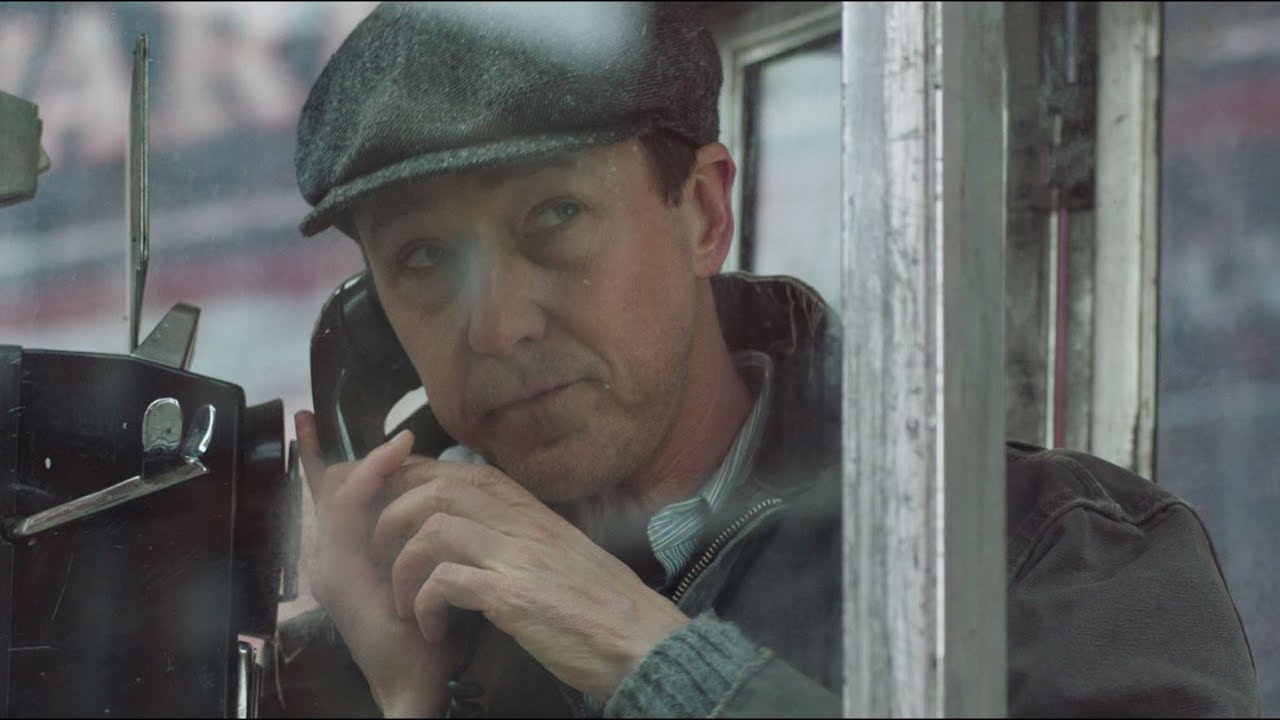

Edward Norton talks Motherless Brooklyn and Martin Scorsese's "astute observations" on the film industry

The Fight Club and Hulk actor discusses his new movie with GamesRadar+ and Total Film

Edward Norton still gets nervous. Despite having a career that goes back decades, starting in 1996 with Gregory Hoblit's Primal Fear, the actor still worries about acting the fool in front of other people. "I wish I could say I was a person where I didn’t care who was watching," he tells GamesRadar+ and Total Film while promoting Motherless Brooklyn, a movie he has written, directed and stars in.

Luckily, though, Norton has friends in high places, namely Bruce Springsteen, who are there to reassure him. Yes, we're talking about The Boss. "Bruce Springsteen saw the movie recently," the Fight Club actor says. "He was really, really nice about it. We were talking about a lot of stuff, and I said something to him: 'Were you always fine to be in the studio, working on songs, no matter who was there?' And he was like, 'Oh my God, no. There were some times I didn’t even want the guys in the band around.' If Bruce Springsteen doesn’t want anybody around until he thinks he’s got it right, then I guess we’re all still a little insecure."

Despite feeling apprehensive at times, though, Norton still commands the screen in every scene he's in. For his neo-noir detective movie Motherless Brooklyn, the actor/director assembled a star-studded cast, including Bruce Willis, Gugu Mbatha-Raw, Bobby Cannavale, Cherry Jones, Alec Baldwin and Willem Dafoe. We sat down with Norton to discuss the movie, playing a character with Tourette syndrome, and what he made of Martin Scorsese's comments on the film industry. Here's our Q&A, conducted by Total Film editor Jane Crowther, edited for clarity.

We spoke earlier this year for Total Film magazine, and you mentioned how you paid the cast smaller rates because there was not a huge budget for this film. How did you pitch the project to them? Did you call in favours or say, “I’d like to see you, Bruce Willis, in this kind of roles”?

Honestly, it’s a little bit simpler. I just gave people the script. On something like this, you only want people who have bought into the creative opportunity of it. And happily, nobody needed a lot of pitching. They knew the deal. I’m always upfront: there’s no a lot of budget in this. But everybody said yes very quickly.

Did you always have those people in mind? Were these your first-choices?

These were people I had very much in mind, yeah. There were tonnes of people on this that were on my list of people I’d love to work with, and people who I’d come up admiring, like Willem Defoe and Alec Baldwin and Cherry Jones. But then there’s lots of people that I’ve been friends with and came up with – Bobby Cannavale and Dallas Roberts and Michael K. Williams, who I just am a fan of.

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

So it was a mutual admiration society, our cast. And it was very gratifying to feel like actors, as a tribe, can come together around a thing. And if enough of us come together on it, we can get it done.

What about casting yourself? Was that always, “Yes, I’m always going to do it”? Or did you flip-flop between whether you should star as well as direct?

It was more the flip. I wasn’t quite sure about directing it. I wanted to play the role. So part of myself was protective of that. I went through a period of wondering, after I’d written it: “Should I see if some filmmakers that I really admire would get in on it?”

But the last thing you want to do is get someone you admire, and you’re playing the role, and you wrote the script, but if you have different view on things – because then it’s like: "Whose is it?" Meditating on it a bit, it became clear that I had worked on it with a level of detail that I should just do it.

And for years, because you had this bubbling under whilst you were doing Fight Club. What do you think the difference is in the film you made now, with all the experience that you’ve had, compared to if it had just immediately come together then? Do you think you’ve made a richer and better film now?

I’d have made a more cynical film then, which is weird, because I was younger, because I’d have been more committed to the genre. Detective films are always cynical. They’re hardboile. But today, both where I am in life, and also where the world is right now, I felt much less inclined to promote cynicism, or promote apathy, or promote the idea that you shouldn’t push back against power.

So I probably would have approached the ending a little differently. But also, there’s no way I could have made this film in the amount of time that we had. In these last years, I’ve worked with Spike Lee and with Wes Anderson and with a lot of people who are extremely savvy about getting sophisticated films and productions done with modest resources.

My own playbook got much more refined for doing this, at this scale, because I didn’t want to do the small version of this. I wanted to do the big version of it.

You mentioned Spike Lee there, and people who can make these big idea films on a small time constraint and budget. Were there other directors you looked to in terms of tone or cinematography or feel?

One of the biggest pieces of the puzzle was: how do you do a period film that looks lush and deep and sophisticated and painterly, when you don’t have that much time?

And I consistently looked at [Motherless Brooklyn cinematographer] Dick Pope's work with Mike Leigh, such as Topsy-Turvy and Mr Turner and The Illusionist. I knew he’d done these all on modest schedules, and they’re some of the most gorgeous films. Mr Turner, he’d just got nominated for that, the year we did a lot for Birdman. I was seeing him around. And I was just grilling him. I was like, “That’s one of the most beautiful films.”

I thought it was shot on film. So did a lot of other people. And he said, “No, no. I did it on the Alexa, one of these digital cameras.” And I was gobsmacked by that. I thought, “My God, how is he…?”

I was looking at Dick’s work and going, “I need that. I need not just his painterly mastery, but obviously his capability of doing that on Mike Leigh’s budgets and schedules – not David Flincher’s budgets and schedules.”

You were spinning a lot of plates, directing and acting in the movie. But it’s not just a straightforward role. You play a Tourette’s sufferer, and that’s a very complex series of physical and emotional hoops to jump through. What was your process for getting that right like? How did you make sure it was something that would be recognisable to people who do suffer from the condition?

The research isn’t super-mysterious. It’s books and documentaries and meeting people and asking a lot of questions. You can get a lot of information about a thing like that very quickly, and you can get perspective from people.

But there are good documentaries about people with Tourette’s – not that it’s not even more interesting to meet people. But in a documentary, they may feature a dozen people who each have different manifestations. So you get a lot of exposure to like: “Wow, it can be like that. Wow, it can be like that.” And then that becomes interesting raw material for the grab bag of symptoms that you want to create for this character.

The trickiest thing about something like that, honestly, is that... if you’re a footballer player or something, you’ve lined up and kicked a ball 10,000 times by the time you’re 15 years old, right? It’s not something you think about. It’s an intuitive, muscle memory kind of thing. But if you’re doing something like this, you’re starting from scratch, and you don’t have a tonne of time, and you still have to get to that place. It really, ultimately, is just time. You have to create time for yourself.

It’s weird – I’ve been doing this for such a long time, but you can still get self-conscious. I wish I could say I was a person where I didn’t care who was watching. Who do you know well enough to be silly in front of and fail and paint badly and sing badly? How many people can you think of that you would take a singing lesson in front of? That’s what rehearsing something like this at the beginning is like. You have to have that zone where you can just do the scenes over and over and over again until you start to get into a thing where someone can be like, “That was interesting. I like that.”

It’s really funny. Bruce Springsteen saw the movie recently. He was really, really nice about it. We were talking about a lot of stuff, and I said something to him: "Were you always fine to be in the studio, working on songs, no matter who was there?" And he was like, "Oh my God, no. There were some times I didn’t even want the guys in the band around.' If Bruce Springsteen doesn’t want anybody around until he thinks he’s got it right, then I guess we’re all still a little insecure.

The beginning of the process – it always feels a little half-baked. I think this is true just in general. It can be starting a website or whatever.You’re faking it in the beginning. And you know in your own mind, “This is really half-baked. It’s not going to work. It feels fraudulent.”

Final question. Motherless Brooklyn is an old-fashioned film, without huge budget, special effects, or part of a franchise. It calls to mind the sort of things that Martin Scorsese has been saying recently, that he’s worried that these films might be under threat. Do you feel that? Or do you feel you can make another one like this?

I thought one of the most astute observations he made, which is just clinically true, is that one of the things that makes it the most challenging is how tough it is to keep a film in theatres. He talks about how the churn of commercial films shooting for very large opening weekends – there are so many now, and they come at such a pace, that a film that is getting a terrific response from an adult audience but needs time for the word of mouth and for the audience to keep coming – that’s just not available anymore.

And that’s tough. That’s challenging. I was reading recently about Apocalypse Now, one of the ones we’d call one of the greatest films – and it is. They put it out, and, you know, it played in the theatres for 14 months. Not 14 weeks. It played for 14 months. It was never a blockbuster, but it just becomes something you had to see, and they were able to keep it out. That isn’t in the realm of possibility. 14 weeks isn’t even in the realm of possibility anymore.

So do you think you will make another one in that sort of realm? Or is it something that you want to move away from now, and try something different?

I don’t know. It’s telling, isn’t it? Granted, Scorsese’s film is a really big film, it’s a really big budget, and that might, in particular, have made him feel like: “I don’t want to deal with the risks that tend to be with that kind of thing.” So he did it this way.

The point being: yes, of course, it’s true that it is uncertain what will work. As the business model of theatrical cinema films evolves, some things will have a harder time surviving within it. That’s been happening for a long time.

But at the same time, what I don’t feel is a fundamental lament about the whole situation. I think it’s a very, very exciting time.

Imagine you’re a 24-year-old transgender filmmaker. This is not a time to lament. This is a time to celebrate. There is more chance for that voice to get to tell a story in some crazy form that defies the two-hour film expectation. It’s a very robust time. More people are being led into the tent of storytelling. There are more formats, more audiences reaching things in all kinds of ways. And maybe that pressure of the opening weekend box office won’t be appealing to people anymore. These things shift and change. To me, that’s not a tragedy.

And that’s not to say someone like Scorsese is wrong. People make a tempest in a teapot. They treat it as though anybody thinking about these things, confers some kind of insult, because he said one thing or another. And that’s just silly. If you read it, it’s a very thoughtful commentary from one of our elder statesmen, commenting on what his relationship and his life in film has been and the melancholy that he feels about the shift.

But that’s OK. That’s OK. It’s understandable. It’s not an insult to anyone else. And also, it doesn’t mean that young people have to feel the same kind of lament. They can look at it and say, “Well, with all respect, it’s much better for me. There’s many ways for me to do it now.”

I fall right in the middle of it all. Yes, it will get harder to do these sorts of things theatrically, perhaps, but I don’t think that signals the death knell of really high-grade, sophisticated, exciting storytelling at all. Not at all.

And I think if you stay nimble and connected to why you’re telling stories, and keep looking for stories that resonate for other people, then there will always be a way, because people are hungry for it.

Motherless Brooklyn reaches UK cinemas Friday, 6 December, and is in US theatres now.

Jack Shepherd is the former Senior Entertainment Editor of GamesRadar. Jack used to work at The Independent as a general culture writer before specializing in TV and film for the likes of GR+, Total Film, SFX, and others. You can now find Jack working as a freelance journalist and editor.