Six years after its release, is Catherine a sexist nightmare or feminist parable?

2011's platform puzzler deserves a second look for tackling challenging themes that most games daren't tackle

If video games were a physical realm, it would be a hostile and potentially lethal place for women. This is an industry where female bloggers and developers regularly receive death threats, where female gamers are jeered online simply for their gender, and where it’s still hard to find a female character who is validated for anything beyond sexuality or physical attributes. Misogyny, it seems, is still the flavour of the day.

Catherine is a game that appears to feed into all the tropes women have been fighting: woman as sex object, nagging shrew and beastly bitch. The game begins with our hapless protagonist Vincent, a slacker journalist who has been suffering from recurring nightmares of being transformed into a sheep and forced to climb crumbling structures to avoid falling to his death.

In the real world, things are just as fragile: Vincent’s girlfriend, the sensible-if-stern Katherine, thinks it’s time to get serious and settle down. How boring, and restrictive! Vincent spends his time lamenting this turn of events with his friends in a smoky bar, until one night he meets the gorgeous and voluptuous Catherine, and starts sleeping with her on the sly.

When Catherine was released in 2011, first in Japan and America, then in Europe a year later, the overall reaction was positive. Critics praised its fiendishly difficult platform puzzles and nightmarish imagery yet didn’t think to unpick the gender politics at play or challenge the way women were depicted. A critic for the Guardian applauded it for exploring the complexities of love while IGN described Katherine as the typical nagging girlfriend and Eurogamer conjured her visage in Vincent’s nightmares as a “razor-toothed crotch-maw”. It probably won’t come as much of a surprise that these critics were also male.

A sleazy exterior belies mature themes

Neither should it come as a surprise that most of Catherine’s promotional material was obviously intended for the male gaze. One of the most recognisable shots (pictured above) zooms in on Catherine’s head and torso as the character reveals her ample cleavage and smiles coyly at the viewer. Other pictures look like screenshots from a hentai film: one where Vincent’s head is caught between Catherine’s spread legs is particularly suggestive; others where Catherine is on her back or side look as carefully arranged as a Playboy Bunny centrefold.

If salivating males were Atlus’ designated audience, the developer did very well. But there are other reasons to play Catherine, too. Despite its oily sheen of sleaze, the game is genuinely gorgeous to interact with. The title screen, for example, sees Vincent dangling from a ledge, screaming Katherine’s name against a fuschia backdrop, while she stares past him nonchalantly. The rest of the game fizzes with these pink-and-black strobes of colour. The plush café Vincent frequents with Katherine is sweetly decorated in pale pink (a suggestion that Katherine is smothering him with love?) while the netherworld Vincent finds himself in every night is as black as an abyss.

Such a bold visual palette suits the plot perfectly. Like a soap opera played out in the style of an anime, Vincent’s love triangle is told through a variety of cutscenes where Vincent meets Katherine, hangs out with his friends in a bar called The Stray Sheep and has sex with Catherine in his apartment. In a nifty touch, you can walk around The Stray Sheep, interacting with customers and answering texts. Most of these come from Katherine, who either berates Vincent or lets glimpses of vulnerability slip. Each text is accompanied by the sound of a small, feminine sigh: a more potent method of expressing quiet disappointment than words could ever achieve.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

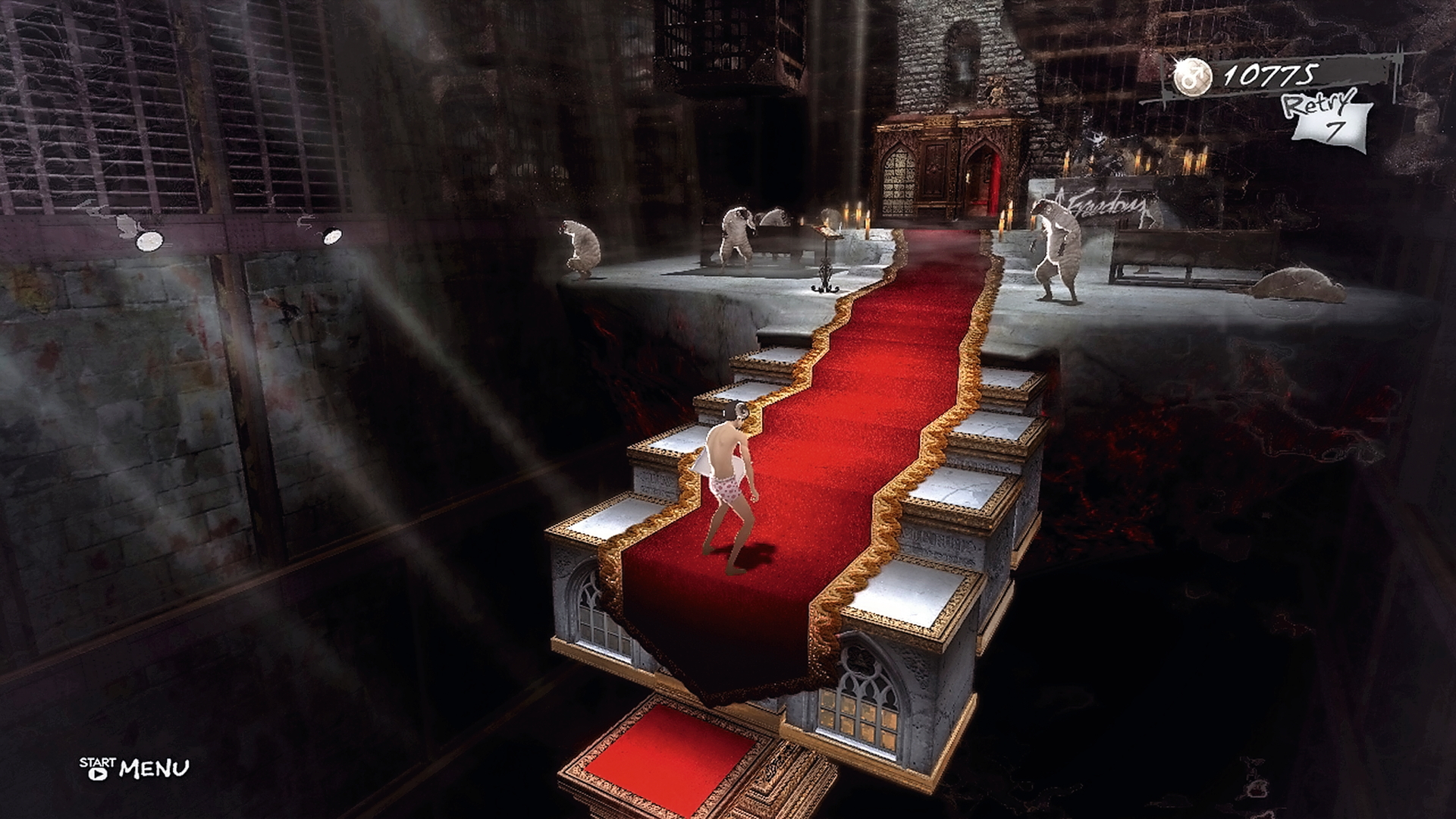

The majority of Catherine, however, takes place in nightmare, where the player must solve increasingly difficult platform puzzles in order to survive. Each level is divided into three stages, and each one is trickier than the last. What starts off as simply climbing a tower and strategically moving blocks around, becomes impossibly hard. As levels progress, boxes can fall on you, spikes pierce you if you step on the wrong block and other men trapped in the pit push you off the edge.

If it sounds repetitive, it is, but the mechanics are elevated by the game’s imagery. The netherworld plays upon the essence of limbo: of repeating a set of trials for all eternity or being lost forever. Each level also ends with a monster, which clambers after you as you feverishly try to get away. Some of these creatures are deliciously hideous, such as a posterior with eyes and a tongue that emits heart mist as breath. Then there’s the church confessional, where a mysterious, omniscient voice calls to Vincent. Calling him a little lamb, the voice asks Vincent sly questions on sexuality, marriage and morality. It’s curious, as you’re never sure whether you’re answering as Vincent or as yourself.

If Catherine achieves one thing, it’s that masculinity has never looked so fragile. Character designer Shigenori Soejima based Vincent’s look on Buffalo ‘66 director Vincent Gallo, but any resemblance is purely artificial. Unlike Gallo’s smoky arrogance and dark good looks, Vincent is a puddle of nerves: shaking, shivering and constantly doubting himself. Women are often criticised for having no agency, but here the stereotype is reversed. Vincent doesn’t take any responsibility for his actions, saying Catherine “forced herself on him” and that “he had nothing to do with it” after they sleep together. He’s such a limp noodle, it’s sometimes cathartic just to watch him die.

The game's big 'twist' polarised the audience

Despite the wet puppy protagonist, director Katsura Hashino should be commended for tackling subjects most video games wouldn’t. The game examines the morality of cheating, and how hard it is to be an adult. Vincent feels stuck, not just in his relationship but his career; his friends act like overgrown teens, and he goes to the same bar every night. The two women come to represent two halves of Vincent: the piece that wants reliability and one that wants to be young and unfettered forever.

The game would have felt more mature, though, if it didn’t boil women down into their most basic stereotypes. Katherine is the girlfriend we all fear: beautiful but frightening, constantly appraising Vincent with a cool, dissecting gaze and picking apart everything he does. In Vincent’s nightmares, she only becomes worse. One scene sees her transform into a pair of giant, gnarled hands that have the power to obliterate Vincent into a puddle of bones and blood if they stab him with a fork. Katherine isn’t a woman, she’s responsibility, and it’s not too hard to see that with a serious relationship comes death.

In contrast, Catherine is the object of desire. She’s queasily attractive, with the face of a china doll and the body of a bodacious woman. There’s a juvenile element to her, too: clad in knee socks and a ribbon tied around her waist. Her body is a dream, but so is her outlook. The first night she meets Vincent, she says to him, “who wants to be tied down anyway?” She’s too good to be true. Except the big revelation is that Catherine isn’t a woman but a succubus: a demon that preys upon men and seduces them by becoming their deepest desire.

Players asked, ‘doesn’t this make Catherine the most feminist game of all time?’ She takes cheating men and punishes them. Not exactly. It then turns out Catherine is just working for an ancient Sumerian demigod called Dumuzid, who hurts men for not procreating. This just makes Catherine even more of a subservient character: not only is she turning herself into what men want, she’s also doing it on the orders of another man.

Why did Slate magazine call it the 'most sexist game of all time?'

When female players did begin to question the way women were portrayed, the reaction from men was vehement and occasionally toxic. “Women typically hate video games because it takes them away from men,” one wrote on a forum. “They hate men who don’t obsess over and serve them.” Ouch. Another wrote that “Catherine just makes me hate women.” Although Hashino wanted to make a complex game with mature themes, it seems the message was black and white for most players.

It would be easy then to look at the sexism that streaks through Catherine. But the game plays much more upon gynephobia, which is the fear of women. Portraying both women as monsters may be heavy-handed but it’s effective, and the message is even clearer: women want to devour men, and they won’t rest until they’ve ensnared them. It’s a game where comments about sleeping with women and throwing them away ebb into darker ones like, “you’ll never know when they’re going to stab you in the back”. This fear seeps into other characters, such as trans woman Erica, who is only in the game to tick a fetish box; all she does is flirt with the boys and offer to wear stilettos.

In the end, an outcome out of six possible ones awaits you. You can choose to settle down with Katherine, go solo or be with Catherine. If the latter is your ending, you may become a demon and have as many succubi tending to your sexual needs as you’d ever want. As a bonus, if you complete the game on the hardest mode, the goddess of love, Ishtar, will turn you into a god and have sex with you. What more could you ever want?

Since its release, people have been more critical of Catherine. Although it’s a striking game that tackles brave topics, such as infidelity and fears of settling down, publications like Slate have written articles calling it the most sexist game of all time. And there is truth to that. Catherine isn’t afraid to take the worst female stereotypes and milk them until only the barest silhouettes remain. Perhaps the opening paragraph of this piece should be amended: If video games were a physical realm, women would be welcome, but only if they were subservient and do everything that men want.

This article originally appeared in Xbox: The Official Magazine. For more great Xbox coverage, you can subscribe here.

Kimberley Ballard is the former Production Editor of SFX, T3, and Official Xbox Magazine, and was once the Communications Manager of Future Plc. Kimberly left the business in 2020 to pursue a job in the video game industry; she is currently stationed at Creative Assembly, where she works as an Associate Brand Manager for the Total War series.