"We were beginners when it came to online games": The making of Monster Hunter

Kaname Fujioka tells Retro Gamer how his team began a series that laid the groundwork for connecting hunters together

At the turn of the millennium, console online gaming was the industry's new wild frontier. Sega had blazed the trail with the Dreamcast, albeit with mixed results, no less due to the console's own short lifespan. But with the PS2 at the peak of its popularity, Capcom embarked on a three-pronged strategy to embrace online gaming.

"Each game had a different concept of how to utilise online connectivity: the racing game Auto Modellista, the horror spin-off Resident Evil: Outbreak and, finally, the multiplayer action game Monster Hunter," explains Kaname Fujioka, who would go on to direct the latter. "So the series really came about from our early efforts to develop games in the nascent online space."

Fujioka had joined Capcom in its arcade heyday when Street Fighter II was the king. As a character animator and motion designer, he cut his teeth in the company's arcade division on titles like the Darkstalkers series before leading on character creation for lesser-known arcade-only release Red Earth. So an online-specific game, one set in a vast 3D world of roaming beasts, was a huge departure, which he would be the first to admit.

"We were beginners when it came to online games, so we took inspiration from any and every online title we could," he says. "The first step was in understanding the difference in how online games such as multiplayer online games and MMORPGs were structured compared to ordinary offline games. We researched titles like Final Fantasy XI, Diablo, Ultima Online and Phantasy Star Online."

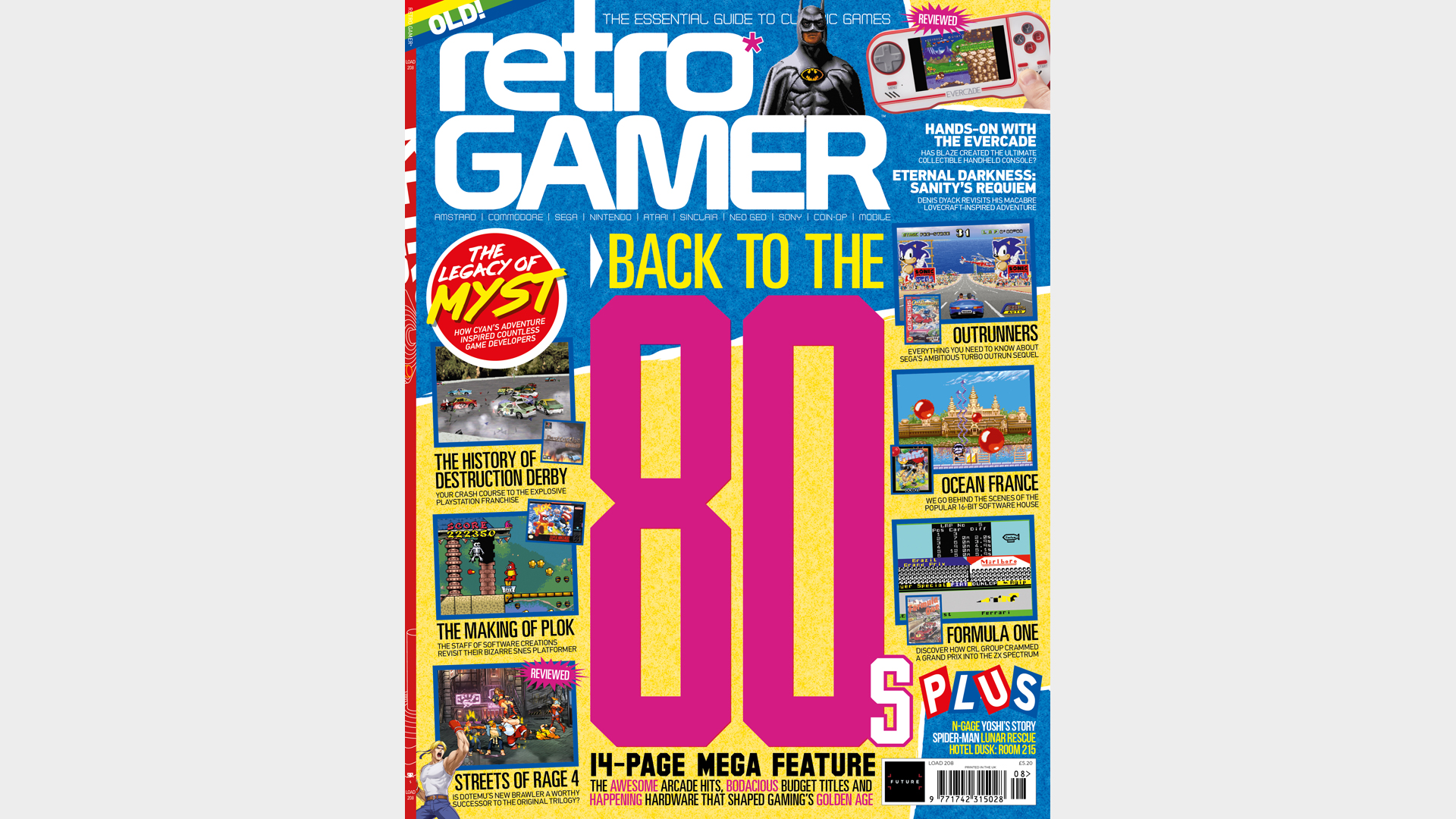

If you want in-depth features on classic video games delivered straight to your doorstop, subscribe to Retro Gamer today.

While he mostly cites MMORPGs, Monster Hunter was a different kind of beast. First and foremost, and true to its title, it's a game about hunting monsters as you work your way up the food chain to take on the most gargantuan apex predators that could send most players packing with just a swipe of their claws or a swing of their tails. There was no levelling system, rather your hunter's strength grew based on the armour you were able to craft from the carcasses of creatures you felled.

Hunts themselves were also not structured as dungeons but rather across vast arena environments teeming with flora and fauna that felt like its own ecosystem. Perhaps most unusual for a developer known for making games with big hit bars, there's no way of seeing how much health a monster had; you instead had to read their behaviour, like when a gravely wounded Gendrome starts limping back to its lair.

It's perhaps no surprise that Fujioka's background meant that animations played a vital part in the feel of Monster Hunter, which also set it apart from more fast-paced hack-and-slash action games. Players instead learned to understand and respect animation frames, whether it's the swing of a weapon, the time taken to neck a potion, or a monster attack that knocks you back or sends you flying. All of this sought to immerse the player in a grounded realism seen in few games at the time – certainly not in MMORPGs reliant on menu commands, cooldown timers and mouse clicks.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"All of the different styles of online games that we were looking at had their pros and cons," Fujioka explains. "So I think that the biggest challenge in designing Monster Hunter was in understanding the possibilities and restrictions that came about from each concept."

It was neither a stats-heavy RPG nor a hack-and-slasher you could mash away at, which would be a surefire way to get yourself killed. Of course, button-mashing was out of the question for more bizarre reasons: instead of face buttons, Monster Hunter mapped its attack inputs to the PS2 controller's right analog stick. Incidentally, controlling the camera came from the d-pad, meaning that players who wanted to move both their character and the camera at the same time developed an awkward hand technique infamously coined 'the claw'.

As baffling as the control scheme sounds now, using the right stick for camera movement was far from the default option at the time, apart from in FPS games. In fact, this era saw Capcom taking many experimental approaches to navigating 3D environments, as demonstrated in Resident Evil 4 and God Hand. "On PS2, we pursued the concept of a combat control system which felt analogue and responsive, leading to the unique style of using the right analogue stick to swing your weapon," explains Fujioka as he also justifies that subsequent entries also attempted to leverage the hardware's key features into input, such as swinging the Wii remote in Monster Hunter Tri or using the 3DS touchscreen.

Analog swing aside, Monster Hunter's other features nonetheless would remain part of its core DNA that made it unique to any other kind of online multiplayer game. Its structure also came down to working around hardware limitations, such as how these huge hunting arenas had to be broken up into smaller zones separated with loading screens. Indeed, everything, from split single-player and multiplayer modes to quests, fragmented into more digestible chunks. "We were ultimately able to arrive at our own unique version of what Monster Hunter was", says Fujioka. "That fundamental understanding of what concepts were viable and how they meshed with our intentions was key."

Monster mash

Then, of course, there's the star attractions themselves, the monsters. From the harmless herbivore Aptonoth you slay for meat to the stone-armoured flying fortress that is Gravios, Monster Hunter contains about two dozen types of monsters. Although there's a rather 'Jurassic' flavour to a few of them, they also cover a distin

ct breadth of species that fit in each of the game's regions of varying climate and terrain. "Since the hunters are basically avatars of the player, it was much more important that the monsters be more strongly and uniquely characterised," says Fujioka, "The monsters are designed so that their unique aspects come across easily in their silhouette and colouration. I think that approach is partly why many monsters have been so memorable and beloved to players over the years."

Incidentally, Fujioka tells us his favourite monster from the first game is the Rathian, the flying wyvern and her poisonous tail that is essentially the other half of the title cover star, Rathalos. "Rathian was the first large monster designed for the game and that process became a blueprint for subsequent large monsters. It's just a really challenging but fun monster to hunt!"

Yet it was also important for the game to maintain a structure of progression, as series producer Ryozo Tsujimoto explained in a 2014 interview with Kotaku: "You don't want a very powerful-looking enemy right at the beginning because it would be silly to be able to defeat him really easily, so earlier on we [wanted a ]ant sort of a comical element, so that you're not fighting an endless succession of really powerful-looking monsters early on."

Your first few quests centre on gathering supplies as you learn to craft useful items like meat and potions. Your first real hunt sees you slaying a pack of mostly annoying Velociprey before you graduate to face the larger Velocidrome, still ultimately small fry compared to the later wyverns. Progress is a slow methodical approach requiring patience not unlike the bespoke animations, but it eases in the player from fledgling hunter to a fearless master over monsters. Ultimately, the real magic came from joining forces with other players online.

Suddenly with four hunters laying into the thick hide of a Diablos, the odds don't seem quite so impossible, as one keeps it busy while another knocked down and close to fainting can catch their breath to heal or resharpen their blade. While communication was limited unless players had a keyboard peripheral, Monster Hunter included the ability to use gestures – a feature now widespread in all online games – the game's 'prance' remaining its most charming and unique. According to Fujioka, this was a late addition during development.

"For time reasons, most of them are based on the motion designers doing their own motion capture performance and directly putting that recording into the game. I think that's what gave them a nice degree of looseness!"

The online element was certainly the major positive given to Monster Hunter by its harsher critics when it released in 2004, arriving the following year in Europe. While reception was mixed overall, with Game Informer describing its control scheme as "horrific", Edge scored it 8/10, praising it as "an excellent exercise in humility and cooperation, and one that should not be passed by".

It was Capcom's best online game for the PS2 by default, mostly because both its earlier efforts Auto Modellista and Resident Evil Outbreak arrived in Europe stripped of that USP. Even then, the lack of widespread broadband connectivity meant few were able to fully appreciate the experience as intended. What ultimately turned the game's fortunes around from being a curio slipping into obsolescence was a change of platform, when the game's previously Japan-only expanded re-release was ported to the PSP in 2005, released in the West as Monster Hunter Freedom.

"A portable system like the PSP lets people use ad-hoc local networking to experience that great multiplayer action together," explains Fujioka. "Being able to get across to people what was so great about Monster Hunter this way was a huge boost to the series."

This success, which later continued on the Nintendo 3DS, however, was largely in Japan where portable gaming was much more commonplace with its younger player base in the playground or on the train. Nonetheless, subsequent entries would continue iterating on the series' compelling formula that when the series finally got the attention of the rest of the world jaded by the modern monetising machinations of big budget games, it was like a breath of fresh air.

Too big to fail

"Since the hunters are basically avatars of the player, it was much more important that the monsters be more strongly and uniquely characterised."

Kaname Fujioka

While Monster Hunter World is finally able to take advantage of current-gen technology to easily connect players into seamless hunting environments as well as streamlining some of the series' more archaic quirks, its core DNA of capturing the thrill of the hunt has remained intact. Now serving as the series executive director, even Fujioka can't quite believe how life-changing the series has been for him, not just because it's now only behind Resident Evil as Capcom's best-selling franchise of all time.

"Compared to my days as a designer, when I would immerse myself in my work so much that I barely got outside for fresh air, being a part of Monster Hunter has given me the chance to step out and come into contact with all kinds of people," he says. "The experiences I've had through the series have enabled me to see things from varied points of view, for which I'll be forever grateful."

Although the original Monster Hunter feels like a fossil that will remain unknown to the series' millions of new fans, it's incredible how much its spirit hasn't been lost in subsequent generations, which still tap into the joy of cooperation and triumphing in the most formidable hunts. That's worth a prance.

This feature first appeared in Retro Gamer magazine issue 209. For more excellent features, like the one you've just read, don't forget to subscribe to the print or digital edition at MyFavouriteMagazines.

I'm a freelance games journalist who covers a bit of everything from reviews to features, and also writes gaming news for NME. I'm a regular contributor in print magazines, including Edge, Play, and Retro Gamer. Japanese games are one of my biggest passions and I'll always somehow find time to fit in a 60+ hour JRPG. While I cover games from all platforms, I'm very much a Switch lover, though also at heart a Sega shill. Favourite games include Bloodborne, Persona 5, Resident Evil 4, Ico, and Breath of the Wild.