Fable 4 might be a new beginning, but here are five lessons it should learn from the original game

What is a fable if not an old story, retold for a new audience?

We all just assumed it was going to be called Fable 4. We had, in fact, been unofficially referring to PlayGround Games' next project as just that as soon as rumours surfaced that the Forza studio was working on new upcoming Xbox Series X games. Then the Xbox Series X first-party reveal event happened, and it confirmed that the next-gen Fable game is just that... it's Fable. No number. Like the first one, but again.

Fine. If this Fable for Xbox Series X and Xbox Series S really is to be a "new beginning for the legendary franchise", as Microsoft describes it, then it makes sense to return to the source – Lionhead Studio's 2004 original – to find out what the legendary Xbox RPG can still teach us (and Playground) about the Guild of Heroes.

Centralise the adventure

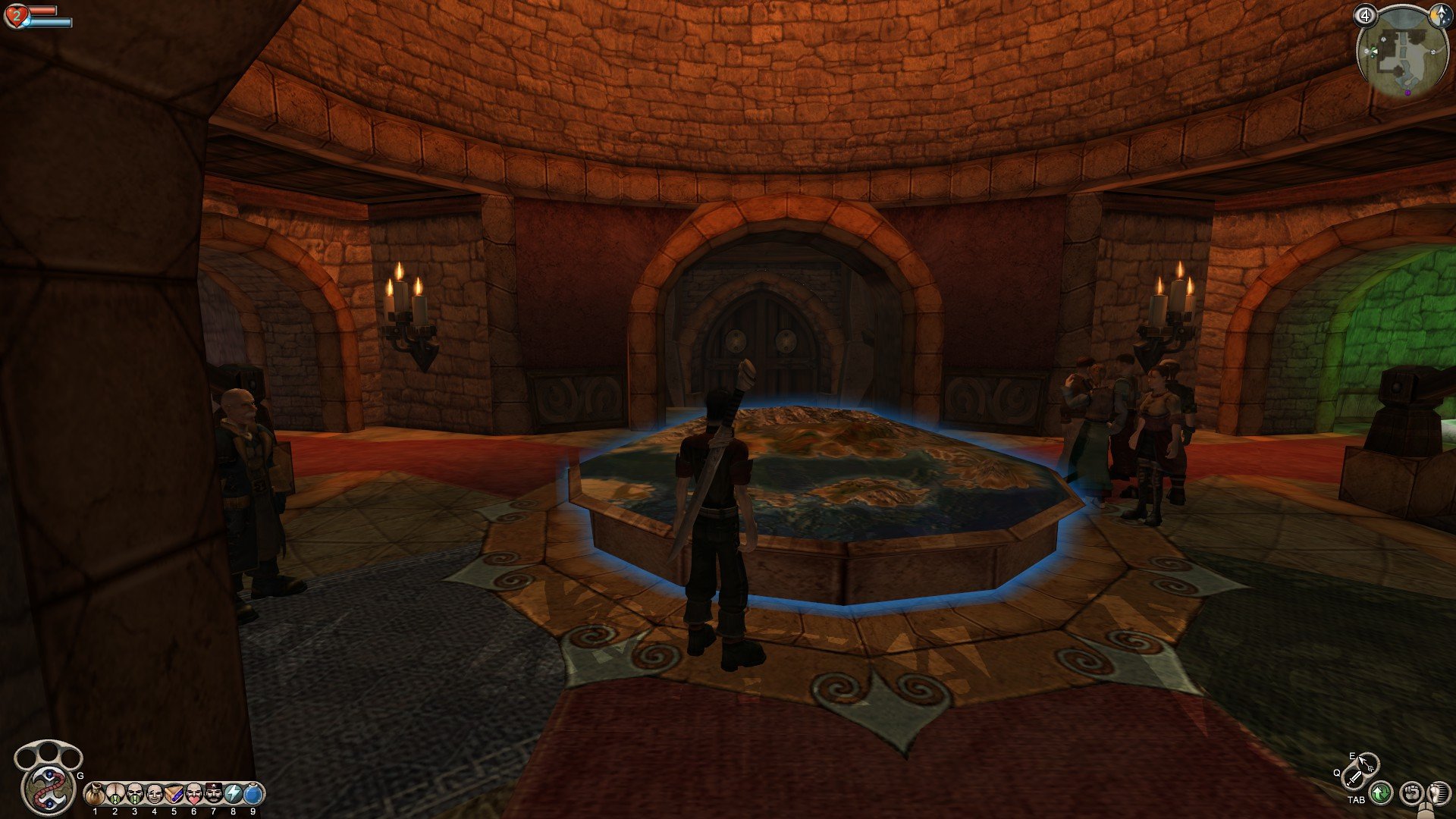

In theory, Fable works like any other RPG of the period – it has a large, interconnected world which you can explore on foot, gradually learning the layout of towns and tentatively exploring the wilderness in between. In practice, though, you regularly teleport back to the Guild of Heroes, the hub where you level up your character and select your next quest.

The Guild is less like a Witcher training academy and more an agency that connects freelance fighters with clients – farmers who need a barn protecting, or traders escorting goods from A to B. They're not particularly fussed about legality, and operate on a first-come-first-served basis – sometimes you get back to the Guild to be told that all the best jobs have already been nabbed from the board.

It's a satirical gig economy that’s ripe for revival today. And more than that, it's a really solid structure for a game: where many RPGs can be too intimidating or confusing to return to after a long break, you always know where you’re supposed to go next in Fable – back to the Guild, to check the map and find out who needs a job doing.

Create a believable world

Fable is often remembered as the comedy RPG, and that's not a false memory – within minutes of arriving in Oakvale, you're cornered by a guard doing his finest Holy Grail John Cleese impression, a clipped-yet-pouty delivery that lets you know you're living in a daft, parallel Britain. But Lionhead was very disciplined about where that comedy came out. While side quests and dialogue with villagers were fair game, the main plot was off-limits. Fable certainly has funny bones, but it has an earnest heart.

That, ultimately, is what distinguishes the series from less successful RPG parodies like The Bard's Tale, released the same year. Fable believes in its own world, and that lets you believe in it too, investing in its characters and real estate.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Bring back emotes

Before Fable, emotes were the preserve of multiplayer games – a way to express thanks and frustration in shooters, and to '/dance' the night away in MMOs. They tended not to have any mechanical impact, existing only in the communicative layer where players created their own meaning.

Fable’s innovation was to make the emote a primary part of a single-player game. The belches and giggles are silly, yes – but expressions are also a significant expansion of your protagonist's verb set. Where most of Fable's peers limited you to either talking or killing NPCs, expressions let you interact with characters in a systemic and, dare I say it, nuanced fashion. They even feed into your moral alignment, confirming once and for all that farting is inherently evil.

In recent years, other series have pushed the expression game forward. Watch Dogs 2's emote wheel allows you to taunt NPCs, starting fights that prompt other nearby NPCs to call the police, triggering a cascade of unpredictable AI behaviour. Animal Crossing: New Horizons has mastered the emote as a collectible, rewarding extended play with an expanded set of animations. The stage is set for Fable to reclaim the emote with its trademark theatrical flourish.

Fight with the carrot, not the stick

Okay, so it's literally true that Fable hands you a stick as your very first weapon. But the point is that it doesn’t punish you for being a bad fighter. That's unusual: games have long taught through failure, and that approach has especially been in vogue since Dark Souls – FromSoftware repeatedly knocking you down so that the eventual, deserved victory is all the more satisfying.

It's refreshing, though, to play a game that would rather reward than penalise. Fable's combat multiplier grants you bonus XP for finishing fights without taking a hit, pushing you to master its dodge, block and knockback mechanics. But if you don't feel like engaging with all that, it's happy for you to bumble through anyway, making the series approachable in a way other RPGs are not.

Don't hide the tutorial

Contemporary AAA games have made an art of teaching you mechanics as smoothly as possible, integrating tutorials into story scenes so subtle that you might not even realise you're learning.

Fable does the opposite, explicitly taking you through childhood and the multi-stage training process that turns you from tragic orphan to revenge-fuelled warrior. Much of the early game takes place in makeshift arenas and on shooting ranges where you hit straw dummies with arrows and bolts of lightning.

It's a decision that makes for a long intro. But it helps the fiction, making sense of your level one competence as an adult. And Lionhead squeezes as much value out of the conceit as possible - grading you for every class, and letting you repeat them to achieve higher marks. Players love doing that: think of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare's SAS obstacle course a few years later, and how many of us spent hours chasing new best times.

Like a lot of Fable’s lessons, the tutorial flies in the (arse) face of modern thinking. But it taps into what makes the series special: an open-armed embrace of players at every ability level, and a choice to extract as little or as much depth from it as you want, so long as you’re laughing.

For more, check out all the biggest upcoming games of 2020 on the way, or watch one of our latest episodes of Dialogue Options below.

Jeremy is a freelance editor and writer with a decade’s experience across publications like GamesRadar, Rock Paper Shotgun, PC Gamer and Edge. He specialises in features and interviews, and gets a special kick out of meeting the word count exactly. He missed the golden age of magazines, so is making up for lost time while maintaining a healthy modern guilt over the paper waste. Jeremy was once told off by the director of Dishonored 2 for not having played Dishonored 2, an error he has since corrected.