2Dark digs up survival-horror’s roots with murder-clowns, chain-smoking babysitters, and a lethal save system

The man who created modern survival-horror is not happy with the way things have gone. Having designed 1992’s Alone in the Dark - the first 3D horror game, which pioneered the idea of polygonal characters roaming pre-rendered monster mansions four years before Resident Evil shuffled onto the scene – Frederick Raynal has since avoided the genre he defined.

He describes his game’s sequels, which he didn’t work on, as “shit”, and decryies the overall genre’s shift toward protagonists who can capably (or at least semi-capably) combat the supernatural threat they face. And he has a point. After all, how is something horrific if you can shoot it down? How is a zombie any different from a soldier or criminal goon if a bullet is the answer to all three? Ultimately, how can any threat be defined as true horror if you can hold your own as its equal?

So with his 24-year delayed return to the genre, he’s taking a different tack. His hero - a worn-down detective on the search for a series of murderers a few years after losing his own family to the same - is desperately vulnerable, as you might expect, but Raynal isn’t stopping there. Because if basic self-preservation isn’t enough too keep a player scared once they get multiple hours into a game and become au fait with its systems – seeing through the Matrix is an immersion problem in almost all games at some point – then how about giving us something else to worry about? How about saving innocent children from serial killers?

Now, at this point – and repeatedly during my demo – Raynal is at pains to emphasise that he doesn’t want to be seen as the guy making ‘the game where you kill kids’ – yes a stray gunshot will have the expected effect, but it will also result in an instant game over. He is planning to use dark, adult themes in 2Dark, and the use of children as a gameplay and narrative mechanic is intended to work to serious effect, not macabre novelty. In fact he’s genuinely impressed by how playtesters (older ones, especially), and even himself, have remained stressed and protective about the fate of their diminutive charges long into the game, often refusing to complete a level and move on without a 100% rescue stat, even when the game’s demands dictate that they easily could.

Saving the kids, not sacrificing them, is key. There’s no intent of malicious humour here. If the kids weren’t emotionally important to the player, the entire conceit behind the game’s design would rapidly fall apart.

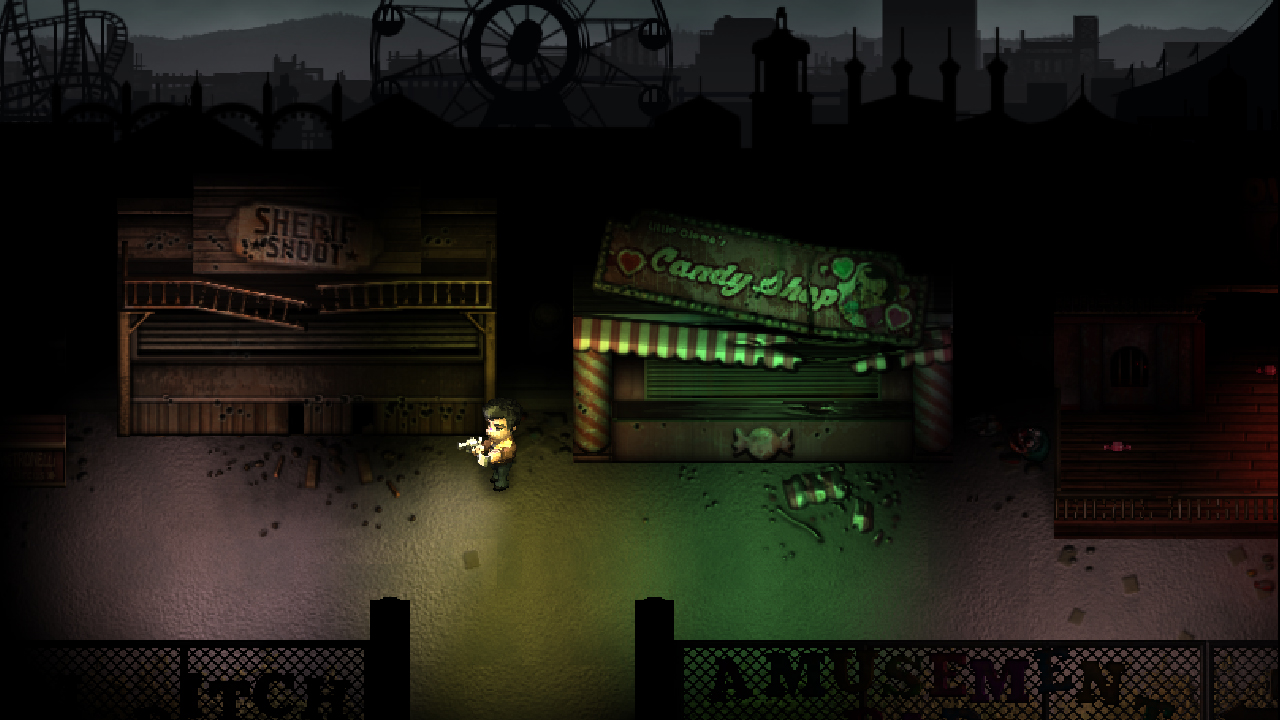

And so rescue them you shall, creeping your way through multiple, themed labyrinths filled with darkness and death, as you track the kidnapped younglings and attempt to lead them back to the light. But this being a Raynal game, you won’t be getting much help. Worse than that, in fact, the systems that usually assist and expedite in any horror adventure – heck, almost any video game – will often conspire to screw you over themselves. But I’ll come to that in a moment.

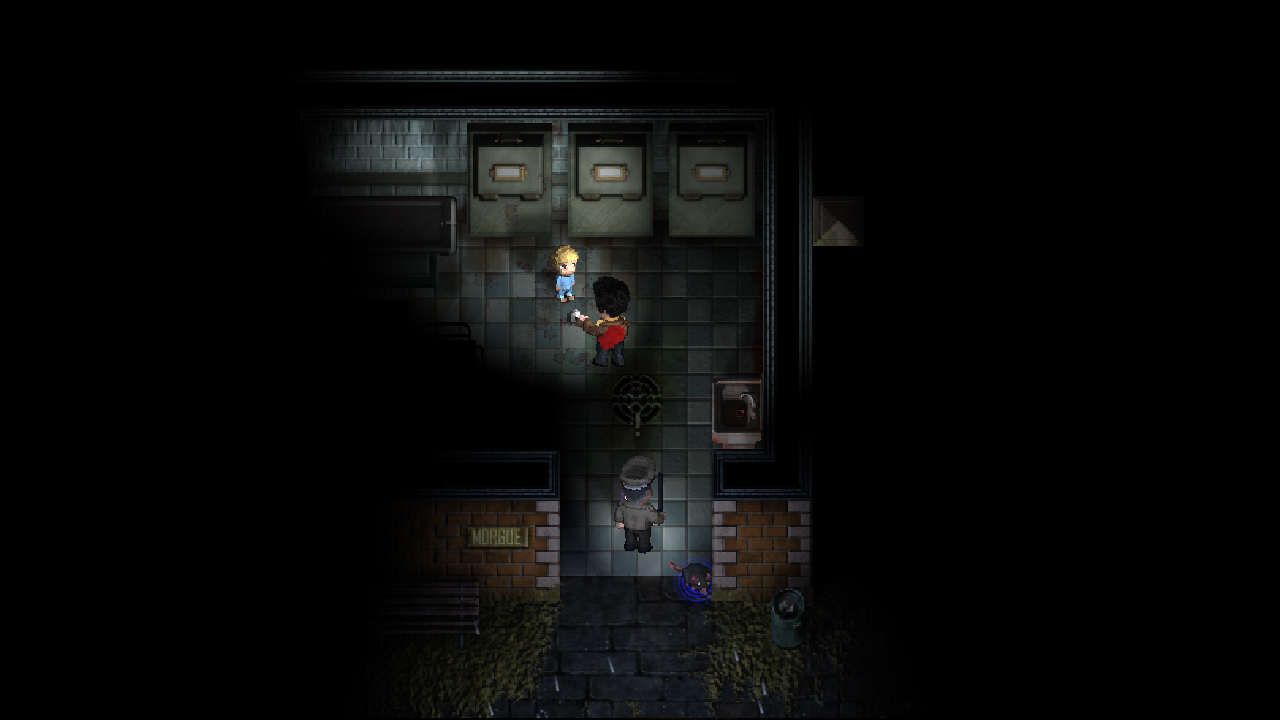

As you work your way through these sprawling dungeons, your key weapons – and I use the word very loosely – will be darkness and quiet. Both will mask you from the patrolling enemies at large, with visible indicators of the noises you make – a pulsing blue radius and temporary footprints tracking your path – being your key gauges of (relative) safety. Beyond that, it’s up to you. 2Dark, you see, is entirely systemic. It is scripted only so far as its developing story. On-mission action is the product of reactive AI, responding dynamically to an ecosystem of stealth, misdirection, and the use of many, many adventure game-style inventory items. I saw a side-bar of 18 in play during my demo, but Raynal told me that the inventory can be expanded to fill half of the screen, implying dozens if not hundreds of ways to play with the world.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

And when I say “It’s up to you”, I really mean it. You won’t be given the total number of kids to be rescued from each killer’s lair. You’ll only find out if any are missing when you try to exit. You won’t be given any indication of their locations, and will have to track them down via risk-and-reward exploration. That huge, empty, pitch-black corridor? Is it really empty? Is there a victim hidden away down there somewhere? Or just a silent, as-yet sleeping enemy?

And that guard on patrol? Should you quietly slink away from it, potentially being forced down a new route? Or should you sit tight, hoping to remain unnoticed until it passes? Or, in fact, should you brave following it? Maybe it will lead you to somewhere useful if you can survive the pursuit. Maybe, if it bumps into a colleague and strikes up a conversation – just as likely as not in 2Dark’s emergent crucible - you might even learn some useful information.

For all of 2Dark’s cartoonish, voxel simplicity – Raynal tells me the art style was chosen so as to ensure that the game’s themes and tension do not become too oppressive; ditto the colourful killer clichés, the real-life versions being ‘just sad’ upon research – there seems to be a lot of complexity going on in its systems. Although primarily a stealth survival game, there’s definitely a hint of Hitman and Thief about its open-ended reactivity. And most interesting of all, that doesn’t end when you find your would-be rescuees. In fact at that point, it scales up.

Once they’re found, you need to lead the kids back to the level entrance, and they’re not necessarily going to make it easy for you. They all have individual names and individual personalities, and while that will surely make for a great deal of emotional attachment, it will also make them a nightmare to wrangle. Some will be eager to follow you. Others will get bored. Others still will get upset. They even might start crying, which has obvious traumatic implications in a sound-based stealth-world. Some might get tired, and stubbornly refuse to move until negotiated with and bribed with (a finite supply of) candy. And if you get really unlucky, you might find a kid with Stockholm Syndrome, who wants to stay and makes active attempts to do just that. All of them are different, and all of them have their own dialogue, described as ‘sometimes funny, sometimes tragic’.

But still, at least a player-controlled, ‘save anywhere’ system will help if things go drastically wrong, right? Well no. Because in 2Dark, you save by smoking a cigarette from your inventory, a new, far less healthy spin on Resident Evil’s old typewriter ribbons. That’s all well and good for a while, but if you save too many times, burning through the required amount of smokes to do so? You’re likely to start coughing. And coughing is noisy. And you see where this is going.

2Dark is a highly intriguing game, made of a very promising and potentially refreshing set of survival mechanics, wrapped in what could an incredibly vibrant, free-form package if all of the emergent stuff comes together as hoped. But the biggest question right now is possibly the coherence of the game’s tone. Raynal’s unswerving dedication to integrating taboo themes – both narratively and mechanically – is certainly admirable in a horror genre too often dominated by the politeness of ‘safe’ zombies and barely-threatened action heroes, as is his sensitivity to the presentation of his ideas. But can they maintain their potency amid a cartoon, 16-bit style translation?

Will the emotional attachment Raynal hopes to achieve let players see through the softer visuals, just as those visuals initially hope to get players past the grim themes and into the game? If those elements can indeed bolster each other rather than cancelling each other out, then we could be looking at a heck of an engaging horror surprise. Either way, we’ll find out when 2Dark releases on PC, PS4 and Xbox One from later on this year.