That Console Feeling: What defines console gaming in 2015?

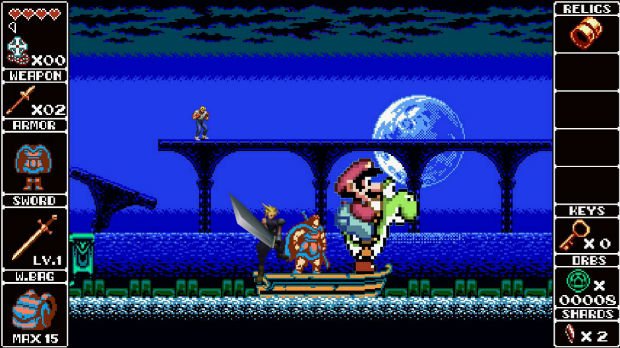

For the old school console fan, 2015 is a paradise of fresh delights. Axiom Verge oozes that classic console feeling when it starts up on PlayStation 4. The grinding wub-wub-wub of the distortion field weapon and its glitchy effects warping the blocky environment seem like they were lifted right out of 1989. The same is true of The Adventures of Pip. Played on a Wii U, the hero’s transformation from single block into increasingly detailed pixel dudes is practically a greatest hits tour through the transitions in tech from Atari 2600 to NES to SNES. Odallus even has those fetching scan lines right on the screen to mimic sitting in front of a CRT television. “Wait a second,” mutters the console purist, gently setting down her Jaguar controller. “Odallus is a PC game!”

JoyMasher’s game only looks like a console game. Axiom Verve and Pip, despite being readily available on those slick little boxes with controllers that never need a keyboard and mouse to operate, also happen to be playable on PC. These games may have been made to ape the ticks and charms that made console games so distinct from their PC cousins in the past, but in 2015 there are almost no tactile differences between games built on any platform. If the specific pleasure of firing up and playing a console game is ubiquitous across all platforms, what defines console gaming now?

Understanding just how incredibly different console games were to one another in their heyday is difficult in an era when XCOM: Enemy Unknown runs as comfortably on a PC and iPad as it does on an Xbox 360. It wasn’t just that each machine had its own style of controller, either; even the noises they made were particular. Consider Sega and Nintendo’s 16-bit beasts. Genesis does indeed do what Nintendon’t but the reverse is equally true. Super Nintendo games used a custom built processor called the S-SMP to generate sound effects and music, resulting in tones with a characteristic warmth. Think about the smooth horn blats of the Super Mario World soundtrack (and the admittedly farty noise made when Mario enters a Koopa castle) for perfect examples of that machine’s audio identity. Sega’s Genesis used a stock sound processor, the Yamaha YM2612. While just as capable of making some bitchin’ tunes, the YM2612 produced a drier, almost acidic tone encapsulated by bruisers like the Streets of Rage 2 soundtrack. Compare the main theme of Chrono Trigger remixed using Genesis sounds compared to the SNES original.

The specificity of the hardware, like the SNES’ custom sound chip and the fact that consoles couldn’t be gradually augmented with more memory made game development on those consoles isolated, but also focused. PlayStation developers had an easier time making 3D games because that console’s processing power wasn’t awkwardly spread out across multiple processors like the Sega Saturn. For 2D games, though, Saturn trounced the PlayStation because of the lack of video RAM in Sony’s box. The differences between those two platforms made the same game feel different depending on where it showed up. Resident Evil’s Jill Valentine is jagged on PS1 but more detailed compared to the smooth, simple character model on Saturn.

Every console had its own quirks, its own identity as well as flow in its games that culminated not just in a house style but also a genuine hominess. Recognizing the instrumentation and sound libraries cohere across multiple Super Nintendo games like Chrono Trigger and Secret of Mana let the console itself grow deep roots in a regular player. For any ravenous fans of Capcom’s arcade work in the mid-’90s, the Sega Saturn’s 2D capabilities made it the only place to translate those brief experiences into something lasting at home. Even machines like the Nintendo 64 whose technical abilities seemed like drawbacks on paper could become benefits as you became attached to its specific style. Did the muddy textures and hazy resolution of N64 games make them immortal works of graphical achievement? Hell no, but for the people that love that machine in its games, that smudgy look is representative of everything great about the console. Consoles could have a style that was also a soul.

Games the cross between console and PC today are actually very capable of mimicking the particulars of classic machines like Super Nintendo, but those artful flourishes aren’t a result of using locked-in hardware specifications. Axiom Verge, whether played on a PS4 or a PC, feels like a modern successor to Nintendo’s own Super Metroid, from the chunky biological art design to Tom Happ’s eerie sci-fi music. Rather than milking a specific sound out of a custom chip, though, the soundtrack was made using an old version of SoundForge and Sonar X2. The game itself was built using software called MonoGame. The result is classic console style but what’s ultimately a device-agnostic feel; Axiom Verge was built with those tools precisely so it wouldn’t be confined to a single platform like old console games.

What marks a console game today actually has nothing to do with what’s in the games, but the ecosystem that surrounds them. Each console environment gets its shape in multiple ways. One aspect is the online community. While cross-platform play between PC and console games like the kind Capcom’s building for Street Fighter V is becoming more common, the player pools on PlayStation Network and Xbox Live do remain largely closed and specific. Multiplayer communities, achievements, trophies, and just the simple notifications that someone you know has been playing the same things you have creates a sense of shared experience that gives that specific console a new feel and form.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

While the technical proficiencies of the consoles don’t necessarily define their games anymore, what the makers of those consoles choose to fund and create also internally further shapes the culture of that machine. Nintendo and its fleet of mascots are the most obvious example. Modestly powered PCs could run games like Super Mario 3D World without much difficulty – Wii U uses a PowerPC processor not dissimilar to the PC-like Xbox 360 – but that game and others published by Nintendo share. Wii U games tend to be colorful and emphasize action over story; even games made by studios outside Nintendo’s offices like Bayonetta 2 share that spirit.

Less specific than Nintendo, Sony and Microsoft nonetheless have their own content cultures. Sony, for example, has been cultivating the same persona since it got in the game back in the ‘90s. Its publishing slate tends to mix blockbuster savvy with a flair for quiet, weird experimentation. That’s how you have Uncharted coming out of the same pool as Tokyo Jungle and The Puppeteer with a heavy emphasis on individual characters and largely single-player experiences. Microsoft on the other hand has always banked first on big, blockbuster style games that emphasize multiplayer. Halo, Gears of War, and the Driveatar-ridden roadways of modern Forza all have ample space to play by yourself, but they’re sold first as things to play with other people. (It’s hard to find an Xbox One tentpole that doesn’t have four-player co-op.)

For the old school fan, longing for those aesthetic quirks that made console gaming so distinct in the 20th and early 21st century, your options are limited. There’s always the hardcore homebrew scene, where people are even still cranking ZX Spectrum games alongside new NES and even SNES games. They can satisfy, but it’s no easy task to find homemade games that feel as polished as the classics. Games like Axiom and Odallus that pay homage to an era of more specific technology scratch part of the itch, but even games as precise as those aren’t wholly the real deal. Which is fine. It simply means that old console feeling is itself an antiquity, the soul of games as they were, not as they are.