of tabletop games is the social aspect; we’re all sitting around the same spot and a large percentage of the conversations aren’t even about the game, right? Or you’re riffing on some sort of crazy aspect of it and acting immature. And that’s what makes it great – so that’s where the tabletop version has the advantage. Where we have the advantage is we get to hide a lot of the math and the dice rolls so you can focus more on an experience. We have professional writers who have crafted every word.

I think that our ability to set a mood is stronger just because we have ambient sound effects and music playing. You could say a good DM (Dungeon Master) could set a good mood; I would say that it could be close if you got a really good DM, but not all DMs are that strong. So our ability to hypnotise you is stronger in a game. If I’m reading a good book, I forget that I’m turning pages – I’m just there, right? I think the same thing with a really great RPG – if I’m in there I forget that I’m clicking and moving, I’m just living in that world, and I think our ability to immerse you is stronger than what you do sitting around a table.

OXM: It’s great to see a game like this making it onto Xbox.

BF: You know how it is, year after year players and press say, “Why do I see another open world blah blah...?” So we’re trying hard to do some creative stuff. All of the comments on Steam are like, “Yes, you are really doing it, it’s great!” So we’re happy we’re rewarded with good will for what we’re trying to do.

This article originally appeared in Xbox: The Official Magazine. For more great Xbox coverage, you can subscribe here.