E3 is open to the public for the first time in 2017... but is it really about gamers any more?

Inviting 15,000 fans to the world's biggest games show is a welcome move, but driven as much by finance and the power of social media as romance

For the first time in the show’s 23-year history, E3 2017 is open to the public. A total of 15,000 consumer passes, priced between $150-$250, will grant show-floor access to holders at the Los Angeles Convention Center this year, where they’ll join the ranks of the journalists and buyers who’ve traditionally attended in the past. Press conferences remain off limits to these pass holders, but with a number of separate events like Microsoft’s Xbox Fanfest 2017 and Sony’s E3 2017 PlayStation Experience also open to the public, it’s clear that this year E3 is certainly not just the domain of the games press and retailers.

That’s a big deal. On the surface it seems to indicate a sea change for the games industry’s biggest trade show, transforming it into a place for game companies to communicate with their audiences directly rather than using journalists or influencers as their middle-men.

With the show’s relevance open to debate after recent absences from big players such as EA and Activision, this also seems a fairly transparent move in direct response. After announcing consumer pass availability, ESA’s VP of communications Rich Taylor told Gamespot, "It's a changing industry, and E3 has always evolved to meet industry needs and anticipate where we’re heading together - as an event, as an industry, and as fans. The decision to open our doors to 15,000 fans was a strategic decision.”

Major publishers offered positive responses to the announcement. Speaking to gamesindustry.biz, a Ubisoft representative said it “supports the ESA's approach to open up E3 to more consumers” and that “getting games in players' hands early and hearing their feedback helps our industry, both in terms of improving the quality of games and shining a light on new and innovative ideas and technology."

The official messaging is clear and simple. That’s not to say it shouldn’t have a liberal dose of scrutiny applied to it, if not outright cynicism.

All about the money

Let’s put the move into some context. No-shows from the likes of EA and Activision aren’t E3’s only image problem - in recent years, as talk has settled around which companies ‘won’ or lost’ the show on social media, we’ve seen share prices take dramatic changes in direction in the conference’s immediate aftermath. Square Enix’s value gained 3% practically overnight following its announcement of the Final Fantasy 7 remake in 2015, while Nintendo stock suffered the opposite extreme following the Wii U’s unveiling at E3 2011, dropping 5% in a 24-hour period. A lot of the coverage you’ll see surrounding E3 2017 this year will be about share values, too. It’s become as ubiquitous to the show as Aisha Tyler (who - ironically - isn’t at the Ubisoft conference this year) dropping an f-bomb during a Twitch stream, or a platinum-selling mega-band of yesteryear plumbing new depths by taking to the stage of a publisher’s post-conference party.

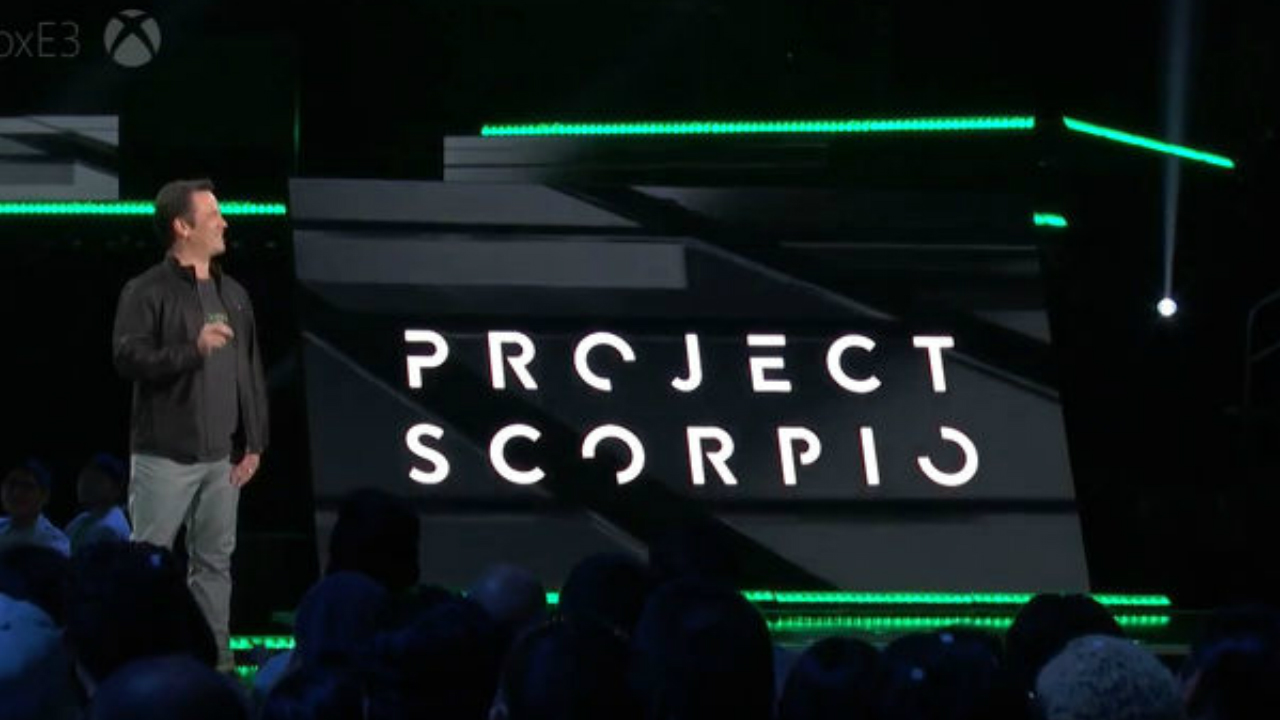

All of which is to say: E3 isn’t just a place to announce new games. It’s a major strategic stronghold for platform holders, as you’ll see this year when Microsoft attempts to gain ground on Sony with Project Scorpio. It’s a week that might decide the fortunes of a company for years to come, and gamers from the press and public alike are all becoming increasingly aware of its business smoke and mirrors.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"We’ve learned in no uncertain terms that E3 is as much about appearances as it is about final products."

We know that those ‘gameplay trailers’ don’t contain any gameplay, and that even extended onstage demos might be a wildly inaccurate representation of the final game. The word ‘downgrade’ is part of everyday gaming lexicon, and no one has forgotten about No Man’s Sky or even Killzone 2 quite yet. In short, we’ve learned to be cynical. We’ve learned in no uncertain terms that E3 is as much about appearances as it is about final products.

Arguably, that image problem E3 has been developing comes from the plain and simple fact that it was never intended as a public-facing trade show at any point from its inception in 1995, and yet the public have become increasingly interested in it with each passing year.

When the Interactive Digital Software Association (IDSA, now known as the ESA) created the first Electronic Entertainment Expo in ‘95, they did so as a direct response to years of second class treatment at the hands of the Consumer Electronics Show (CES). CES wasn’t just about video games, it was a place for refrigerator manufacturers, TV bigwigs, pornographers, and telephone operators to show off their latest innovations. During the summer shows in Chicago, the entire bottom floor of the conference hall was reserved for pornography exhibitors. Games companies had the floor above it. It was a conference bustling with electronics industry professionals who had no knowledge of or interest in video games.

For the players

So when the games industry broke out and held its own conference, it did so - as one spokesman at the time put it - so that “I never had to explain that games consoles did not have defrost buttons.” E3 was somewhere the likes of Sega and Nintendo could communicate with journalists and retail executives directly, away from the refrigerator crowd. Still deep into the days of print media, the only way conferences were relayed back to members of the public was via magazine coverage. It was at this point that the marketing practices of E3 were forged, to be called upon for decades after, and they were forged for industry professional consumption.

Times have changed. Conferences are streamed via Twitch and attract audiences approaching one million concurrent viewers. Trailers that debut at E3 are uploaded to publishers’ YouTube channels seconds later and accrue millions of views. Memes emerge and permeate into the wider consciousness of people who’d never dream of staying up late to watch executives perspire in front of a brutal melee takedown on the big screen. By 2016, and indeed for the preceding decade, E3 had become a very, very public conference.

One area in which it had remained the same, though, had been its attendance policy. While conferences at the Los Angeles Convention Center broadcast to millions of people across the world last year, the only attendees within the center were industry professionals. Those attending in a press capacity were doing a very different job than their colleagues of a decade prior: rather than reporting dispatches from an exclusive event, they were there to articulate the public consensus and present it back to them. Everyone knew Sony had ‘won’ E3 in 2013, but the task remained to organise the blows of Microsoft and Sony’s battle into cogent order. The outpouring of emotion for Shenmue 3 was obvious in 2015 before the army of attending journalists began to hit their keyboards, and yet the keyboards rang out just the same. It’s perhaps also in that strange and complicated relationship between exhibitor, press, and public that the growing cynicism towards E3 and AAA marketing practises in a wider context have arisen.

But this year, ostensibly, is different. 15,000 members of the public are permitted to buy their way into that previously exclusive domain, and companies are welcoming the opportunity to receive direct feedback from players on the show floor. Public attendees don’t have industry relationships to manage, nor financial interests to nurture. They’re grassroots campaigners for the games they discover at the show and connect with.

At least, that’s the idea. The impact of those 15,000 voices on social media has yet to be seen, but in reality the game companies who welcome the opportunity to communicate with and gather feedback from their fans directly have been doing exactly that for years. They’ve been doing it with the aforementioned Twitch streams and YouTube uploads, and in instances like Battlefield Hardline’s surprise beta during E3 2014. That’s the only useful way to gather feedback during a conference, after all. Hand on heart, every developer out there this year knows they’re not going to be taking notes during hands-on sessions on the show floor and changing the trajectory of their game’s development in response.

So, who is E3 really for, and why is it open to the public this year? The most likely answer is that it will always have to maintain an industry focus by its very design, but at the same time its organisers must continue to adapt its format in response to the millions of gamers who show an interest each year. Those 15,000 consumer passes are a PR exercise like everything else at the show, but they’re also an admission that times change. The ‘winner of E3’ is decided on social media, in YouTube comments, and on Twitch just as much as it is within the confines of the convention center, but through public admission, the battle for the hearts and minds of actual players just got a little hotter in 2017.

Phil Iwaniuk is a multi-faceted journalist, video producer, presenter, and reviewer. Specialising in PC hardware and gaming, he's written for publications including PCGamesN, PC Gamer, GamesRadar, The Guardian, Tom's Hardware, TechRadar, Eurogamer, Trusted Reviews, VG247, Yallo, IGN, and Rolling Stone, among others.