GamesRadar+ Verdict

Kojima’s mysterious would be epic has its moments but can’t carry the weight of expectation.

Pros

- +

An incredible visual achievement

- +

An atmospheric world

Cons

- -

Tedious core mechanic

- -

Little threat or risk

Why you can trust GamesRadar+

After all the conspiracy theories, conjecture and just plain hype, Death Stranding turns out to be about carrying boxes from A to B. And, often, back again. That’s it. That’s the game. This is going to be a spoiler free review in terms of story, but mechanically it’s hard to talk about anything without making it clear: you carry boxes around pretty much the entire time. Sometimes you fall over, occasionally ghosts appear and get in the way, but otherwise almost the entirety of your time involves staggering over uneven terrain carrying a backpack loaded to spine-rupturing levels with anything from underpants to medical supplies.

Extinction event

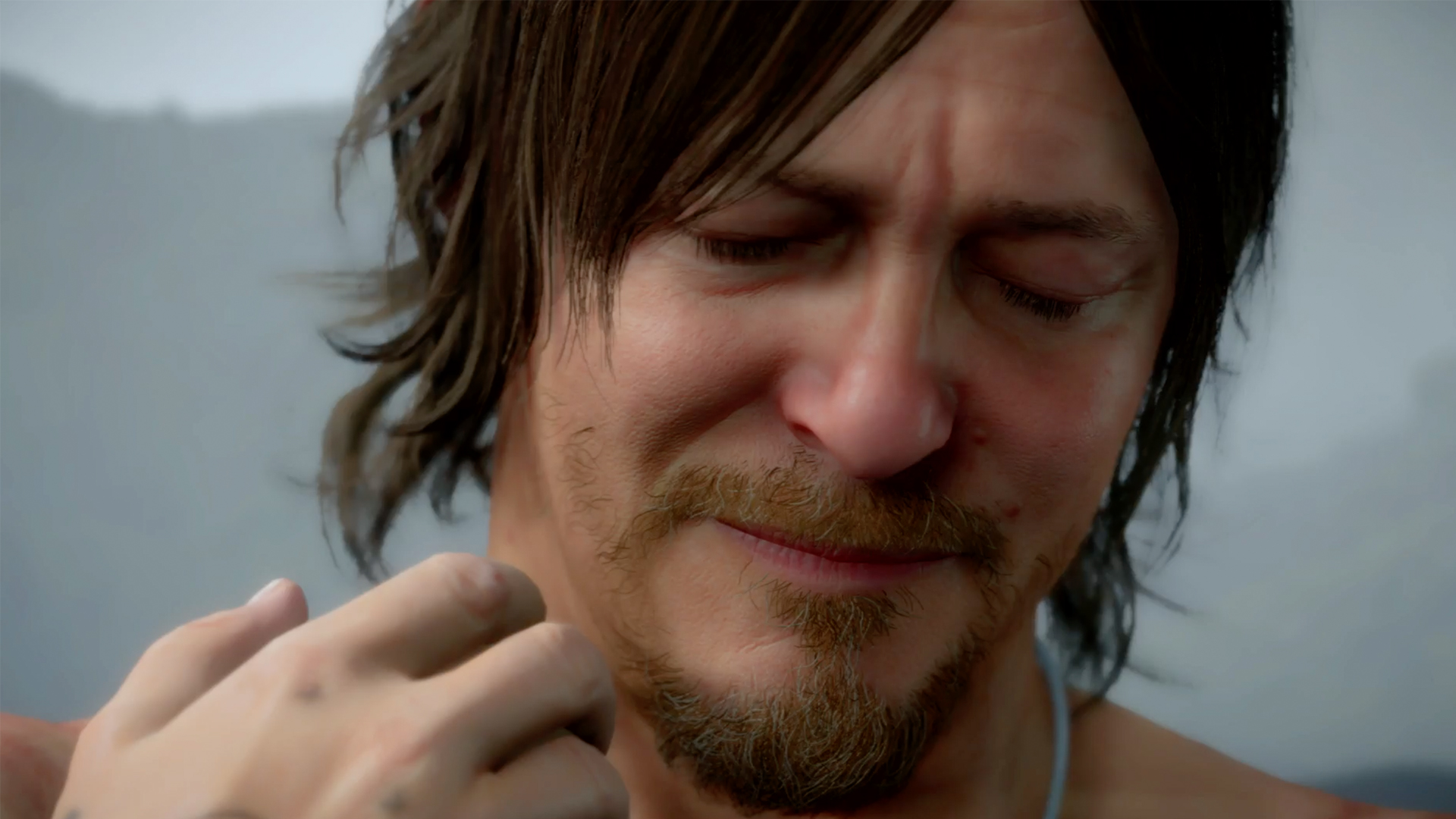

The idea is that ‘the Death Stranding’, a cataclysmic past apocalyptic event, has reduced the world to little more than walled cities and bunkered survivors, known as preppers. The outside world is a rocky hellscape filled with ageing Timefall rain showers and Beached Things, or BTs – spirits of the dead unable to pass on, and now drifting the wasteland fatally seeking out the living. Even now, after some 70-odd hours of playing, it still sounds exciting, and the first time you encounter these ethereal spectres, tethered to the world by a ghostly umbilical cord, there are shivers. At the front end there’s an exciting prospect laid out in front of you: it looks incredible, with a beautiful landscape you can endlessly drink in, and some incredible facial capture (one late scene contains some of the best in-game performance I’ve ever seen, that’s almost impossible to distinguish from someone just being filmed). The world, the idea, and the promise looms large.

And so you set off, carrying your boxes full of stuff to wherever you’re meant to go. And you carry, and you carry. Sometimes you fall over. Sometimes you creep through fields of somnolent, shadowy wraiths, sometimes you get a moment of contemplative isolation over an amazing vista. Sometimes you fall over again. But as you deliver, and deliver, you start to realise that the mechanic of carrying things is almost the only way you can reach in and touch the world. In the same way that a shooter only really lets you interact with a game’s world through shooting things, Death Stranding principal form of interface is transportation.

It’s not a bad idea per se – there’s a contemplative element to loading up, choosing your gear and then setting out – but it’s basically all you do and there’s only so long that idea can be interesting. It’s a gameplay language with little vocabulary, so the experience struggles to express itself in any deep and meaningful way. Your cargo might be very fragile, or explosive, as a variation, or the ground might be extra rocky… but that’s about it. In the later stages of the story, when the stakes are raised, the only way Death Stranding’s gameplay can really express any sense of tension is by asking you to walk incredible distances or, in several ‘oh Jesus, really?!’ moments, ask you to walk back, or further, on completion. (There’s is eventually a fast travel system, but it only transports ‘you’ and no cargo.)

Fighting chance

There are moments of variation – some more traditional third person combat (again, seen in trailers) – but these are tangential, fleeting moments that feel like an addendum. Arguably show stopping moments but not really substantial enough to have any real impact. Even in these moments of direct conflict however there’s almost no real threat, and generally the worst that happens is damaging a package so much you fail the mission. There are a scattering of human enemies called Mules who, for reasons, are addicted to stealing cargo. They’re easy to Square button thump into submission though, even before you unlock any weapons, and even easier to avoid. Even the BTs, the poster monsters for the whole thing, aren’t particularly dangerous. They’ve easy to avoid, and even if you do get ‘caught’ - triggering a one-on-one boss battle with a giant BT monster - it’s easy to defeat the creature or just run away. (Often it’s almost a viable tactic to get caught on purpose to clear the area as winning the boss fight gets rid of everyone.)

"There’s almost no real threat, and generally the worst that happens is damaging a package so much you fail the mission"

The lack of risk contributes to making it all feel a bit like a chore. There are always multiple deliveries on offer, leaving you juggling an eternal dilemma: do you pick it all up at once and be comically overloaded, your goods towering above as your knees buckle, risking falls that can dent your completion score, or fail you outright? Or do you take one thing at a time – a safer option that’ll have you backtracking endlessly back and forth one box at a time? It’s basically ‘Overencumbrance: The Game’. The essential gear you need – things like ladders and climbing ropes, healing Blood Bags and canister repair sprays to negate Timefall rain damage – all occupy the same boxed units as cargo that stack up on your back and body to the point that even a light loadout can quickly pile everything on. With more weight your stamina falls faster, you’re more likely to fall, and there’s more risk you can lose something along the way.

The game provides tools to help: things like exo-skeletons, floating trolleys and vehicles but it often feels like for every solution there’s a problem. When you eventually unlock the basic starter bike vehicle, and later trucks, it’s in a location so rocky and uneven it’s almost impossible to drive anywhere, as you clang and catch on rocks. Plus, batteries can run out and wheels can get stuck, so you take a risk loading up anything with more than you can carry alone should machines fail. Which, much of the time, pushes you back to being on foot, which is a frustratingly inconsistent experience. Stamina, footing, speed and ground angle all contribute to an animation system that can have you wrestling with the sticks and shoulder bracing buttons to stay upright should you trip. Your stability improves as you level up stats, and unlock better gear, but there’s always the lingering fear that the slightest movement could randomly result in anything from a skipped step to a full-sprint face-planting fall. It seems oddly scripted at times: I found catastrophic, can’t-stop-it tumbles far more likely to happen near ravine and cliff edges where I was, ironically, being so, so careful.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Network connections

There’s one other thing that also makes life easier, and that’s everyone else playing the game. There’s a wonderfully inventive asymmetrical online element that sees items and constructions from other players appear in your world and vice versa. The ladders and ropes you leave around on your travels appear for other people in their game. You can build bridges and roads, or contribute resources to other people’s, with the landscape slowly becoming more traversable as this equipment and structures appear, bearing the name of whoever originally built it and showing the ‘likes’ its received (one is automatically given whenever you use something, and you can add more with a button press or three).

It’s a fantastic idea; a lovely expression of strangers pulling together against an inhospitable world, adding moments of solidarity in an otherwise bleakly isolating world. The space where this system first comes into play is full of youthful enthusiasm, sprinkled with charging stations, roads, bridges and more as players test it all out. The further you get (both physically and in terms of time) progress slows and things are spaced out with a more weathered and functional minimalism. When the story moves to more mountainous routes, ziplines pop from peak to peak, becoming a literal game changer. Throughout, the idea holds up well as players collectively shape and inform the world through their actions, routes evolving over time. Someone’s bridge might become a crucial landmark, or let you negate some terrible, rough terrain. Your space becomes signposted and defined by the player tags attached to the things around you. You start to recognise these unseen faces as you repeatedly run into their traces. The names have meaning, so when you find items of lost cargo flagged with a friendly face you can return it for extra likes and the chance to pay it forward. It’s a game you play alone, but in a world you share.

The whole game riffs on this idea of connection. As mentioned already in the trailers (the only story stuff I’ll bring up) you play as Norman Reedus’ Sam Porter Bridges, tasked with saving the world through the medium of delivering stuff. You’re basically an apocalyptic Amazon Courier reconnecting a shattered America, location by location, to the Chiral Network, a sort of metaphysical AT&T that enables communication, as well as 3D printing of all your gear. You can’t see or access player structures until an area’s connected, or fabricate the gear you need to push on either, so making these deliveries is essential if you want to… make more deliveries.

A Hideo Kojima game

Obviously this is a Hideo Kojima game, which I’ve stayed away from until now in an attempt to discuss the game on its merits alone, without everything that name brings with it. It’s a name that obviously conjures up huge expectations and Death Stranding doesn’t entirely deliver on them. I can’t explain why in too much detail without spoilers but there are no real ‘holy shit’ moments, no surprises, just an okay-ish game about carrying boxes at the end of the world. The story is fine: high fantasy sci-fi full of Kojima’s trademark lengthy cutscenes, most of which involve characters explaining the story with broad swathes of exposition that doesn't so much break the ‘show don’t tell’ rule as pound it into submission with line after line of careful rationaled explanation.

There’s a lot of symbolism and metaphor spread thickly all over all of the story and characters, and some of it is incredibly literal – Mama is a mother, Heartman’s heart stops every 21 minutes, etc – some of it is nonsense. And plenty of it seems to exist just to provide the possibility for people to attach meaning to – like multiple slices of toast that may or may not contain the face of Jesus. At least a handful of critical plot points and elements seem to defy explanation or logic utterly, beyond a ‘ta-da!’ curtain reveal.

Death Stranding does have its moments though, despite the overall monotony of its principal activity. The groundbreaking visuals create a beautiful world, and there’s an incredible atmosphere when you reach a great view, or take a moment bathe in the glory of the snow crusted mountain you’ve just scaled. When the setting, progress and music combine it is a mood. If nothing else I’m a Low Roar fan now having played 70 odd hours of possibly the most expensive interactive music video ever made.

Progress is key to really enjoying it. I hit around 30 hours at the Chapter 3 mark, before I discovered I was barely a quarter of the way through and made the conscious decision to focus more on the story. Doing so gives everything more impact and meaning by bringing the cutscenes and story closer together, and adds more variety to what limited texture with a quicker progression of new locations, equipment and other things. You can spend days if not weeks making side-deliveries to a cameo heavy cast of survivors and gain little from it bar a deafening gulf between narrative beats that leaves fragmented isolated moments devoid of all connecting momentum. There is an okay experience here, filled with a scrapbooking hokum of afterlife mythology and pseudoscience, with a cast of likeable if bluntly literal characters but it’s a game that, ironically, is easily lost in its lengthy delivery.

I'm GamesRadar's Managing Editor for guides. I also write reviews, previews and features, largely about horror, action adventure, FPS and open world games. I previously worked on Kotaku, and the Official PlayStation Magazine and website.