Blood, death, and robots: Breaking down the key ingredients of the cyberpunk genre ahead of 2077

Here's what makes a game like Cyberpunk... well, cyberpunk

As Cyberpunk 2077 approaches release, perhaps even for real this time, it holds the promise of a complete cyberpunk experience. CD Projekt Red's RPG certainly looks the part, promising tales of shady corporations, violent street gangs, and extreme body modifications that seem set to explore many of the sci-fi genre’s classic fantasies.

But cyberpunk is all of these things and so much more. Across films, books and games, the genre has always been a tangled mixture of concepts, aesthetics, and themes. It’s about the style, the grit, and the danger. It’s about technology, from flying cars to androids, cyborg augmentations and biological implants. And it’s also about questioning who we are as people, and what we become when faced with identity-altering gadgets, hyper-commodification, and oppressive power.

With all these different elements, what would it really take to make the ultimate cyberpunk game. Ahead of 2077, we've looked back through cyberpunk’s history to create the ideal combination. Below are 11 essential ingredients for the ultimate cyberpunk experience, with a respective game for each to illustrate how they might best work. These are all original cyberpunk games, rather than licenses. Some are old, some new, some well-known and some much less so.

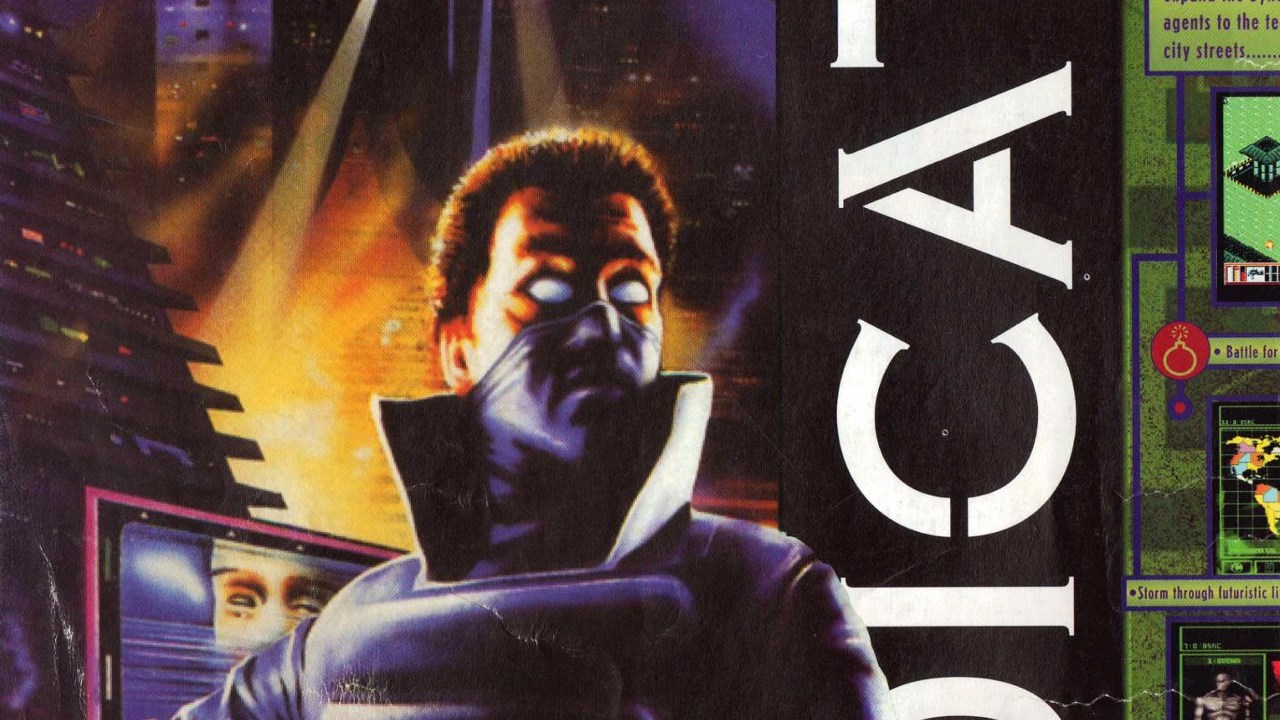

Corporate control – Syndicate (1993)

Cyberpunk defined itself in the 1980s, an age of rampant privatisation and commodification, heavily influencing one of its recurrent fears: a world controlled by mega-corporations. From Blade Runner to Snow Crash, goliath companies control the crucial technologies in cyberpunk worlds, if not every aspect of public life.

Gaming’s most iconic corporate dystopia is still Bullfrog’s Syndicate (not to be confused with the 2012 remake), which put players in charge of a criminal conglomerate, tasked with global domination. What’s chilling about Syndicate is how it simulates the cold distance of inhumane management decisions.

At the click of a button you drain more taxes from your subjects or develop deadly new tech, and can even remotely control agents to kidnap useful individuals or assassinate opponents. Its murder and extortion from the comfort of an executive office.

Social division – Final Fantasy 7 (1997)

Hands-on with Cyberpunk 2077: Freedom, master world-building, and customisable genitalia

Cyberpunk is about contrasts, as corporate and celebrity luxury co-exists with the deprivation of life across society's lower classes. In post-apocalyptic visions such as Judge Dredd or Battle Angel Alita, populations are crammed into huge apartment blocks or forced to scrape by in wastelands, Final Fantasy 7’s city of Midgar is similarly iconic.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Like Alita, it physically divides society with a vertical structure – an industrialised hub mounted on a giant raised plate steadily drains the planet’s Mako energy, while looming over scrap metal shanty towns built below. Final Fantasy VII follows a more activist strand of cyberpunk, however, where it’s still possible to reclaim the world from oppressive powers.

Sentient A.I. – System Shock (1994)

If you spot a self-aware computer in cyberpunk, there's a decent chance it'll start taking matters into its own hands, often with deadly results. From William Gibson’s genre-defining novel Neuromancer, to films such as Tron and The Matrix, we’re terrified the machines will get too big for their boots.

The perfect example of coding gone awry in games is SHODAN, the space station AI from action-RPG System Shock (and its sequel). Everything’s working fine until the game’s protagonist fiddles with the system’s ethical directives, at which point SHODAN decides she’s a god, and either kills the crew or transforms them into mutants and cyborgs.

From there it’s a battle of wits as you attempt to regain control, and she becomes more devious and unhinged trying to stop you. And as with any good cyberpunk computer faceoff, the final SHODAN showdown takes place in cyberspace itself.

Androids – Binary Domain (2012)

Artificial intelligence housed in humanoid robots can also be dangerous, but equally tends to throw up ethical conundrums about the nature of simulated life. Many philosophical questions surrounding robots were posed by pre-cyberpunk writers such as Isaac Asimov and Philip K. Dick, whose work inspired the definitive cyberpunk android movie, Blade Runner.

One game that delves into robo-rights is Binary Domain, from Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio of Yakuza fame. This all-action third-person shooter leaves room among the wisecracks to contemplate some deeper ideas, as you hunt down the creator of outlawed robots that look like people and don’t know they aren’t. There’s also the presence of suave French robot Cain in your squad, which forces you to re-evaluate your trust issues with synthetics, although not before you’ve gunned down hordes of less personable droids.

Hackers – Invisible Inc. (2015)

There’s nothing more central to cyberpunk than cyber-punks themselves. Like Neuromancer’s ‘console cowboy’ Case, these individuals rebel against corporate network control by tapping into their talents for cybercrime, hacking the technology and turning it against itself.

Many games feature hacking mini-games or side missions, but few manage to make digital sabotage as tensely strategic as Invisible Inc. Klei Entertainment’s turn-based roguelike is about corporate espionage, both physical and virtual. To help steal what you need you can remotely hack anything you can see, but it takes time, and security levels rise with every turn. As you wait for your programmes to break down firewalls on company vaults, guards close in your position, and it’s a question of whether you can hold your nerve.

Street gangs – Huntdown (2020)

With lawlessness and desperation come gangs. From the warring motorcycle tribes of Neo-Tokyo in Akira to the psychotic groupings of Night City in the Cyberpunk RPG series, street gangs embody the nihilistic depravity that spreads through so many cyberpunk worlds.

For a properly unpleasant example in gaming, we need go no further back than this year’s Huntdown, an unashamed homage to ‘80s arcade shooters and action films. Under contract by (what else?) a shady corporation, your cyborg mercenary aims to clear the streets of four organisations, from the ice-hockey uniformed Misconducts to the Heatseekers with their penchant for hot rod racing and rock ‘n’ roll culture. Each is controlled by a hierarchy of extra-mean lieutenants who offer up some uniquely satisfying boss encounters.

Cyborgs – Deus Ex (2000)

Cybernetic modification is always a ripe subject for cyberpunk, as mechanical and computerised enhancements create a fascinating dichotomy between the superhuman abilities they bestow and the sacrifices to identity that follow.

Deus Ex is one of gaming’s big cyberpunk classics for many reasons, but its use of augmentations is a core feature that melds with the story’s concepts of choice and consequence. Protagonist Denton can enhance or replace various limbs and internal organs for extra speed and strength, resistances or boosted vision. Choosing which implants to prioritise is perfect RPG fodder, but in a game about multi-path progress and decisions that alter the world around you, it’s equally important to consider what these changes turn you into; man, or machine?

Altered consciousness – Remember Me (2013)

Another means of transcending normal human limits is to manipulate consciousness like computer data, changing lived experiences or uploading personalities to new locations. The ramifications are often explored in cyberpunk via books such as Mindplayers and Altered Carbon, or even manga, most notably in Masamune Shirow's Ghost in the Shell.

An interesting example in games is Dontnod’s Remember Me, which plays with the idea of manipulating memories along with contemporary issues relating to social media and corporate data ownership. The game revolves around a technology that allows people to upload, share and delete memories, while protagonist Nilin is also able to remix other people’s memories to manipulate their behaviour. It’s a premise that leads to various questions about how power controls our thought processes, or the importance of retaining a coherent identity and facing up to reality.

Hi-tech weapons – Perfect Dark (2000)

Not all flashy cyberpunk gadgets have to be out of the realms of reality, and with all the crime around, there’s often a need for more conventional weapons. That might mean beefed up versions of real-life guns, like OCP’s creations in Robocop, or flights of fantasy like Judge Dredd’s multi-purpose Lawgiver handgun.

These two approaches to cyberpunk weapons merge together in one of gaming’s finest purveyors of flashy futuristic firearms, Perfect Dark. Rival corporations dataDyne and the Carrington Institute offer a range of feisty pistols, shotguns, and rifles, all with USPs in their secondary functions. Favourites include the RC-P120 with its cloaking device, the Dragon, which becomes a proximity mine when discarded, and the infamous laptop gun, which folds neatly to resemble a portable computer and can be deployed as a remote sentry gun.

Everyday life – VA-11 Hall-A (2016)

Not everyone can change the world. Cyberpunk is as much about the texture of everyday life as earth shattering events. The minor characters we meet, especially in short story collections, such as Burning Chrome, the Mirrorshades anthology, or Futureland, make these neo-dystopias feel alive.

This more down-to-earth aspect of cyberpunk is the focus of indie visual novel VA-11 Hall-A. It’s a game about running a bar within a surveillance state, learning about your intriguing customers as you fulfil their drinks orders. It goes where many cyberpunk games don’t, drilling down into the trials of life among the demands and potentials in a cyberpunk world. Here, issues of celebrity, sex work, prejudice, and more aren’t just background flavour, they’re central to the human (and animal/android) stories you discover.

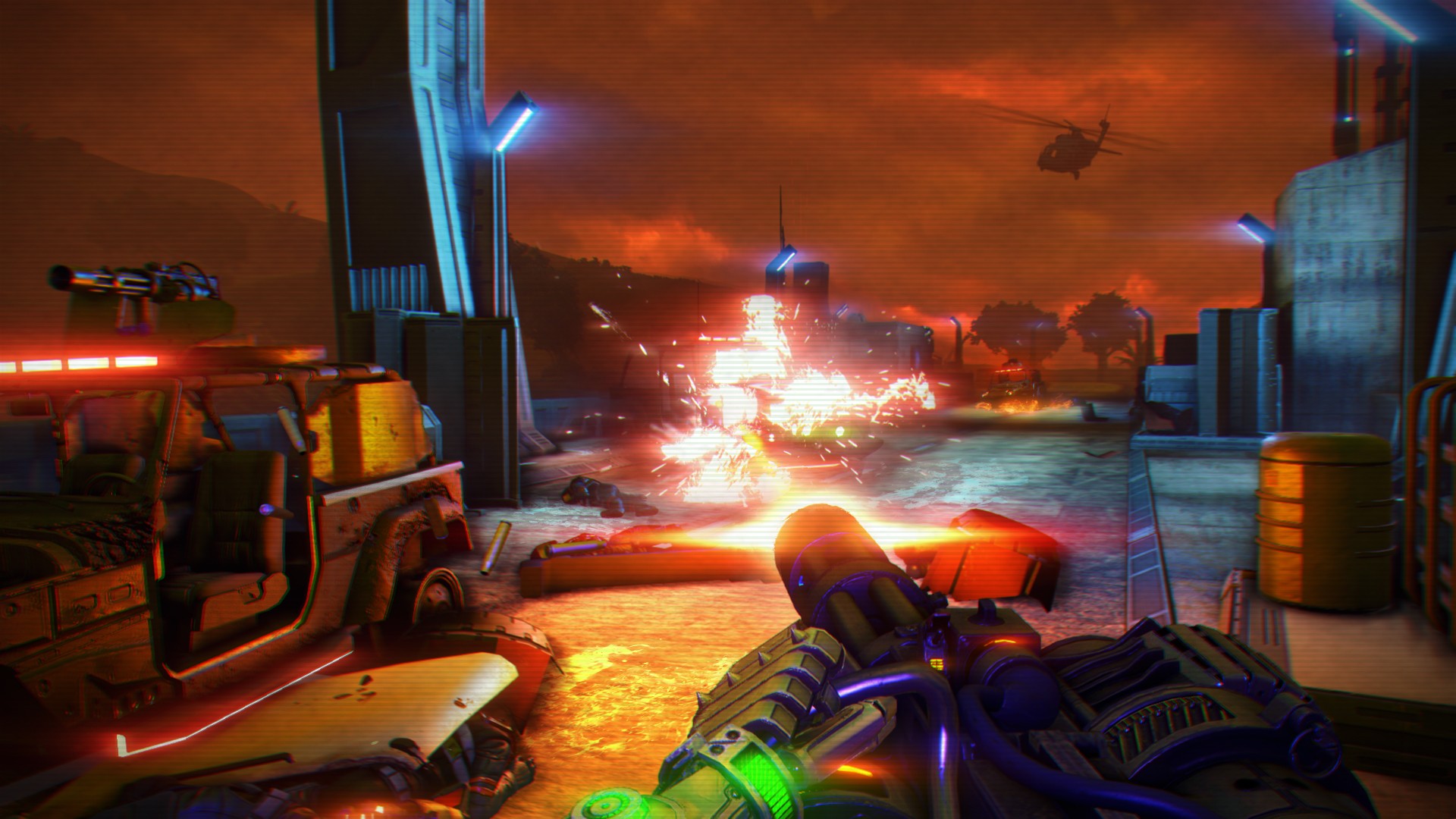

‘80s style (Far Cry 3: Blood Dragon)

Cyberpunk doesn’t have to look a specific way, but it retains a deep connection to the 1980s. In some cases, not least in games, today’s cyberpunk acolytes still primarily focus on that aesthetic, lovingly recreating rain-soaked neon-lit city streets and haunting synth soundtracks.

We’ve already mentioned Huntdown as an ‘80s homage, but for pure neon vibrancy there’s nothing quite so on brand as Far Cry 3's Blood Dragon DLC, which dives headfirst into its glorified sendup of retro-futurism. Littered with lurid purple lasers and shiny metallic buildings, it’s geared towards nostalgia for VHS sci-fi action films. The lead voiceover by ‘80s sci-fi stalwart Michael Biehn, of Terminator and Aliens fame, is mere icing on the cake.

Excited for the game and want to reserve a copy? Then be sure to take a look at our guide on all the best Cyberpunk 2077 pre-order prices.

Jon Bailes is a freelance games critic, author and social theorist. After completing a PhD in European Studies, he first wrote about games in his book Ideology and the Virtual City, and has since gone on to write features, reviews, and analysis for Edge, Washington Post, Wired, The Guardian, and many other publications. His gaming tastes were forged by old arcade games such as R-Type and classic JRPGs like Phantasy Star. These days he’s especially interested in games that tell stories in interesting ways, from Dark Souls to Celeste, or anything that offers something a little different.