An exploration of the original Assassin's Creed, an overture rooted in method acting

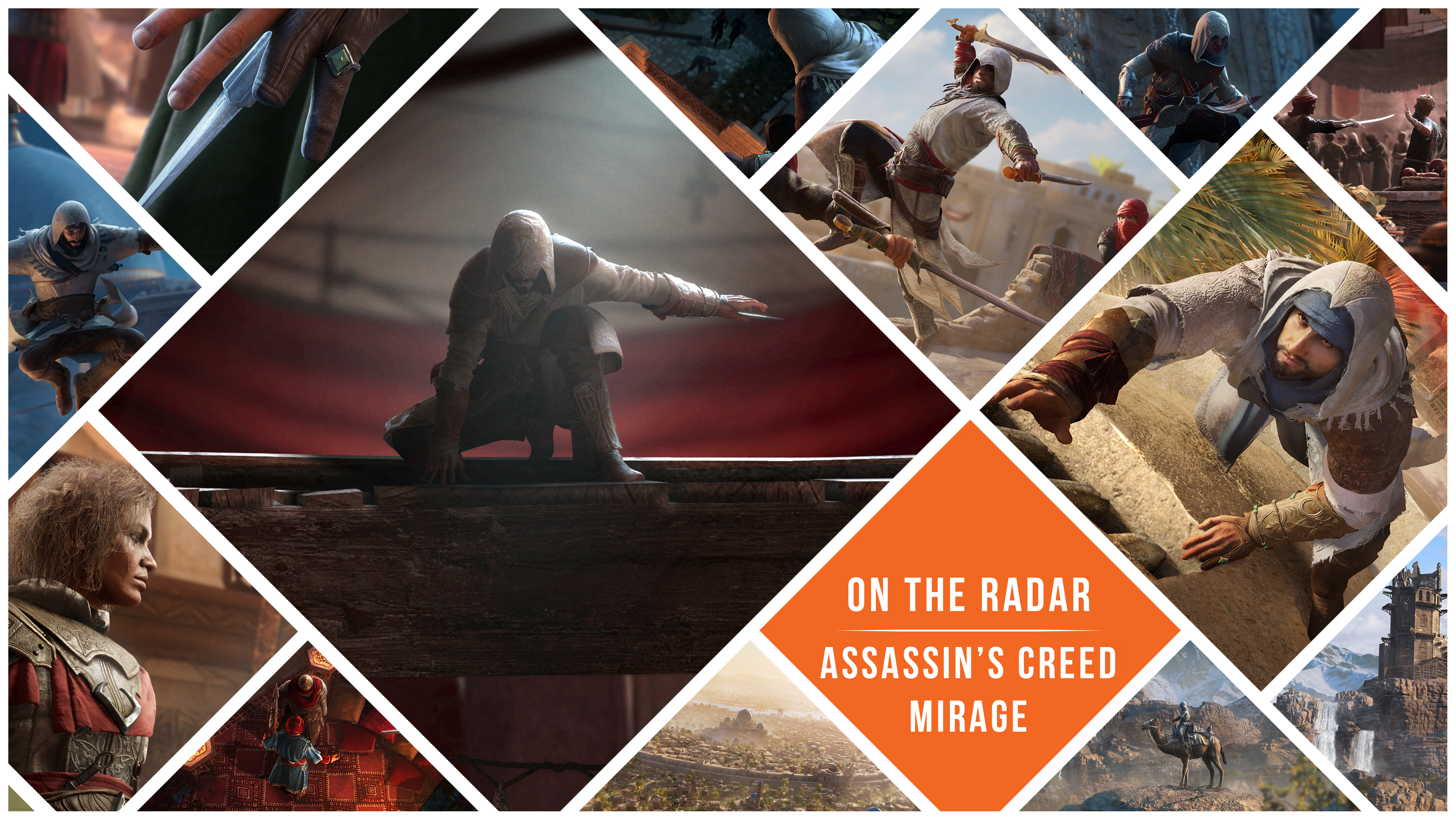

On the Radar | Remembering the game that started it all

History records, with a questionable level of accuracy, that Altaïr Ibn-La'Ahad hated the water. Poke even one of his toes into the Barada River, and the synchronisation bar that measures your commitment to recreating the events of his life drops straight to zero. The man would stick a blade into an English crusader in public, but a bracing swim in the waterways of Damascus? Far outside the bounds of possibility, academics agree.

It's fair to assume, then, that Altaïr wouldn't be fond of a naval metaphor. But 13 games into a cycle of constant iteration, the Assassin's Creed series is the quintessential Ship of Theseus. Going back now to the 2007 game that started it all, there's almost no part that hasn't been replaced in the years since. There's the occasional mannerism that's familiar: the rhythmic way the assassin shifts his weight during a climb, and his bird-like bearing on a spire. But even those with an intimate knowledge of Assassin's Creed's past decade would find themselves off-balance in Patrice Désilets' strange first experiment.

Catch me if you can

This AC1 retrospective is part of our Assassin's Creed Mirage: On the Radar coverage.

This is a supposed stealth game in which there are no tools for distraction; in which silent takedowns are finicky and escalating street fights the norm; in which you thunder into town on horseback then methodically work the alleys for information. It's contradictory, frustrating, and fails to live up to its central fantasy – but is beguilingly different to the games it birthed. By his own admission, Désilets has a tendency to reinvent the wheel. In Assassin's Creed, his first step was to redescribe it. The row of small white rectangles in the top-left corner on the screen may resemble a health bar, but they actually symbolise your tether to Altaïr's memories. Take too many hits, or dole them out to civilians, and you'll lose your connection. Not as a punishment, per se, but because that's not how the man lived. Save some innocents or clamber up a church and suddenly you're starting to resemble Altaïr as his friends knew him. Success in Assassin's Creed is an act of roleplay – even if, for the most part, it involves simply staying alive. Or avoiding water.

The four colourful face buttons of a controller, meanwhile, are reimagined as a holistic representation of the human body's extremities. Triangle handles the head, allowing you to scout for enemies or spot opportunities from a vantage point; Square and Circle are the arms, dedicated to grabbing handholds, swinging swords, and pushing guards over ledges. Cross, finally, is reserved for matters of the feet, carrying you out of trouble at top speed. It's a control scheme that reads like a discredited medieval theory of medicine, and is truly baffling for a new player. Subsequent entries managed to ditch much of this language without fundamental changes to the button mapping, which suggests Désilets' protagonist puppetry may not have been so revolutionary after all. But Assassin's Creed deserves credit for introducing a generation to contextual controls – in turn enabling more complex action games that used every button on the pad and then some, knowing that players could keep up.

This stubborn newness runs deeper still. Today, Ubisoft is known for the cross-pollination of its franchises, the autocover mechanic from one series turning up in two or three others. But Désilets' team took almost nothing from their colleagues, to the point of self-sabotage. Critically acclaimed stealth games had been developed under the same roof in Montreal, and Assassin's Creed could certainly have benefited from the brains of the guards in the Splinter Cell series, with their multiple levels of player awareness.

"Yet that learning was tossed aside. In theory, this was because Assassin's Creed was building a new paradigm based on social stealth: a ruleset in which you relied on good behaviour, rather than deep shadows, to blend into the background."

Yet that learning was tossed aside. In theory, this was because Assassin's Creed was building a new paradigm based on social stealth: a ruleset in which you relied on good behaviour, rather than deep shadows, to blend into the background. Yet in practice, your ability to meld with the foot traffic in Acre is very limited, dependent on whether there happens to be a group of white-hooded scholars passing nearby. While there are creative options for escape, such as the counterintuitive thrill of sitting calmly on a bench as your pursuers hurry by, you're often forced to rely on stripped-back versions of traditional stealth mechanics to remain undetected in the first place. And while it's possible to deal with an individual spotter before a situation escalates, your witness indicator gives little indication of which eyes are watching. A single shout from a guard typically devolves into a Jerusalem-set Benny Hill routine.

It's comforting, then, that Assassin's Creed doesn't suffer from the usual dissonance between player and character. Your cack-handed antics are matched by unconcealed contempt from your peers in the Brotherhood, who Altaïr has riled with his hotheadedness. It's a trick more action games should employ: reflecting back the self-hate of new and clumsy players, rather than surrounding them with sycophants. It feels right, novel even, to be disrespected. And when your grudging allies begin to thaw, it feels that you've earned their warmth. It's with the goal of teaching some humility that Assassin leader Al Mualim stipulates that you hunt down your targets yourself – personally handling the drudgework of piecing together the location, mindset and weaknesses of your prey. And so you step out on the town, pursuing leads and squeezing informants for intel. It's an idea that hasn't survived into Assassin's Creed's sequels, but is also one of its best.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Tuned in

This feature originally appeared in Edge Magazine. For more fantastic in-depth interviews, features, reviews, and more delivered straight to your door or device, subscribe to Edge.

Whenever an Assassin's Bureau chief begins imparting local knowledge, it's worth paying proper attention. If the man on the ground says you ought to sniff around the rich district's southernmost church, then you can save yourself much scaling of buildings elsewhere. The same approach applies once you've made contact with an informant – the closer you listen, the less likely it is you'll make a meal of the coming assassination. At their best, these briefings give you a sense of your target's state mind as well as their whereabouts. The steward of Acre can be relied upon to retreat to the back of his citadel whenever challenged by King Richard's authority – his headspace reflected in level design.

Additional investigation yields further detail, including maps of guard positions and potential entry points. Studying them is key to your preparation, and yet you'll only find them by digging in the pause menu among the stats and sound options – something the game never teaches you adequately. It's fair to assume many players never happened upon the materials they'd worked so diligently to acquire. Why would Ubisoft choose to bury such pertinent information? It's a question answered, indirectly, by Al Mualim – who wants Altaïr to become not just a soldier, but a surveyor. "Like any task, knowledge precedes action," he says. "Information learned is more valuable than information given." It's a good line, but even so: a tooltip wouldn't have hurt.

Once you've learned to commit those maps to memory, the assassinations themselves take on new weight, becoming exams you've practised for. Successfully creeping up on your target without alerting their bodyguards is a source of pride and relief. Especially since the game regularly seeks to undermine you with scripted chases and cinematics. This is no murder sandbox, sadly, and the existence of the recent Hitman trilogy certainly doesn't flatter it. Even outside the investigation phase, however, Assassin's Creed is admirably dedicated to procedure. The ritual night's rest before the kill; the gifting of a feather from the chief of the local Assassin's Bureau, which Altaïr paints with blood once the deed is done; the return to Al Mualim in Masyaf; and finally, the horseback ride out to your next destination. As gameplay loops go, it's rather a large one, justifying the accusations of repetition. Rarely has a triple-A game gone to such lengths to place you inside the costume of an action hero, during downtime as well as in the set-piece moments of their life. The result, to borrow Abstergo terminology, is better synchronisation between player and protagonist.

"Lessons from the Splinter Cell and Far Cry series were folded in over time, and by 2014's Unity you could just about blend with the crowd and pass completely unknown in the city".

It's just a shame that so many parts of that loop fail to support the game's supposed main themes. Only a fraction of your investigation time is spent spying or pickpocketing, activities that employ social stealth. Instead, many informants require you to break cover, scrapping in the street or, in the most demeaning cases, collecting flags from nearby rooftops before they'll talk. "Have you forgotten the meaning of subtlety?" Jerusalem bureau head Malik asks during a typically heated exchange. It would be a prompt to reconsider your approach – if only you had the tools to do so.

Those tools did come, eventually. Assassin's Creed was a smash hit, giving its developers time to fill the gaps in its mechanics – to make its structure less strange, for better and for worse. Lessons from the Splinter Cell and Far Cry series were folded in over time, and by 2014's Unity you could just about blend with the crowd and pass completely unknown in the city, the way the fiction of the assassins had always suggested they could. The series has played host to a variety of genres since: wilderness survival, pirate fantasy, Witcher-style RPG. Yet it still has a distinct ruleset of its own, and that's down to the bloody-minded determination of Désilets and his team to lay down new flooring, granting Assassin's Creed an essential oddness that, even as all the original parts have been replaced, can never quite be finessed away.

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more fantastic features, you can subscribe to Edge right here or pick up a single issue today.

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.