7 rules Alien: Covenant needs to follow if it’s going to be a legitimate Alien film

Alien: Covenant has Aliens in it. It has the word ‘Alien’ in the title – which to be fair, is a big improvement over its in-denial precursor, Prometheus. But does that make it an Alien film? Not necessarily. And I currently find myself conflicted about its potential to be one. On the one hand, the film’s poster is a seething, biomechanical nightmare of atmosphere and abstract body-horror, every bit a deliberate evocation of the almost ethereal sci-horror that artist HR Giger drilled into with the original film’s designs. On the other hand, the first main trailer depicted, well, a film with Aliens in it.

It’s not that it looks bad, strictly. It’s just that, with its wide, grassy, daylit spaces, thundering, chaotic action, and multifarious instances of CG xenomorphs using their heads like bombastic, exo-skull battering rams on spaceship windows, it doesn’t feel quite right. It all just feels a bit lacking in the quintessential ‘Alienness’ that made the original trilogy just a profoundly affecting – and incredibly distinct - sci-fi terror experience. It might all be turn out just fine of course. Maybe that trailer is just an attempt to cultivate a more boom-ccentric impression in order to draw in and ultimately disappoint the lucrative Michael Bay audience. I hope so. Ridley Scott, after all, invented Alienness, so he should know what he’s doing.

But if he’s forgotten, here are the fundamental elements, themes and concerns that Covenant needs to preserve in order to earn that extra word in its title. I’m sure Ridders has time to squeeze them all in before the premiere next month.

Atmosphere and tone above all else

Seriously. Above all else. There are many facets of character dynamics, subtext, and horror themes that an Alien film needs to nail, but if isn’t the right kind of stylish going in, it’s only going to feel half-authentic. And I’m not talking about the modern, overly glossy, swirling-cameras-and-no-one-can-blow-their-nose-without-going-into-bullet-time definition of cinematic style. Paul Anderson tried that in Alien vs. Predator, and succeeded only in creating Alien vs. Predator. The system doesn’t work.

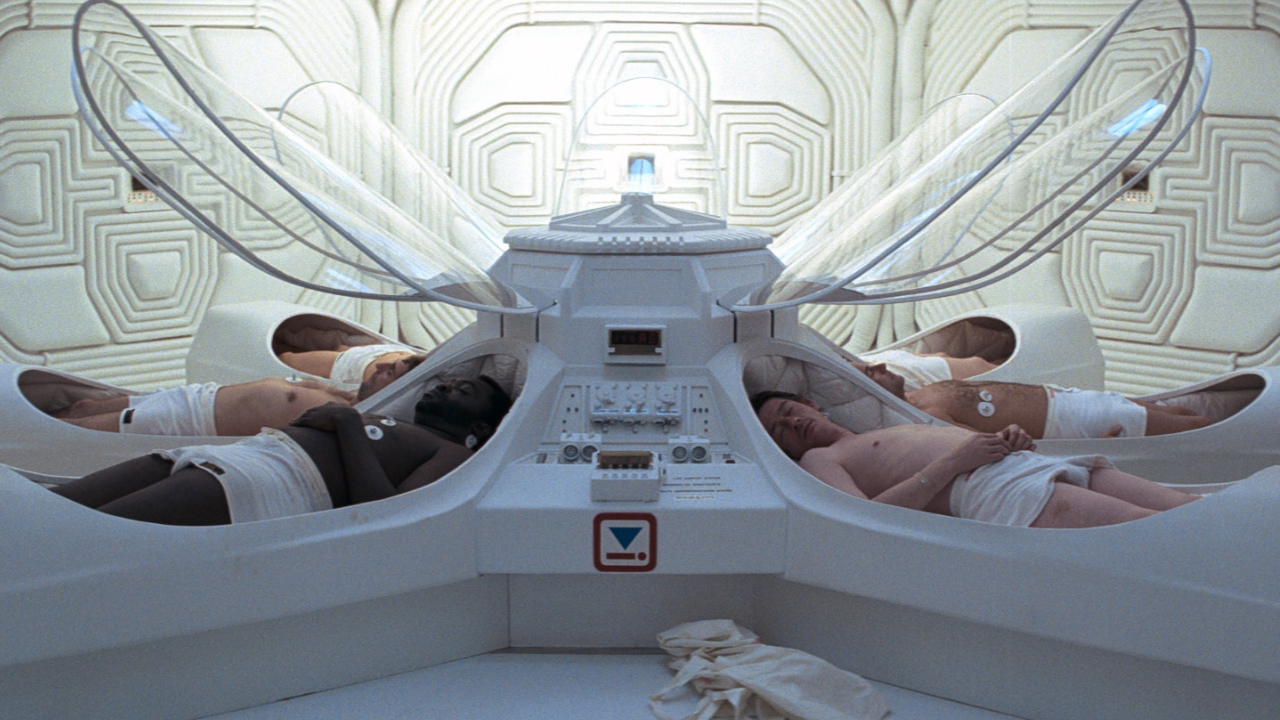

No, in Alien movies, whether set on distant space-tugs, dilapidated off-world colonies, or gigantic boiler-room holding pens for murderous bald men, there’s a certain density of tone, a thick, heavy ambience and an omnipresent sense of tangible, oppressive hopelessness to wrap and bind everything that ensues. The Alien universe is the most quintessential version of what is often referred to as the ‘Crapsack World’ trope, a place so nihilistically grim that the appearance of a murderous, relentless, parasitically chest-bursting, biomechanical alien species isn’t so much a stand-out horror as much as ‘something that was probably bound to happen at some point’. It’s an oppressive, uncaring, cold, corporate-controlled meat-grinder, where survival is as good a day-to-day goal as any, and where, while there might be nice, clean, peaceful, sunlit places somewhere, no-one seems to have seen one in quite a long time.

This stuff is fundamental to amplifying the horror of the xenomorph. By bedding it down in a grotty, grounded, believable, but altogether miserable world, it adds a mournful, embattled futility that makes every explicit danger and struggle feel at once more poignant and more entirely fatalistic. But it’s not just about the grimness you put in the world. It’s about how you present and reveal it too. Because you also need to…

Go slow-burn with the pacing

Unless you’ve watched them recently, Alien, Aliens, and Alien 3 are probably way, way slower than you remember. And it’s important that they are. Even the middle film, which most (erroneously) label ‘the action one’, holds out for over an hour before revealing a xenomorph. The original Alien’s dialogue-free opening five minutes are one of the best pieces of ambient scene-setting in cinema history, all slow panning shots, lingering focus, and deliberate fade transitions, as the silent shadows of the Nostromo gradually stir into life. After that, the film’s opening act is typified by underplayed, almost documentary-style characterisation and low-key conversation. And Alien 3 is pure character drama, the monster itself almost a fringe danger, lurking on the periphery of the interpersonal trauma, as Ripley takes stock of what she’s been through and been forced to become, while wrestling with the challenges of under-equipped, disbelieving, progressively terrified, deeply flawed personalities.

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Again, it’s all about grounding. By taking the time over their world-building, and pushing characterisation to the fore, Alien films make the eventual, otherworldly invasion all the more profound and believable, yet also more jarring and, well, alien. With more time afforded to smaller-scale, more nuanced character interplay, they also give themselves the freedom to craft more real, less ‘Hollywood’ personalities, liberated from any obligation to immediate, quick-fix, broad-strokes archetypes by virtue of having the time to infuse sci-fi horror with real, carefully paced storytelling. There are rarely any straightforward character tropes in an Alien film, heroic or villainous. Just layered, believable, messy people try to get by and avoid evisceration. That’s fundamental to making the films as affecting as they are, but it also allows them to do another really important thing…

Create a relationship with the Alien

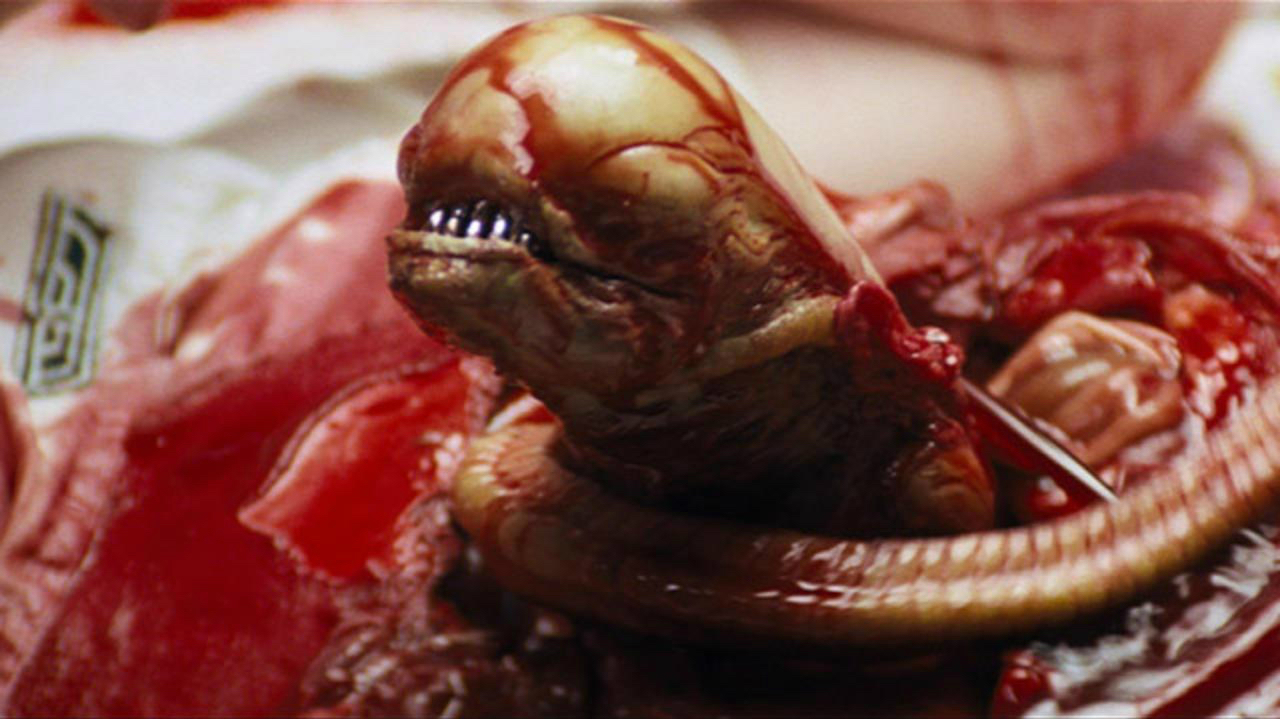

The Alien isn’t the resonant, primal force it is simply because of its fundamentally disturbing design. Obviously that’s a huge part of it, HR Giger’s oft-imitated but never replicated vision bringing innately jarring visual horror and dreamlike dread in both its form and functions. But just as important is the way that the original trilogy – and to a strangely lesser, yet more blunt degree, Resurrection – builds a real, intimate relationship between would-be victim and monster. Initially spawned by the profoundly disturbing psychosexual body-horror at the core of the Alien’s MO, over the course of the series, this implicit air of intimacy grows to a strange sense of almost symbiotic closeness that makes the Alien – whether it is immediately present or not – an impossible presence to shake off.

Starting with young, naïve Ripley’s forced, metaphorical ascension through the ranks (forged by the parallel circumstances of an increasingly dead crew and the progressive demands on her survival, the largely unseen Alien the catalyst for her self-realisation throughout) leading up to a final, quiet confrontation devoid of blood or bombast, things then move on to the fight-back in Aliens. At this point, we have a tougher, harder-edged, embattled Ripley going up against a – technically – new enemy, but the interaction is fuelled throughout by the experience of what she went through last time. Psychologically as well as logistically, one encounter begets and shapes the next.

With the subplot of Ripley’s lost daughter and the discovery of Newt blending and contrasting with the appearance of the Alien Queen (and the Alien’s inherent nature) to create multiple, intertwined explorations and subversions of motherhood, you have a seriously thematically dense film. And then Alien 3 rips everything away, and leaves a bereft and bitter Ripley to take stock of her journey, sitting at the ass-end of the universe, while dealing with the parallel of a new, similarly solitary, similarly stranded Alien. Society and its weak safety nets have gone, replaced by brutes and murderers capable of threat to protagonist and antagonist in equal measure, leading both hero and monster along a mutually fatalistic, inextricably shared path.

Of course, Covenent on its own isn’t going to be able to run the full, emotional gamut of an entire trilogy, but this kind of thought for intimacy, for a close, thematically interesting adversarial relationship is key if the Alien is going to remain the Alien, and not become just another monster. That said, Covenant also needs to balance this against the need to…

Make the Alien’s appearances count

Do not have the Alien appear too frequently. Do not have any Alien appear too frequently. We know that Engineers are going to appear in Covenant, alongside several of their bio-crafted creations, but for these creatures to maintain any sort of power, they need to be used sparingly. If they show up too much, they’ll lose all of their enigmatic weight and mystique. If their appearances are too ‘big’, too driven by action-set-pieces and gimmick visual stunts, then they’ll lose their power again, their presence diluted by the spectacle, and the surreal reality of their appearance made cartoonish and overblown. The Alien needs to remain potent as an idea first and foremost, and an idea can only hold together in the mind. Too many literal appearances and the conceptual horror becomes eroded by a literal – and less effective - replacement.

Again, the original trilogy gets this right. Xenomorphs get minimal screen-time in all three films until their respective climaxes – even in Aliens, with its apparent hundreds of hive warriors. These films understand that the notion of omnipresent Aliens is scarier than any adrenalin-rush appearance, and thus ensure that their on-screen actions are choreographed only to punctuate and strengthen that abstract idea. A swift, bloody, out-of-nowhere kill here, a brief, nightmarish piece of imagery there. That’s enough. Evoke and intermittently refresh the essence of the beast, but don’t replace that essence with concrete representation. That way you’ll…

Make sure that the Alien dominates the environment

For all the xenomorph’s scarcity in the first three films, it feels like it’s everywhere. There are several, clever reasons for that. Firstly, we always feel we know just enough about the organism to loosely define its (considerable) abilities, but not so much that we’re sure of them. We have solid enough rules to work from that the films’ events feel fair and consistent (vital in making any horror hold together satisfactorily), but we always feel there could be another nasty little secret or two hiding in the still largely unknown beasts’ repertoire. We know they’re fast, we know they can climb any surface, and we know they hide really well in dark, cramped places and kill with quick brutality. But that’s about it. That might be everything, but thanks to the Aliens’ brief, minimal appearances, we can never be too sure.

Secondly, the Alien trilogy is just typified by really, really good direction. The final reel of Alien is a masterpiece of terrifying, uncomfortable tension, but that’s not just because of the sirens, the countdown to the ship’s self-destruction, and the potential for the Alien to screw Ripley’s escape at any moment. Pay attention to the audio-visual direction of that sequence. It’s formed of horrifying ambiguity throughout, the various dangling cables, exposed pipes, and hissing steam jets of the dying Nostromo made indistinguishable from the Alien’s mysterious physicality by the persistent strobe lighting. Aliens pulls similar tricks with the detritus of collapsed, half-melted corridors, then adds the kicker of whole areas taken over by Alien matter. Alien 3’s pipe-laden, iron-cast, industrial hell then picks up the baton admirably.

In many ways, this stuff is a visual continuation of the intimacy I was talking about earlier. The concept of ‘Alien as idea’ too. The point of the Alien isn’t to simply be a scary monster. Its purpose it to invade every area of its victims’ reality, its presence infesting everything with barely knowable dread until only death – its or theirs – can break the bond. Covenant needs to get that right, and being apparently set on the Alien homeworld, it has no excuses not to.

Do not explain too much

I know this one is a nightmare of temptation. And I know the plan of Covenant and the remaining prequel films is to explain the Aliens’ origins. But I’d rather they don’t go all the way. Why? Because the unknown origin of the Alien is fundamental to its essence, and thus operates as the foundation for everything I’ve talked about above. ie. Everything that makes Alien work.

Seriously, it is. The raw power of the bizarre, deadly invasion in the first film is implicitly underpinned by the surreally grandiose mystery of that crashed, biomechanical ship. It’s one thing fighting an ambiguous, genuinely alien threat, but when said threat could be – and probably is – an offshoot of something much bigger and stranger than humanity has ever encountered, the stacking effect is confoundingly potent. Each Alien film does a great job of adding to the mythology without explaining, Aliens exploring the creatures’ life-cycle in more detail – but without touching the bigger picture – and Alien 3 establishing that the embryo’s host dictates a degree of its evolution. But none of them detract from the wider mystery that gives the Aliens that extra level of power.

It’s one thing to have ideas about what that ship was, where it was going, and why it was transporting what was in the hold. It’s another entirely to be told explicitly, whether the official answer agrees with our own perceptions or not. Even if we’re right, there’s no win to be had. The simple existence of a definitive answer at all means that we’ll lose something important.

Oh, and one last point…

For God’s sake, backlight the Alien like crazy

That’s how you film the Alien. All flickering silhouettes, ambiguous, contorting shapes, shadows, spikes, dorsal pipes, and skull-peens. This thing isn’t a Starship Troopers bug. It’s an eldritch, otherworldly, sex-nightmare space-demon. It is of the shadows. Definite it by the shadows. Shape it by the point that light and darkness meet.

More of that, less of the sunlit field business, and I’ll be a whole lot happier, thanks, Covenant.