Collected Works: Insomniac's Ted Price

Burbank-based Insomniac might never have existed were it not for Doom, which seems like a strange starting point for a studio that many know thanks to a purple dragon and a wombat-inspired alien with a tiny robot sidekick. Since its formative act of id homage, however, the studio has oscillated between the family-friendly vibe of Ratchet & Clank and Spyro, and the darker territory of the Resistance series and Fuse. But no matter how old the target audience is, every one of Insomniac’s projects has been fuelled by the studio’s constant desire to push against the limits of what can be achieved by an independent developer. Now, 20 years after founding the studio, Ted Price joins us to recall the key games and moments that have come to characterise Insomniac today.

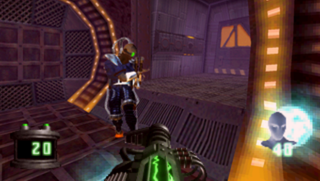

Disruptor

Publisher Universal Interactive Studios Format PlayStation Release 1996

“For me, starting Insomniac was all about – at least at first – making a game that was similar to Doom. I was a big Doom fan, and my personal intent was to create a firstperson shooter on 3DO, because it was just out and presented the first opportunity for a garage developer to fund his or her own operation, since it was a relatively cheap platform to build on. And when my partners, Al and Brian Hastings, joined me in the summer of 1994, we went full bore into developing an FPS, which became Disruptor.

When we were developing, it was really low-tech. We didn’t have any real 3D tools, so I would actually design the levels on graph paper and plot out all the points before they would be run through Brian’s tools and Al’s engine and we’d end up with 3D environments in space. That was how we built our first playable, and it was incredibly work intensive, but we were very proud of it.

At the time, we were working with Universal Interactive Studios as our publisher, and I remember driving up to Los Angeles with our first playable that we worked so hard on, and getting told, ‘This is terrible; this is not a first playable. What are you guys thinking? You better turn it around.’ And that’s when we faced our first taste of the reality of the game development business: you have to be better than you think you are to succeed.

So we went back to the drawing board and rethought how we were making games, rethought how we were putting together our levels, rethought how we were approaching design. And we got a lot of help from a guy named Mark Cerny, who stepped in and said, ‘Look, guys, if you want to make a firstperson shooter, this is how it should work.’ He helped me figure out a better way to plan, and on a design side he helped all of us figure out a better way to lay out levels and think about enemy placement and weapon strategies.

He and his colleagues brought in a really talented production designer named Catherine Hardwicke, who was famous for Tank Girl at the time, and has gone on to do a lot of big films since. I remember meeting Catherine: she walked in and she had this hat on with a bird on it. I thought it was a real bird. She’s just a real character, but she’s also incredibly skilled at working with other artists and helping shape the vision for a movie or a game. And she really helped us get off the ground with the visuals for Disruptor. So those first two years of our existence, building Disruptor, I probably learned more than I had learned in the previous ten years doing anything else.”

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Spyro the Dragon

Publisher SCE Format PlayStation Release 1998

“When we finished Disruptor, we released it to fairly good reviews, but there wasn’t really any marketing done for the game and I remember seeing it called ‘the best game that nobody’s ever heard of’ in a review [laughs]. And we realised that it was unlikely we would be able to do another Disruptor, because the audience wasn’t there. Our team had grown to five people by then, and we felt like we needed to move in a different direction. We’d all been living in this sort of dark world of Disruptor – even though it was a little bit campy, it was a fairly dark story and a dark game – and we wanted to lighten things up a little bit.

Again, Mark Cerny, our executive producer at the time, said, ‘Hey, guys, PlayStation is continuing to grow, but one area where it hasn’t been able to succeed is the family-friendly market. Nintendo has a lock on that market. What could you guys do to break in?’

And so we went into our brainstorming mode, and one of our artists said, ‘I’ve always wanted to do a game about a dragon.’ All of us glommed onto that idea and we all had different visions. I mean, some of us were thinking about a giant dragon that sets cities on fire. Others were thinking about families of dragons and more of an RPG approach. Obviously, we ended up deciding that we wanted to have one playable dragon who was a cute anthropomorphic character rather than scary, and we worked with an artist named Charles Zembillas, who started fleshing out who this guy was.

I remember working directly with Charles when he was coming up with kind of an angry version of Spyro, and we had a lot of miscommunication as we tried to figure out his personality. We continued softening Spyro from this almost scary-looking small dragon to a much more approachable one. Then it became all about colour, and it’s funny how you can have days of arguments over colour.

We went through every colour in the rainbow. We even went through multiple colours – we had rainbow Spyros – trying to figure out what the right colour was. I remember Craig Stitt was presenting all of us with different versions of Spyro and the one that really popped off the page was the one with the purple body and yellow horns and the yellow wings.

And that’s where we collectively said, ‘Yup, that’s it, let’s do it.’ Those formative moments really do stand out for me. Like when Al got the brand-new engine up and running. He had been working on this tech which could draw long distances on PlayStation 1, which was something that most games hadn’t been able to do. We put Spyro in this pastoral setting, where you could see a castle in the distance and this big hedge maze, and we had Spyro gliding over it, and it was another of those transformative moments for us.

It was a really fun game to make, because there were very few rules; we had an animator named Alain Maindron who would come up with these absolutely insane characters. I mean, one of the ones I remember in particular was this cave creature whose stomach was split down the middle and bats would fly out.

I think there were some characters that we ended up discarding on Spyro: Year Of The Dragon because we had made the move to introduce other playable characters, and we went through a lot of different iterations. The toughest one was the space monkey, Agent 9. It’s so long ago, I’m having trouble remembering, but I do recall a lot of arguments over his laser, which may not have fit with the game, but we eventually put him in. My favourite playable character was Sergeant James Byrd, the penguin who flies around and drops bombs. You’ve got this militaristic penguin dropping bombs in a game about a dragon, right? But it fits.”

Ratchet & Clank

Publisher SCE Format PS2 Release 2002

“The reason why Ratchet & Clank really stands out to me is because it was the result of an almost disastrous ending for us. We had been working on a much more mature game for PlayStation 2, and we were at the point where we had to decide whether or not we were going to move ahead with it. We’d been talking to Sony about the project, and they came to us and said, ‘Guys, we don’t think this particular concept of yours is going to work. It’s sort of in this middle ground between being adult and family-friendly – maybe you guys should go back to what you’re really good at doing,’ which at that point was platformers. I was the one who had been pushing heavily for this new game with a more mature approach, and the rest of the team thought I was nuts. So it was finally time for me to face the music and admit that I’d been wrong.

We discarded that game and went into brainstorming mode. We would have sessions where we’d get a keg and go up to the roof of our office in Burbank and try to figure out what the hell was next. That wasn’t particularly successful, but in one of our smaller brainstorming sessions Brian Hastings, our creative officer, said, ‘Let’s do a game about a little character, akin to Marvin The Martian, who has crazy weapons and moves around from planet to planet.’ And that’s when the core idea for Ratchet was born. And within a couple weeks, we had changed from Marvin The Martian to a furry character with three robot sidekicks.

The initial idea was that Clank would be three robots, all of whom would attach to different appendages on Ratchet. One would ride on his back, one would be on his arm, and one would be on his leg. It was a cool concept, because we figured we could probably combine those robots at different times in the game and make this Transformers-esque sidekick, but it became really complicated, fast. We realised that we were sort of diluting the personality opportunity for Clank, and so Clank became Clank after a few more weeks and ended up riding on Ratchet’s back in even our most early concepts.

Ratchet also went through some different concepts. At one point, he was a space lizard with a tail that would let him hang onto branches and do acrobatic moves, but that didn’t work either. We wanted to be more approachable, so that was when the furry wombat emerged. But the next step was figuring out what the hell we were going to do that wasn’t a platformer, because we wanted to move away from the collectathons that dominated the market at that point. So we went back to Brian’s original idea, which was, ‘Hey, let’s have this character use lots of different weapons.’

The very first couple of weapons we built were the Pyrocitor and the Suck Cannon, which was this big weapon that sucks things in you can use as projectiles. That gun was our first realisation that we could go a little crazy with weapons in our games. Spyro didn’t have any weapons, but Ratchet was an opportunity to take our creativity off on a new path. And with the Suck Cannon, it sort of opened up everybody’s way of thinking, too – it encouraged everybody to move away from more traditional weapons and to continue to surprise ourselves, our publisher and our fans with this kind of craziness.

After that came the Agents Of Doom, which was another fun one. I remember that emerging in the first Ratchet game distinctly. But I vividly remember Captain Qwark and his appearance in the game.

I think the first cinematic that we did for the Ratchet series was the Al’s Roboshack commercial. We wanted to come up with a way to present the story in a different way, as a sort of societal commentary. Captain Qwark’s facing off against a big Blargian Snagglebeast, then we freeze frame and then he asks, ‘Have you ever felt like you needed to upgrade your weapons?’ But then we switch over to Al’s Roboshack and you’ve got Qwark in all of his Qwark-tastic glory, with Jim Ward voicing him, doing his over-the-top delivery. And I remember seeing that and going, ‘Yes! That’s the tone! That is our sense of humour embodied in Captain Qwark.’ For me, that moment really set the tone for the entire series.

What we were doing was trying to make each other laugh, really, and have fun. And we weren’t thinking too much about whether or not gamers would find it appealing, because we’re gamers, and we figured, ‘Hey, if this is what gives us incentive to come into work every day and allows us to be creatively free, it’s probably going to have an audience.’

God, I remember so many of the weapons. I mean, the Visibomb was another of my favourites. That was a weapon nobody thought we could do in the studio, because it broke all of our technology rules within the game. We needed players to stay within a certain distance of the ground because of how we built our levels, but the Visibomb let you fly up and see the edges of the world. So we had to come up with solutions for that, but it also ended up being a real control challenge, because guiding a cruise missile – and from firstperson perspective – is a big jump when you’re used to playing a thirdperson character. So we spent a lot of time failing until it worked. But it still ended up being one of the most fun weapons, because there’s this sense of mastery that you get when you finally figure out how to control it.”

Resistance

Publisher SCE Format PS3 Release 2006

“We’d been working on Ratchet for a long time [by the time PS3 was revealed to developers], through the entire PS2 lifecycle, and we were in the process of building Deadlocked, which for us was taking Ratchet in a new direction. We were ready to move into a different genre. So when we heard about PS3, we knew that the audience was going to be a more mature one from the beginning, because early adopters tend to be the shooter fans, really. We figured, OK, maybe it’s time to go back to our original roots with a shooter and do something that’s a little bit more gritty, a little bit darker.

The first conversation I remember about Resistance was about this scene in Starship Troopers where the protagonists are in a temporary encampment and they see these swarms of creatures coming over the hills towards them. We wanted to get that same feeling across in Resistance – you’re completely outnumbered and you’re faced with this alien menace that numbers in the hundreds of thousands.

We began the game as a space opera. For six months we were trying to figure out how to make this story about time travel, lizard-like enemies and space marine-esque characters work without being derivative and we were failing miserably. It just wasn’t feeling good.

And I remember in particular, Connie Yu, our producer at Sony, coming down and checking out one of the builds that we had been making for Resistance and saying, ‘You know what, this isn’t very fun. It’d be a lot more fun if you were fighting against humans.’ I had a fairly negative reaction, going, ‘God, you know what, we worked so hard on these damn lizards. I just don’t want to remove them from the game.’ But she was right.

At the same time, we didn’t want to make a WWII shooter, because those were in vogue at the time and it seemed like every shooter had you fighting against other humans, and so we didn’t want to do that either. We were struggling. But then we began creating this story about the Chimera, this race that had seeded Earth with these giant structures that were underground and had suddenly emerged earlier than what would have been WWII, and had begun converting humans into these humanoid creatures.

When we started talking about that story, that really grabbed everybody. It was a much more grounded approach than what we had been trying before, and we wanted to present something that felt familiar but different. So the story started talking about how the emergence of the Chimera would prevent the start of WWII. That’s when the theme of the game began gaining traction. But before we even got to that point, we’d also gone down a different path where we decided that this would be a WWI game, until we realised that WWI weapons weren’t particularly compelling. So that’s when we decided to place the game in our own version of the 1950s.

I remember arguing incessantly over the very first gameplay sequence in the first Resistance, where we land you in York and you fight down the street without any health. There are no health pickups, and this is before you get your regenerative powers. I had been pushing really hard to make sure that we didn’t introduce those powers early, because I wanted to make sure that we explained why Hale suddenly has the ability to regen health. But we couldn’t do that until he was infected by the Chimera, so we had to have a part of the game where he was just a pure human. At the same time, we didn’t want to have this different health mechanic that we only give you for five or ten minutes of the game, so what ended up happening was we hit players with a sledgehammer as soon as they started, which is the total wrong way to make a game [laughs]. I thought it was easy because I’d played it 100 times, but I remember watching people after we got pretty close to the finish point and thinking, ‘Oh my God. What do we do? People are going to be so pissed at us!’ There were people pissed, but there were a lot of people who gutted it out and got to the regenerative power.”

Outernauts

Publisher EA Format PC, iOS Release 2012

“Outernauts started out as a small Facebook game but ended up being one of the largest games we’ve made in terms of the geography and number of characters in the game. It was a big, sprawling game, but most people didn’t realise it, because we used 2D art and it looked like a more traditional Facebook game. Even so, we had a lot of fans who really got into exploring the worlds that we presented in Outernauts and you could do a lot. But then when Facebook began to decline in terms of gaming popularity, we knew we had to change direction. Mobile had been exploding and we wanted to move into that field and learn more about the market and what players wanted.

So the team looked inward and asked, ‘What is it that makes Outernauts special? What can we do that will bring that same magic to the mobile audience without creating something that simply won’t work on mobile?’ And it became all about the beasts. We began going nuts with them, and one of the core elements that emerged was beast breeding, and that has become a really important mechanic for the mobile game. For us, it’s been a blast, because of the complexity of breeding: there are lots of different families of beasts, lots of different types, from common to uncommon to rare to epic to legendary. And we introduced a bunch of new mechanics that were surprising even to us: beast fusion, the crystallisation of beasts, etc. Being able to dive deep on mechanics like that in a genre that isn’t necessarily deep was fun for the team, but it was also a way for us to bring some of Insomniac’s gameplay to that audience.”

Sunset Overdrive

Publisher Microsoft Format Xbox One Release 2014

“Marcus Smith and Drew Murray came up with the concept for Sunset Overdrive at the end of Resistance 3. Drew had been the lead designer on that game, and Marcus was the creative director. They teamed up with the desire to do something different and that really spoke to Insomniac’s strengths as a studio – that wild stylisation and humour.

They presented this game that was full of tone and style to a bunch of us and we all really glommed onto it. But then at one point, we switched direction… We did this for various reasons, but it became apparent to me that Sunset Overdrive really was the game we were supposed to be making. When we came back to it, we brought our revised vision of the game up to Microsoft. Drew and Marcus made one of the most impassioned presentations I’ve ever seen, and it culminated with Drew jumping up onto a boardroom table and pretending to surf, describing one of the mechanics in the game, and it was… amazing. I think everybody’s jaws in the room dropped, because you don’t do that in a presentation! But he was sort of embodying the tone of the game.

One of my strongest memories was when traversal started working. I recall thinking, ‘There’s no way that we’re going to figure out how to make combat and grinding work,’ because as a shooter fan, and somebody who develops shooters, I’m so used to the more traditional stick to the ground, aim, fire, go to cover, right? That’s what we’re all used to, and to try to envision how you could be grinding on a wire at incredible speeds but then also accurately shooting enemies that are several meters below you didn’t make any sense. And it didn’t make sense to a lot of people on the team until [lead designer] Cameron Christian and our designers really dug in and began examining the metrics and the aiming mechanics for the game, and asking what really would make this fun? Why is it currently frustrating? Why are people throwing their controllers when they have to grind and shoot?

It took a lot of collaboration between Cameron and our gameplay programmers to figure out the magic combination. And it turned out to be a combination of speed, and pulling some tricks behind the scenes for aiming and enemy behaviour. And we started building on that with the Style system. I can’t remember who proposed it, it might have been Drew, but we needed a reason to get people grinding. It’s not enough to just say, ‘Oh, it’s fun to balance and grind from wires.’ Sure, that’s fun for a while, but at some point you need to be rewarded for it. So everyone racked their brains until the Style system was born.

As for going back to Resistance, because we’re independent and we’re IP creators, I’ve learned to say never say never. I do feel that with Sunset Overdrive, Outernauts, and Ratchet & Clank going on right now, there’s a sense of optimism for us, because we’re working on games that are seriously fun to create, games that have far fewer rules than realistic games. And as creators there’s nothing better to feel like than that you can experiment and whatever you come up with will probably fit in these crazy worlds that you’re creating.”

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.

Most Popular