How a Final Fantasy box-office bomb led to the strangely charming Blue Dragon

The recent release of Final Fantasy XV offers up a powerful reminder of the strength of the Japanese RPG. FF’s star might not be as high as it was in the late ‘90s, but the series is still an absolute powerhouse in terms of sales and brand recognition. At one point, it was considered a must-have for a console to have a Japanese RPG of its very own even in the West, and with Final Fantasy closely tied to its rival, Xbox had to look elsewhere. Enter Blue Dragon: an all-original game with an incredible pedigree.

How Blue Dragon came to be is arguably just as interesting as the game itself. Don’t get me wrong: the newly backwards compatible RPG is a cult Xbox 360 classic for good reason and is well worth a play even today, but the game also represents a fascinating period in Xbox history: the battle for the Xbox 360 to conquer Japan.

This tale really begins in the summer of 2001 – months before the original Xbox console would release. Riding high on the success of Final Fantasy VII, famed Japanese publisher Square was trying to reach another blockbuster moment – this time in the cinema. The result was the disastrous Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within.

Debates about quality aside, the movie failed to find an audience. It became one of the biggest box-office bombs of all time. The movie’s failure was the catalyst that would lead Final Fantasy creator and movie director, Hironobu Sakaguchi, to eventually leave Square, which would later merge with Enix to become today’s version of the company that’s as well known for Tomb Raider as it is Final Fantasy.

Come 2004, Xbox had been out in Japan for two years and one thing was clear: it wasn’t working. The huge ‘duke’ controller and oversized box certainly didn’t help, but most damning for the console was that it didn’t have any Japanese games. Microsoft had partnered with Sega on the likes of Jet Set Radio and Shenmue but these weren’t enough. In search of a fix, Microsoft turned to the master. Fresh from licking his Hollywood wounds, Sakaguchi was ready to set up a new company. With Microsoft’s financial aid, Mistwalker was born.

After what then Xbox boss Peter Moore later described as ten months of meetings, Moore and Sakaguchi sealed their deal over “a very expensive bottle of sake”. The agreement: Sakaguchi’s new studio would produce two RPGs for Microsoft’s as-yet unannounced second Xbox machine. These were mentioned briefly at an event in February 2005, while the name Blue Dragon would first be uttered in Japanese magazines a few months later.

One advantage of recruiting Sakaguchi was that his name held incredible power even in light of his cinematic misstep. Gamers in Japan and abroad recognised his vision and developers respected him. In this regard the Mistwalker investment was something of a coup for Xbox. In 1995 Sakaguchi put together what he termed a ‘dream team’ of Japan’s five most prolific RPG developers to create the incredible Chrono Trigger. In 2004 he reunited three members of that team – himself, musician Nobuo Uematsu and artist Akira Toriyama – for Mistwalker’s first project.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

While Mistwalker would oversee the project, heavy lifting on development was provided by a rare Japanese studio with Xbox history: Artoon, the creator of two games which featured maligned Xbox mascot, Blinx the cat. With music from legendary FF maestro Uematsu and art from Toriyama, who had previously worked on Dragon Ball and Dragon Quest, the game was already stacking up an impressive case for the Xbox 360 to carve out a stronger audience in Japan.

When it launched in the country in 2006, Blue Dragon did the seemingly impossible: it made Xbox 360 consoles sell. Pre-orders of an Xbox 360 Core and Blue Dragon bundle sold out and stores shifted 80,000 copies in the first week. In 2007 it went on to have modest success in the West as well, receiving fairly decent reviews. In this part of its mission, Blue Dragon was at least partially successful, and with good reason. It’s a decent game.

At the core of Blue Dragon sits smartly designed gameplay built from the most enduring of traditional RPG tropes. Blue Dragon’s lineage traces back more into Dragon Quest than Final Fantasy, and it’s from that relation it gets its Toriyama art and its more traditionally skewed vision of turn-based combat. The result is more methodically paced battles. While many others pushed towards more cinematic fights, Blue Dragon features a simpler system that essentially offered a much prettier version of combat that had been perfected on 2D machines in the ‘90s.

Smart twists to the turn-based formula aim to make combat more interesting and strategic, and are largely successful. Characters can charge up their attacks and sacrifice placement in the turn order to power up their moves, while random encounters have been removed entirely with all enemies out in the field for you to see, manipulate or avoid.

The most interesting of these options is manipulation thanks to the encounter circle, a ring that appears around the player that can be used to gather the attention of multiple enemies. If you draw multiple foes into the encounter ring and trigger a battle, enemies will fight among themselves, essentially turning what would be another fairly dry battle into something far more interesting. Dragging multiple groups of enemies into a battle is one of Blue Dragon’s greatest delights; you feel like a tactical mastermind as enemies kill each other and you mop up the scraps, and engaging in multi-battles even hands over generous additional rewards and boosts.

The rest is the JRPG norm, with magic attacks and the titular Blue Dragon as one of several allied creatures that shadows each cast member and offers them their powers. It’s all topped off with an equally traditional class mechanic that determines what skills each of your party members can use. There’s a lot of choice to be had in terms of building a unique group of characters with an approach to combat that’ll suit you.

It’s all solid stuff, and though it does become a tad too easy, Blue Dragon’s battle system is a real charmer. It’s a relic of a bygone age, just a lot prettier and flashier – but that’s no bad thing. I’d call it more respectfully reverent to the past than outright dated.

Sakaguchi’s story treatment keeps things simple and stereotypical. You take on the role of Shu, an archetypal spiky-haired lad whose catchphrase is “I won’t give up!”. Shu is joined by a cast of friends that each ticks a bunch of anime and JRPG checkboxes. As with the combat, Blue Dragon’s story feels like a greatest hits package of the JRPG genre in general. It’s not a sweeping drama but what you get instead is an adventurous romp that feels a little like you’ve stumbled into a Saturday-morning cartoon. It makes sense that Blue Dragon was adapted into two full seasons of anime on TV in Japan.

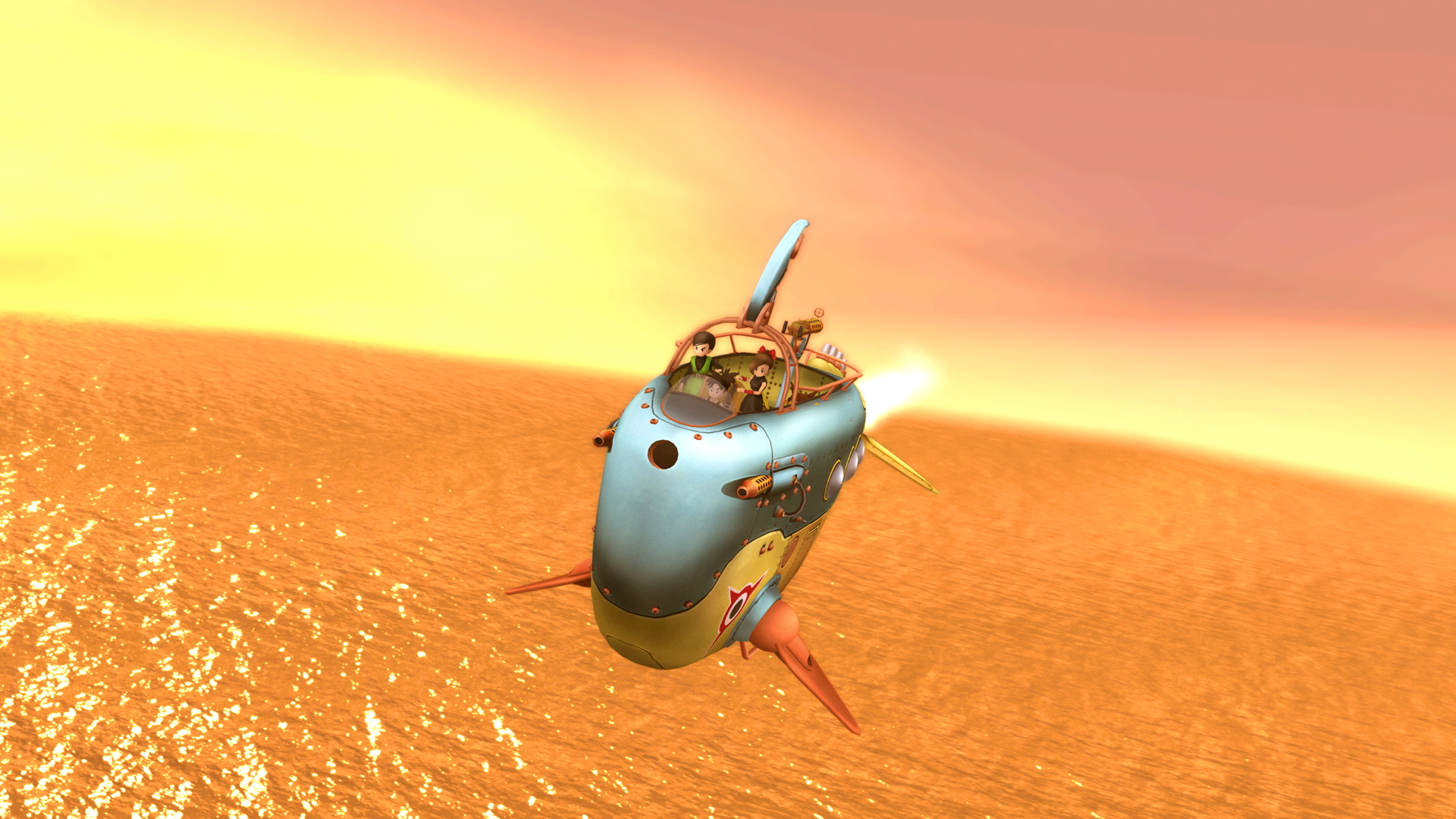

Combat is where Blue Dragon’s heart lies, but players are also treated to a charming onslaught of gorgeous visuals and wonderful world design. This is where the game is at its absolute best: from landshark-plagued deserts to icy mountains and perilous dungeons, it’s all a treat to look at. While now it’s quite obviously a game from 2006, I still feel it looks pretty good thanks to its crisp artwork and use of bright colours.

The visual splendour is underpinned by the wonderful musical score of Uematsu. The sweeping orchestral work offered here is up to his highly renowned standard and is the perfect complement for the visuals, at once moving and whimsical to match the game’s melodramatic plotting and breezy sense of humour. There’s also some fantastic and energetic synth-rock that matches the game’s exaggerated vibrancy.

The highlight of the score is a perfect example of what happens when you pair Microsoft’s first-party cash with the mad excesses of Japanese development. Blue Dragon features Ian Gillan of classic rock outfit Deep Purple, screeching out a series of nonsensical lyrics penned by Sakaguchi himself. For Gillan it was no doubt a solid payday, but the end result is one of the most gleefully mad, slightly bad and completely memorable boss themes in the history of Xbox – if not all video games.

Blue Dragon’s legacy is strong. It provided a platform for Sakaguchi to helm another big-budget RPG after his disastrous attempt at filmmaking, and marked Microsoft’s claim on the Japanese market. While the Xbox 360 ultimately didn’t find success in Japan, this, alongside Lost Odyssey and other games, serves as proof that Microsoft gave it a damn good try. Blue Dragon was the first Xbox 360 JRPG to matter, laying the groundwork for several others like it and allowing the console to sell far more in Japan than anyone anticipated. In this regard this tale of stereotypically spunky heroes is a truly special title in Xbox history.

While by no means a perfect game, in general Blue Dragon’s greatest flaw is one that proved difficult to look past on its initial release. The game is a slow mover by design but was made even more so by significant performance problems throughout. Slowdown in turn-based combat seems like a bit of a mad concept, but there it was: rearing its head frequently and seemingly at random.

It’s here where Xbox 360 backwards compatibility for Xbox One is something of a marvel. The fact that games work is impressive enough, but Blue Dragon impresses further: it’s vastly improved. It loads faster, and battles that would hitch and drop to 20 frames per second before now run at a near-solid 30.

In this, one of the game’s greatest enemies has been slain. Here, on Xbox One, Blue Dragon has a much deserved second chance to charm a new audience without the chugging performance. It’s a fascinating game; the most traditional of JRPGs to ever grace an Xbox platform. The game’s second chance is well deserved.

This article originally appeared in Xbox: The Official Magazine. For more great Xbox coverage, you can subscribe here.