The Story Behind Grosse Pointe Blank

We chat to all the stars for this exclusive revisit...

In the 1990s, crime films found their voice. No, really, this lot really wouldn’t shut up.

From Pulp Fiction ’s knowing, poppy chit-chat, to the wordplay running rampant in The Usual Suspects , never had shoot-em-ups gabbed so much.

Until 1997’s Grosse Pointe Blan k, that is. A riotous ensemble in which even its title was stuffed with multiple meanings, Blank had verbal diahorrea and then some. We loved it.

TF towers voted it the 21st greatest comedy of all time, while Blank earned itself high profile fans like Clint Eastwood and, naturally, Quentin Tarantino.

“Johnny worked with [ Eastwood ] on Midnight And In The Garden Of Good And Evil ,” remembers director George Armitage. “He said Clint loved the fight scene, but the scene where Blank and the baby exchange close-ups was so cute, he was on the floor with that!”

“We picked up this script by a guy named Tom Jankiewicz in treatment form,” recalls Cusack, chatting to us exclusively 13 years after his reluctant assassin attended a high school reunion.

“The three of us, my producing partner [ Steve Pink] and my writing partner [ DV Vincennes ] sat around with two Macintosh PowerBooks trying to outdo each other.”

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Let's see how they did...

Next: All In The Writing [page-break]

All In The Writing

Set in a sleepy Detroit suburb called Grosse Pointe (“It could’ve been any town in America,” says Cusack. “It was just a mid-Western town”), the creative team of Cusack, writing partner DV Vincennes and producer Steve Pink forged a dramatic comedy that asked deep questions.

Are we defined by our work? Should skeletons be left in the closet? What’s the value of human life? And, of course, just how cool can we make a shoot-out look?

The trio got a helping hand from director George Armitage, as well, who reveals: “I wrote about eight passes in pre-production. I didn’t take any credit because the Writers Guild is so strict I probably wouldn’t have gotten it anyway, and I was afraid John or Tom or DV would lose out because it’s a very wacky process.”

Though that totals four guys inputting their ideas for the film, producer Roger Birnbaum says that Blank was very much John Cusack’s film.

“There were scenes we were shooting that Johnny specifically, quote unquote, ‘instructed’ the director to shoot a certain way,” Birnbaum reveals. “He was all over this picture. Grosse Pointe Blank , I think, was something Johnny could really take ownership of.”

Predictably, Armitage disagrees. “I doubt Johnny would say that,” he says, “He was thrilled I let him do whatever he wanted.”

Though actor/producers being allowed to do “whatever they want” has sunk many a project (see Town And Country ), it’s precisely because of this constructive, behind-the-scenes churn that Grosse Pointe Blank crackles with incident and intellect.

At its centre is the ironically named Blank, “a spiritual gatecrasher who wants to figure out why his life doesn’t have any meaning” according to Cusack.

“His whole world’s beginning to crumble, so basically you’re watching Martin’s end game, to see if he can survive it.”

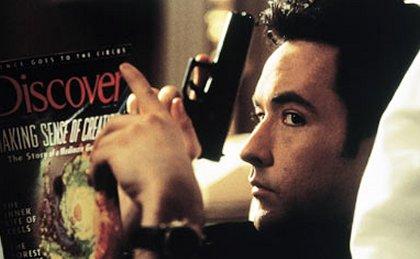

Sneaking Bond references in amid the odd assassin assignment - an early poisoning attempt nods to You Only Live Twice and Guns ‘N’ Roses contribute a fitting 'Live And Let Die' - Blank finds its gun-toting hero in a spiritual malaise.

He talks incessantly to the mirror and a shrink (Alan Arkin) to convince himself he was right to leave high school love Debi (Minnie Driver) behind.

Even the climactic shootout is as much a war of words as of bullets, and though acquaintances both old and new keep telling Blank to slow down neither he, nor the film, ever does.

Next: We Are Family [page-break]

We Are Family

“Johnny likes being around his family and he likes being around talented people,” says Birnbaum. “His family are both.”

Fleshing out various of the film roles with not one, not two, but three of his siblings - Joan, Ann and Bill - Cusack demonstrated Birnbaum's point by playing dress up with the rest of the Cusack clan.

But he also kept it in the film family as well, drafting in old friend Jeremy Piven - whom he knew, along with Vincennes and Pink, from their days in a Chicago youth theatre run by Piven’s parents - to play old high school buddy Paul.

“You want to create an atmosphere where actors can concentrate, where they can get some momentum where they work. That they’re not second-guessed. That they feel like they can make mistakes,” says Cusack.

“All the stuff – all the trucks, all the lights, the cameras, everything that’s there, all this hubbub and all these people walking around, all of it so you can capture a human moment on a screen – that’s what everyone’s here for.

“Get the fuck out of the way. Be quiet. But I don’t say that in front of them. You try to create a little bit of a sacred space.”

No Christian Bale-style rants on set, though, from any of the Cusacks.

“It was an extraordinary process – very civilised,” remembers Armitage. “I was trying to tighten it up and streamline it, and John and the writers had all these wonderful ideas for dialogue and stuff. We would do the scripted version, then we would do a completely improvised version.

“I remember one actor saying, ‘Oh, I never felt such pressure to improvise!’ John went over and chewed him out and said, ‘Are you kidding? This guy is the first director who’s offered the freedom to improvise and actually stuck with it!”

The real on-screen conflicts also formed some of the film’s most interesting beats.

“If you look at people, they’re filled with good and bad,” says Cusack. “Even the worst guy has instincts to be true, to seek redemption. I’ve seen a couple of bar fights and I’ve seen the regret flash into eyes right away.”

This notion of ‘fight first, think later’ was given a fresh twist by Blank in Bobby Beamer’s confrontation with the assassin. The solution, unsurprisingly, comes in the form of a dialogue-driven altercation, rather than one involving fists.

“The scene we shot with the poem was not the scene as written,” remembers Cudlitz, who played Beamer. “John said think of some other way that scene might go ahead and, after racking my brains, I presented a version where Bob, this big jock knucklehead, was in love with him all through high school and had penned a poem about it.

“John wrote part of the poem and I wrote part and we wound up improvising the scene from scratch. It was by far the most creative time I’ve ever had filmmaking. People still come up to me quoting Bobby Beamer and say, ‘Hey, do you wanna do some blow?’”

“The crux of that scene was that Blank was telling Bobby: ‘I’m not your problem, I’m not who you hate.’ but he was talking to himself,” explains Armitage.

“There’s a genuine moment when Blank hugs him and it’s sweet. The purpose of the movie was Blank reuniting with these people who thought he was an oddball before, and beginning to realise there was the possibility he could live another life.”

Next: Making It Up [page-break]

Making It Up

The improvisation involved came with its own limitations. Not that they were anything too drastic.

“If the actors are improvising you ask them, ‘If you’re moving around, just stop for a second when you start to riff and face each other.’ Then you can cut it together," says Armitage.

"If they’re moving you’re in trouble. It’s going to look jumpy, it’s going to jar the audience out of the movie, but there’s ways to do it so it looks like it’s smooth. I mean there were a few things that bothered me, but nobody else seemed to notice.”

In among the maelstrom of witty asides and worrisome monologues, several moments of improvised magic stand out.

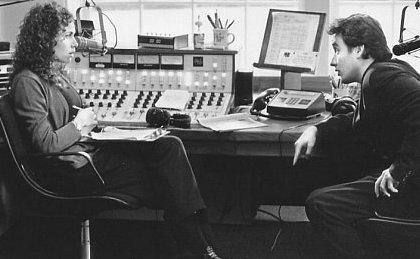

When Blank strolls into Debi’s radio booth unannounced after ten years, she pulls him apart live on air, pausing only for an angry, longing kiss.

“It was just wonderful, completely out of the blue,” says Armitage. “You should have seen the smile on Johnny’s face afterwards.”

Cusack wasn’t the only one enjoying himself. “Danny [ Aykroyd ] was menacing and he completely got into it,” says Armitage.

“He’d never had that type of role before, so he did a lot of research. He was the one who said the assassins will have like ten guns with them and they’ll keep firing them off, then throw them away and pull out two more. He had an absolute ball.”

Not wishing to be left out of the gun-slinging, Driver requested some firearm action too.

“I said OK, let’s figure something out,” says Armitage. “So when she’s hiding in the bathtub during the final shootout she fires off a round because she wanted to join the fun. Honestly, I can’t tell you, it’s too bad you weren’t there. It was an absolute joy, we were playing the whole time.”

Next: Fighting [page-break]

Fighting

For the film’s flippy fight scenes, Armitage recruited Benny ‘The Jet’ Urquidez, a martial arts world champion who has nine black belts under his, um, belt.

“John’s been my student for 16 years, he mentioned my name in Say Anything ,” says Urquidez. “He’s an excellent kick boxer. We still train together five times a week.”

The visceral confrontation between Blank and a fellow assassin in the school hall was put together by him “in two days. Usually it’s a week, but John knows he can throw hard at me and I can absorb it. It was no big deal.”

Roger Birnbaum found the situation slightly more stressful:

“It wasn’t shot with wild abandon, it was done very, very carefully. There were stunt coordinators around, you know, it wasn’t something where we said, go on, go at it guys, best man wins. It was thoroughly controlled.”

“He was the world kickboxing champion!” chuckles Armitage. “I said ‘Listen, Benny, do whatever you want to do, but please don’t hit the star!’ You don’t want to break a nose because you’re going to get shut down for a week or three. We had some close calls.”

Urquidez remembers a particularly close one:

“John kicked me so hard the first time, with that sidekick going into the lockers, that my feet completely came off the ground cause he’s so damn tall.

“My knees came out from under me and I went straight down. So I had to tell him where to kick me. The second time he kicked me so hard and fast that my back hit the dial on the locker and I had the numbers drilled into my back, an imprint.”

Cusack’s gun-ho about the whole approach. “I like to take risks,” he explains. “With acting, you wanna see if you can get into trouble without knowing how you’re gonna get out of it.

"It’s like the exact opposite of war, where you need an exit strategy. When you’re acting, you should get all the way into trouble with no exit strategy, and have the cameras rolling.”

“We each got our bruises but such is life,” says Urquidez. “I never broke a nose. I’m all about safety. I kick a cigarette right out of your mouth ten out of ten, hundred out of a hundred, that’s how good I am.

"I can go full blast and stop two inches in front of your face, my foot or my hand, so if I hit you it’s because I meant to hit you.”

This ferocity of purpose transferred unforgettably to the screen, particularly at the fight’s messy end, where Blank rams a ballpoint into his opponent’s jugular.

“Quentin Tarantino said it was probably the best fight scene he’s ever seen, and I’m not sure of that, but it was certainly a beautiful job,” says Armitage.

“They wanted the reality of it, and I said, ‘OK, well this is the reality of it, the fight don’t end on the ground, it ends when it ends, and John took me right to that point.’” says Urquidez. “I’ve died many ways onscreen, but I’ve never died with a pen in my throat before!”

Armitage remembers it just as fondly: “I have that pen. A Mont Blanc. I still use it.”

Next: On Location [page-break]

On Location

Shooting Blank necessitated some clever camera trickery, which turned Los Angeles into their sleepy little suburb. The cast and crew ended up doing all but half a day’s filming in the City of Angels.

A testament to the team’s work came when Detroit-based Jackie Brown author Elmore Leonard failed to notice the difference.

“Elmore Leonard thought the whole film was shot in Grosse Pointe ,” says Armitage. “The newspaper reported how nice we were, how we never blocked traffic – which would have been unusual because we were in a helicopter the whole afternoon.”

Birnbaum remembers that the tight schedule meant there was little time to pause and reflect.

“We didn’t have many shooting days, we just had to fly through this thing,” he said. “I think the pace of it reflects the energy of the characters. They look like they, at any moment, could explode from the angst and violence going on inside them.”

Armitage recalls a moment of rather more literal explosiveness:

“My biggest memory of the 7-Eleven shootout [ in which Cusack faces rival Felix Lapoubelle (Benny Urquidez) ] is that the place was wired to blow.

The explosives were being set up while we were filming, so it was a little nerve-wracking. The whole place could have gone up at any time. If you dwell on something like that it really amps up the drama.”

Despite the time crunch, Armitage still found time to slip in a little wink to other crime flicks...

“I called Quentin Tarantino and said, ‘Could I use your lobby card of the Pulp Fiction cast?’ So we wired that with squibs too and shot it up!” he laughs. “It was a homage, a tip of the hat to Quentin.”

Tarantino was keen on a cameo, but that never materialised. “He wanted to be shot or blown up or something,” recalls Armitage.

Next: Grosse 2 [page-break]

Grosse 2

Made on a respectable budget of just $15m, Grosse Pointe Blank opened on 13 April to the trill of $6m. It went on to take almost $30m Stateside, a tidy sum for the time.

Since then, Cusack has gone on to suitably intelligent indies like Being John Malkovich and High Fidelity , while seemingly cashing in for a nice paycheque with the questionable likes of 2012 .

Director Armitage made The Big Bounce with Owen Wilson and Morgan Freeman, which all but copied Grosse Pointe Blank ’s formula.

“It was a very interesting process,” he says. “Owen would improvise while Morgan stuck to the script.” It was left for dead at the box office.

As for the possibility of a Grosse sequel, producer Steve Pink says it could happen if the interest was there.

“I think a sequel would be great,” he says. “There was talk about it for a long time. I mean I would make a Grosse Pointe Blank 2 . I would do that. I'd love that!”

Could Blank be due an invitation to his 20 year high school anniversary? Or could somebody be holding a Kill Bill -style revenge agenda since the last one? That baby is probably of age now...

Like This? Then try...

Sign up for our free weekly newsletter here .

Follow us on Twitter here .

The Total Film team are made up of the finest minds in all of film journalism. They are: Editor Jane Crowther, Deputy Editor Matt Maytum, Reviews Ed Matthew Leyland, News Editor Jordan Farley, and Online Editor Emily Murray. Expect exclusive news, reviews, features, and more from the team behind the smarter movie magazine.