It’s the urtext of science fiction. The Rosetta stone. The book responsible for the genre’s vocabulary – establishing its themes, announcing its promise. Tales of speculative fiction were told before Frankenstein (AKA Frankenstein: Or, the Modern Prometheus), which was first published over 200 years ago, on 1 January 1818, but it was author Mary Shelley who launched SF as a viable means of mainstream storytelling.

Before HG Wells wrote of Martians invading Earth, before Jules Verne made Captain Nemo the scourge of the planet’s oceans, a teenage girl conceived of a man, Victor Frankenstein, who tried to create life, but instead birthed a monster.

Shelley’s story began in June of 1816, when she and her husband, the Romantic poet Percy Shelley, challenged each other and their friends Lord Byron and Doctor John Polidori to frighten each other with original ghost stories over the course of three days at Villa Diodati, Byron’s mansion in Switzerland. Shelley’s life had been one plagued by death.

Her mother, the feminist pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft, had died when she was just two weeks old, and the 18-year-old had been devastated by the recent loss of her infant son. The tale she told was of someone who sought to conquer death.

Playing god

Speaking with our sister publication SFX magazine, Dr Sorcha Ní Fhlainn – a senior Lecturer in film studies and a founding member of the Manchester centre for Gothic studies at the city’s Metropolitan university – explains the forces that were at work in Shelley’s mind...

“The idea of death and reanimation and the creation of something that could be monstrous but is not fully capable of living – in so far as it’s a stillbirth – that was a huge issue for her. Her maternal pangs, if you will. This is something that she ties into Frankenstein.

"Because the will to make something live doesn’t mean that it should. That’s something that Frankenstein grapples with. Particularly when he beholds his creation and he discovers that he’s not willing to take responsibility for what he has done, and for what the actual giving of life entails. The pitfalls of it. That biographical element informs the psychological drive behind that story.

Sign up to the SFX Newsletter

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

“Mary was also interested in the idea of galvanising life. So the alchemical origins of how to ring things to life that were non-living, that’s something that fascinated her from a scientific and philosophical perspective. Considering her father was [the political philosopher] William Godwin, that makes sense that she would have those kinds of inquiries and those fascinations with science and the limits of life, and the theological and philosophical elements of that.

"What’s really interesting about the creature,” adds the scholar, “is that by making him a creation outside of God or outside of the natural order, even though his body parts are selected to be beautiful when they’re stitched together and brought to life they’re made hideous. So already the idea of making him something that can be falsely beautiful, when that’s brought to life it’s something horrific.

"It’s something that is absolutely against what is natural and normal. so even his body is a collection of bits that don’t really work in terms of natural creation. You see the hodgepodge, and you see that all the bits work and all the bits can be put together, but when they’re put together it’s actually hideous. It’s incapable of being alive.”

Three separate editions of the novel were published in Shelley’s lifetime. Although the original 1818 edition was published anonymously, the author’s name was added in 1822 (the year of Percy’s death). In 1831, Shelley published a revised edition.

“The definitive version is the 1818 edition,” says Ní Fhlainn, “because it is as she realised it. I think she was lacking in confidence as a writer, even though you wouldn’t find that on the page. But she was feeling that she was in the shadow of her mother, her father. They were the literary/creative stock from which she came. She was surrounded by Shelley and Byron and Polidori. She was in great company, but she was in company that was determined to shape the future. So there was ambition most certainly in that group. Hence why you have that line that Victor gives to Walton, 'Beware ambition'.

"This is something that can lead to great hubris... Yes, the 1818 edition is the one that scholars tend to return to. In terms of the differences between them, there’s a little bit of polish and rewrite, but the guts of the story are absolutely the same.”

Scream queen

While two theatrical adaptations of the novel were produced before Shelley passed away in 1851, the 20th century saw numerous films inspired by her masterwork, each one appropriating it for their era – starting with Edison Studios’ loose 1910 adaptation, directed by J Searle Dawley and starring Charles Ogle as the monster.

“Edison’s certainly is the face of psychoanalysis. The face of your doubled self, and the monstrosity you’re capable of. You need to be domesticated and saved by the power of marriage and being bound to a woman. Your terrible deeds are now being controlled because you’re domesticated.

“Because you’re going to not give into that dark half of yourself... if you watch the film, you see that it’s very much using that kind of doubled imagery. You see the creature destroyed, because you see his reflection is caught in a mirror and he’s able to be overcome that way.”

The most iconic screen adaptation of Shelley’s novel remains Universal’s 1931 Frankenstein, featuring an uncredited Boris Karloff as the creature. Directed by a gay Englishman, James Whale, it focuses on society’s frequent disdain for the other.

“What’s interesting about that is that the line that’s so central to the core pieces of the novel, the line ‘It’s alive! Now I know what it feels like to be God!’ – Colin Clive’s line – was originally censored. Because it’s too outrageous. It was anathema to the censorship board that you would claim anything to be ungodly in that capacity, and that there’s no sort of regret for that... Boris Karloff’s creature, he represents the idea of the creature being misunderstood.

"Whale really softens the image of the creature to make it palatable on screen. Also, I think that Whale sympathised with the monster. Shelley doesn’t really sympathise with the monster the same way.

"She makes him out to be clever, but hideous and rejected and bitter. Karloff doesn’t even get the opportunity to be all those things especially once he drowns little Maria. Then we have that culmination of anxiety with the townspeople going out to hound him at the end."

"Blade Runner’s really close to Frankenstein. Edward Scissorhands is a gentle version of it. There’s even Frankenhooker."

Dr Sorcha Ní Fhlainn

“Later Frankenstein’s,” explains Ní Fhlainn, “tend to get adapted out as many creature features do… 1957’s The Curse of Frankenstein is a really good Hammer film. That one definitely takes on the Hammer tropes. Hammer always reduces these gothic stories into almost household plays or dramas.

"Then in the ’70s you get Young Frankenstein, which is a classic, and Blackenstein, a Blaxploitation version of Frankenstein. The one I really like, and it’s really different, is Flesh for Frankenstein, produced by Andy Warhol. I like that one because it kind of does what other films are afraid to do. It makes it all meaty and sticky. That’s kind of getting back to what Shelley was doing. It shows the stitching and the goo and that there’s a bitterness to this end.

“There’s a couple of versions in the ’80s where it goes away from the Frankenstein parable, but you still have it. Blade Runner’s really close to Frankenstein. Edward Scissorhands is a gentle version of it. There’s even Frankenhooker. There’s loads of them. It’s even in American Horror Story.

"A couple of seasons ago they had a Frankenstein character. She was sewn together and brought back to life. So it depends on the film and depends on the genre, but you do see that it gets modified quite significantly across the 20th century.”

As for why Shelley’s novel has endured so many retellings over two centuries, Ní Fhlainn tells us, “It’s the celebrated beginning of science fiction. So far as the idea of that collision between science and the natural world and the transgression that produces; in terms of usurping God and usurping a woman’s place in reproduction. It challenges a lot of thinking. You’re removing the theological from the idea of creating life. It becomes that really important outpost for science having this ability to create and to bring about wonders. But what are the price of those wonders?"

“That’s the big question behind the novel. that’s something that you always come into contact with when you’re talking about science fiction, especially with HG Wells or Jules Verne. You have all these issues around — ‘At what cost, at what price, am I actually paying for this miracle I found, this wonder I have discovered?’ And you get that a lot across the later 19th century. Mary Shelley’s really that beacon, that outpost, at the beginning of the 19th century.”

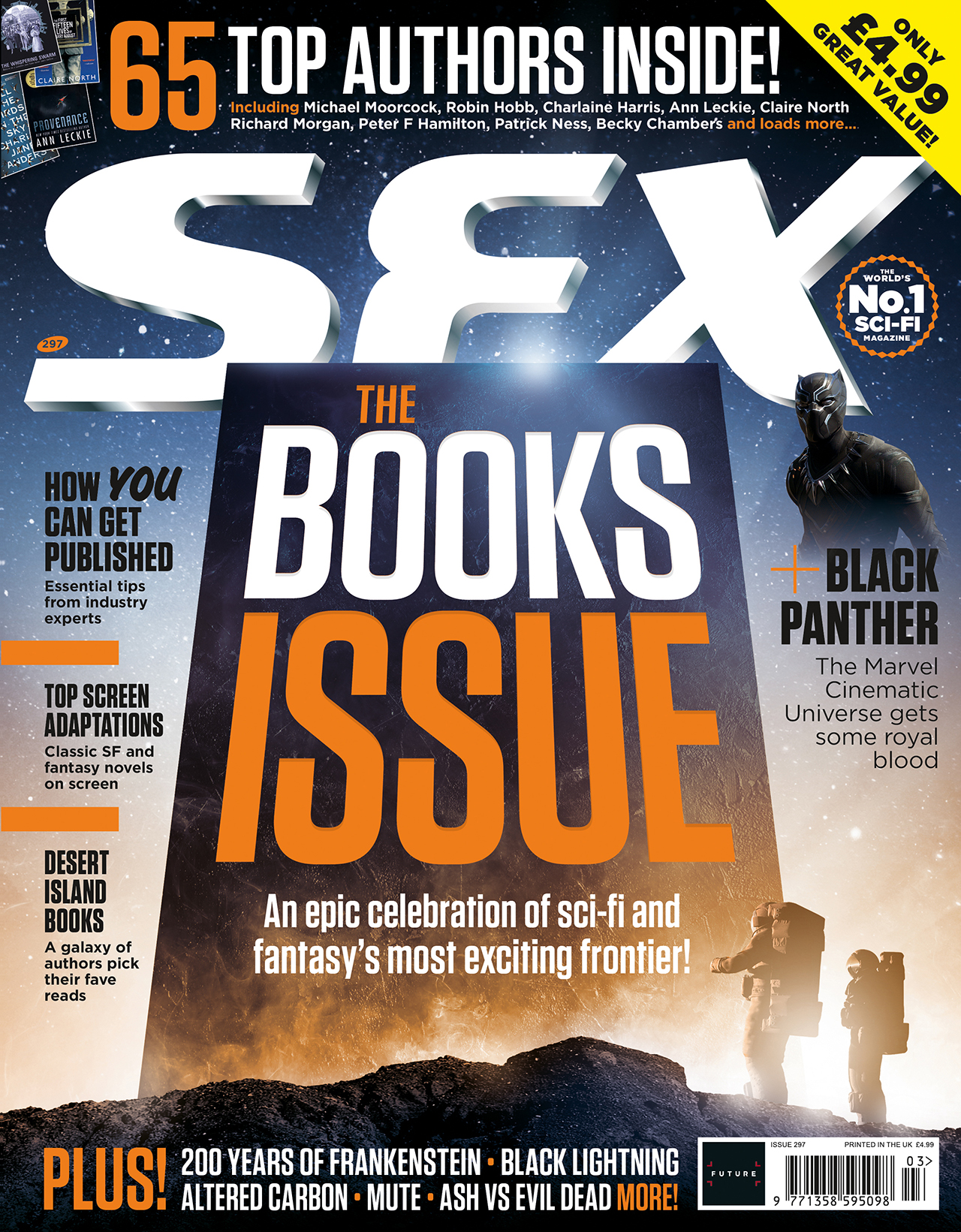

This feature originally appeared in our sister publication SFX magazine, issue 297. Pick up the latest edition - a SF and fantasy Book Special - now or subscribe so you never miss an issue.

SFX Magazine is the world's number one sci-fi, fantasy, and horror magazine published by Future PLC. Established in 1995, SFX Magazine prides itself on writing for its fans, welcoming geeks, collectors, and aficionados into its readership for over 25 years. Covering films, TV shows, books, comics, games, merch, and more, SFX Magazine is published every month. If you love it, chances are we do too and you'll find it in SFX.