Donnie Darko at 20: How director Richard Kelly made the cult classic

Director Richard Kelly walks us through the making of his head-spinning cult classic Donnie Darko on the movie's 20th anniversary

Boy meets girl – it's an everyday story. Except when boy meets girl in a Tangent Universe created by a rupture in the space-time continuum, due to boy sleepwalking as a jet engine falls on his bedroom, setting girl on the path to being run over by a car driven by a guy dressed as a demonic rabbit. Then boy must set the universe back on track, sacrificing himself to save girl – and the world.

Twenty years have passed since Richard Kelly’s mix of mind-bending sci-fi and high school slice of life debuted at Sundance, and the film continues to fascinate (and confound) audiences. It’s an achievement even more remarkable when you consider that the first-time director was a callow 25-year-old when the cameras rolled.

“I was very young,” Kelly tells SFX, seemingly scarcely able to believe it himself, “And god, the world was so different. I was just out of college, I’d gotten this incredible opportunity, and it was a life-changing experience. But it’s an ongoing experience!”

David Fincher is responsible, to a degree: his video for Aerosmith’s “Janie’s Got A Gun” inspired the 14-year-old Kelly to become a filmmaker (he called up MTV to ask who made it!). But the specific spark was a newspaper article about an occurrence in Kelly’s home state, Virginia.

“A large piece of ice fell off the wing of a jet plane and smashed into a house somewhere near where I grew up, into the bedroom of a teenage kid,” he recalls. “He wasn’t in his bedroom, but it damaged it. I remember reading about the story, and it always stuck with me how disturbing that might have been for that boy. It must have felt like, ‘Is that some kind of warning?’ What was the psychological impact of that event on that teenage boy?”

For Kelly, not long out of USC film school in 1998 and “in a panic” about how to build a career in the industry, this seemed a promising conceit. So he began interrogating the concept.

“I thought, ‘Okay, piece of ice – that’s interesting. But what if it’s an engine that falls off a plane?’ Then I thought, ‘What if they never found the plane, and that’s part of the mystery: figuring out where the engine came from?’ And then, ‘If he got out of bed, why? What is this voice that draws the teenage boy out of bed to dodge this bullet from the heavens? What’s the journey he goes along?’

Sign up to the SFX Newsletter

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

“My mind actually works in a pretty logical way, believe it or not!” he laughs. “All the crazy films I make come from a scientific operating system. So then I built the architecture of this story. I decided it should take place over a synodic lunar month – somewhere between 27 and 29 days. And I started building all this science into the journey. I thought, ‘Well, he dodged the jet engine, so he must be a superhero’, so I gave Donnie a superhero name. And then I thought, ‘Well, no one’s really doing ’80s period pieces...”

Heart of Midlothian

The screenplay emerged stream of consciousness-style – almost as if Kelly was (to use his terminology) one of the “Manipulated Living” – within roughly the same timeframe as the film’s countdown to the end of the world. “I wrote it in about 28 days, and it just poured out of me. The first draft was pretty long – 150 pages or something – but it was pretty damn close to what you see. In terms

of the architecture of the story, everything you see in the finished film was there.”

Though critics often draw parallels with the work of Steven Spielberg, Robert Zemeckis, and John Hughes – all of whom the young Kelly admired – he stresses that he didn’t consciously set out to imitate them. “Their films are all imprinted in my subconscious mind, but the idea of ‘I’m writing a high school film’ wasn’t my thought process.”

Instead, he tapped into personal experience. “I drew a lot from my hometown in Virginia [Midlothian], and the teachers I had growing up, and all my friends and their parents. The environment of suburban Virginia was very much an influence upon the landscape which I was crafting.”

When the script began doing the rounds, it generated considerable buzz, but it was only thanks to the enthusiasm of two actors that it finally got greenlit, after a year of pitching. Firstly there was Jason Schwartzman, fresh from his success in another offbeat high school movie, Rushmore. “Originally, Donnie was going to be played by Jason,” Kelly explains. “I owe him an enormous debt. I don’t think I’d have a career if it weren’t for Jason and his support. I think Jake would say the same. He helped bring a lot of enthusiasm and financing to the screenplay.”

A scheduling conflict eventually caused Schwartzman to drop out, but his agent had brought it to the attention of Nancy Juvonen, producing partner of Drew Barrymore. She then became the project’s “godmother” (and also liberal English teacher Ms. Pomeroy).

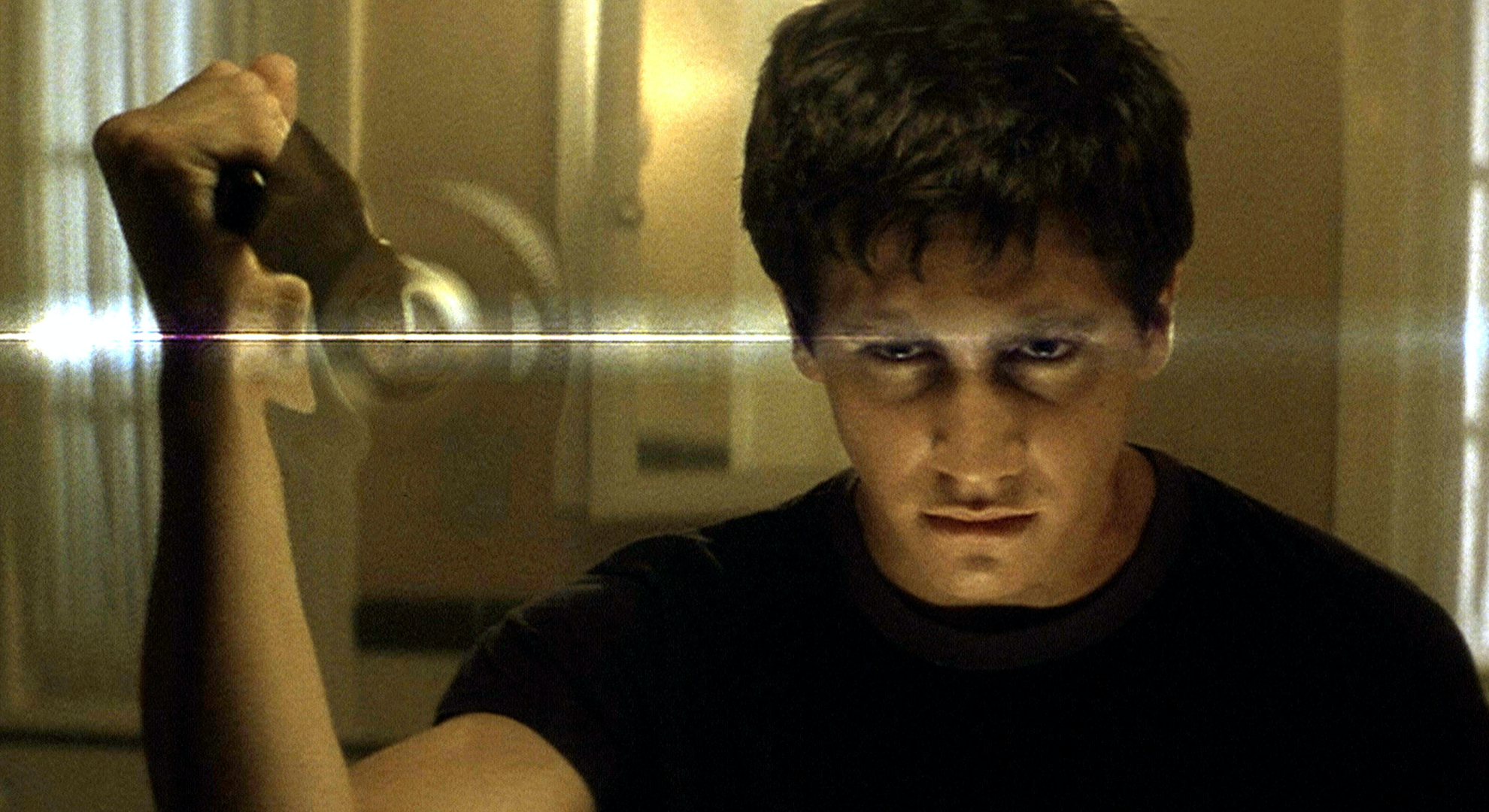

It was in Barrymore’s office that Kelly first met his Donnie, Jake Gyllenhaal (pronounced Jee-len-hall-er, for those still unsure...). “Within 30 seconds, it was clear to me that he was the right actor,” Kelly says. “It was a gut intuition that he was the one. He kind of came from showbusiness royalty [director father, screenwriter mother] and I felt he was an incredibly strong anchor for the film.

“And he delivered: he really put all his blood, sweat and tears into that role. It was a make or break situation for both of us.”

Another key collaborator was cinematographer Steven Poster, whose CV caught Kelly’s eye thanks to second unit work on films like Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, and collaborations with Ridley Scott. Despite a nearly 30-year age gap, the two proved to be sympatico, with Poster the perfect foil for his strong-willed fledgling director. “Steven was a wonderful collaborator,” Kelly says. “He’s very collaborative, and works well with someone who has a strong point of view, and he’s very good at supporting that point of view, with a lot of strategy.

“He’s not combative; he helps course-correct and guide you in the right direction. When, y’know, I wanted to do a Steadicam shot that would take way too much screen time, he’d advise me how to divide it up into three sections. He brought decades of experience that I didn’t have.”

It helped that Kelly – who got into USC on an art scholarship – had a clear vision of how the film should look. “I had all these drawings and illustrations, so I could show Steven those. And I’d already done some sketches for the film itself.” You see several of these on-screen: a sketch of Frank the rabbit that the troubled Donnie, haunted by visions of the bunny, tacks to his calendar; the “infant memory generator” concept he discusses in class; the design for the sinister Frank mask.

The two also “referenced a lot of films” in their discussions. The opening scene, for example, in which Donnie wakes up on a hillside, took inspiration from Montgomery Clift’s introduction in 1951’s A Place In The Sun. Kelly also watched Stanley Kubrick’s Lolita (1962) several times as preparation (something nodded to in the Halloween party scenes: Donnie’s sister’s costume resembles Lolita character Vivian Darkbloom).

“One in particular might be surprising to people,” Kelly says. “We were going to photograph the movie in Southern California, and it kind of exists in a fantasy suburban landscape, and a film I referenced for Steven was Peggy Sue Got Married.”

Francis Ford Coppola’s movie sees Kathleen Turner’s character leaping back into the body of her teenage self, during her high school senior year. “It was shot by Jordan Cronenweth, who shot Blade Runner, and Steven Poster shot second unit on Blade Runner,” Kelly explains. “So I drew this connection between Jordan Cronenweth, Steven Poster and Francis Ford Coppola. Plus I’d had a meeting with Coppola – he was very interested in financing Donnie Darko.”

In Kelly’s view, drawing inspiration from Peggy Sue made good sense, given that (although largely set in 1960) it was released in 1986, close to the timeframe of his movie.

There was something about the photography and the suburban polish that I found very elegant about that film. So that was our reference point that we started with, and it sort of evolved... I remember that with the outfits for [high school dance troupe] Sparkle Motion, we modeled the silver fabric of their outfits after Kathleen Turner’s prom dress in Peggy Sue Got Married.”

When asked to identify principal photography’s biggest challenge, you might think Kelly would plump for, say, dropping an old jet engine through a bedroom set. But what springs to mind is the early days on location at LA’s Loyola High School, when he was still proving himself to the crew.

“The hardest part was the first week,” he says. “It’s usually like that for me, because I’m always trying to do so much with not enough money, and not enough days, not enough hours in the day! So that first week is really terrifying for everyone. And it was extra terrifying because it was this wild, provocative script that no one could really categorize, and we needed $10 million but only had $4.5 million, and it was this crazy 27/28 days schedule – the same schedule as the Tangent Universe in the movie. And here I was, I’d just turned 25, and a lot of people were doing side-eye at each other, like, ‘Does this guy know what he’s doing?’”

A turning point was nailing the montage which introduces the staff and students of Donnie’s high school, to the strains of Tears For Fears’ “Head Over Heels”. “We did the big Steadicam sequence through the hallway, which is about four or five Steadicam shots,” Kelly remembers. “That was half a day, shooting all that stuff, probably on day three of production. Everyone was really really not happy that I was shooting that, because it was essentially a music video, for a song that we didn’t have the rights to yet!

“We hadn’t even contacted Tears For Fears, and the whole thing was meticulously choreographed to ‘Head Over Heels’. And I was insistent that we do this sequence. I was just adamant.”

Kelly hid in a classroom, calling out instructions for changing the camera speed. Afterwards, he had the footage hurriedly digitized, and a rough cut rushed to set. “It was a VHS tape – because we were still looking at things on VHS in the year 2000! I brought all the crew into my tiny trailer, put the tape in the VCR, and showed them the sequence cut together to the song. Everyone immediately

flipped out. They got it. They were so excited. You could see everyone breathe a sigh of relief that I just might know what I’m doing!”

On general release in October 2001 (about six weeks after 9/11), Donnie Darko did not set the world alight. It screened in just 54 cinemas, to little fanfare. But a year later, the UK release met with a rapturous reception. This gave the film a second wind in its homeland, with Kelly given the chance to reinstate scenes he’d reluctantly trimmed to squeeze the duration down, for a Director’s Cut revival.

Two decades on, it’s a film with a devoted cult following, and still inspires fervent theorizing. “I try not to focus on the fan theories, because I have my own,” Kelly says. “There’s so much going on in this movie, and so many Easter eggs hidden in it. A lot are kind of staring you in the face, but you don’t realize what you’re looking at; things that people probably still haven’t figured out, that maybe I’ve figured out. I’ve lived with it now for 20 years, and I’m trying to constantly look at it with fresh eyes, but also as an analyst – kinda like my dad, who was a scientist.” Lane Kelly worked for NASA, and helped design cameras for the Viking Mars probes.

“I try to look at my own film not only as an architect, but as a scientist,” Kelly continues, “And focus on an interpretation of the science fiction logic of the film, and keep building upon it and developing it. Because there really is so much there. In a lot of these stories I tell, the blueprints are rich with a lot of detail, and there’s a lot of stuff underneath the surface that you can’t quite comprehend, or maybe needs further exploration.”

A sequel already exists – 2009’s S. Darko, centered on Donnie’s younger sister. But Kelly had zero involvement with that. “I’ve been working on a lot more story that could exist in the Donnie Darko universe, and it’s been really rewarding,” he reveals. “I’ve been under a lot of pressure to deliver – a lot of people are very passionate about me returning to this world.”

“There’s a scene in the film where you see Donnie lying in bed, and he’s playing with a Rubik’s Cube, and he looks over at a calendar, and the days are ticking by,” Kelly notes. “I’ve kind of been with my own Rubik’s Cube, trying to solve the puzzle. I’m very excited about what the future could hold, and that there could be a much bigger, much more exciting story which could be told in this world. So we’ll see.”

This feature first appeared in SFX Magazine. For more great features, make sure you subscribe and get them sent straight to you mailbox – both physical and digital.

Ian Berriman has been working for SFX – the world's leading sci-fi, fantasy and horror magazine – since March 2002. He's also a regular writer for Electronic Sound. Other publications he's contributed to include Total Film, When Saturday Comes, Retro Pop, Horrorville, and What DVD. A life-long Doctor Who fan, he's also a supporter of Hull City, and live-tweets along to BBC Four's Top Of The Pops repeats from his @TOTPFacts account.