How HBO's Barry helped me heal

How do you explain trauma to someone who doesn’t understand? Enter Barry

HBO’s Barry is not the show you think it is. On the surface, it’s about a former marine turned reluctant hitman who wants something more out of life. Underneath, it’s a clever meditation on trauma, the healing process, and finding a purpose for the pain.

As a repeat survivor of assault and someone who suffers from Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and finds comfort in pop culture, I am always looking for myself on screen. I’m always searching for relatable moments that make me feel less alone, for creative (but accurate) depictions of what I live through every single day. This also allows me to better explain the disorder to family and friends who just don’t get it. My mom has never experienced a panic attack, but she understood how I felt when Hank Schrader suffered one in Breaking Bad. I’ve never been able to accurately explain the extreme paranoia caused by PTSD, but I was able to after season one of Better Call Saul and the realistic depiction of Chuck’s psychogenic illness. It’s important. It’s healing. It lets me, and other survivors know, that other people get it. They get us.

Trauma, however, is an entirely different ballgame. It changes the way our brain works and resets our entire personalities, the way we do things, and robs us of ordinary everyday experiences. How do you explain that to someone who doesn’t understand? You can’t – and it’s an impossibly lonely feeling.

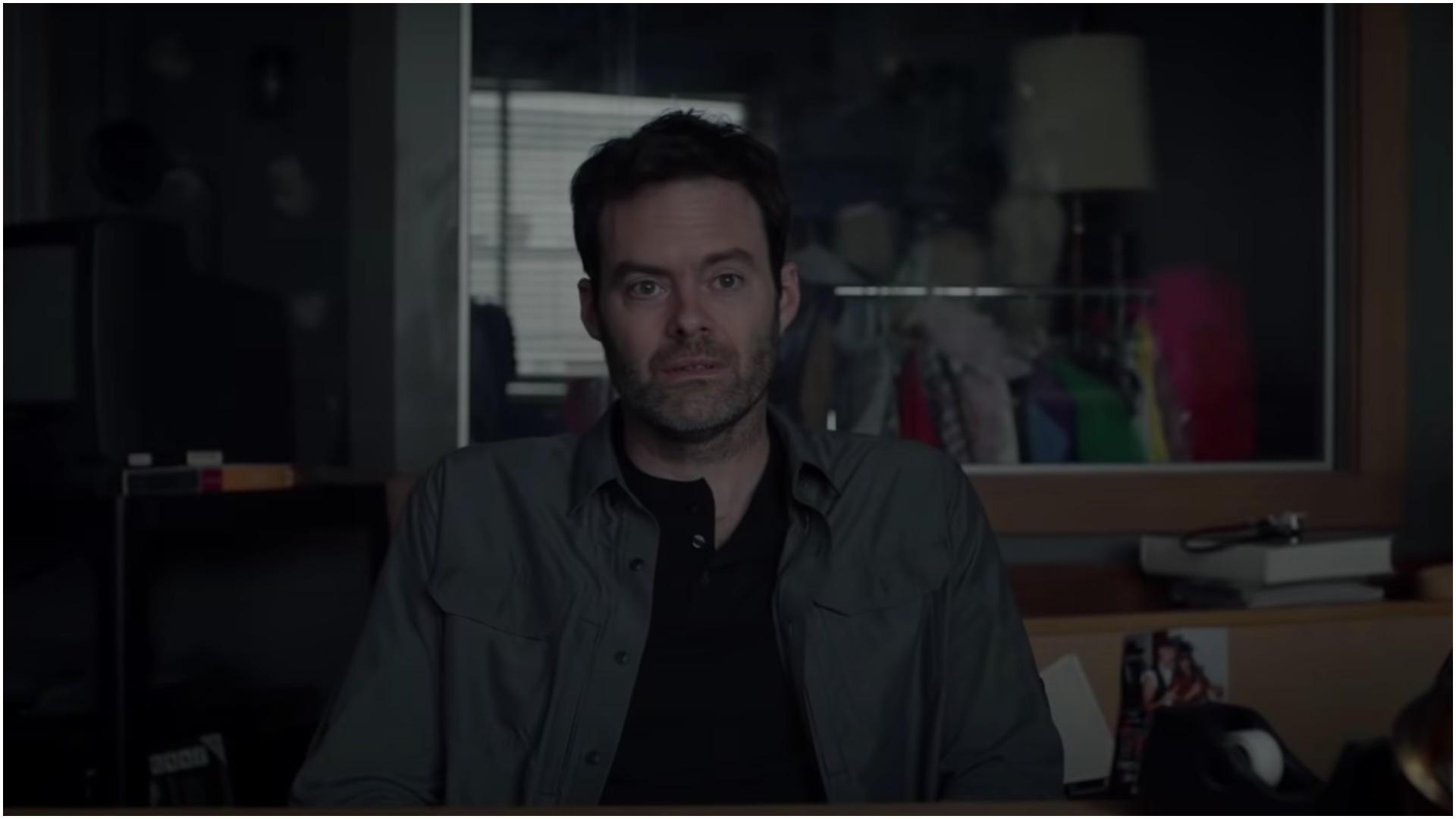

Enter Barry. When we first meet Barry Berkman (Bill Hader), we watch him kill a guy, go home, play video games, and go to sleep as if it were a typical nine-to-five. His next assignment leads him to Los Angeles, where he stumbles upon an acting class full of eager hopefuls with big dreams of making it in the biz. The class is taught by famed acting coach and author Gene Cousineau (Henry Winkler), who believes that a good actor uses raw, unfiltered emotion – often berating his students in order to trigger an honest emotional response.

The longer Barry spends taking the class, the more he finds himself revisiting his darkest moments. His determination to become a better actor is directly intertwined with his desire to become a different person, a better one, and this newfound passion is what ultimately helps him finally begin the (rather difficult and tumultuous) healing process. Though, he’s not the only one. Barry meets Sally Reed (Sarah Goldberg), an aspiring actress with an enormous amount of talent, who immediately becomes his love interest. Sally eventually tells Barry about her abusive marriage, and that drawing on that pain in her work helps her manage it.

The show poses an interesting question, one that no therapist of mine has ever thought to ask: what if there was a purpose for this pain? It throws out the dated trope of ‘trauma makes you stronger’ and asks instead: what if you could take it and turn it into something beautiful?

This is something I had never, ever considered. The poetry I write, which draws heavily from my experiences, has always felt self-indulgent. Have I subconsciously been trying to heal myself this entire time?

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Maybe, but it’s not just the healing and coping methods that make this show important. Barry is brutally honest in its depiction of PTSD, accurately presenting it in a harsh, un-aesthetic light and showing all of the tears, rage blackouts, and broken glass that often come along with it. The show is not subtle in its portrayal, with HBO airing a bumper before certain episodes of season 2 that read: ‘The following program contains Posttraumatic Stress Disorder – and it’s okay.’ I needed to hear that, and I know that so many others needed to hear it, too.

But it’s not okay for Barry. He wants to be anyone, anything else except himself, which is what drew him to acting in the first place. When Barry tells Sally that he can’t play a priest who abused young boys, Sally tells him, ‘You don’t need to know what it’s like, you just need to know what it’s like to hurt someone.’ And this is something he knows well. Barry is wracked with guilt every time he kills someone out of necessity, but it’s drawing on the trauma of these terrible moments that ends up producing his strongest performances as an actor. Hader is devastating in his portrayal, it’s his performance that allows those of us watching at home that feel ashamed or guilty about the ugliness of their trauma to feel a little bit less alone.

It’s the healing process at its most chaotic, its most turbulent: it’s the cycle of finally feeling like you’re getting somewhere, and then falling right back into an old pattern.

This happens to Sally in season 2, which sees the return of her abusive ex-husband Sam. She decides to write and perform a scene based on the night she left him, and pens the ending as one where she stands up to him. But when Sally agrees to sit down with him in person, she’s terrified. Everything becomes muddled and messy for Sally, something that is highlighted by Goldberg’s incredibly strong performance. Recognizing this, Sally decides to work through her trauma by being honest and ends up rewriting the scene to include a direct address to the audience where she refers to the abuse as a cycle she couldn’t break. This story arc effectively tears down the age-old dismissive question: Why didn’t you just leave? It educates the masses, it shows anyone and everyone with that type of ignorant mindset that no, we couldn’t just leave. It’s a cycle. It’s hard. And it’s something that never leaves us.

Barry can’t seem to break the cycle of killing innocent people, ones whose only crime is possessing knowledge that could put him in prison. Each kill brings him closer and closer to the person he was in the Marines – a man who was discharged after killing an innocent civilian in front of their family. Barry shares this story with Gene, and asks, “Do you think I’m a bad person, Mr. Cousineau?” Gene replies with what is perhaps the most important line and best summary of the entire show: “I think you’re terribly human.”

That’s what we are. We trauma survivors, the ones who have acted out in a fit of rage, who say things we can’t take back, or break glass, or hurt others while we’re stuck in survival mode – we’re terribly human.

Barry is a show that isn’t afraid to be terribly human – something that makes it an incredibly important watch. The series uses acting as a clever metaphor for the performative ways in which we display our truths, and offers a way to make sense of our pain, rather than just display it as something hopeless and never-ending. It’s realistic in its portrayal of trauma. It’s allowed me to view my own healing process in a completely different light, one that lets me know it’s okay to be like this. I found myself on screen in both Barry and Sally, and I know other survivors have, too. I feel seen and heard and understood – and I can’t wait to see what else this show has to offer.

For more, check our list of true crime documentaries that put the victims first.

Lauren Milici is a Senior Entertainment Writer for GamesRadar+ currently based in the Midwest. She previously reported on breaking news for The Independent's Indy100 and created TV and film listicles for Ranker. Her work has been published in Fandom, Nerdist, Paste Magazine, Vulture, PopSugar, Fangoria, and more.