P.T. is still the purest horror game around, and one of the smartest on PS4

Note: A version of this article was originally posted in August 2014, but given that it's Halloween, we thought it wise to reiterate its points. Because they're all still true.

A couple of days ago, I finally played P.T., the playable teaser for Hideo Kojima and Guillermo Del Toro’s in-production (Update note: Now tragically cancelled) Silent Hills. Weirdly, I’d had a nightmare about playing it a few days earlier. Blame the post-Gamescom sleep-drought, blame everyone I know telling me it was beyond scary. But whatever the reason, I’d had a really stern, really screwed-up dream about my subconscious’ imagined version of the game. It lingered for a while, as these things do, via that heavy cloud of mental strangeness that sticks around the morning after a heavy one. But eventually it went away.

And then, it was replaced by the real thing. You see, it turned out that the dream had been not just a weird little fore-shock, but a prophetic experience. Because P.T., while superficially very different to the weird, abstract cavalcade of gravity-bending skin-flaying I had dreamt, delivered on exactly the same impossible levels. It was a game-changer. Everything in horror gaming was different after experiencing just its first half hour. And it still is. In fact P.T. has changed my whole scale for what a good horror game is, not just in quality, but in ethos and philosophy too.

I’m a life-long horror fan. From my initial primary school vampire-obsession, to my discovery of gleeful, garish ‘80s horror, to my later love of smart, atmospheric horror literature and the increasingly harsh, meaningful sphere of the modern leftfield, I live and breathe this stuff in all its forms. So obviously I love horror games. But for years, there’s been a stark disparity in the treatment of horror between interactive computer-scares and those in other media. It’s a disparity I’ve conveniently ignored. But after P.T., I can’t any longer. You see, most horror games are games first and foremost, with the horrific elements simply sitting alongside as an aesthetic and tonal garnish. Real horror though, works the other way around. The horror is its the focus, and it makes its medium work to serve that, with real purpose.

But P.T. though. Good Lord, P.T.... Knowing that it’s a short game, I set aside an ample number of hours to start and finish it on Monday night. I only lasted 30 minutes. The reason? It was just too much. I’m not just talking about its scares, which are some of the most powerful and genuine I’ve ever experienced in a game. As much as those, it was the sheer level of directorial and artistic ambition that overwhelmed me. P.T. operates on a holistic creative level that’s been absent from horror games for so long that I just wasn’t prepared for its approach to horror in an interactive form.

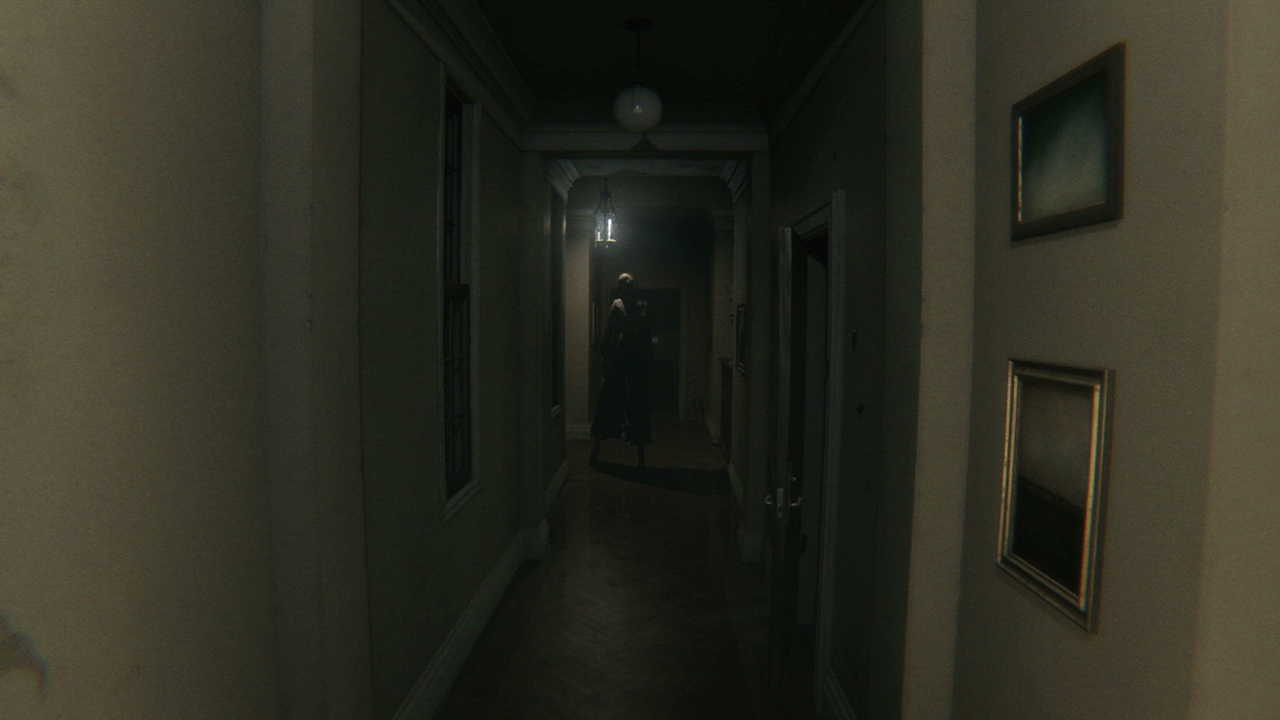

Everything about P.T. is intricately considered and seamlessly integrated. Firstly its structure. That single, looping corridor is the conduit for everything that it builds. An enclosed, fecund petri dish for intensive, intelligent, increasingly meaningful horror whose claustrophobic sense of isolation builds increasing, ambient panic. Just as its repeating, rhythmically iterating structure focuses the senses on each and every change in scenario and atmosphere, making even the smallest difference alien, significant, and desperately ominous. Every time you leave is a monumental relief, and every simultaneous instance of returning is a moment of primal foreboding at how things might, and almost certainly will, escalate, compounded by the knowledge of the seemingly countless iterations before.

It fills that structure with an unbroken feedback loop of ‘total horror’. Everything that happens, everything you see, everything you do, everything you discover, is bound through the intended experience. Everything is of the experience. Nothing is tangential or tertiary, Everything has meaning beyond simply scaring you, but the complete symbiosis of all of the experience’s elements means that it will scare you constantly.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Because P.T. understands that to evoke real horror, one must work within the realm of psychology. Externalised threats - monsters, zombies and the like - are all well and good, but they’re transient fears. Kill them, distract them, hide from them, and they’re gone. Psychological fear and trauma however, never go away. They exist inside the player and the lead character, and follow them everywhere they go, growing stronger and more potent with every new experience.

That’s the field in which P.T. plays. It operates on dream logic. Or rather, nightmare logic. Some have criticised the game for its linearity, for its obtuse, prescriptive puzzles, seeing these as evidence of lacking game design. In truth, these traits make P.T. more successful, not less. Because this is horror, not a game dressed up as horror. The ability to choose a tactical approach to a monster, to hide from it or stealth-kill it, is actually an avoidance of its real horrific substance. The potential any horror threat may hold--not that most in games really represent anything meaningful--is deftly dodged with each and every act of savvy player agency. Most games are about evading or repeatedly vanquishing horror, not dealing with it.

P.T. does not let you do that. It does not even present it as a possibility. P.T. forces you, as your sole means of progression, to face and embrace its holistic terrors, your only mechanic of interaction being closer investigation. No defence. No form of attack. Just the means to confront your fears, immerse yourself in them, and try to come to understand them. That, again, is what real horror is about.

So again, psychology is the only way P.T. could have taken things. Exploration in P.T. is as much mental and emotional as it is physical and environmental, even with the enclosed scenario notwithstanding. Puzzles make no sense if you try to approach them from a perspective of mechanical video game logic - this in itself a powerful means of disempowering you, stripping you right down, removing what you know, and forcing you approach its horrors honest and functionally naked - but when you resign yourself to living inside its nightmare, to understanding and navigating it on an instinctive level, following its rules and exploring the thoughts and ideas it wants you to, that’s when you start making progress.

The scrawled phrase ‘Gouge it out’, which prompts you to disfigure a photograph, but which also confirms uneasy suspicions about the scenario’s backstory, blending hideously with the information on the radio, the dirty, ambiguously medical vibe of the bathroom, and the thing in the sink. The phone puzzle - and the related message on the wall - establish an even uneasier sense of isolation, the frenzied symbolism of strained communication compounding the player’s situation, imbuing it with a fatalistic escalation through its slow, back-and-forth solution.

The eyeball corridor initially seems to provide a break from the slow-and-steady, restrictive movement that so suffocates from the game’s start. But again, it’s about something more. The manic, forced sprinting plays off earlier experiences of what horrors can be found by turning around corners too quickly, while the swirling, ocular painting themselves do even more. Their frenzied whirling initially compounds the dizzying panic of speed, but after repeated, potentially infinite loops of the corridor, the detail of their message can be seen.

Some eyes move faster than others. Some barely move at all. Others seem almost asleep. The message here is that while the instinct may be to tear through these horrors, and onto escape, as quickly as possible, only by stopping, standing, observing, and really seeing the devastation at the core of this nightmare, can real progress be made. And both the discovery and execution of this particular solution absolutely rely on that thinking and theme.

One last point on P.T.’s ‘puzzles’. Particularly a point about its last one. Now slightly notorious for its technically unsolved nature, the utterly abstract, unguided climactic task has been completed, but never really understood. There are various, wildly different methods of escape floating around the internet, all effective to varying degrees, and all with their own impassioned, fevered, spiralling logic to back them up. Again, some see this as a failing, But in truth, it is perfect. It's flawless. It's the point. By bringing its players to this obsessed, skewed, pseudo-schizophrenic mental state, P.T. has utterly succeeded in drawing them inextricably into full immersion in its psychological world of horror.

And the real kicker? By spreading out into the real world, by forcing solutions by way of hearsay, internet whispers, and desperate, rumoured logic, it has become its own urban myth. P.T. has taken on life, its horror story becoming real folklore, and its essence now effectively ‘haunting’ the real world.

If that’s not real, powerful horror - and if that’s not real Silent Hill - then I don’t know what is. However different it may be structurally or mechanically, if Silent Hills is taking P.T. as its philosophical statement of intent, I couldn’t be more excited. And terrified. In fact I don’t even know how I feel. It’s all too much.

(Update note: Obviously Silent Hills will be doing no such thing, nor much of anything now. But cross everything that the just-about still in production tribute game, Allison Road, can pick up the torch. If indeed it doesn't get stalled again itself)