By trading power and responsibility for failure and immaturity, Spider-Man: Homecoming delivers a perfect (origin-free) origin story

The MCU's latest doesn't need to show its hero's backstory. His present-day struggles tell us more than enough.

Spoiler warning: This article contains detailed discussion of the entirety of Spider-Man: Homecoming's story. If you haven't seen the movie yet, you might want to steer away.

It was often espoused before the film’s release – not least by myself – that one of the most exciting elements of Spider-Man: Homecoming was the fact that it wasn’t going to be an origin story. The narrative-stalling blight of superhero movies, the background-filling origin tale is (usually) a clunky nightmare of a thing. It’s obliged to be there just in case there’s a single member of the audience wondering, say, what Batman’s parents think of his night job, but it’s utterly pointless to anyone else, doing little but devour valuable running time that could otherwise be used for, you know, actually telling a story.

Effectively, origin stories reduce most franchise-starting cape capers to the state of a condensed half-movie, prefaced with a lengthy ‘Previously, on things you’ve known since you were ten’ recap. In the case of Spider-Man, who has had his origin depicted on-screen twice in 15 years, walking into the cinema to discover the opening reel of another retread would have been grounds for arson. Or at least turning up half an hour late.

So hurrah. No origin story in Spider-Man: Homecoming, then. Everyone rejoice. Except that actually, the entire film is an origin story. It might skip all the traditional trappings of the tired old trope – there’s no gaining of powers, no discovery of abilities leading into an awkward training montage, and there’s certainly no costume-designing. Homecoming might start well into Spidey’s career – he’s been active since a good while before Captain America: Civil War, and has already integrated superheroism into his day-to-day life - but it’s absolutely an origin story. In fact It’s the best origin story in the MCU, because it’s the only one that skips all the pace-killing narrative logistics and obligatory background explanations, and simply relates the core, emotional essence of a superhero’s early days by adhering to the fundamental storytelling rule of ‘Show, don’t tell’.

We get one precisely token reference to the source of Peter’s powers. It comes relatively late in the film, is over in a couple of seconds, and exists only as the latest part of an organic running joke regarding his best friend Ned’s endless curiosity. It also sums up the film’s whole approach. Homecoming is far more concerned with genuine character and relationship-driven storytelling than mechanically ticking the boxes of How Superhero Movies Work. If one or two of those boxes get ticked by accident along the way, fine, but they’re not the priority.

Origins and learnings

Where things get more clever is in the way that Homecoming then uses the extra space freed up by jettisoning the unnecessary origin baggage to tell a complete, fully realised story, but infuses it with heroic origin subtext in an entirely ambient way. In a more pervasive, affecting, slow-burn fashion than it ever could by explaining things in rote, explicit terms. In Spider-Man: Homecoming, Peter Parker is simply Spider-Man. He already knows what he can do. He’s already pretty confident about it. He already spends every spare moment on the job, righting wrongs and doing good wherever and whenever he possibly can. But most importantly, from Homecoming’s start to its thematically brilliant finish, he’s also really, really crap at it.

He’s eager to fight crime, but crap at finding any actual crime to fight. When he does find crime, he’s often crap at chasing it. He’s crap at understanding his limitations, and forgets that he can’t very well be Spider-Man when there are no tall buildings or ceilings to use. When he gets to the top of somewhere really tall, he’s also crap at dealing with vertigo. He’s also crap at knowing the strength limitations of his webbing, crap at realising when he’s over-stretching himself, and not entirely brilliant at fighting bad guys either. Even the common-or-garden, street level goons that even Hawkeye could drop. He’s crap at using his new suit, really crap at interrogating people, and most importantly of all, crap at realising that he’s crap.

Sign up to the SFX Newsletter

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Among all of the other origin tropes that Homecoming chooses to ignore, it’s perhaps most notable that the film eschews any hint of the iconic “With great power comes great responsibility” moment. In Homecoming’s more grounded, emotionally realistic world, Peter’s motivations for superheroic growth are entirely different from his traditional desire to empower himself as a personally driven bastion of Right. He’s a kid who grew up as a superhero fanboy, accidentally found that he might have a chance of living his childhood dream, and then somewhat childishly set about trying to realise it.

He was ten years old when the Avengers saved New York. He was six when Tony Stark first became Iron Man. He’s always lived in a world where superheroes were the norm. To him, fighting crime in a cool costume probably holds the same superficial aspirational value as becoming a pop star. He has a good, caring nature, but there’s no real question of power and responsibility because - in a world where the Avengers have been protecting the world for half a decade as a group, and longer individually - a 15 year-old kid from Queens isn’t responsible for anything, and certainly has no power.

Embracing failure

Spider-Man: Homecoming steers into that. It steers into it constantly. But smartly, it does so while masking Peter’s repeat failings – thereby maintaining his winsome likability – by couching them in the entirely believable, relatable, and completely natural failings (and successes) of being a kid. The everyday ups and downs of Peter’s school life – for him and his friends - aren’t simply a distraction. They’re the character-building foundation that makes the rollercoaster of his costumed life totally justifiable on a personal level. We never get angry with him for screwing up, because we know why he’s screwing up. He’s 15. He’s believably 15, and when you’re 15, screwing up is a large part of what you do.

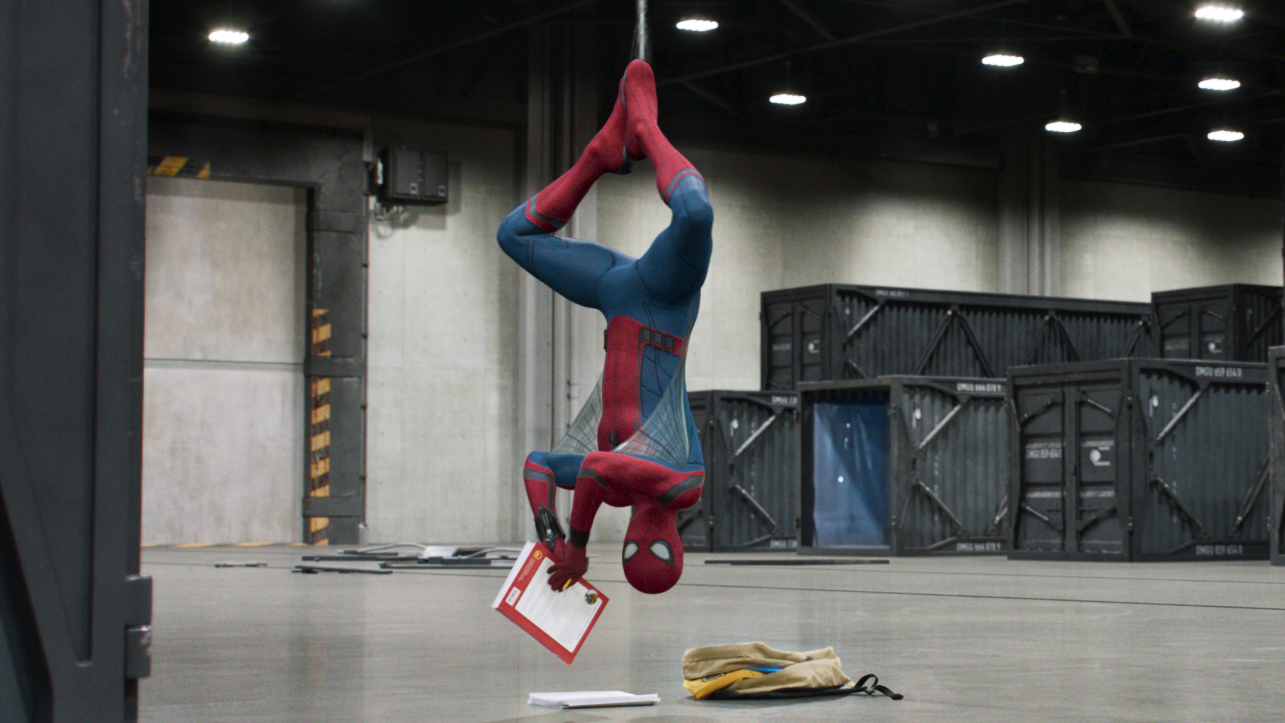

This gives Homecoming the facility to build its grandest moments around failure rather than heroism. Think about the stand-out scenes that drive the movie’s plot. There’s Peter’s mission to intercept the would-be hijack of a truck full of Chitauri technology. In any other film, this would have been a defining, mid-scale victory, spurring him on in heroic confidence. In Homecoming, Peter messes up, and finds himself locked in a warehouse overnight, from which he’s powerless to escape except by the lamest, most brute-force of methods.

There’s the ferry scene, which should be a crowning moment of set-piece badassery, the moment at which Spider-Man truly arrives in New York and becomes its adopted mascot hero. Instead, it turns into Peter attempting to rescue people from a disaster of his own making, before eventually having to be rescued himself. By his mentor, humiliatingly enough. On a smaller scale, but even more impactful, there’s the car scene before the Homecoming dance, where the Vulture, unmasked and in his day-to-day guise as Peter’s girlfriend’s dad, bullies the would-be hero into submission.

This isn’t just about villainous threat. It’s another brutal reminder of Peter’s childish inexperience. The genius reveal of the Vulture’s homelife reality comes will all kinds of additional dramatic heft beyond the expected awkwardness in relationship dynamics. The Vulture is no longer just a bad guy for Spider-Man to fight. He’s a real, tangible adult. A parent. The parent of a girlfriend. The final boss of the authority gauntlet in Peter Parker’s civilian, teenage life. And Peter crumbles. Because of course he does. The subject of the conversation might be villainy and murder, but it’s also, just as significantly, about a kid being intimidated by a grown-up.

And then there’s the other warehouse scene, toward the end, when Peter’s cocky inexperience sees him buried under tons of rubble and unable to act. He’s not Spider-Man at this point. He’s a scared child, dying and close to tears, overwhelmed by an unforeseen situation as heavy as the concrete involved. He transitions from wannabe-hero to desperate victim, crying out for help just like those he dreams of helping himself. Crying out for the assistance of someone better than him. For the help of a real superhero.

It’s only when he sees his reflection blended with his fallen mask that he remembers that such behaviour isn’t good enough, but again, there’s a neat contextual subversion here. In Homecoming, this realisation isn’t an empowering, third-act affirmation of who he really is, as would be depicted elsewhere. It’s Peter remembering who he’s trying to be, and making perhaps his first real effort to earn that status.

Victory from the jaws of defeat

Homecoming’s final stretch hammers this stuff home wonderfully. It’s easy to miss, but despite Peter’s valiant battle atop the Avengers’ stealth plane, this might be the first mainstream superhero movie where the hero doesn’t actually defeat the bad guy at all. The Vulture is eventually scuppered by his own equipment’s technical failings, and Peter is just there when it happens, trying and – finally – succeeding in saving him. And then, ultimately, there’s Spider-Man’s abortive induction into the Avengers, which Peter turns down. A nice moment of modesty on the surface of things, but as the moment that rounds off Homecoming’s epic journey of well-meaning failure, it’s the most truly heroic set-piece in the movie.

Because this isn’t a film about a burgeoning superhero finding inner strength amid adversity, and graduating to greatness. It’s a film about a wannabe hero realising that his strength is still lacking, amid a great deal of getting his ass kicked – not least by himself – and admitting that he’s just not good enough yet and has more to learn. And - as in superheroism, as in life - at various stages that’s the truest origin story of all.