With Baldur's Gate 3, Larian might just manage to satisfy fans of Divinity, modern D&D, and Baldur's Gate all at once

Inside Baldur’s Gate 3, Larian’s most ambitious and challenging game to date

Larian doesn't know how to build Baldur's Gate. Not the game, you understand: making a sequel to a beloved RPG famed for its deep characters and sweeping scope is a task the studio is uniquely qualified for. The problem is the titular city – the one that features in Baldur's Gate 3's reveal trailer, as well as BioWare's entry to the genre two decades ago.

"We're experimenting with it," senior producer David Walgrave tells me. "Usually in a Larian game, if we have seven houses, you can enter every house. You can get into the cellar, and there are people living there. They have one or two quests."

"If we apply that philosophy to Baldur's Gate, we're fucked. We're not going to release in the 21st century."

Welcome to Sword Coast

Another developer might simply treat the largest metropolis on the Sword Coast as a movie set, painting doors into the background to provide the illusion of scale. Unfortunately for Walgrave and his team, Larian has trained its players too well for that. "What's really hard for us is to barricade a door," Walgrave says. "OK, you have a barricade, but I have this iron stick that I can use to break it."

The issue tells you three important things about Baldur's Gate 3. First, that it's far from finished. Second, that it's as much a follow-up to Divinity: Original Sin 2 as its '90s namesake. And finally, that it's a game about problem-solving. It's the latter that makes this the boldest adaptation of tabletop Dungeons & Dragons yet.

Larian spent years chasing Wizards of the Coast, and its commitment to the license is evident from the moment of character creation. It's not only the Tolkien-esque dwarves, elves, and halflings that are represented, but the more peculiar corners of the Forgotten Realms too: the yellow-eyed tieflings, snake-nosed githyanki, and subterranean drow. Within these races are sub-races, with knock-on traits. You can rip a background straight from the pages of the tabletop game too, becoming a charlatan, criminal, entertainer, or folk hero. It's the rulebook made interactive.

"If we apply that philosophy to Baldur's Gate, we're fucked. We're not going to release in the 21st century."

David Walgrave, senior producer

Yet these Realms are unmistakably built on the foundations of Divinity's Rivellon. From the moment you crash land on the Sword Coast, about 200 miles to the east of Baldur's Gate in the wreckage of an organic flying ship, you'll recognise the level design. Where each map in Baldur's Gate 2 was a small snapshot of a forest, say, or a bustling market, Larian's approach is to squeeze contrasting environments together in an overstuffed bento box of questing. Think of the way Original Sin 2's Fort Joy wrapped the beach around the ghettos, prisons, cave networks, marshland and underground fighting arenas of a single island. Larian's Forgotten Realms is the RPG equivalent of Lordran, a comparison only made more apposite by a new focus on verticality: more than once, I watched studio founder Swen Vincke stack objects and climb them onto a higher plane, either to access a new area or prepare for ambush.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Combat is immediately identifiable as the turn-based tactics of recent Divinity games – a high-stakes exchange of spells and sword strokes where the winner is determined by shrewd use of status effects and environmental factors like fire and water. It's also bastard hard: Vincke's two party members are quickly killed by a pack of brains on legs in the first battle after the tutorial. "Managing the RNG factor is very important in D&D," he deadpans.

The tabletop game has inspired Larian to introduce a sense of freedom to the way in which you are able to approach fights. A set of action commands allows you to not just move and attack, but to dip an arrow into a burning pool of oil, or push an enemy into it. This is a system for storytellers as well as tacticians.

Embracing change

Frankly, it's easier to see where fifth edition D&D has been wedded to Divinity than, say, Baldur's Gate. Some will be disappointed by the decision to move on from Bioware's real-time-and-pause system, later mimicked in Dragon Age and Pillars of Eternity. The story, meanwhile, concerns an incursion of tentacled mind flayers a century after the events of the earlier games. You can understand why: those adventures and their central prophecy were comfortably wrapped up by the summer of 2001. But what makes this new game Baldur's Gate at all?

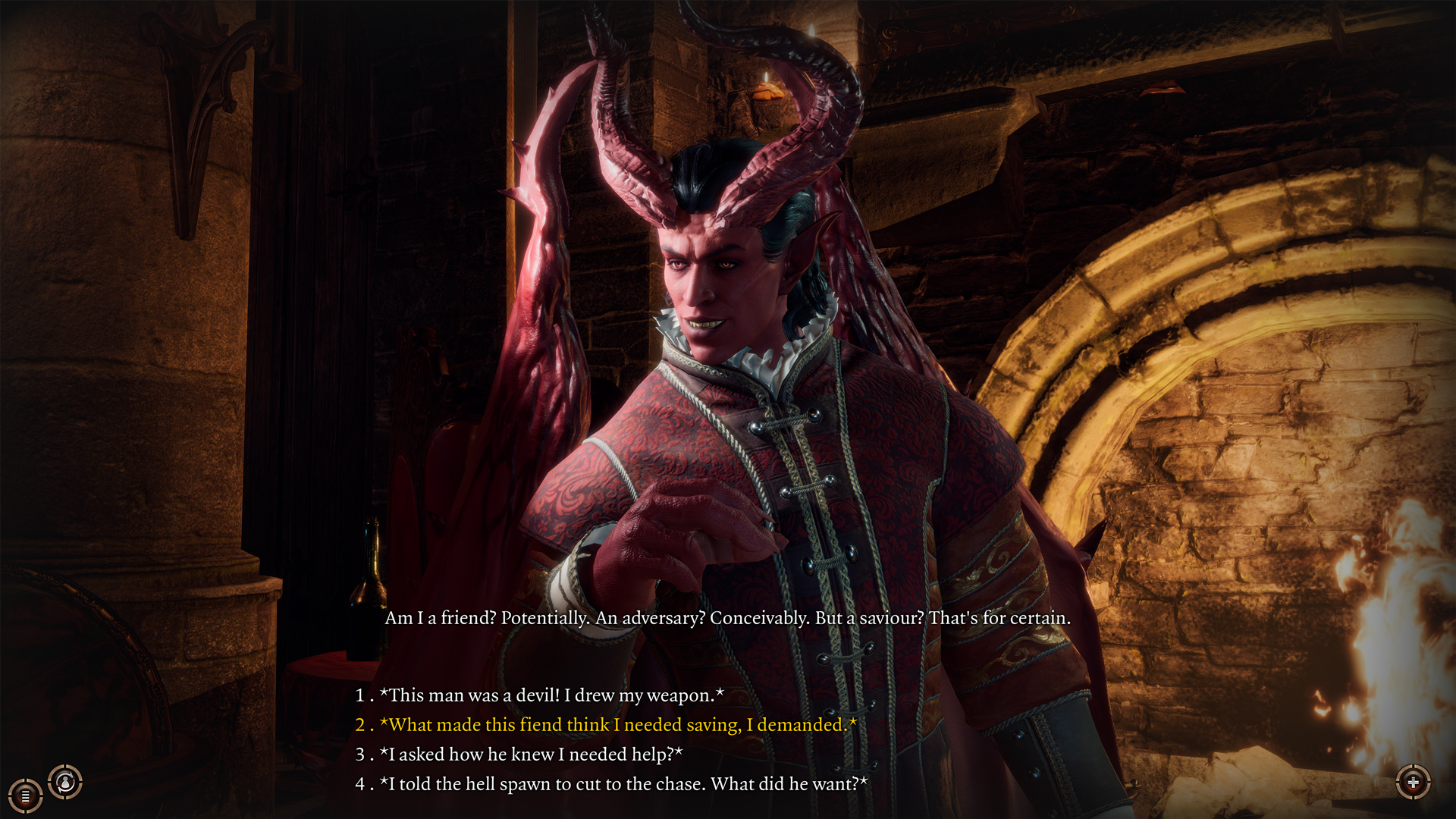

"There are a lot of themes coming back," Walgrave says. "In Baldur's Gate you were a Bhaalspawn, and had this dark partner riding along." This is true: as a child of the god of murder, a latent evil lurked in your blood, and you would ultimately fight or embrace it. In Baldur's Gate 3, that dark partner is a tadpole planted in your brain. It threatens to consume you and your party from the inside, turning you into mind flayers.

The quest to stop that horrific reproduction process forms the backbone of the plot – but the side effects can be handy. Hosts can 'mind meld' with other victims, communicating telepathically and circumventing combat encounters by flexing their new brain muscles. "The problem is that every time I use the tadpole's power, I'm giving into it," Vincke says. "And that's not necessarily a good thing."

"Larian spent years chasing Wizards of the Coast, and its commitment to the license is evident from the moment of character creation"

A slow-burn death sentence which grants terrible power? That's quintessential Baldur's Gate. So, too, is the foreknowledge with which you're encouraged to tackle combat. Back in the '90s, Bioware had a habit of steamrolling your party with a barrage of spells in the opening moments of a battle, leaving you to reload a save and summon all of your cunning to overcome the onslaught. By the third or fourth try, you might have positioned your rogue for a backstab, or commanded your wizard to start their fireball incantation, even before the enemy had finished their opening speech.

Baldur's Gate 3 is much the same. Days into demonstrating familiar sequences to journalists, Vincke takes obvious pleasure in exploiting his experience. In one instance he climbs around the back of a ruin claimed by bandits and shoves a troublesome archer off a ledge, taking the vantage point for himself. In another, the whole room holds its breath as Vincke's hero jumps into the blind spot behind a goblin boss, planting an explosive barrel behind his ankles, then igniting it once battle breaks out. There's real tension, and deep satisfaction, to be derived from this cheesy form of tactical planning – one that'll be well understood by Baldur's Gate veterans.

The challenge ahead

Despite that 100 year time difference, there will be more overt echoes too. Namely, cameos. "We know that we have to," Walgrave says. "People expect it. Even if it is 1492, because we're working with Forgotten Realms, you're still going to meet certain characters that everyone knows from playing the games."

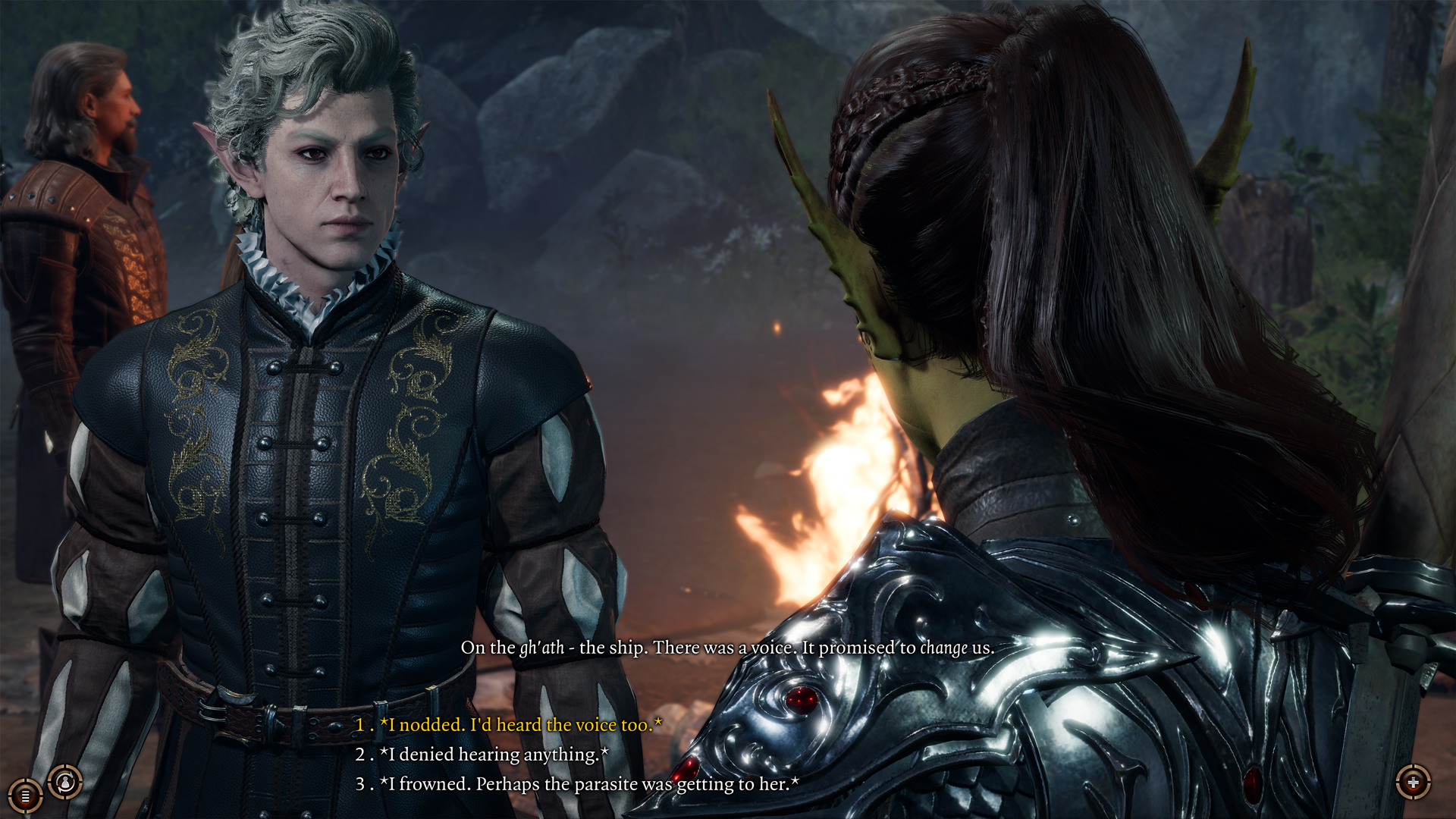

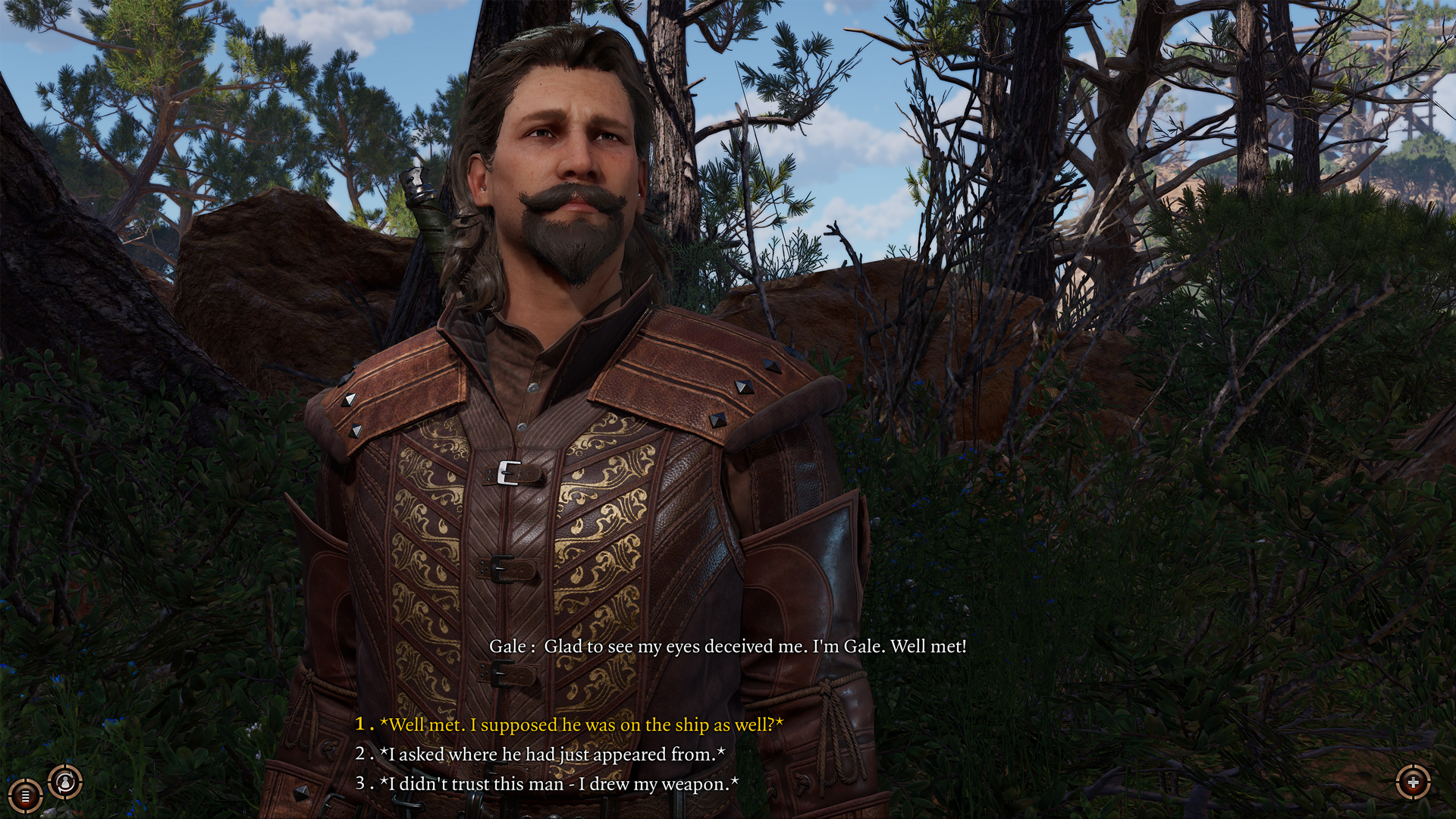

It's likely, though, that you'll soon be attached to new companions rather than thinking of old flames. One is Astarion, a vampire spawn in thrall to a distant master he cannot disobey, who unexpectedly finds himself thrust out into the daylight. Another is Lae'zel, a githyanki, whose people were enslaved by the mind flayers once already. Uncomfortable power dynamics are a favourite theme of Larian's, as are hidden, second identities.

Like those in Original Sin 2, companions are playable as origin characters, giving you a rough sketch with which to roleplay, and their unique quests tie into the main plot. But their personalities are perhaps a tad stronger than those of the Divinity cast. "They're all reacting to each other and your choices a lot more compared to our older games," Walgrave says. "They're very harsh – if it takes you too long to do what they want, they're gonna leave."

That dissatisfaction will be written clearly on their faces, since for the first time since making Original Sin, Larian is zooming right in to capture conversations in the style of Mass Effect or The Witcher. Right now, those visuals leave a lot to be desired – faces twitch and animations reset with disturbing regularity.

Which brings us back to that first lesson: Baldur's Gate 3 isn't finished. It won't even be finished when it first releases, in early access. But Larian doesn't view ambition as optional when it comes to this particular game. "People have certain expectations, and we are probably making choices that not everyone will be happy with," Walgrave says. "But we are aiming for such a high quality game that when they play it, they'll go, 'Yeah, this is Baldur's Gate 3'. We wanted to make sure we deserve the '3'."

Find some modern classics to keep you going while you wait for Baldur's Gate 3 in our list of the best RPG games. And if you want to try the game that started it all, here's how to play D&D online.

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.