25 years after its release, The Blair Witch Project co-director takes a deep dive into found footage cult hit and shares an obscure Star Wars inspiration

Exclusive: Eduardo Sánchez breaks down The Blair Witch Project with Total Film magazine

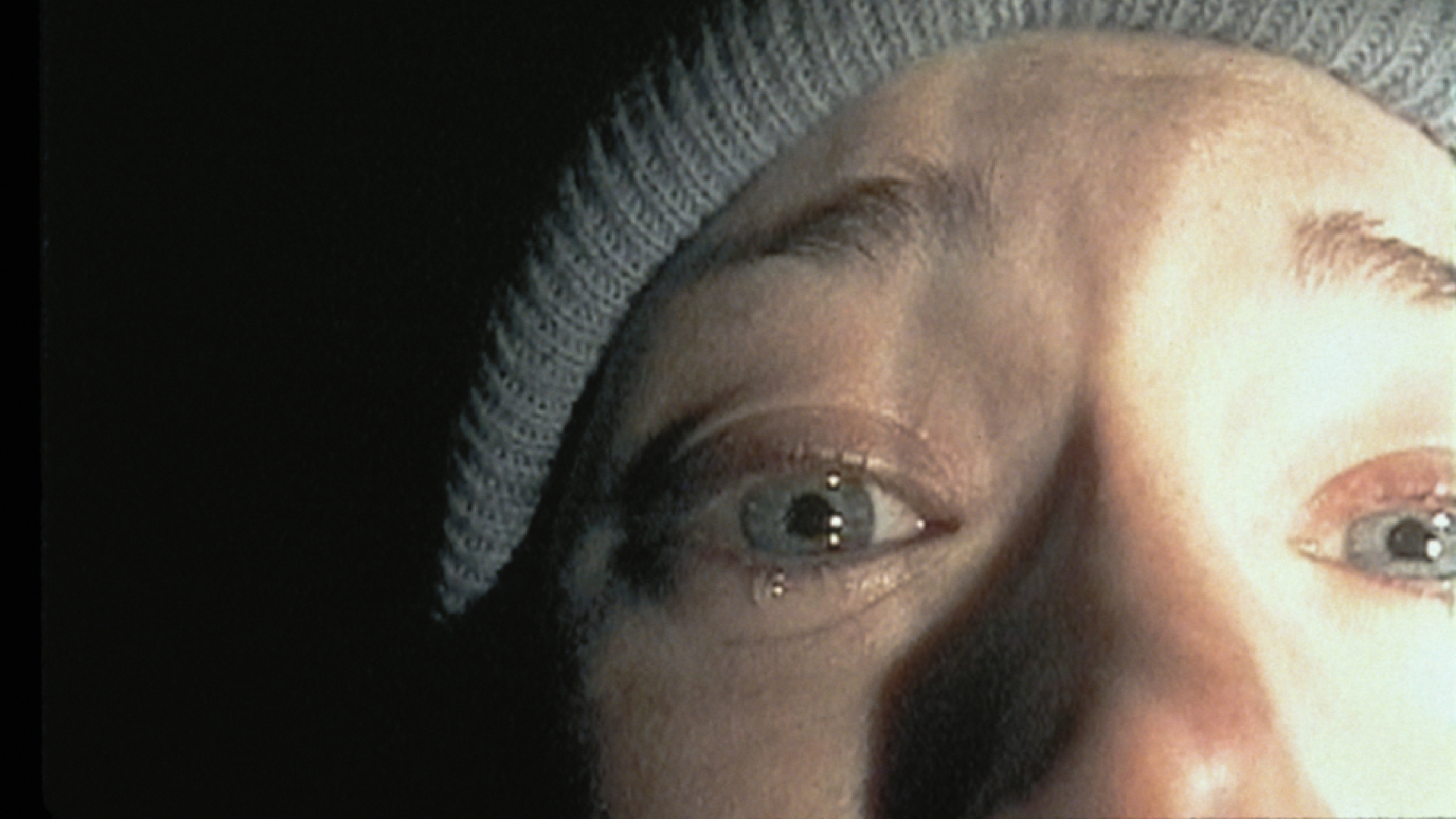

In 1999, The Blair Witch Project scared the world. "It was so profoundly terrifying that I didn’t watch it again for another decade," Host director Rob Savage remembers. Co-directed by duo Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick, who met during university, it signalled the arrival of an untapped style of genre filmmaking and shocked [Rec] co-director Jaume Balagueró "because it was a completely new approach to horror".

The faux-doc horror follows a filmmaking trio who venture into Maryland’s Black Hills Forest in pursuit of the mysterious ‘Blair Witch’; only their tapes are ever recovered. "I just remember it was all anybody wanted to talk about for, like, two weeks straight," Deadstream co-director Vanessa Winter recalls. But no one was more terrified of the movie than co-director Eduardo Sánchez: "How do you follow The Blair Witch Project?"

Although Sánchez grew up on a diet of classic '70s horror, it was the pseudodocumentary shows In Search of… (hosted by Leonard Nimoy) and Unsolved Mysteries that truly got under his skin. But before Cannibal Holocaust, even before COPS, Sánchez’s number one inspiration for found footage? Bigfoot. "For me and Dan, the Patterson-Gimlin film was the impetus for us to get into found footage. That film was the creepiest thing we’d ever seen." These cinema-verité documentarians, alongside Sánchez’s lifelong uneasiness around the deep wood, inspired the stew of ideas for what would eventually become The Blair Witch Project.

In The Blair Witch Project a lingering malevolence hangs over the film. Even as Sánchez cranks up the horror, there’s a purposeful ambiguity and control – something he learned from Spielberg. "In Jaws, you feel its presence from the beginning – but you need to tease the shark. It’s everything else that warns you of the danger, like John Williams’ score." The next time you watch The Blair Witch Project, close your eyes for a moment and just listen. Every sound is purposeful – a mandate from the directors that everything the audience can see and hear be authentic to the woodland setting. That is, apart from the unsettling sounds of children distantly playing through a boom box (recorded by Sánchez’s mother) and the sinister effigies of sticks and stones scattered around. "The iconography of the weird things in the woods – still so iconic, and still so scary," Watcher director Chloe Okuno tells TF.

The Blair Witch Project opens with interspersed interviews featuring Burkittsville locals, their seductive naturalism a clever ploy from Sánchez and Myrick that immediately cements the authenticity of its world. "The interviews are a big part for me – you start to believe you’re interacting with real people. It’s super-brilliant," Winter says. The actual shoot only took eight days in total, with over 20 hours of footage shot entirely by the trio of actors Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams and Joshua Leonard – Donahue had never even operated a camera before working on the film. "You definitely couldn’t shoot the actors for the full 24 hours like we did back then any more," Sánchez notes. To create a sense of isolating immersion, the pair directed from afar, leaving clues in milk crates the trio had to find using their GPS, only interacting with them directly during nightfall, to keep them from sleeping.

For Radio Silence duo Matt BettinelliOlpin and Tyler Gillett (Scream, Abigail), that immersive direction creates the film’s magic: "You have these wildly visceral performances that would hold up in any style of movie; they just happen to exist in this very lo-fi, handheld film," Gillett says. That, coupled with the deliberately unprofessional and grainy nature of Heather’s video footage, hammers home the upsetting authenticity that found footage can achieve. "That’s the haunting promise of found footage – the less you know, the more it grows. Found footage lives or dies by that mantra," Sánchez maintains.

Going viral

Although production ended, the worldbuilding did not. A year before the film’s release, Sánchez and crew set up a website documenting the disappearance of the ‘real’ filmmakers, including police evidence, crime-scene photos and extracts of Heather’s bloodied and aged diary. "It’s very exciting because it’s all based on other things that aren’t in the movie but have their own personality. That’s very powerful," Balagueró remembers. This internet-led storytelling approach was groundbreaking at the time and was the key to Blair Witch’s phenomenon status. Sánchez remembers Jeff Johnsen, a champion of The Blair Witch Project, even appearing on an LA morning talk show and going through the website to explain it all. "The traffic for the website blew up that same month," the director says.

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Sánchez’s idea for the website came from his love of Lucasfilm’s Shadows of the Empire, which used other forms of media – including a book, comics and a videogame – to create a story set between Episodes V and VI. "I loved this concept, that it wasn’t even centred around a movie. You had this whole universe centred around just an idea that kept expanding." This ambitious storytelling is something Sánchez has utilised throughout his career, from 150-page story bibles on sci-fi thriller Altered to whole transmedia shooting units on Lovely Molly.

After previewing snippets of footage at smaller festivals to gauge reactions, the film premiered at Sundance in January 1999, with Park City blanketed by ‘missing person’ posters featuring the cast. Indie distributor Artisan Entertainment picked up the film, another key moment for The Blair Witch Project. "I don’t think Blair Witch would’ve been handled the same way by any other company," says Sánchez. Artisan, however, wanted to change the unforgettably unsettling ending in which Heather discovers Michael in the basement, facing the corner, but ultimately the directors won out. "The middle, that ambiguity, is where fear truly lies."

The film opened in just 27 cinemas on 14 July 1999 and made $1.5 million, scaring off Eyes Wide Shut with a per-cinema average more than six times that of Kubrick’s highly publicised erotic thriller. Bettinelli-Olpin and Gillett remember being in packed cinemas and dorm rooms, transfixed: "It just felt like there was something different and magic happening that was wildly unique," says Bettinelli-Olpin. When the film went nationwide two weeks later, it made $29.2 million. By the time it ended its theatrical run, it became the 10th highest-grossing film in the US that year, beating Notting Hill, Stuart Little and even The World is Not Enough in the US, and taking in $250 million worldwide. "It was such a cultural moment, it really anticipated so much of what is popular now," Okuno recollects.

The Blair Witch Project seemed to electrify everyone who came into contact with it – except Sánchez and Myrick. "I think due to the pressures of having such a success, and also the pressures of being a duo, co-directing and essentially co-birthing this movie together, my relationship with Dan started to break down." Sánchez even remembers a time when a former agent asked him which one of them actually had the filmmaking talent. Artisan wanted to capitalise on the phenomenon, but Sánchez and Myrick’s desire not to be pigeon-holed as the ‘found-footage guys’, alongside their eroding relationship, made them decline a follow-up. ‘Honestly, we would have probably signed on, but they had a release date before they even had an idea,’ the director says. "Everyone knows it’s not a good idea to set a release date and then come up with a movie."

Lost and found

The Blair Witch… led to a lot of other projects being offered the duo’s way, including the chance to helm the J.J. Abrams-penned 2001 horror-thriller Joy Ride. ‘We went down the road a little bit,’ Sánchez says. ‘I liked it but Dan didn’t, so we passed.’ Abrams would eventually go on to create his own found-footage monster hit Cloverfield with Matt Reeves in 2008, which Sánchez humbly cites as the true galvanisation moment for found footage: "It opened the door for everything, and it’s been really exciting to see the evolution of found-footage movies since."

Of all the early 2000s horror movies released, Sánchez believes he read ‘90%’ of the scripts, and had offers to direct a quarter of them. But with a lack of a clear mentor, the difficulty of convincing two filmmakers to unite on one project, and the pressure of following up one of the most successful independent films of all time, Sánchez stepped away from filmmaking entirely. "Honestly, I was scared. I felt like I didn’t know how to handle a big movie."

Sánchez retired from filmmaking for six years until sci-fi thriller Altered, in which a motley crew seek revenge on the alien that killed their friend. Despite a huge blow from a change in Altered’s release plans due to executive departures at the distributor, Sánchez powered on, his filmmaking desire rekindled. He flirted with found footage on Lovely Molly before finally returning in full to the style with Bigfoot creature feature Exists and V/H/S 2 short A Ride in the Park. "It was just so fun to get back into it, see how we could update it and have fun with it. We loved seeing how people had evolved the style, and that the emphasis was on scaring the crap out of you instead of convincing you it was real."

Sánchez is even developing a new project he describes as ‘our own new version of found footage’, noting that – as with The Blair Witch Project – he’s experimenting as much as possible. Found footage has now come so far since 1999, with many directors having evolved the style bit by bit – what does the future of found footage look like to them?

"The playground is bigger and the technology is more accessible than ever. What I’ve always loved about found footage is it’s not story-based, it’s style-based," says Sánchez. This foundation of style is why Bettinelli-Olpin and Gillett boarded the V/H/S franchise as producers: "There’s the opportunity for new voices to emerge and go, 'Oh, that’s a good point of view I haven’t seen before'," says Bettinelli-Olpin. Chloe Okuno agrees that opportunities like the V/H/S franchise open doors for aspiring filmmakers. "It’s such a good way to allow them to deliver something that’s like their pure vision."

This accessibility alongside a now nearendless stream of footage is something Rob Savage believes is the key to its evolution. "There’s an opportunity to do what Blair Witch did in the 90s now with live streaming and the way we digest stories." The internet’s growing prevalence in found-footage stories – Spree, Dashcam and Deadstream being recent examples – suggest perhaps footage is no longer found, but lived. "The genre is remaking itself, there’s this consideration of what other levels we can take in terms of scares and entertainment," Winter adds.

Recently, Blumhouse announced their own plans to resurrect The Blair Witch Project, hoping to scare a whole new generation of moviegoers with a brand-new take on the horror. The question is, how do you improve a film many believe was perfect the first time round? "It’s one of those definitive of-an-era movies," Gillett says. "There’s a simplicity that will never be matched," Savage adds. What does Sánchez make of his film’s legacy? "Man, just the possibility these talented filmmakers were even slightly inspired – it’s just really fun to see where it’s gone and where it’s continuing to go."

The Blair Witch project is currently available to stream on BBC iPlayer. For more scares, here's our guide to the best horror movies and all the upcoming horror movies to add to you calendar.

You can read more from Total Film in our latest issue, which is out on shelves now.

Sab is an Entertainment and Culture journalist based in London, whose bylines include Polygon, Rolling Stone UK and Metro. After graduating from university with a degree in Film Studies, he stepped into the world of film and video games journalism, focusing on in-depth stories and studio & individual profiles. When he's not playing interactive dramas like As Dusk Falls, he's usually adding films to his never-ending watchlist or trying to catch-up on his ever-increasing game library.