With the Avengers getting too big for cinema, TV is a much better fit for comic books

I watched Avengers: Age of Ultron again the other night. And again, I had a great time with it. Yes, it was easier to spot the film’s flaws the second time around, free as I was from the slightly boozy excitement of opening weekend, and with my vision unclouded by either choppy 3D frame-rate or murky 3D murk. A crap CG Thor here, and illogical, narratively out-of-step-with-his-character-arc sulk from the Hulk there… But overall, I had a damn fine time, despite such moderately awkward revelations.

I did however, notice a different kind of flaw, one I’d been ambiently aware of before, but had similarly glossed over. One which exhibited itself in a slightly more subtle way than the above, but has potentially wider-reaching repercussions for a cinematic Marvel universe that continues to expand on a similar sort of scale to the actual universe itself.

You see, Age of Ultron has some undeniable pacing issues. Although consistently fun, the film gets a tad flabby during its middle act (or acts), with the titular villain’s presence, purpose, and vaguely conveyed plan rather absent from the motivational cogs of the plot. But the thing is, that doesn’t mean that there isn’t a lot of stuff going on in AoU. There’s actually a hell of a lot of stuff going on. But much of it is there for reasons other than servicing the Avengers’ second group outing. Much of it is there because in Age of Ultron, we hit an awkward logistical crossroads in Marvel’s long-term, interconnected narrative plan, leaving Joss Whedon forced to squeeze in a lot more than just a film about the Avengers fighting a malicious AI.

Age of Ultron has to be that, of course, but it also has to be the set-up for Civil War. And provide further set-up for the two Infinity War movies. And set up Thor: Ragnarok. And carry on mopping up stuff from The Winter Soldier. And tease Black Panther. Frankly it’s a miracle it exists in any decent form at all, such is the combination of unicycle stunt-riding, plate-spinning and juggling Whedon was charged with in its creation.

It was all so much simpler in the early days of Marvel’s movie renaissance. We’d get a decent single-character move, a fun credits-sting teaser for the next one, and then we’d wait a year until another character turned up on our screens to repeat the pattern. But now, much like in comics themselves, things are getting bigger, more complex, and more than a tad unwieldy, and it’s all starting to show up the limitations of cinema as a vessel for Marvel’s (rather applause-worthy) cross-media ambitions. The fact is, even with multiple films telling multiple story threads at a time, a two to three-hour story dump every 12 months or so just is not big enough to do this stuff justice any more. Marvel is – with great flair – transposing the long-established, cross-brand storytelling of comic books over to its cinematic output, but although on paper that’s a fantastic – and so far very successful – innovation, the strain in adapting to a radically different medium is now starting to show.

Have you noticed how, increasingly, cinematic Marvel heroes and villains speak almost exclusively in quips and one-liners? That’s not just because everyone loves Iron Man, and Robert Downey Jr. is really good at that sort of thing. Nor is it (just) to make the films ultra-quotable, and therefore prime for easily spread cultural resonance. It is about all of that stuff, true, but it’s also the product of having to cram so much narrative history and mechanical donkeywork into what effectively amounts to one episode a year of a really high-budget, ongoing story. Simply, there just isn’t time for lengthy, slow-burn character development.

Instead, you need smartly economical writing, with as much character packed into as few words as possible. And you can divide the page space by six when you’re dealing with a big cross-over movie like The Avengers. Hawkeye makes a warmly self-deprecating comment: character hierarchy re-established. Move on. Natasha hits him with an affectionate put-down: friendship re-established. Move on. Tony says something wittily sarcastic: Iron Man’s arrogant capability established. Move on. Cap makes a stoic, profound statement while ripping a log in half for emphasis: bigger themes of the film quickly locked in. Mov… you get it. It works, of course. Marvel’s writers are good, its casting largely excellent, and, particularly in its more action-driven, landmark films, things whip along fast enough for the broad strokes approach to work just fine.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

But the fact remains that we’re increasingly getting a snapshot version of these characters and stories, and if we extrapolate the state of Age of Ultron into Marvel’s upcoming, medium-to-long-term strategy, that phenomenon is only going to increase in prevalence. Because the reason Ultron in particular stumbles in terms of its pacing is that, more than any other film in the Marvel canon to date, it has landed at a time when there’s just a ridiculous amount of stuff going on in the wider universe, and it has to accommodate. And this is just the set-up stage. Given what’s coming over the next few years, the situation will only be exacerbated. Hell, I haven’t even touched on the new set of ripples that will be set off when Spider-Man arrives, in the middle of Civil War.

But now look at Daredevil, Netflix’s splendidly gritty, darkly character-driven adaptation of Marvel’s vision-impared vigilante. It lacks the barnstorming CG spectacle of the movies, and never once reaches for the same heights of air-punching, apocalyptic excitement, but doesn’t it get under your skin a whole lot deeper? Doesn’t it leave you with a much greater sense of having truly experienced something, rather than simply having witnessed it? Of having got to know some new characters and gone on a long, meaningful journey with them, rather than just seen some people do some stuff, and gained a general grasp of their respective senses of humour?

Now imagine the plot of Daredevil’s first season made as a movie. It could be done. In fact, the character and story arcs of season one are pretty much exactly what would be in a cinematic Daredevil reboot. But on the big screen, spread over three hours rather than 13, it would be a very different beast indeed. More focus on Matt. Much less team dynamic. Wesley as little more than an enigmatic henchman. A couple of regretful lines from Fisk, but nothing to compare to the immensely affecting, painfully nuanced portrayal we get from Vincent D’Onofrio. A fair few more of the supporting cast missing entirely, along with the sheer, emotional heft of the season's final episodes.

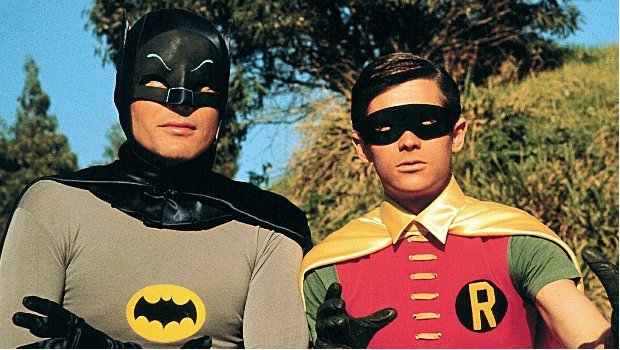

It used to be that TV superheroes were the bargain basement version. Between the (brilliant, knowing) goofiness of Adam West’s Batman, and the likeable naffness of Dean Cain’s Superman – not to mention the seething, over-earnest horror of Smallville – for a long time it seemed that TV comic book adaptations were never going to grow into anything satisfying or mature.

If they weren’t shoehorning a green-dipped Lou Ferrigno into a rambling series of soft, domestically-focused crime dramas, or shoving awkward-looking actors into ill-fitting, spongey costumes for failed pilots and TV movies, small-screen cape adaptations were pretty consistently relegated to the kids’ cartoon slots, however good the latter might have been (*cough*Batman*cough*). It seemed that TV had neither budget nor the ambition to successfully pull off comic books. Only cinema had the chops for that.

But things have changed. Thanks to the likes of HBO and Netflix, TV is now respectable again, more than capable of throwing out serious, glossy, weighty works that can find an audience whatever their tone or subject matter. As Hollywood consistently chases the teen and early-20s wallet, the grown-ups are increasingly staying indoors and binging on more gratifying, long-term entertainment. And as the long-abused comic book, sci-fi, fantasy and horror genres progressively filter into that newly invigorated TV programming, it’s becoming very clear that perhaps our living rooms are where this stuff can find a treatment that really does it justice.

The quality is now – finally – there, but so too, as it always has been, is the structure. Because if we look at comic book storytelling, if we look at what makes it compelling, and compulsive, and allows it the complexity and variety that Marvel is trying to transport over to cinema, what works better for such open-ended, episodic adventure than a format that can drop 10 – 15 episodes at a time?

Matt Murdoch? I know who he is. I know him really well, and that makes everything he does through matter to me a great deal. Thor? Cool guy, I guess. Only met him in passing though. It’d be good to hang out more, but we never seem to get the time.

For more on comics, capes, and all happenings in between, get yourself hold of a copy of the fresh, all-new, and really rather excellent Comic Heroes, on sale October 9, 2015.