Much as I'm loath to admit it, I've always been more of a breaker than a builder. Yes, I'm sure erecting a castle in Minecraft or tending your farm in Stardew Valley is all sweet and wholesome and nice, but it just doesn't have the same raw appeal of smashing the absolute shingle out of a building in games like Red Faction: Guerrilla. Give me a hammer and I won't see nails, I'll see panes of glass and structural weak-points.

So when I heard about Hardspace: Shipbreaker, a game in which you dismantle spacecraft for cold, hard credits, I was on its tail like a homing missile to a heat signature. Much to my surprise, however, Shipbreaker isn't the orgy of wanton destruction I'd imagined in my wrecking-ball of a skull. Instead, it's what I've come to describe as an anti-crafting game, and it's one of the most fascinating experiences I've had this year.

Deconstruction therapy

The best crafting games to whittle away your time with

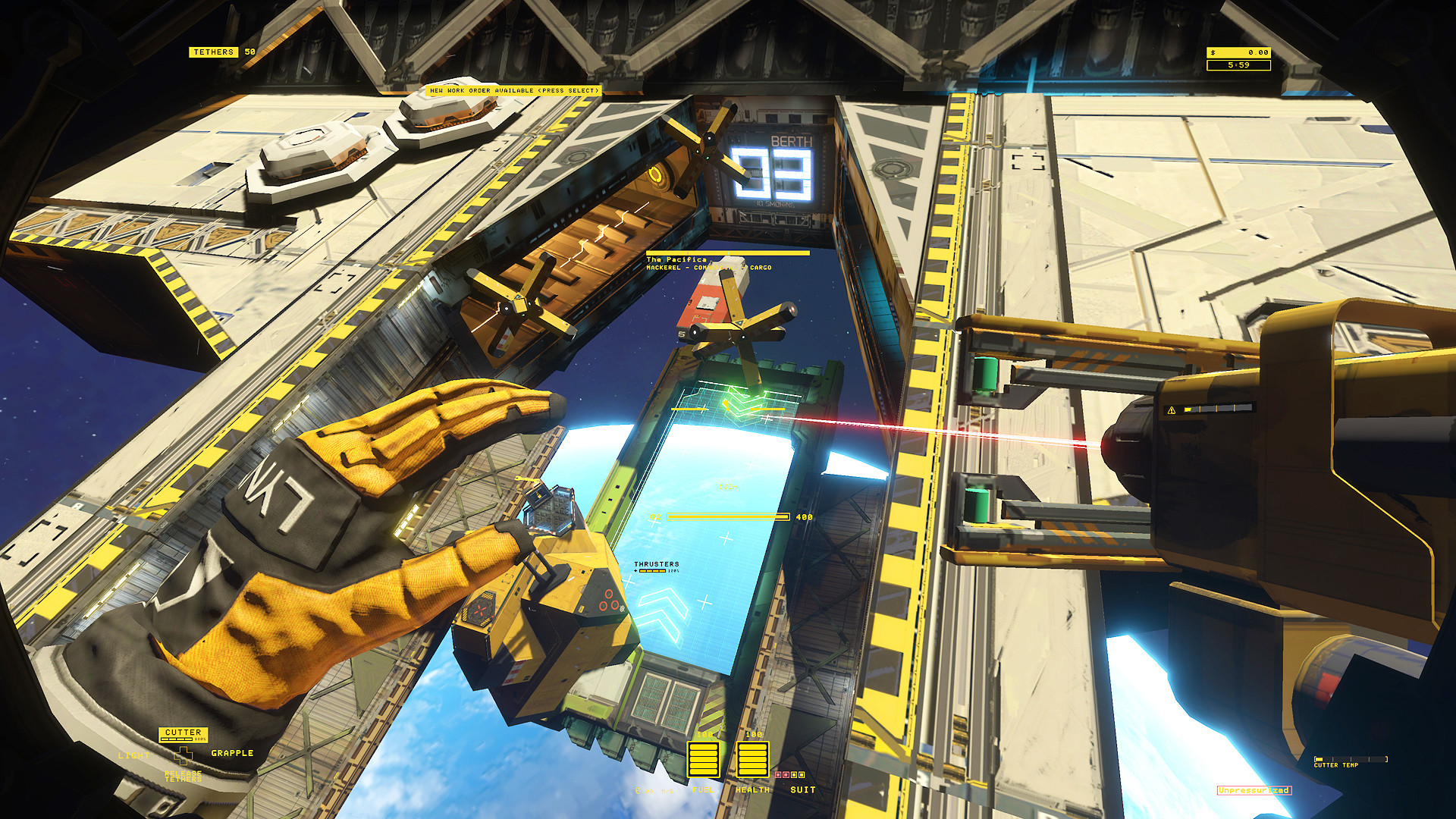

Shipbreaker puts you in the role of a newly employed worker bee of the Lynx Corporation, charged with recycling a celestial junkyard orbiting ring-like around an Earth proxy. Play sessions are split into "shifts", each of which involves transforming incomprehensibly advanced vehicles into carefully arranged piles of scrap. Starting each shift hovering above your exospheric shipbreaker's yard, you've got a couple of tools at your disposal, a worksheet of objectives, and around fifteen minutes to complete the job.

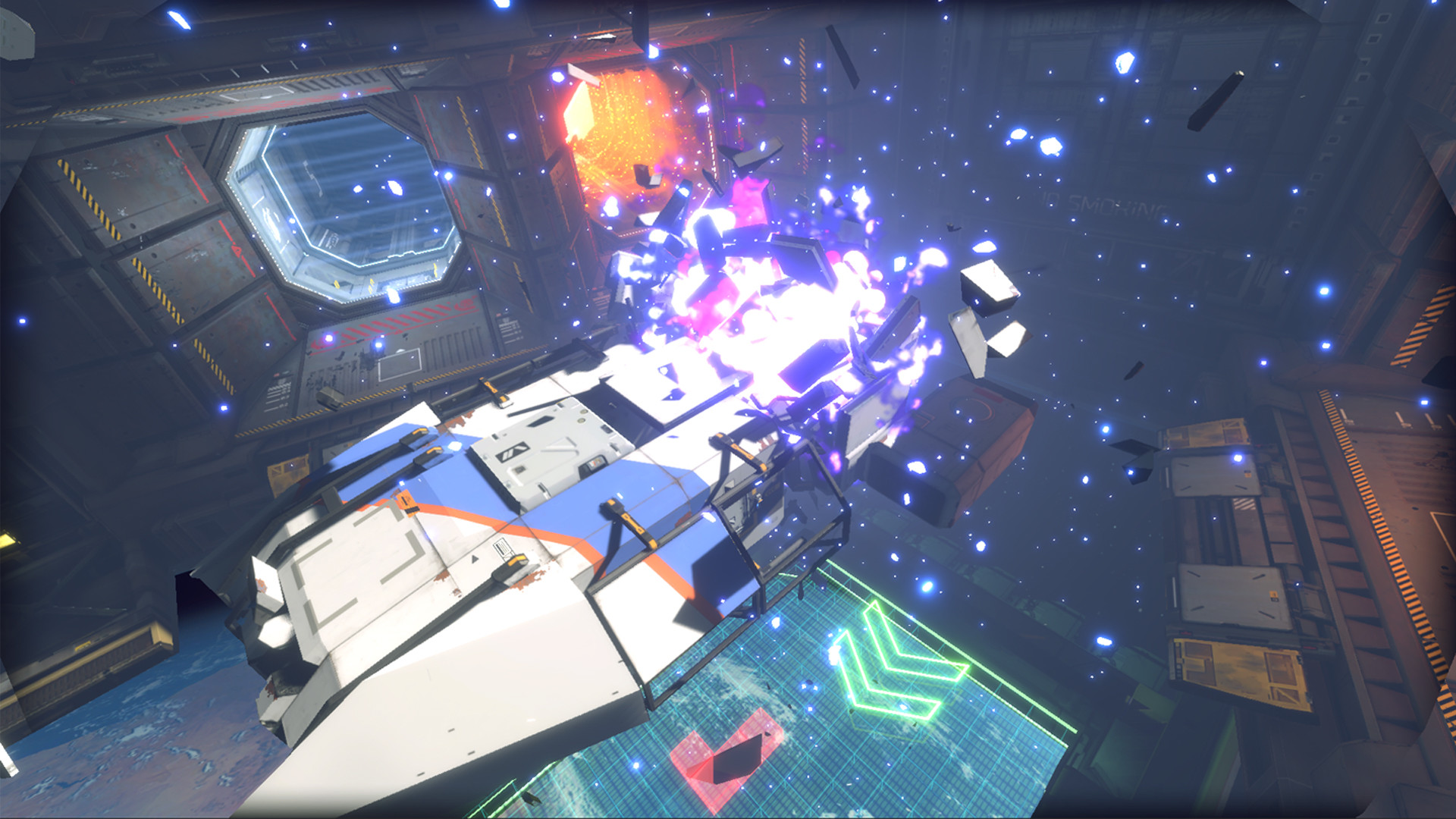

As I mentioned earlier, Shipbreaker isn't a smash-and-grab destruction game, it has much more in common with Surgeon Simulator, albeit with a more straight-laced tone. There are two ways to approach any given scenario, the right way and the deadly way, only the risks in Shipbreaker are all directed toward the player. The game's decommissioned vessels are hazardous environments. Crack open the hull without depressurizing the interior, and the resulting explosion will flatten you beneath several tons of high velocity nanocarbon. Accidentally catch a floating O2 tank with the beam of your plasma cutter, and you'll be the main course of a Zero-G barbeque.

With all this danger floating around, you need to approach each job with care, forming a plan of how to attack the ship and executing it precisely. I like to start by cutting off the ship's nacelles, before connecting them to inertial tethers (think giant elastic bands) that swoop down onto the salvage barge below. After that I'll head through the airlock, depressurise the interior, then perform the most dangerous task of any shipbreaking job; salvaging the reactor. Shipbreaker's reactors are basically timebombs, counting down to a massive explosion the moment they're yanked from their fastenings. My approach is to cut off the hull plate directly beneath the reactor, then tether it straight down onto the barge.

It's through this gradual development of personal processes where Shipbreaker's anti-crafting qualities emerge. The game has the same fundamental feedback loop of Minecraft or Satisfactory, but you're pulling something apart rather than putting it together. Like most crafting games, there's a survivalist bent to Shipbreaker.

Alongside the more exotic hazards of your job, you also need to monitor and replenish your jetpack fuel and your O2 supply. Running out of the former will force you to grapple slowly and perilously back to the refuelling platform. I don't think I need to explain what happens if you run out of the latter.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

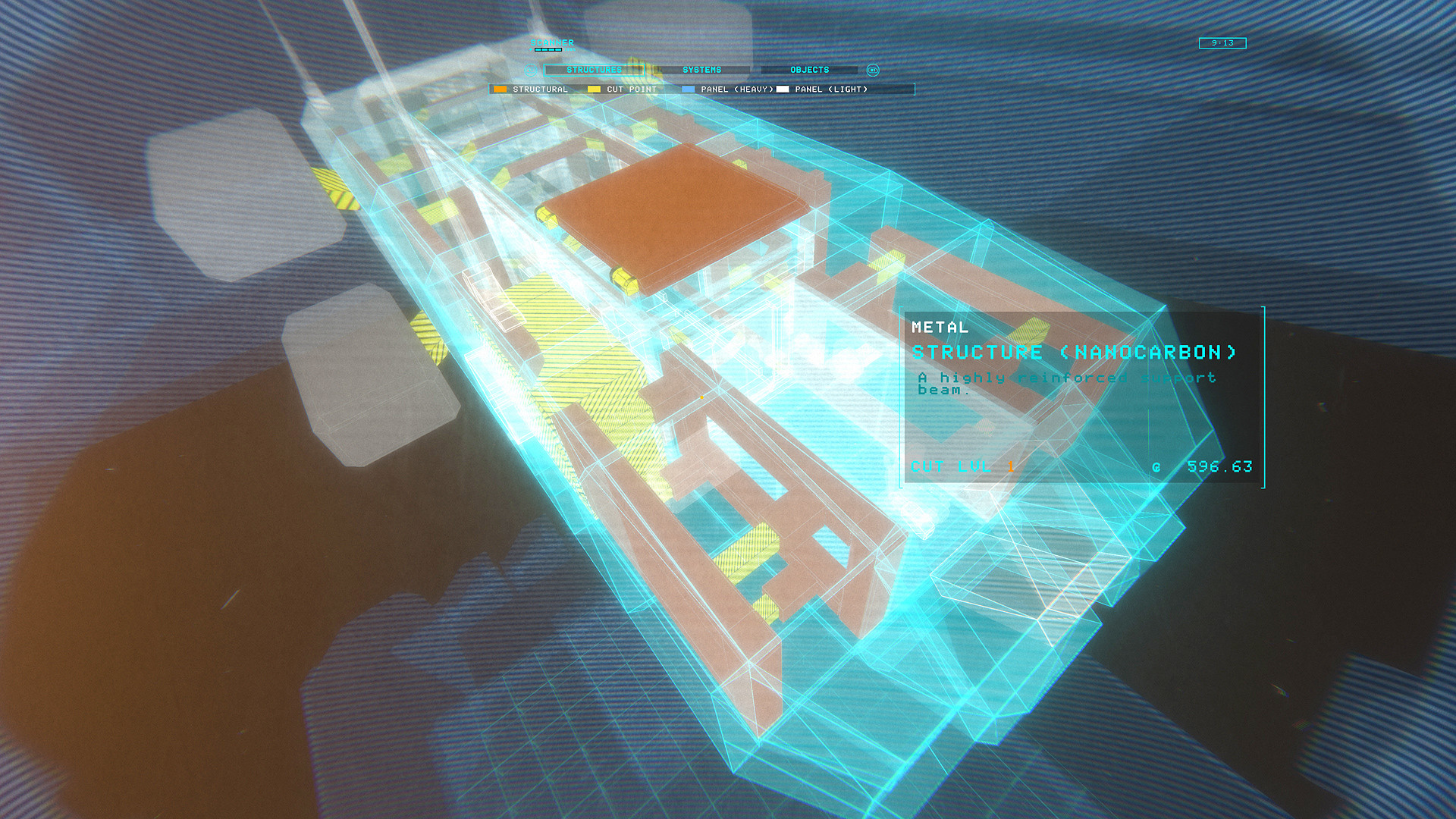

Resources are another important element of Shipbreaker. Individual parts of a ship are formed from different substances, and that influences how you need to salvage them. Complex components like reactors and thrusters need to be moved to the salvage barge, for instance, while compound materials like nanocarbon require transporting to the cryptically named "Processor", and metals like aluminium and titanium must be melted down in the furnace. Put these components in the wrong place, and it'll cost you credits. Believe me when I say this is something you want to avoid.

Satellite struggles

One of Shipbreaker's most interesting inversions of the crafting game formula is how it approaches player progression. Most crafting games are fundamentally about gain. Of resources, of money, or whatever it may be. In Shipbreaker, your ultimate goal is simply to get to zero. Lynx Corp's rigorous employee selection scheme has put you in the black hole to the tune of one billion credits, a debt that requires a Death Star's worth of salvage to shift.

As if this wasn't challenging enough, simply doing your job will constantly accrue further charges, from accommodation and tool repairs to the oxygen you need to breathe while floating in space. Even death is more costly than usual, as Lynx will clone your cremated and/or frozen remains posthumously, and charge you for the privilege.

As you may have guessed, there's an element of corporatist parody to Shipbreaker. Games that nudge and wink at you about how bad capitalism nearly always fall flat, with recent examples like The Outer Worlds and Journey to the Savage Planet offering plenty of absurdist style, but no real depth or sincerity. Shipbreaker, at least, is subtler in its "corporations are evil" theme.

Your trainer and supervisor, a man named Weaver, isn't some megalomaniacal middle-manager. He's pleasant, patient, and genuinely helpful in instructing you how to do this dangerous, unrewarding job. It hints at the insidiousness of how capitalist structures exploit people, rather than dancing around dangling the idea in your face.

"Hardspace hints at the insidiousness of how capitalist structures exploit people, rather than dancing around dangling the idea in your face."

The financial chasm you're thrown into isn't merely thematic. It serves a mechanical purpose too, adding a subtle but ever-present pressure to perform. This is layered atop another more immediate pressure, that of time. Each shift lasts only fifteen minutes, which is a heck of a deadline for carefully dismantling a whole damn spaceship. As a result, there's a nagging impetus to rush, to literally cut corners wherever you can. Some players have baulked at this added time-pressure, and as a result developer Blackbird Interactive has made it optional. In the context of worldbuilding, it is somewhat arbitrary, but I couldn't imagine playing without the buzz of adrenaline that the ticking clock provides, and the Damoclean disasters it nudges you to stand beneath.

Shipbreaker is currently in Early Access, but the core play is already well refined. Using your tools is simple and enjoyable, and the structural simulation of ships is both detailed and cleverly dynamic (ships will slowly collapse and pieces float away as you slice through key connecting points). That said, the current build is somewhat limited. There are only two ship-types available at the time of writing (although each has multiple configurations), and you only have access to a handful of tools.

Nonetheless, Shipbreaker's already a fantastic experience, offering both that gentle thrill of process that crafting games provide, but also the more immediate enjoyment of wrecking something. I do wonder, however, if it makes the most of its potential. Cracking open old and decommissioned ships for the first time is wonderfully exciting, but currently all you find inside is floating cargo and the odd audio-log. There's opportunity for Blackbird to conceal stranger surprises inside Shipbreaker's interstellar Kinder Eggs. Imagine cycling the airlock and stepping into an old derelict only to discover that something is living inside. That, I think would make Hardspace: Shipbreaker very special indeed.

Stay up to date with all of the latest releases with our upcoming games 2020 list, or watch the video below for our latest episode of Dialogue Options.

Rick is the Games Editor on Custom PC. He is also a freelance games journalist whose words have appeared on Eurogamer, PC Gamer, The Guardian, RPS, Kotaku, Trusted Reviews, PC Gamer, GamesRadar, Rock, Paper, Shotgun, and more.