Did the story in Days Gone suffer because it crashed up against the limitations of sandbox storytelling?

Bend Studio clearly struggled to decide what story it wanted to tell, but is the game's open-world structure partly to blame?

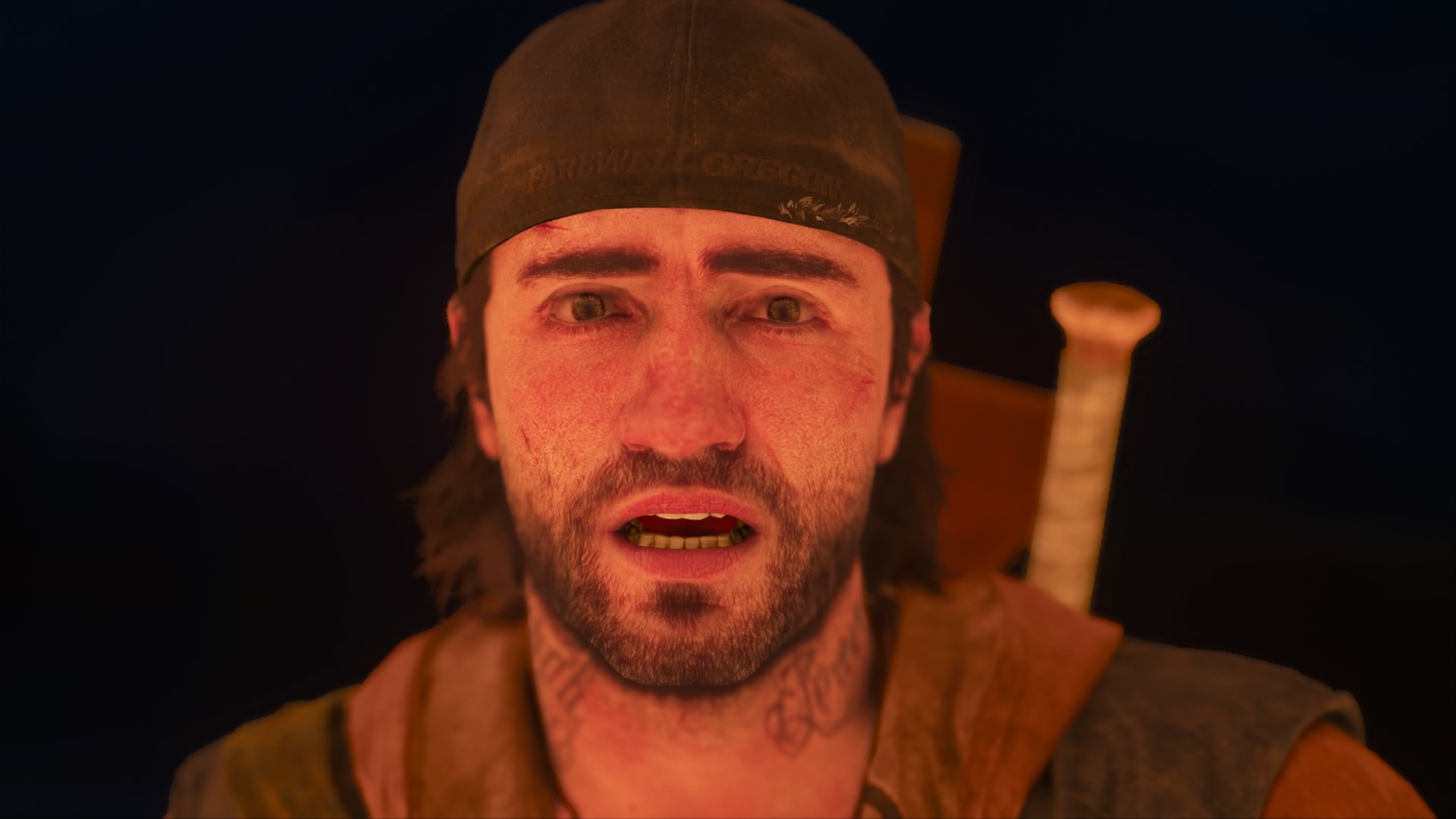

They say a man's got to do what a man's got to do, and it turns out Deacon St John has rather a lot on his personal to-do list. "A murdering drifter camp," he mutters during one excursion in Days Gone. "I've seen these bastards before, and I gotta take 'em out." Then, as we pass a group of ravens indicating a nearby Freaker nest: "I guess I'll come back and finish burning this infestation zone later." These are clumsy lines, and there’s a faint desperation about how frequently they crop up, especially when we can easily find these asides on the in-game map. If it wasn't already clear from the way tarted-up side-quests are folded into the main story, it seems Bend Studio really doesn’t want us to miss a single thing.

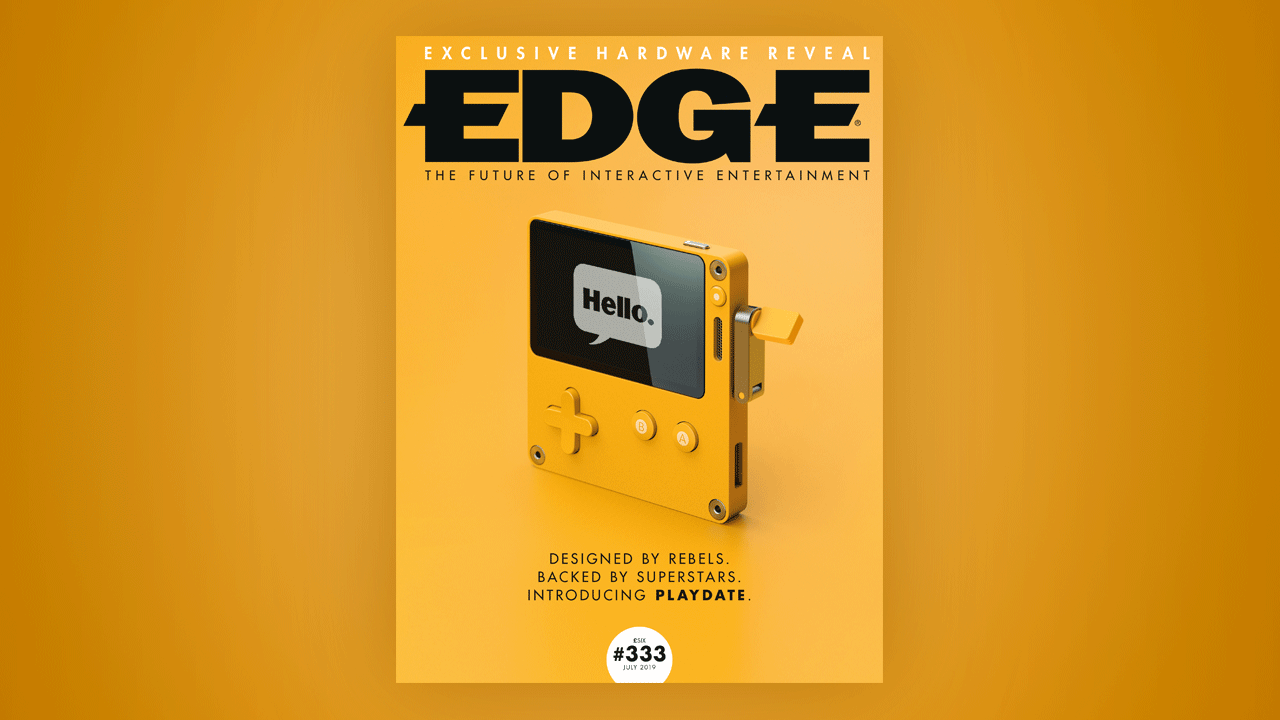

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine. If you want more like it every month, delivered straight to your doorstop or your inbox, why not subscribe to Edge here.

You'd think the life of a drifter would be ideally suited to the content buffet of your average open-world game. Yet Deacon St John is never really allowed to, well, drift. For someone apparently keen to remain untethered he's oddly willing to let himself become a dogsbody for the various quest givers at each camp, and his insistence that he absolutely must deal with every enemy encampment or Freaker nest he rides by leaves us convinced we've little choice in the matter, too.

You could, perhaps, argue that this is a deliberate contradiction: that his inherent decency, though often buried deep, prevents him from simply riding off into the sunset and leaving everything behind. And there is, in fairness, something in his past which explains his sense of duty. Vendors and other NPCs, meanwhile, seem utterly enamoured with him, frequently telling him what a good man he is, even when his actions (and words; he gives many of his supposed allies short shrift) suggest otherwise.

Lost in the wilderness

It's a discrepancy that speaks to a wider lack of consistency in Days Gone's storytelling, one that fatally compromises the credibility of the world far more than the occasional technical hitch. The duration of one of the shortest, easiest shootouts in the game is enough for one character to go from outright hating you to deciding you should run a camp together. You might also question St John’s moral code which forbids him from letting unarmed women to come to any harm, when he’s happy to shoot female marauders in the face mere moments later.

Consider, too, how you can return to the watchtower you call home in the early game for supplies, long after the person responsible for getting them has moved on. How motion-sensitive gates are probably not the wisest idea in a world overrun by cannibalistic creatures – especially since they're manually operated at all of the camps. How a quirk of voice direction means St John bellows his responses to radio broadcasts from an irksome 'truther'. Or how he later lies about his wife's name when it’s tattooed in giant letters on his neck.

None of this would matter so much if we had a compelling central plot to drive things forward. But this is a three-act game without much of a first act to speak of, weighed down by an interminable second. The opening cinematic sees St John putting his critically-wounded wife, Sarah, on a helicopter, staying behind to look after biker pal Boozer (who ironically seems more sober than his hot-tempered friend) while promising to meet up with her later. Fast-forward two years, and the two are surviving as drifters in this new Freaker-infested world, but with little idea of where they're going. It might be fitting for the drifter lifestyle, but nebulous talk of "heading north" to who-knows-where-and-what isn’t much to compel you to play further.

"At times it feels as if Bend Studio can't decide what story it wants to tell either, and so it borrows from other, stronger sources instead."

The 'is she or isn’t she alive' question crops up soon enough, but the constant desire to distract the player leaves Sarah's fate sidelined for hours at a time. All the while, we're left trying to get a measure of what kind of story this really is. Boozer's role in the early game seems significant, so is this a tale of male friendship in difficult circumstances? Or are we looking at a heartbroken man struggling to move on from his past? By the time we find ourselves juggling no fewer than 16 different storylines at once, it's become almost impossible to tell.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

At times it feels as if Bend Studio can't decide what story it wants to tell either, and so it borrows from other, stronger sources instead. The opening unwisely evokes The Last Of Us – needless to say, the comparison is hardly flattering – and it's not too long before we meet what appears to be this game's Ellie substitute, a young girl for whom our gruff hero gradually grows to care. Only it's not really a gradual thing. In lieu of more thoughtful character development, Days Gone bludgeons you into caring about her by repeatedly subjecting her to horrific trauma. Within the space of a single scene Deacon goes from reluctant saviour to bellowing "If you’ve hurt her, I swear to God" to no one in particular.

It's the kind of shock tactic the game leans on rather too often. Following the least surprising betrayal in living memory, we're asked to sit through a gruesomely sadistic torture scene. And, perhaps inevitably given the sheer volume of missions you have to undertake, there are some jarring tonal shifts – notably when a corny romantic flashback follows straight on from a grisly throat-slitting episode. And by the time it botches an emotional moment to which it's seemingly been building, it's perhaps time to concede that Days Gone's narrative shortcomings are more fundamental than a simple failure of structure.

For more features like the one you've just read, be sure to check out the Edge magazine channel page here on GamesRadar or visit MyFavouriteMagazines to check out the latest subscription offers.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.