Empire Of The Sun: Forgotten Masterpiece

Spielberg's first war film

Child Of War

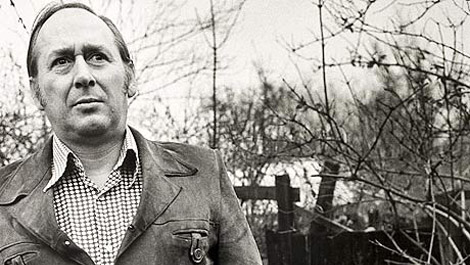

Born and raised in the Shanghai International Settlement, a foreign-controlled part of Japan where residents lived an “American way of life”, J.G Ballard’s Empire Of The Sun was written as a way of documenting the author’s childhood memories of the outbreak of World War 2.

Interned with his parents by Japanese forces after the attack on Pearl Harbour, Ballard was profoundly marked by his wartime experiences, but it would take some 40 years before he could find the words to adequately do them justice on the page.

“How do you convey the casual surrealism of war?” he would go on to muse in an article written for The Guardian back in 2006.

“The deep silence of abandoned villages and paddy fields, the strange normality of a dead Japanese soldier lying by the road like an unwanted piece of luggage?”

The novel was eventually published in 1984, with Ballard drawing from his experiences and placing them within a fictionalised framework that necessitated the removal of his parents from the story.

“My mind was expanding to fill the possibilities of the war,” he explains, “something I needed to do on my own. Once I separated Jim from his parents the novel unrolled itself at my feet like a bullet-ridden carpet.”

Survivor

While Ballard remained with his parents throughout the period, his fictional doppelganger soon finds himself cut adrift, and in increasingly desperate circumstances.

Rather than simply charting a memoir, Ballard found himself working through his feelings concerning the war and adolescence in general.

“I waited 40 years before giving it a go, one of the longest periods a professional writer has put off describing the most formative events in his life. Twenty years to forget, and then 20 years to remember. There was always the possibility that my memories of the war concealed a deeper stratum of unease that I preferred not to face.”

Once the book was published, the Pandora’s box had well and truly been thrown open.

“In 1984 the novel was published,” recalls Ballard, “a caravel of memories raised from the deep. Enough of it was based on fact to convince me that what had seemed a dream-like pageant was a negotiated truth.”

Hollywood Calling

The book was a bestseller and was critically feted across the board, winning the Guardian Fiction Prize, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and becoming shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Understandably, it wasn’t long before Hollywood came knocking.

David Lean was the first to examine the idea of adapting the property, asking none other than Steven Spielberg to secure the rights to the novel on his behalf.

Spielberg was to work as a producer on the project, with Lean directing in tandem with Harold Becker.

However, Lean eventually went cold on the idea, despite having devoted a year to pre-production.

The director decided that the story lacked the requisite “dramatic structure” to translate into a successful film, and left the project in order to direct an adaptation of Joseph Conrad’s Nostromo .

Fortunately, Spielberg retained faith in the production, and stepped into Lean’s newly vacated shoes. As he later confessed, he had “secretly wanted to do it himself” all along…

Glitz And Glamour

Having sat on the sidelines for so long, Spielberg was excited to get the ball rolling, a process that Ballard found dizzying in its foreignness.

Typically, he phrases the sensation rather more poetically than we ever could…

“Then, in 1987, like a jumbo jet crash-landing in a suburban park, a Hollywood film company came down from the sky,” says Ballard.

“It disgorged an army of actors, makeup artists, set designers, costume specialists, cinematographers and a director, Steven Spielberg, all of whom had strong ideas of their own about wartime Shanghai. After 40 years my memories had shaped themselves into a novel, but only three years later they were mutating again.”

For Spielberg, the project represented an opportunity for him to break away from his growing reputation as a director of thrilling, but slightly immature blockbusters.

“I just reached a saturation point,” explains Spielberg, “and I thought Empire was a great way of performing an exorcism on that period. I had never read anything with an adult setting … where a child saw things through a man’s eyes as opposed to a man discovering things through the child in him.”

Adaptation

Ballard’s novel was adapted into a screenplay by the playwright Tom Stoppard, having seen his own childhood thrown into turmoil by the onset of WW2.

Stoppard had been born in Czechoslovakia, but was forced to flee the country as a two-year-old when the Nazi invasion loomed large.

Stoppard sought to streamline Ballard’s narrative into a more focused, snappy accompaniment to Spielberg’s camerawork, happily reigning himself in in order to accommodate several sequences in which the director viewed dialogue as altogether superfluous.

Indeed, so successful was the partnership between Spielberg and Stoppard, that the director would go on to seek the playwright’s help when it came to lending a hand on the script for Indiana Jones And The Last Crusade .

Stoppard was uncredited on that film, but Spielberg would later claim that “he was responsible for almost every line of dialogue in the film.”

This Means War

Spielberg had long held a fascination with the Second World War, and had jumped at the opportunity to work on the project when Lean had been attached.

His favourite film as a child had been the aforementioned auteur’s Bridge Over The River Kwai , and Ballard’s story offered him an opportunity to put his own stamp on the Japanese POW story.

Spielberg’s father had worked as a radio operator as part of the China-Burma Theatre (the name used by the US army for its forces in China and Burma during WW2), and had told his son countless stories from the period during his formative years.

As a result, the conflict had become something of an obsession for the director.

“Growing up, my father regaled me with wartime stories, all of them unglamorous,” says Spielberg.

“He spoke of patriotism and the call of duty. He talked about the tedium, the typhoons, the low morale. Not the kind of things you would say would make a good movie someday.”

However, it was this nightmarish, otherworldly quality that Spielberg was keen to explore, and in Ballard’s own experiences, he found a story that chimed with the experience his father had previously described…

On Location

Spielberg was keen to ground his film in the environment in which it was set, and so it was that Empire Of The Sun became the first American film to shoot inside Shanghai since the Second World War itself.

Spielberg and his crew reportedly negotiated with Shanghai Film Studios and China Film Co-Production Corporation for an entire year before permission was finally granted.

However, once Spielberg and co. were allowed into the city, they found their hosts exceedingly helpful.

Whole blocks of the city were closed down for filming, while thousands of local residents signed up to appear as extras.

Even the People’s Liberation Army appeared in the film as the occupying Japanese soldiers.

Spielberg was keen to keep Ballard involved in proceedings, even granting him a cameo as a guest at the film’s opening fancy-dress party.

The author also accompanied the group to Shanghai, where he discovered that his memories of the place were as accurate as ever.

“Curiously, my original memories of Shanghai still seemed intact,” recalled the author, “and even survived a return trip to Shanghai, where I found our house in Amherst Avenue and our room in Lunghua camp - now a boarding school - virtually unchanged.”

Up In The Air

In addition to securing the appropriate location, Spielberg indulged the obsession of his childhood self by ensuring the aircraft featured in the film were as accurate as possible.

He commissioned a series of full-scale replicas and even oversaw the restoration of a number of old war-planes for use in the picture. Hard work, eh Steven?

Spielberg also adapted certain passages of the novel in order to reinforce the sight of aircraft as a symbol of hope and escape.

Indeed, the sequence in which Jim stands upon a rooftop staring in wonder at the American warplanes seems to have been lifted from Spielberg’s childhood rather than Ballard’s.

As a P-51 Mustang flies overhead, the world around Jim appears to stop dead and the plane passes by in slow motion.

The pilot turns to look at our young hero, and waves down at him beatifically.

For a brief moment, a lonely young boy is transported to a happier place entirely.

That isn’t quite how the scene plays out in the book, but by drawing upon his own childhood fascination with warplanes, Spielberg creates a powerful sense of Jim’s fleeting ecstasy.

It’s an extremely memorable scene.

Open Your Eyes

Empire Of The Sun is a markedly visual film, with many of its most significant scenes operating entirely without dialogue.

It has been suggested that the opening half an hour or so could exist as a silent movie, and indeed, the striking canvasses that Spielberg sets about painting live long in the viewer’s memory.

It was a style of storytelling that director would later claim he had picked up upon during his reading of the novel, which according to Spielberg, “made selections of what a child grabs onto with his eyes compared to what an adult chooses to look at.”

As a result, he set about attempting to portray the world through the eyes of a child, stripping back the dialogue in order to facilitate this approach.

As a result, there is a very clear sense of bewilderment that runs throughout the movie, as Jim attempts to make sense of a period in world history that even the most experienced of men would be bemused by. Ballard’s “casual surrealism of war” is writ large for all to see.

Textual Chemistry

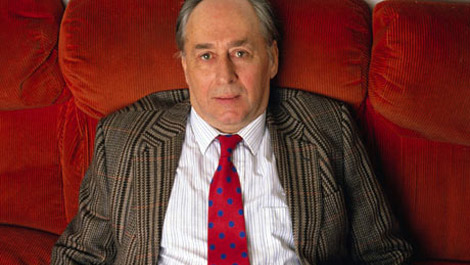

Ballard would go on to describe Spielberg as “an intelligent and thoughtful man”, and his interpretation of the original material has often been held up as a source of praise.

As mentioned previously, the director’s mastery of the visual was particularly evident in the film’s opening segment, which screenwriter Tom Stoppard would later describe as being “somewhere in the masterpiece class”.

However, what was particularly perceptive was his summation of how the events of the book should be treated with a pinch of salt. Spielberg argued that, “half of what happened, happened [ in the narrator’s head ]”, and was continually aware of the need to cloud some of the film’s events with an air of uncertainty.

The middle section is admittedly ponderous ( the trade-off involved with fleshing out some of the supporting players), but outside of that sequence, Spielberg does a fine job of maintaining the fluid nature of proceedings, with so many events crammed into Jim’s experience that one can’t help but question how much of it is simply the product of his imagination.

Family Affair

As is so often the case with Spielberg, the significance of the family unit is at the heart of Empire Of The Sun .

However, in this case, the presence of the Beard’s favourite theme is felt through its very absence: Jim’s family are nowhere to be seen for much of the film’s running time.

While Ballard wrote his parents out of the story in order to create a more compelling, streamlined narrative, Spielberg uses their absence to further explore the theme of the loss of childhood innocence.

“My parents got a divorce when I was 14, 15,” he explains. “The whole thing about separation is something that runs very deep in anyone exposed to divorce.”

Spielberg has described the film as the counterpoint to Hook – innocence is dispensed with rather than rediscovered.

Yes, Jim is reunited with his parents at the end, but this isn’t presented as a conventional happy ending.

Jim is initially indifferent when his mother approaches him, and when he eventually recognises her, he closes his eyes in a kind of surrender.

It may not be as bleak as Ballard’s ending, but coming from a director famed for family-orientated narratives, it’s an interesting diversion from the norm.

A Star Is Born

One of the most remarkable elements of the film is the startlingly composed performance of a young Christian Bale, who was just thirteen years old at the time the movie was shot.

And while working with Spielberg on such a large-scale production might have terrified most teens, Bale claims that he took the whole adventure in his stride.

“I'd nothing to lose,” begins Bale. “I wasn't thinking in terms of a career. I wasn't really thinking about the consequences at all. I tend to think you're fearless when you recognize why you should be scared of things, but do them anyway. I didn't recognize it that time.”

Indeed, Ballard recalls an encounter with the young Bale, in which the film’s leading man comes across as anything but shy.

“There was a brilliant child actor, Christian Bale, who uncannily resembled my younger self,” recalled Ballard. “He came up to me on the set and said: ‘Hello, Mr Ballard. I'm you.’”

That said, suddenly parachuting into the Hollywood limelight did have the odd drawback for the young Bale.

“Suddenly people were saying I was cocky because I'd done a Steven Spielberg movie... I suddenly started feeling like a freak because everyone was treating me differently. It was confusing, and I did wonder if acting was for me anymore.”

Fortunately, he came around soon enough…

Early Reactions

Despite the common conception that the film was panned upon its release, Empire scored well with many reviewers, despite taking a few critical brickbats along the way.

Ballard himself recalls a fairly rapturous reception at the film’s official premiere, having been pleasantly surprised that the glamour of the evening did not detract from his story’s message.

“Surprisingly, it was the film premiere in Hollywood, the fount of most of our planet's fantasies, that brought everything down to earth,” says Ballard. “A wonderful night for any novelist, and a reminder of the limits of the printed word.”

“Sitting with the sober British contingent, surrounded by everyone from Dolly Parton to Sean Connery, I thought Spielberg's film would be drowned by the shimmer of mink and the diamond glitter. But once the curtains parted the audience was gripped. Chevy Chase, sitting next to me, seemed to think he was watching a newsreel, crying: ‘Oh, oh . . . !’ and leaping out of his seat as if ready to rush the screen in defence of young Bale.”

That said, the film was undeniably a financial flop by Spielberg’s standards.

Empire took just $22.24 million in North America, before eventually covering its budget with a $66.7 million global haul. Jurassic Park , it was not…

Oscar Night

Despite mixed reviews from the critics, Empire Of The Sun did receive a degree of acclaim from the Academy, albeit only in the technical categories.

The film was nominated for Cinematography, Art Direction, Editing, Original Music Score, Costume Design and Sound, but failed to win a statuette in any of those disciplines.

Cinematographer Allen Davieu spoke out of his incredulity that Spielberg himself had been snubbed.

“I can't second-guess the Academy,” he exclaimed, “but I feel very sorry that I get nominations and Steven doesn't. It's his vision that makes it all come together, and if Steven wasn't making these films, none of us would be here.”

However, the film did go on to score BAFTAs in Cinematography, Sound Design and Musical Score, and Christian Bale was recognised by the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures, who created an award for Best Performance by a Juvenile Actor specifically to honour his contribution.

Seal Of Approval

Despite the Academy’s public snub, Spielberg could at least bask in the approval of the one man whose opinion really counted above all others: J.G. Ballard himself.

“I liked the film,” said Ballard in 2006. “I think it is a very impressive piece of work. I see it once every couple of years. … It seems to have got richer and more interesting as the years pass. I see it not as the film of my book but a film in its own right.”

However, there was an inevitable note of wistfulness at the way his memories have now become mingled with the creative juices of another artist.

“I was deeply moved by the film but, like every novelist, couldn't help feeling that my memories had been hijacked by someone else's,” explains Ballard.

“Actors of another kind play out our memories, performing on a stage inside our heads whenever we think of childhood, our first day at school, courtship and marriage. The longer we live the more our repertory company emerges from the shadows and moves to the front of the stage.”

“Spielberg's film seems more truthful as the years pass. Christian Bale and John Malkovich join hands by the footlights with my real parents and my younger self, with the Japanese soldiers and American pilots, as a boy runs forever across a peaceful lawn towards the coming war. But perhaps, in the end, it's all only a movie.”

Forgotten Masterpiece

Even years after its release, it still feels as though Empire struggles to gain the respect it deserves. While much of Spielberg's canon is discussed ad nauseum (and rightly so in the majority of cases), Empire Of The Sun seems to have slipped through the cracks, unfairly dismissed in favour of some of the Beard's more accessible efforts.

Even in comparison with his other war films, Empire is rarely discussed in the sort of hushed tones as Saving Private Ryan , a film heavy on bombast but arguably more simplistic than his earlier exploration of WW2. To our minds however, it stands up alongside his very finest films, and is deserving of a second look from those who might previously have passed it over. Give it another go. We're sure you won't be disappointed.

George was once GamesRadar's resident movie news person, based out of London. He understands that all men must die, but he'd rather not think about it. But now he's working at Stylist Magazine.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!