Best Shots review - Batman: Year One is more inspirational (and influential) than Frank Miller's Dark Knight Returns

Making the argument for this as Frank Miller's BEST Batman story

Not everyone has written a Batman ur-text, much less two, but Frank Miller ended up doing just that, in consecutive years to boot. Batman: Year One is the alpha to the omega of The Dark Knight Returns. As influential as both have been, a case can be made that the former has had a greater effect on creative teams since because it is a starting point for them to build off of as opposed to the end of Bruce Wayne's crusade.

Written by Frank Miller

Art by David Mazzucchelli and Richmond Lewis

Lettered by Todd Klein

Published by DC

'Rama Rating: 10 out of 10

Looking back at the four issues – released in the wake of Crisis on Infinite Earths and as a response to DC executives looking to revamp the origins of the DC Trinity – almost 35 years after their production can almost make their scale seem quaint. In just shy of 100 pages, Miller, David Mazzucchelli, Richmond Lewis, and Todd Klein craft a narrative where each moment has been carefully chosen and almost all of them have become influential in their own right. That economy of storytelling is the most staggering component of the book.

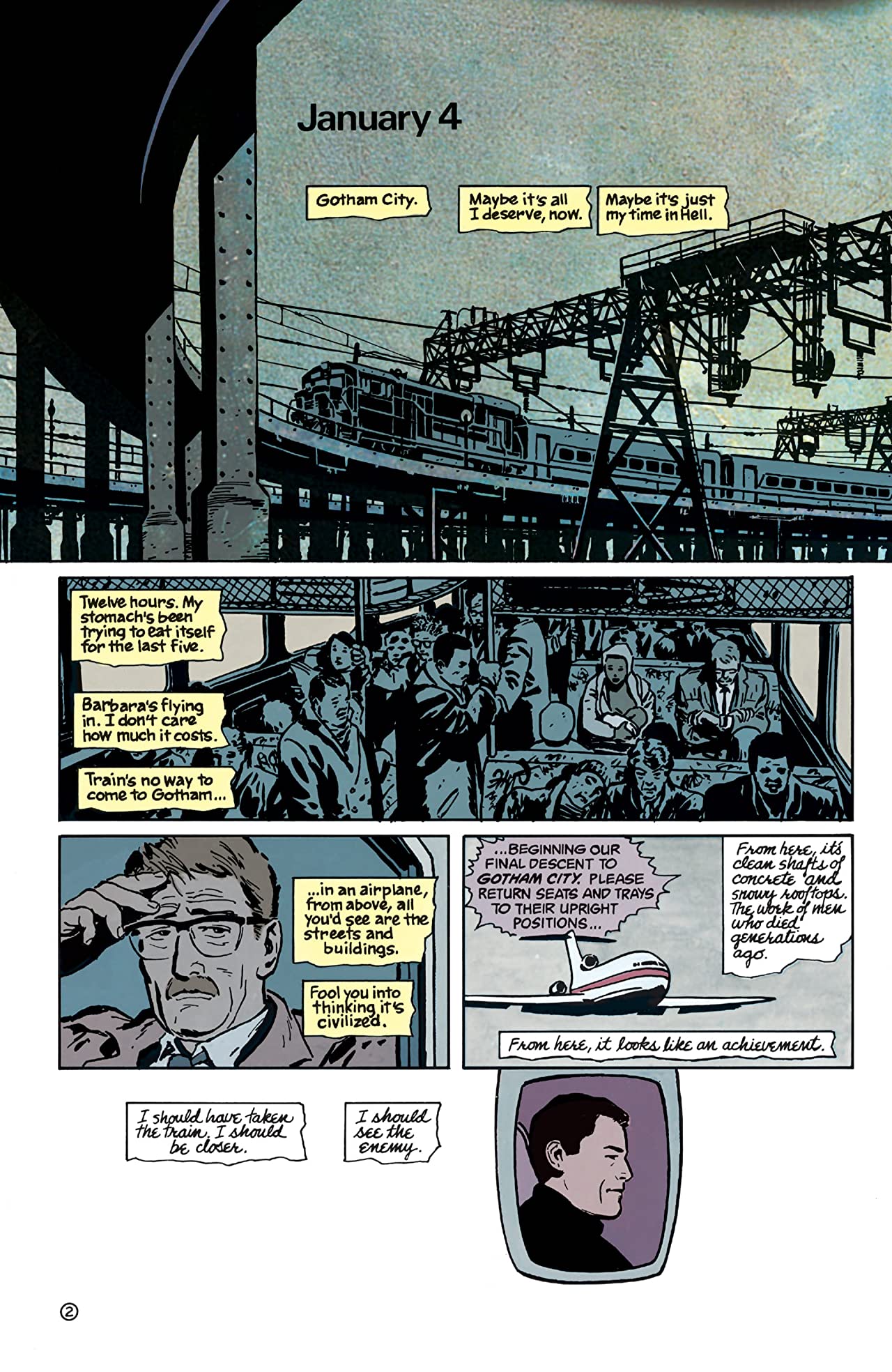

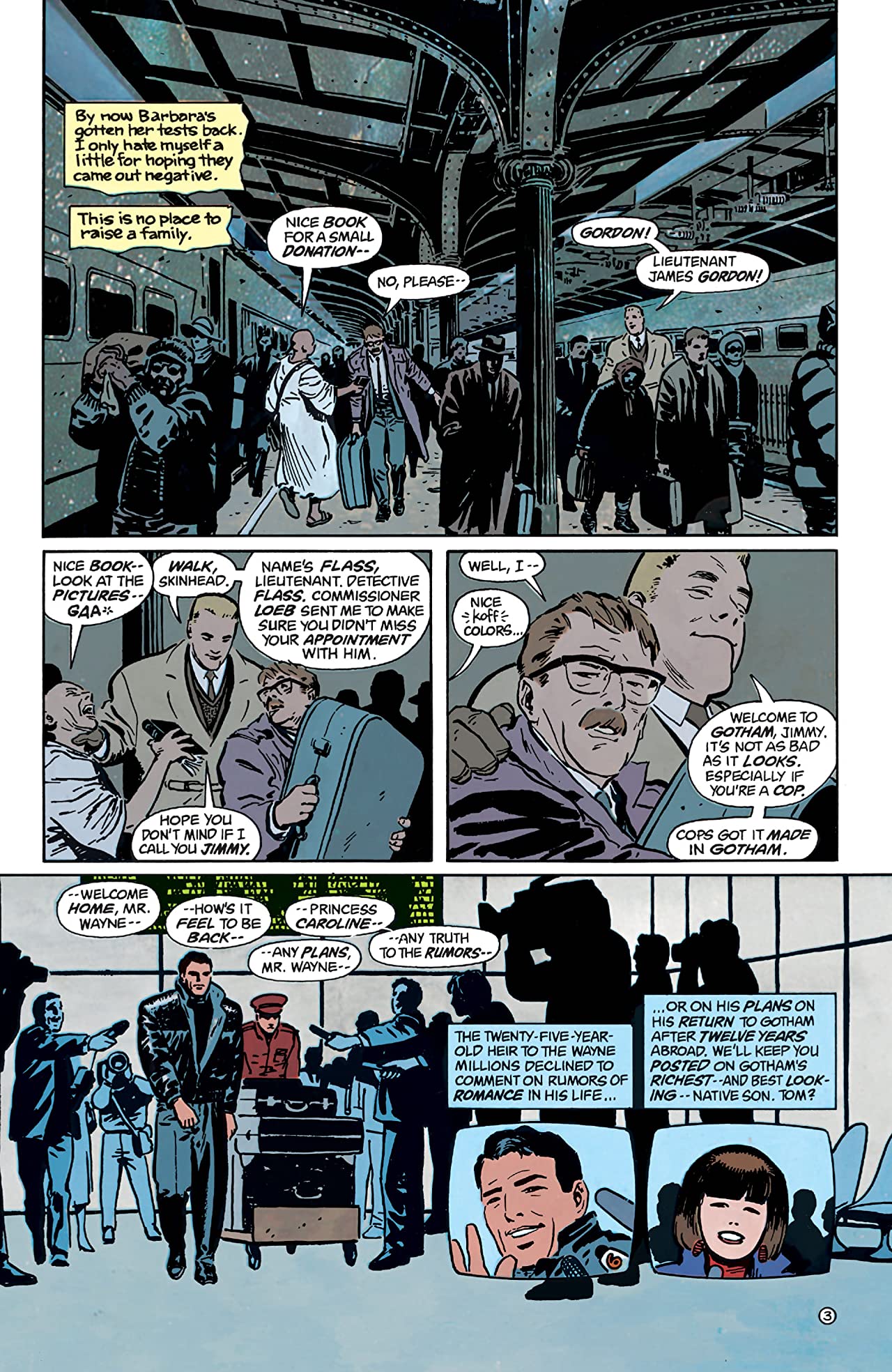

Consider the first two pages. It's January 4 and James Gordon is just arriving in the city, having taken the train. He's not thrilled about it. At the same time, Bruce Wayne returns after years away via plane. Over the course of the year, their experiences become more directly entwined, but the creative team deploys this visual grammar from the outset to connect them in preparation.

Even more fascinating is the choice regarding scale. While en-route to his former home city, Bruce remarks that he should have taken the train, in order to see the enemy. Rather than letting air travel allow a birds-eye view, Mazzucchelli and Lewis play into his viewpoint by depicting his arrival as a much smaller component of the sequence than Gordon's. As such, his three panels across these pages are:

- One which takes up no more than an eighth of the page, depicting the plane; the grey sky providing ample space for Todd Klein's mix of a pilot's instructions and legible cursive writing of his protagonist's thinking.

- Bruce, in profile, through one of the plane's windows. The sleek, white paint job of the aircraft functioning as negative space so further thoughts can trail behind as it runs along the bottom of the page. The emphasis on the character also shows just how precise Mazzucchelli's linework can be in its simplicity.

- Bruce walking through the airport, ignoring questions from the press. The panel takes up even more real estate on the page than the previous two combined, and yet even with two overlaid panels and two accompanying captions, the space feels much less cramped than Gordon's traversal of the train platform as commuters pass through the space.

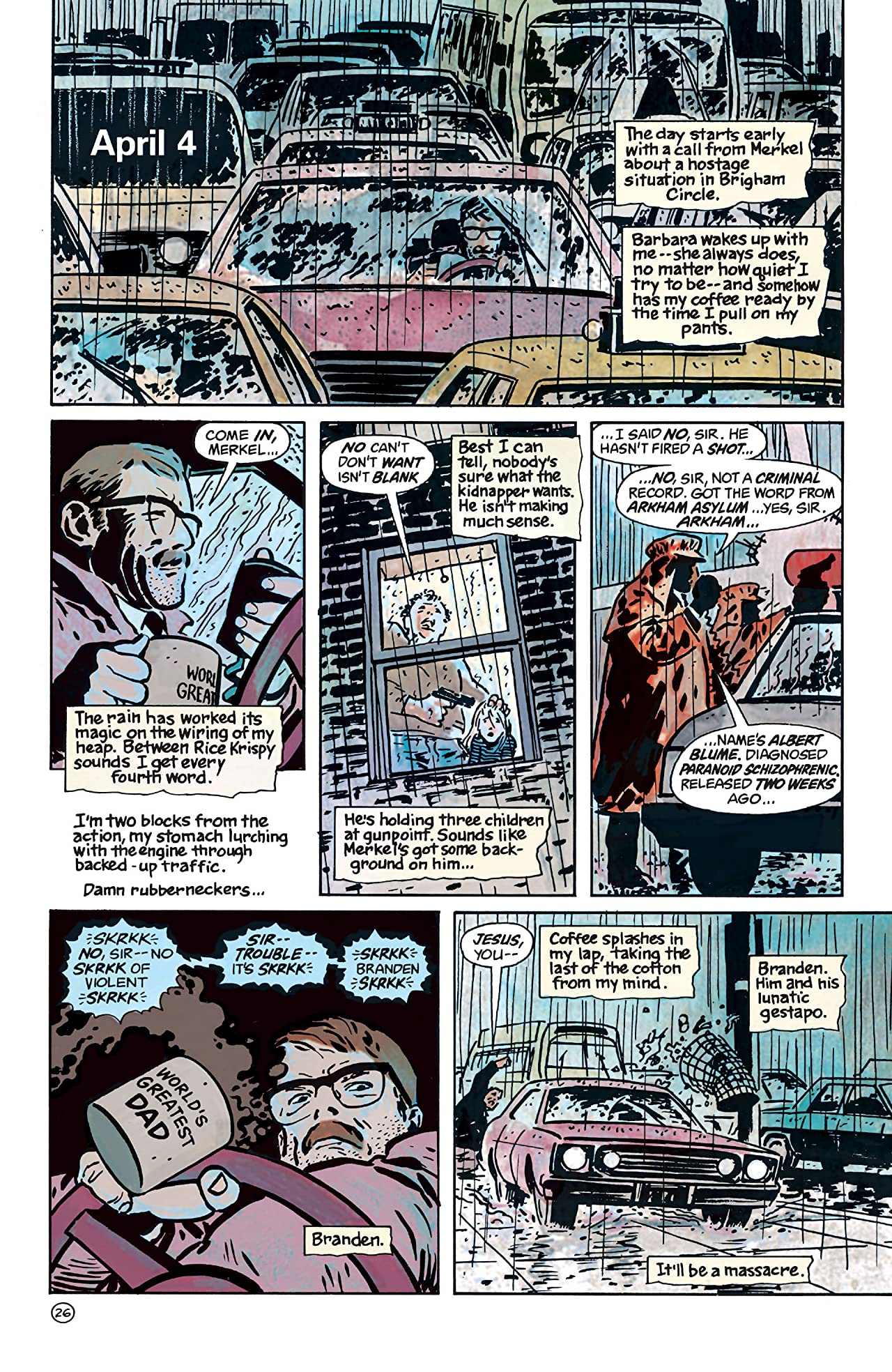

Bigger moments than this follow. The first issue alone contains a car chase, Bruce's training regime at Wayne Manor against the tree, Gordon's beating at the hands of the corrupt Lieutenant Flass and his men, Bruce's scoping out of the East End and subsequent fight with a street pimp (an event which also involves Selina Kyle), Gordon's revenge, Bruce's escape from police custody, his wounding and a flashback to the death of his parents. All of which coalesces in his decision to become a bat.

Yet the book never feels as if the creative team is straining to cram these in. Each moment still has its time to breathe, even when they take up a similar amount of space as Bruce's return. In essence, the pacing is akin to a novel made up of just the verbs, but this streamlined narrative direction is conveyed with an undeniable noir-influenced texture via the craft. Light and shadow are fighting it out just as much as the wider ideas of good intentions and evil machinations.

In counterbalancing this emphasis on moments, Year One is also a book structured around the deliberate use of ellipsis. Days, weeks, and sometimes months are skipped past in the transition from one panel to the next. The effect this accomplishes is something that I would argue many usually skip over when discussing the issues. As much as this book sees Miller and his collaborators dive into the nitty-gritty of a street-level story, these time jumps are what allow them to still contain a mythic quality to proceedings.

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

Think of the sequence where Gordon goes to visit Harvey Dent as part of his inquiries. He talks about Batman knowing when and when they set their traps with some sense of amazement in his voice and just as soon as he's gone, the creative team pull back from the close-ups to a reverse shot of the room, revealing Batman behind the desk. These six – just six! -- panels have an entirely human factor of Bruce hiding just out of view while still building up the figure of the superhero, not to mention suggesting a narrative thread in Bruce and Harvey teaming up.

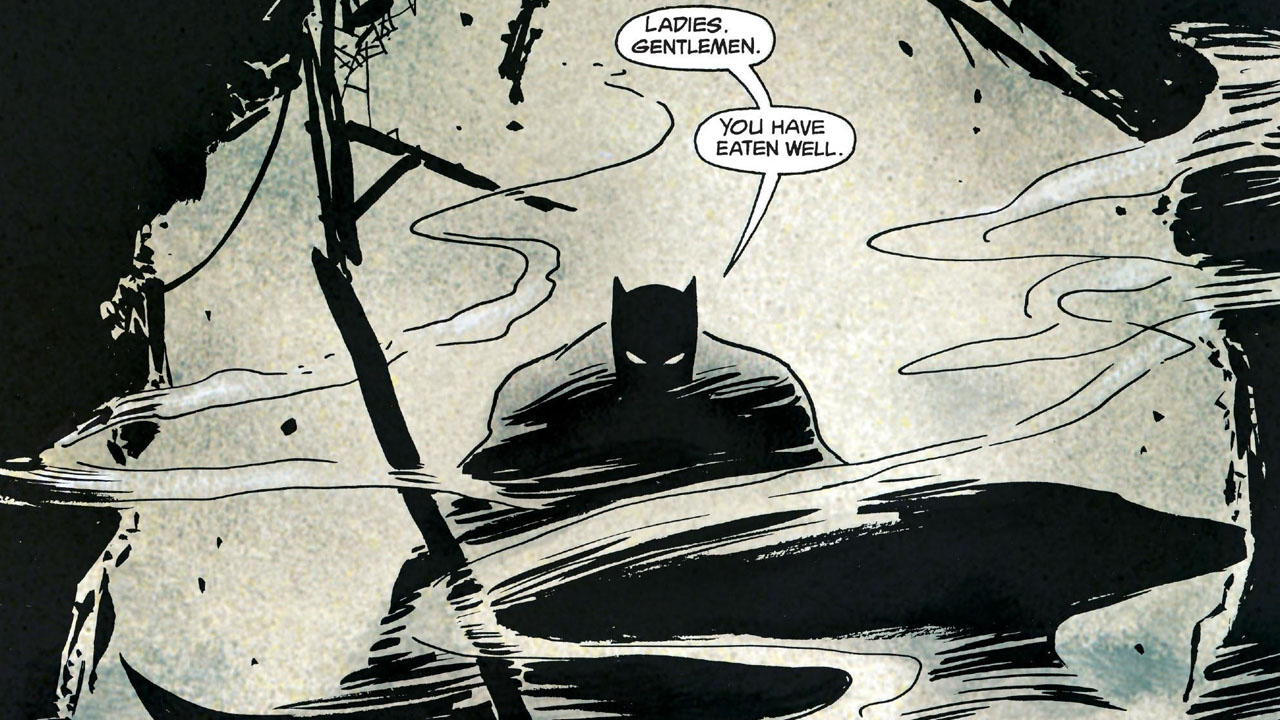

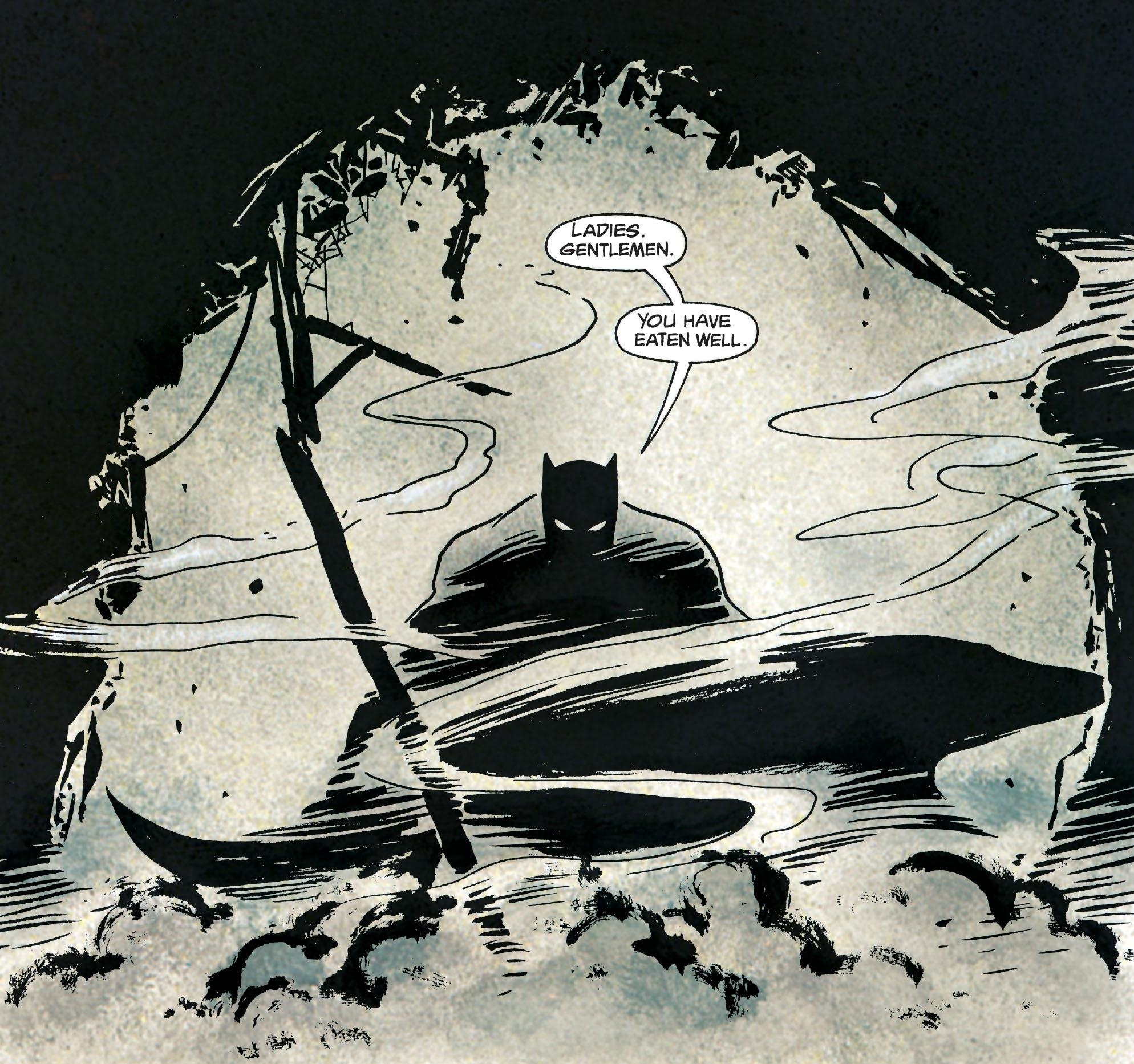

Or consider the sequence that takes place at the Mayor's mansion on the night of May 19. The team cut between the interior of the location where the Gotham elite (and corrupt) dine and the exterior where Bruce methodically works his way into position: subduing staff, preparing lights, and pulling the pins on smoke grenades. It all builds to the two-thirds-high – the biggest panel as of now – visage of Batman through the broken wall and billowing smoke as he claims "Ladies. Gentlemen. You have eaten well."

A mythic image as much as it is a nightmare, but not one that exists in isolation. Its power comes from the sequence's build-up. The cross-cutting between spaces. The contrast between the high-intensity light inside that makes these figures of power look even more gaunt and the depth that Lewis paints in the establishing shot with his uses of blue, green, and yellow. It is a sequence built around suspense rather than surprise, punctured by the breaking of the glass as the smoke grenade crosses the spatial boundary and the subsequent explosion connects them. Bruce concludes by saying "From this moment on, none of you are safe." And how could they be? The divide has been broken down.

The palpable sense of terror struck up in this moment is perhaps why reading Batman: Year One is the only time that Bruce's crusade has seemed plausible as something that can be accomplished, rather than something that will never cease. And in order to achieve this, the book does admittedly partake in some thematic angles that grow further outdated the further away from that moment we get.

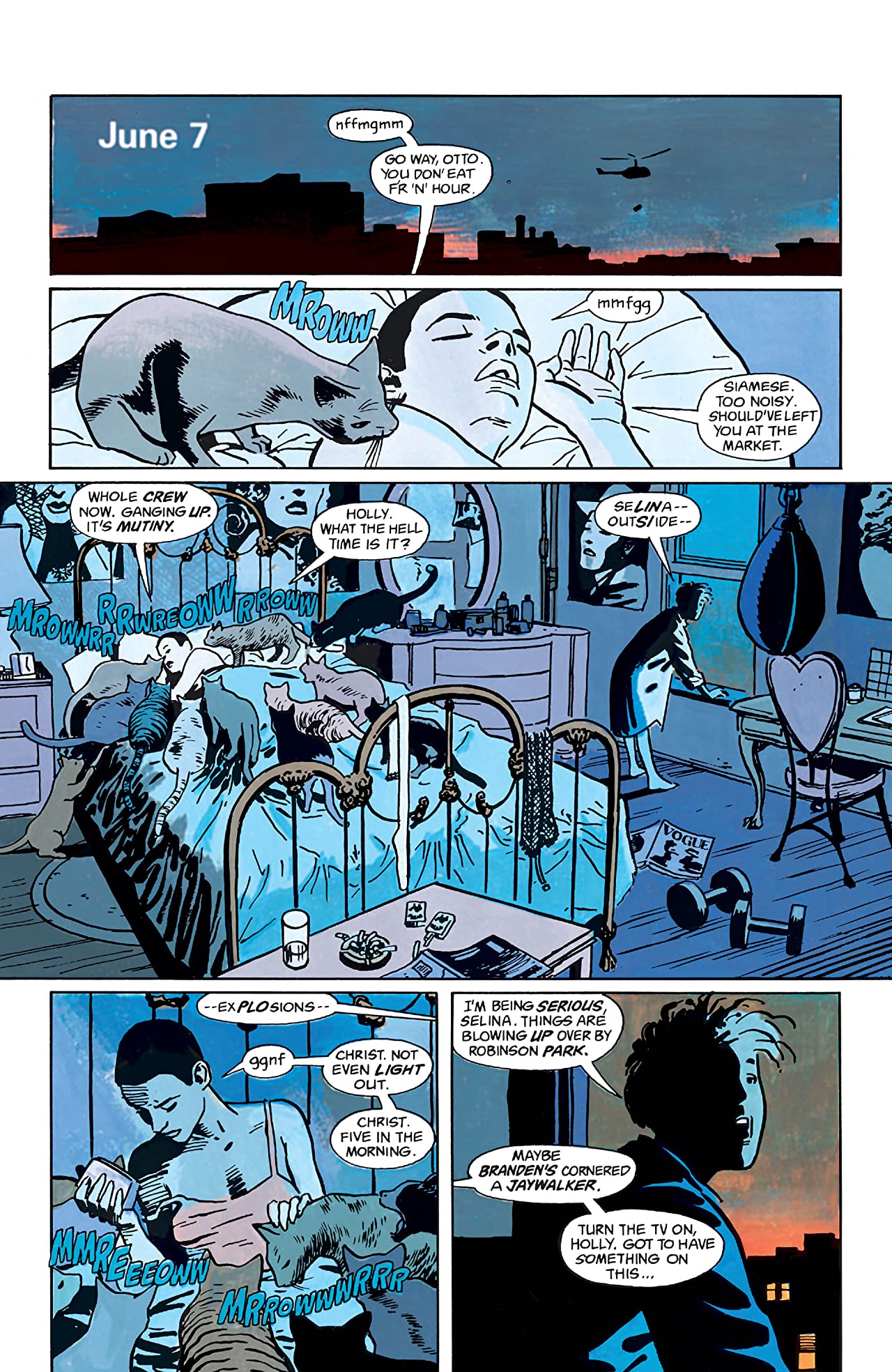

One of these concerns the role of women. Like Selina who exists primarily as a sex worker within the chosen milieu. Her own origin story is elided in the time skips and as such, her brief appearances over the course of the narrative don't allow her to be further defined, even when the team shows elsewhere how much they can do with so little. Though this is admittedly balanced out in this critic's eyes due to how the team treat Detective Essen, her personal and professional plotlines never make her the bad guy and that as much as Barbara Gordon exists on the periphery of everything going on, Mazzuchelli's minimalist detailing of her expression when she does exist in the foreground of a panel (set on October 5) manages to say so much about her emotional state.

Another of these concerns Gordon and thus has a more overbearing effect on the book. This is that he is treated as one of the good ones within the police force. He might not be alone, Essen is on his side, but they do find themselves seemingly outnumbered by others like Flass and Loeb who perpetuate the corruption in order to further benefit from the broken system.

While Bruce's crusade comes attached to a degree of pulp and mythic depiction of a larger-than-life hero, Gordon is the perspective within the narrative most aligned with the street-level view. By now – and something that should've been evident even at the time of publication considering the public awareness of those like Frank Serpico – the idea of a good, well-intentioned person becoming a cop with the belief they can reform an institution built upon decades of systemic abuse seems foolhardy. (It's why one of Steve McQueen's 2020 works - Red, White, and Blue - cuts off abruptly at what would usually be the break between acts two and three – the point is obvious, and eliding it makes it all the more apparent than choosing to narrativize it).

Yet, at the same time, when the time comes for the book to conclude, the team does so with Gordon. As he reflects on the past year, he notes that someone worse is on the way in two regards. One of these is a coy reference to the Joker – a choice that has now been further immortalized by the ending of Batman Begins – the other is a member of the force primed to take power and is allegedly worse than Loeb.

If this is a book constructed around moments, and this critique is couched in the belief in the weight that even the most minor of those hold, it would be negligent to not acknowledge the importance of the decision to leave off on these thoughts over a purely triumphant image of Batman saving the day. Aspects like this create a sense of Gotham existing beyond the front and back covers; before Bruce and Gordon's concurrent arrivals and after their blossoming partnership begins. There is also a sense of Gotham existing beyond what Mazzuchelli and Lewis depict within their panels, though the implications of such suggest that the parts not explored within the book fare any better.

Batman Year One has a streamlined quality to it that can make it seem small in scale – especially when compared to the prestige-length format of The Dark Knight Returns – despite the extent of the crusade. The work that Miller, Mazzuchelli, Lewis, and Klein put into building Batman up into something so big is that much greater seeming because they're looking up at it from the street-level. In doing so, they also establish a city rife with corruption, crime, and depravity, even before any of the rogues' gallery show up.

The book has had an undoubted and wide-reaching influence on creators since, that much can be seen in how this is the benchmark that many subsequent depictions of Batman and Gotham have attempted to emulate. Perhaps it can't be changed, and perhaps that's because Bruce's crusade doesn't end in any other way than that which Miller designed with The Dark Knight Rises – creative a recursive and ultimately doomed cycle. But perhaps Batman: Year One's foremost influence is the knowledge that the book is the work of masters of the form, at the height of their powers, delivering their particular vision. Its inspiration should be to encourage creators to pursue their own particular visions most of all, because perhaps one of those could end up being just as influential.

Spoilers, but Batman: Year One is on the top of our list of the best Batman stories of all time.

Matt Sibley is a comics critic with Best Shots at Newsarama, who has contributed to the site for many years. Since 2016 in fact.