Angel at 20: Why it's time to give the surprisingly feminist Buffy spin-off another chance

Where Buffy deals with friendship and adolescence, Angel tackles racism, sexism, homelessness, and assault

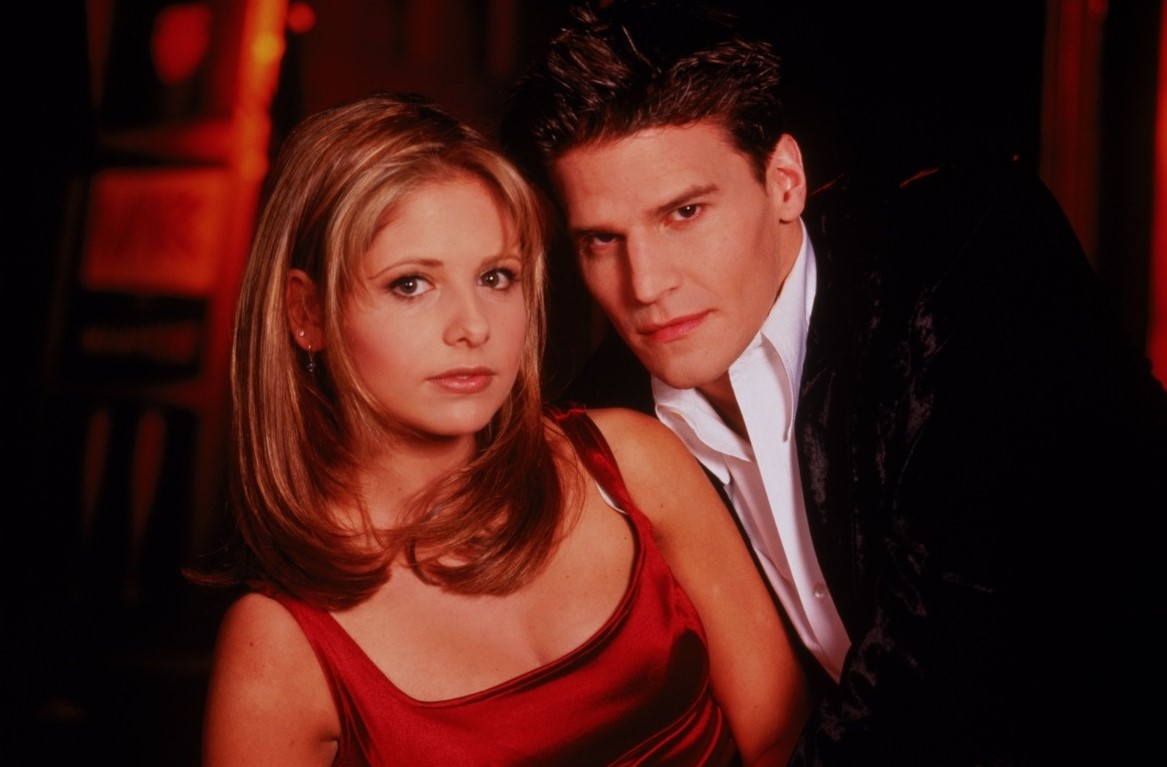

Like many Buffy the Vampire Slayer fans, I watched Angel simply because it offered a fresh vein of Buffy-related content to suck up. Considering Angel's brooding presence in the main series, the spin-off series – which focused on the eponymous vampire-with-a-soul’s life and redemption mission in LA – promised doom and gloom. As a result, I came to it preemptively exasperated, as did many other fans, some of whom abandoned the series feeling that way.

And it's easy to understand why. On a surface level, Angel seems to be missing some key things that made Buffy so beloved, least of all Buffy herself. The humour and the female energy of Buffy were exchanged for grit, and some fans were not particularly keen on watching Angel mope and self-flagellate in perpetuity.

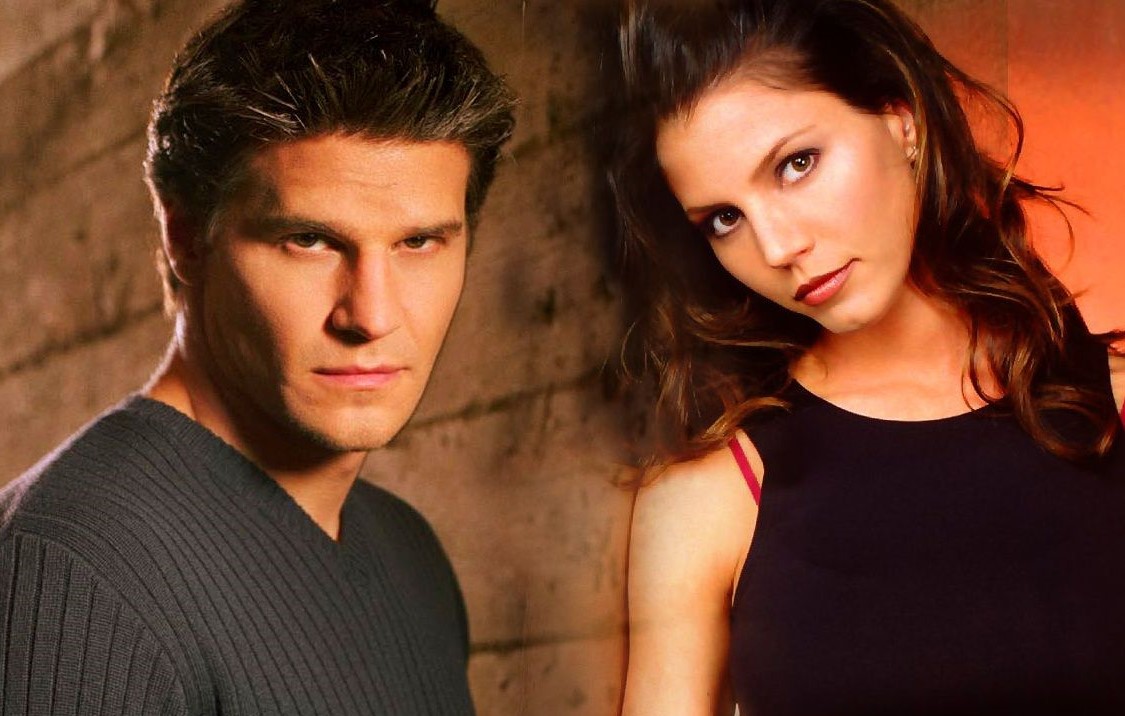

Yet, Angel, which turns 20 on October 5, is not that. For a start, the series is fully self-aware of its leading anti-hero’s ridiculousness. The characters around him – firstly an Irishman called Doyle, soon Cordelia Chase and Wesley from Buffy, plus newcomers Gunn and Fred – all comment on his brooding tendencies. Angel soon finds its feet with its core five, and, in later seasons, is as funny and as genuinely heartbreaking as Buffy ever was, if... different.

Sucker for a spin-off

Buffy, which ran from 1997 to 2003, remains in the cultural zeitgeist for numerous reasons, thanks partly to its perceived feminism. The series not only featured a fantasticly realised female lead, but it dealt explicitly with themes like assault (as in Spike/Buffy), consent (Xander and his love spell), and autonomy (Buffy’s entire predetermined destiny). It seemed unlikely that Angel would find room to be about anything more than Angel’s ego. Yet, with the same creative team on board, Angel managed to be in many ways even more human than its slayer-centric counterpart.

In its earliest episodes, Angel’s purpose is to save the women of LA. That’s not necessarily new for him, but Angel shows us real women in relatable trouble, at risk of stalkers, abusers and rapists. In the first episode, “City Of”, Angel attempts to save a woman who’s being stalked by a rich man, only to fail – she dies, and he feels he has to avenge her death. In “I Fall to Pieces”, a woman is again being stalked by a man she went on one date with.

In “Untouched”, a woman with Carrie-esque powers is cornered by a group of potential rapists sent by Wolfram & Hart. She offers to have sex with Angel in exchange for protection, echoing ideas instilled in her by her abusive father. Most of the men attacking women turn out to be demonic in some way, but Angel is monsterising our rational fears. In our world, demons don’t exist – but men do.

These themes come up a lot in Angel – Cordelia, especially, sees her boundaries violated over and over again. She is inseminated with demon spawn and made pregnant overnight by a (human) one night stand, leaving her shaken as many women often are the morning after. A group of demons also use Cordelia’s head as a host for their spawn; she has visions forced on her by a male colleague via a kiss; her body and mind are brutalised by physical manifestations of the visions by Wolfram & Hart; the vampire of the first episode kidnaps and intends to kill her. Issues of consent come up frequently for Cordelia, and, sadly, actress Charisma Carpenter’s story echoed that, as she was pushed off the show before season 5 began after becoming pregnant.

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

It isn’t just women – while Buffy is about saving the people of fictional Sunnydale from the evils that come from the Hellmouth, Angel focuses on LA itself. The detective agency Angel Investigations save anyone who’s vulnerable to the perils of the street or to being taken advantage of. In “In the Dark”, a tortured vampire who is obsessed with children takes them to a pier – and the gang rush in to save them. In “Eternity”, an actress begs Angel to turn her into a vampire so she can be young forever after he saves her from a stalker. In “Blood Money”, Angel meets Anne, a former runaway and Buffy character who runs a shelter for teens.

Gunn, a friend of Anne’s and member of the group, is a black runaway and demon hunter who wrestles with his old crew and new identity throughout the show. One episode sees his friends and the kids at the shelter fighting with renegade zombie cops who are hellbent on committing violence against them – Gunn says that the cops will come for him because he’ll be “walking while black”. The story might be told through a lens of mythology, but it’s a familiar one. Angel doesn’t shy away from topics that exist in the real city it’s set in – it embraces them, commingling demon issues and humanity. Angel doesn’t distort or minimise human issues, even in the face of apocalypse.

In Buffy, demons are, other than a select few, enemies to be slaughtered. That’s the case in Angel, initially, too, but as the series goes on it’s revealed that there are shades of grey. LA has demons living as people do – watching TV, running nightclubs, going to work. Angel protects them, too. We learn that things are complicated; that demons have humanity and humans can be evil. The Big Bad of Angel isn’t a demon but a law firm mostly run by humans that helps both evil people and evil demons to get away scot-free.

Angel is a vampire with a soul cursed to walk the earth atoning for his years of sins for all eternity. LA is the place where he gets to do that, constantly reconciling the things that he has done. But the show, and LA, also function as a space for other characters to find redemption. Cordelia, humbled after a failed acting career and her parents’ financial mistakes, must atone for being a bit of a bitch. The men wrestle with what they are capable of doing to women – Wesley for his failures as Faith’s watcher, Gunn for killing his sister after she turned into a vampire.

In season 3’s “Billy”, a man who can force misogyny to surface in other men turns Wesley and Gunn against Fred, resulting in Wes beating himself up for eternally. Not one of our champions is perfect, but they strive to be better humans. They form a gang of misfits, proving an idea that comes up in Angel over and over – everyone belongs in LA (and Angel) because no one does. Buffy characters come and go, seeking their redemption, too: Faith, Harmony, Darla, and Spike all swing by to be saved.

That isn’t to say, of course, that the women of Angel are perfect. Lilah Morgan, the evil lawyer who the gang come up against time and time again, is shown to be more complex, swinging back and forth between good and evil long after she’s dead. Cordelia has an evil spell, too, and even sweet Fred gets to have a vicious side when a man infects her with an illness and uses her as a host for the ancient demon he worships. Her death is in service of a man’s ego, and she becomes the vicious Illyria, who gets a redemption arc all her own, too, after calming down a little.

Angel isn’t necessarily more human than Buffy, but it does give more time to real, human stories than we might expect. Where Buffy deals more with friendship, adolescence and Buffy’s own struggle as both teen and slayer, Angel’s demons are male ego, rich people, and members of authority. Its foes are the same issues that real people in LA deal with – racism, sexism, homelessness, assault. It explains these stories through the lens of demons and mythology, sure, but they’re recognisable stories. On its 20th birthday, give Angel a chance – you might just be as surprised as I was.

Want more Buffy? Check out our ranking of the best Buffy the Vampire Slayer episodes

Marianne Eloise works as a freelance journalist covering film, TV, wellness, digital culture, money, and music, and a variety of other topics. You'll find her bylines in a variety of print and online publications, such as GamesRadar+, The Cut, The New York Times, Vulture, i-D, and Dazed.