Fallout's cheery American apocalypse helped me stop worrying and love the bomb

"The entire west face of the house was black, save for five places. Here the silhouette in paint of a man mowing a lawn. Here, as in a photograph, a woman bent to pick flowers. Still farther over, their images burned on wood in one titanic instant, a small boy, hands flung into the air; higher up, the image of thrown ball, and opposite him a girl, hand raised to catch a ball which never came down".

This stark image comes from Ray Bradbury’s There Will Come Soft Rains, a short story published in 1950. In it, the blackened house continues to tick hopefully with gadgets, cleaning and cooking and obediently popping slices of toast for a family long obliterated by a nuclear blast.

It reminds me of Fallout 4. The game's opening takes place in a similarly immaculate kitchen, with gleaming surfaces and helpful robots, but it goes deeper than that. The family in Bradbury’s story are stencilled onto the side of their home, suspended forever in ignorant distraction. For me, Fallout represents a similar thing, but on an exhaustive scale, the obvious difference being that in Bradbury’s story there are no vaults to escape to. The family never returns, the house succumbs to fire and even the family dog, now thin and desperate, dies on the parlour floor. Fallout instead presents a world which holds its breath and somehow emerges from the irradiated pools with its values intact. And just like Bradbury’s doomed nuclear family, who I imagine as shadows of slicked hair, perfect smiles and buoyed skirts, those values are as American as apple pie and rayguns.

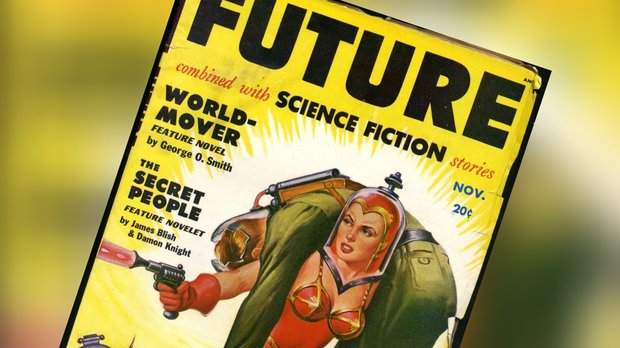

You might justifiably ask why made-up laser guns should be considered American. For me, rayguns evoke dauntless science heroes and, more pertinently, lurid pulp covers. In the early 20th century the proliferation and popularity of pulp magazines inspired a new generation of mainly American science fiction writers, including the excellently-named Futurians: a New York-based group which included Isaac Asimov, Donald A. Wollheim and Frederik Pohl.

Pulp magazines helped shape a uniquely American framework for speculative fiction, one which manifestly informs Fallout’s world: from the shady Mister Burke to the Mothership Zeta expansion, which sees a primitive human hero outwitting nefarious aliens - a classic pulp sci-fi trope, played completely straight. Pulp is also an inherently enthusiastic medium. As Boston-based pulp historian Jess Nevins writes in his excellent primer: “As a term of aesthetic and literary judgment "pulp" applies not to a genre, but to the approach of the pulp writers and magazines: an emphasis on adventure...simple emotions strongly expressed; and good always triumphing over evil.”

Fallout admittedly lets players choose their own moral trajectory, but that positivity defines the series. Yes, the world has turned to dust and monsters and squirrels on sticks, but it retains the post-war optimism and aspirational beliefs of modernist, 1950s America. It’s unlikely that things can ever be fixed, or that life can truly go back to how it was before the bombs hit, but abandoning progress would be worse than trying and failing. Vain hope is better than none.

Maybe it’s because the worst has already happened. In Fallout’s alternate history, the transistor doesn’t exist, so vacuum tubes and atomic physics became the mainspring of scientific development. As well as being locked in technological stasis, culture doesn’t advance past this period. Unlike in our history, nobody in Fallout spends years living under the shadow of the bomb, learning to fear science and question whether the pursuit of relentless advancement is actually a good thing.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Armageddon arrives before people have a chance to become skeptical, and in that sense postmodernism never gets the opportunity to exist: great news for philosophy professors; bad news for anyone who thinks handheld nuclear weapons are a shitty idea. Instead of spending 50 years frayed by the relentless, ticking Doomsday Clock, in Fallout it’s already five minutes past midnight. The world is desolate, yet people maintain faith in the systems which caused it. (In real life it’s three minutes to midnight, if you’re curious. Have a great day!)

This paradox helps explain why Fallout’s inhabitants remain upbeat despite radiation and mutant crabs, and also why so many characters in the series feel like classic pulp science heroes. The relentlessly chipper Moira Brown from Fallout 3 is a wonderful example. She’s more inventor than scientist, but her hungry pursuit of knowledge personifies Fallout’s obsession with progress and discovery.

With the help of the Lone Wanderer, she completes the Wasteland Survival Guide, documenting the dangers for coming generations. In fact, pursuit of knowledge creates the narrative framework for all of Fallout 3. The Lone Wanderer’s parents are the lead scientists behind Project Purity, an initiative designed remove radiation and provide clean drinking water to the entire Capital Wasteland. You can even follow in their footsteps with the Daddy's Boy/Girl Perk, boosting your Science and Medicine stats.

My experience of Fallout 3 echoes this, but in a different way. My Lone Wanderer was a homemaker without a home, patrolling the Capitol Wasteland with a proliferation of labour-saving gadgets. In her case, those gadgets were pneumatic power fists and a Pip-boy, rather than vacuum cleaners and washing machines. Science in the 1950s became more than just an abstract concept. Appliances replaced drab chores with mechanised wonder. Suddenly, a whole generation of women traditionally fettered to the role of housewife had the time and freedom to pursue their own goals, rather than just facilitating their husbands’.

For this reason, or perhaps because sniping super mutants while dressed in a sundress never stopped being funny, playing as a woman felt like an obvious fit. Every RPG character I’ve ever made has been in some small way a part of me, but Fallout felt like the right place for someone else’s story. Someone in a handsome bonnet, who punched off ghoul heads with metal fists.

This sums up Fallout for me. A world of science heroes, silliness, gadgets and burgeoning feminism, powerfully ignoring the surrounding despair. Conceptually, it’s the most American thing imaginable; an hollow echo of a lost dream, certainly, but also the promise of progress. You might not be able to get clean water, but look! Instant mash! I’d love to say as white, British male, being a woman in Fallout helped my understand America, but it really didn’t. As better men than me have written, the British are more comfortable with a doom that involves jumpers, and nice cups of tea, and sighing because everything’s bloody well dished. Instead, my character was like the wife in There Will Come Soft Rains; the distant image of a happier time, impressed onto a slowly crumbling world. Harder to relate to, but easier to see.