The cost of dreaming big: a Lionhead retrospective

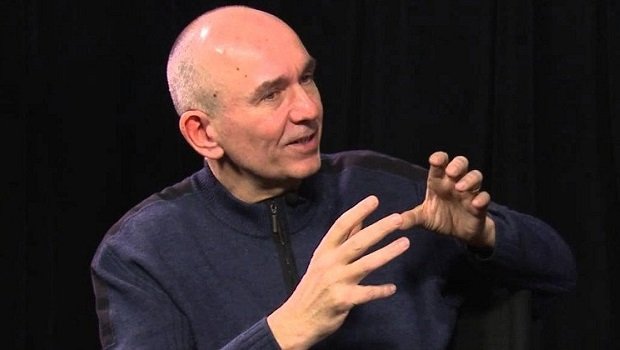

This week potentially marks the beginning of the end for Lionhead Studios, as Microsoft has cancelled the upcoming Fable Legends and "are in discussions with employees about the proposed closure" of the studio. Over two decades, Lionhead, originally helmed by visionary game designer and human embodiment of unbridled eagerness Peter Molyneux, has developed a number of incredible video games, often finding itself trying to punch through a wall formed out of its own lofty ambitions - ambitions that would simultaneously be its greatest asset and biggest curse.

Molyneux originally made a name for himself at his prior company, Bullfrog Productions, with the creation of Populous, largely cited as one of the first 'god games’. He and his studio would go on to design a string of highly-influential PC hits, with instant classics like Theme Park, Syndicate, Magic Carpet, and Dungeon Keeper being cranked out of the studio year after year, earning Molyneux a large following among the gaming public. Electronic Arts regularly published Bullfrog's games, and its success led the publisher to bring Molyneux on as its vice president in 1994 and acquiring his studio in 1995. Molyneux butted heads with higher ups over Dungeon Keeper's numerous delays and the overall culture that comes with working at the upper levels of a major video game publisher, eventually resigning from his position at EA to go independent once again, forming Lionhead Studios in 1996.

Lionhead wouldn't release its first game, Black & White, until 2001 - five years after the company's founding. Its release was somewhat poetic, as Molyneux's new studio brought with it a return to the genre that made him a household name among those tuned into the video game industry. Black & White makes you god of a cartoonish world, ruling over its diminutive denizens and a series of larger than life creatures, influencing their evolution over time based on your own good or evil actions. At the time, Black & White was incredibly well-received, seen as the rebirth of a genre that Molyneux had helped to create as well as an intricately designed "virtual toy", but public opinion soured over time, with publications like GameSpy deeming it "the most overrated game of all time". This, along with Lionhead's penchant for protracted development cycles, would become a narrative that would haunt Lionhead throughout its existence.

Then came Fable in 2004, the game that would, for better or worse, define Lionhead Studios for the rest of its existence. The hype surrounding Fable's release was legendary, with Molyneux rattling off idealistic promises about how the world and its inhabitants would buckle under the weight of your choices; about how an acorn that falls off a tree will plant another tree beside it; how that tree would then grow over time; about how you could get married and have kids and how those choices would have consequences that affect the game's story. What we got, however, was an above-average action-RPG with a rote, by-the-numbers narrative and some cheeky emotes. Some of your choices had consequences, but they were all telegraphed from a mile away (do you choose the good version of the quest, or the evil version?) and the biggest promises - acorns, children, and so on - never came to fruition.

It's not that Molyneux lied about these features, exactly - according to a post from Molyneux on Lionhead's old forums, in many cases they had been coded and completed early in development. But for whatever reason, whether it's because allowing for realistic tree growth took up 15% of the Xbox's processing power, or that the promised features ultimately didn't fit with everything else, much of Molyneux's ambition had to be curbed due to the realities of game development. Thus began a strange relationship between Peter Molyneux and the public, who would continue to make the same mistakes year after year - building up hype to a fever pitch and then watching as that hype deflated like a balloon when the finished product failed to live up to Molyneux's elevated and often unrealistic expectations.

It's hard to say whether the collective come-down from Fable caused Lionhead's next few projects to falter, but the years immediately following its release weren't exactly kind to the studio. The Movies released in 2005 after four years of development, casting players as the head of a budding Hollywood movie studio starting out in the silent film era, and allowing them to hire actors, upgrade their studio's film technology as they progress through time, and actually make their own movies and upload them on the internet. It was an ambitious, if ultimately flawed, game that failed to make a commercial splash, causing publisher Activision to cancel the planned console versions due to poor sales of the PC version. Black & White 2 similarly flopped, failing to capture the imaginations of critics and audiences like the first game did. Despite this, Fable's runaway success inspired Microsoft to swoop in and acquire the studio in 2006, as the multimedia behemoth attempted to expand its first-party library for the newly-launched Xbox 360 console.

Fable 2 launched in 2008, three years into the Xbox 360's lifecycle and four years after the release of the first game. While the series would likely never quite live up to the vision as originally described by Molyneux, Fable 2 is perhaps the closest it would ever get, featuring online co-op, a unique navigation system that dropped a mini-map in exchange for a breadcrumb trail of glowing dots, the ability to have children, and a larger array of side-quests, mini-games, and cheeky emotes. It would go on to be a critical hit as well as one of the best-selling RPGs on the Xbox 360, with over 3.5 million copies sold by 2010. It also features a story described by Peter Molyneux as "rubbish", as he continued to beat himself up over his inability to design a game that lived up to the version that existed in his head.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

In between the games it actually released, Lionhead would plug away at equally ambitious experiments that never quite panned out. There was BC, in development for the original Xbox by Intrepid Computer entertainment, a satellite studio of Lionhead, which would have been a massive open-world set in prehistoric times in which players would need to scour the land to build tools and weapons to grow their tribe and fight deadly beasts. It was cancelled for mysterious reasons, a simple quote from Molyneux on the developer's (now defunct) website stating that he "[hopes] to revive the project at a later date". Then there was Project Milo, an impossibly ambitious title that would have allowed players to interact with a virtual young boy. You would play games with him, talk with him about things, and watch him grow, all through the magic of the Xbox Kinect. It sounds too good to be true, especially on the admittedly limited tech behind the Xbox 360 and Kinect - Microsoft has gone on record stating it was "never really a product", despite Molyneux's insistence to the contrary. It's not known exactly how much of its demos were actual gameplay or a liberal application of digital smoke and mirrors, but it's existence is the embodiment of Molyneux's work at Lionhead: always reaching for the stars, but forever coming up a little bit short.

Molyneux's last game with Lionhead as creative lead would be the ill-fated Fable 3. Coming four years after the previous entry, Molyneux sought to shake things up by simplifying combat to engage a wider audience, as well as asking players how they would rule a nation as its monarch. All of this sounds great in theory, but the game was riddled with technical issues, its combat perhaps too simple to be properly engaging, and its final third funnels you through your time as Albion's ruler like an overly-eager child tugging on your arm, quickly pulling you through a theme park attraction without giving you any time to enjoy it. Ever the self-deprecator, Molyneux described the game as a "trainwreck" - perhaps a bit of a harsh description for a game that ultimately turned out fine, but for Molyneux, 'fine' is clearly never good enough.

Since Fable 3's less-than-stellar reception, the series found itself on a downward spiral, leading to mediocre spin-offs like the "not on rails" rail-shooter Fable: The Journey and the lackluster beat 'em up Fable Heroes. Molyneux left Lionhead on March 7, 2012 to "become an independent developer again", forming 22Cans with other ex-Lionhead employees. While Molyneux was off designing his weird iOS experiment with its "life-changing" prize (and embarking on a whole new series of bizarre missteps and gaffes), Lionhead was sort of left in a lurch. With its lead visionary gone, the studio released Fable Anniversary, an Xbox 360 update of the original Fable, and began work on Fable Legends, a four-on-one multiplayer game that failed to garner any real buzz - a game that would be cancelled before it ever made it out of closed beta.

And so the story of a studio borne from a desire to create experiences that allowed for an unprecedented level of player choice and consequence, of a studio meant to continue Peter Molyneux's game design legacy, is left up in the air, a potential closure looming over it like a dark cloud. But while Lionhead may not conjure up the same level of fondness as Molyneux's previous work for Bullfrog, its body of work stands as both an inspiration and a cautionary tale on the costs and realities of dreaming big. Lionhead's games may not have been perfect, but they at least aspired to be something more than what they were, and the path it took over the last two decades may have been rocky, but it was rarely ever boring.