Does Deathloop prove that 'immersive sim' is an outdated term?

Can Deathloop be called an immersive sim?

Agreeing with a door isn't something we often find ourselves doing – not even in games. But the very first time you encounter one in Deathloop, it's locked with a four-digit keycode. "You know the code," the game tells you, over and over, in hovering captions that flicker in the air. And so, a certain type of player will obediently tap in the numbers, as they have many times before: 0-4-5-1.

Nope. Sorry. Try again. It's a brilliant little tease, the game winking as it slips you an achievement for being such a good sport: 'Old Habits Die Hard'. But it's more than that – an acknowledgement that Deathloop is breaking free of the tradition represented by those digits, a tradition in which Arkane has been steeped since its founding: that of the immersive sim.

It's an imperfect label, not least because that leaden pairing of words somehow manages to be less evocative than the bare numbers. But also because the bounds of what they describe have always been a little blurry. Is Breath Of The Wild an immersive sim? What about Firewatch? Or Jalopy?

Breaking away from tradition

This feature first appeared in Edge magazine. For more like it, subscribe to Edge and get the magazine delivered straight to your door or pick it up for a digital device.

Arkane's games have always cleaved close to what we might call the Austin Interpretation, the canon of Garriott and Spector and the others who passed through the doors of Origin, Looking Glass and their descendants. To be incredibly reductive for the sake of argument, Dishonored is an extrapolation of Thief; Prey, a reimagining of System Shock. But of late, the studio increasingly seems to be treating the immersive sim as a problem to be solved.

Prey's Mooncrash expansion was the first to break from the orthodoxy, borrowing its structure from Roguelikes. The next game from that team (in Austin, naturally) is Redfall – so far, all we have to go on is the E3 trailer, but that made it look like a closer relative of Left 4 Dead than Deus Ex. Speaking to the Lyon team responsible for Deathloop in Edge's 357's cover feature, we tried to establish how far the game departed from the immersive-sim formula. Now we have our answer.

In play, it's clear that Deathloop's influences reach far beyond the traditional scope of the immersive sim. It's not (at the risk of evoking another slightly hazy set of genre rules) a Roguelike, but its structure certainly borrows from them. There are parallels here to the joy of gradually earning Zagreus's weapons between runs through Hades; the sense of frustration with yourself in Spelunky when, even though a hundred similar mistakes have taught you better, greed tempts you away from the safety of a level's exit.

This same magpie approach is taken across the breadth of the finest games from the past decade or more. Waking up on the beach at the beginning of a loop is not too far from waking up next to Outer Wilds' campfire. Building up a stock of Residuum before deciding to try something risky is sweaty in the same way as accidentally wandering into an uncharted area of Lordran or Yharnam, your character loaded with souls. There's a lot learned from the structure of IO's latest Hitman trilogy, which is arguably an immersive sim in its own right, and from the potent synergies of building a deck in Slay The Spire, which is not.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

And, as we noted with surprise in that cover feature, there's a renewed focus on full-blooded action rarely seen in these games, at least outside of the BioShock series. (Is BioShock an immersive sim? Please show your workings.) Like those games, Deathloop cuts loose many of the trappings associated with the traditional immersive sim: the non-lethal solutions, the ability to drag bodies, the tendency to load up a save the moment something goes wrong.

That last one speaks to Deathloop's biggest departure: its structure, which seems to have been designed to address some of the flaws of the immersive sim. These are games in which you can try anything, and it should work, but that tend to encourage a certain straight-down-the-line perfectionism in their players. When stealth slips into unsolicited action here, you've no choice but to accept it, and enjoy Deathloop as a brilliantly messy shooter.

More than that, the loop unpicks another defining feature of the immersive sim, one that's rarely included in the bullet-pointed list: the sense that the game is bigger than what you're seeing. The other paths you could have carved through a level or along the branches of the skill tree. The possibilities you only learn about when you speak to other players or begin a new save. In Deathloop, you can see it all within a single playthrough.

The game's greatest pleasure comes from knowing the mission ahead of you, examining the tools at your disposal, and combining them into a plan. And because you pick a tight loadout before each mission, you get to do it over and over again – meaning you get to play as the stealthy infiltrator and the human tank rolling over the skulls of your enemies, and many roles in between. We find ourselves jotting down possible combinations in a notebook: poison-gas- chugging trapper, temporarily invulnerable demolitions expert, a machine-gunner invisible as long as they stay in one spot.

Which, as we lay it out, is the exact same pleasure that IO has so brilliantly tapped into with its recent games. We might just be living through the birth of a new genre, or at very least an offshoot of the immersive-sim principles deserving of its own label. Maybe we can even come up with a better name for it this time.

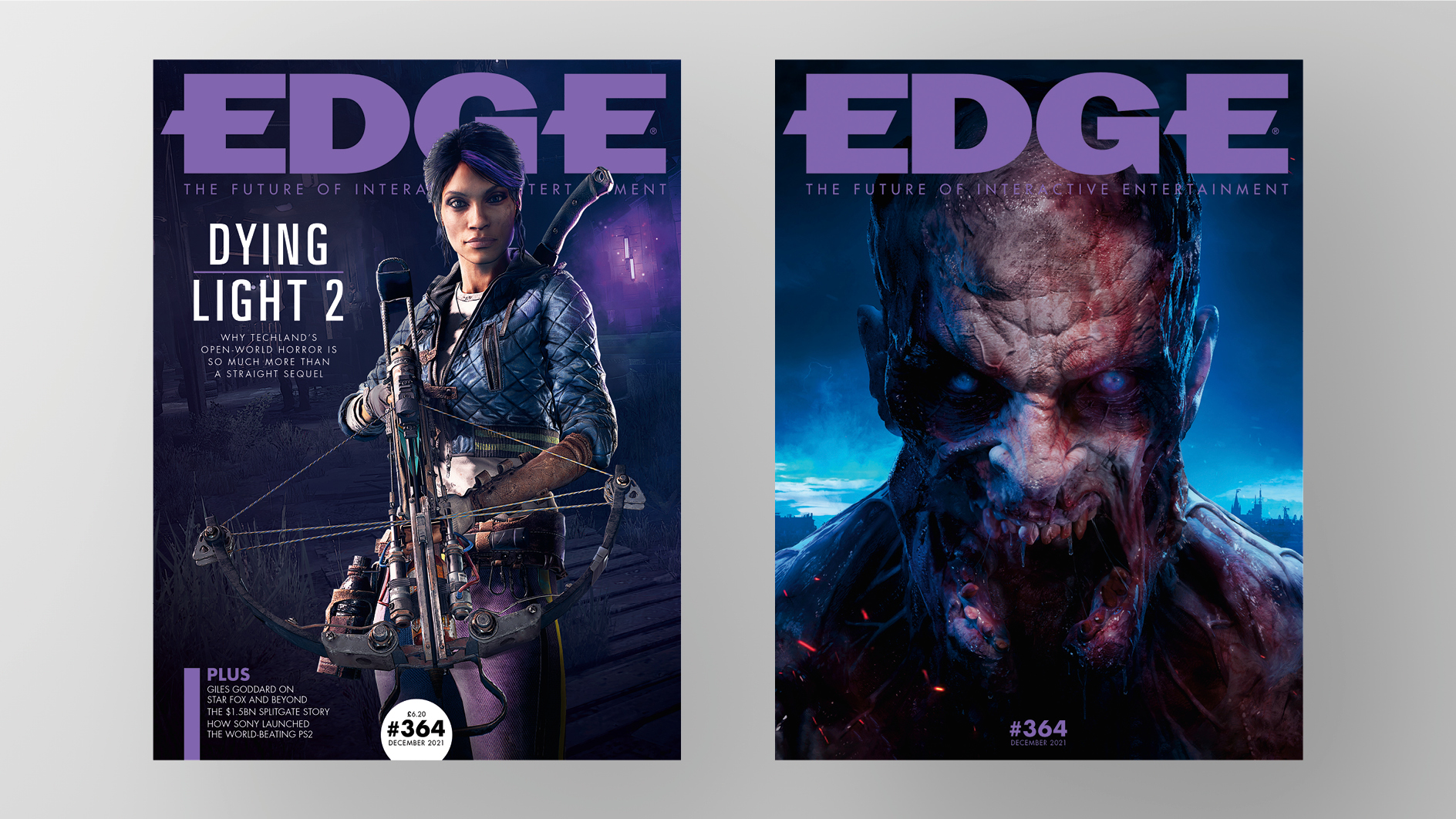

For more fantastic previews, reviews, and in-depth features, you can pick up the latest issue of Edge magazine from Magazinesdirect today.

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.