Four solodevs weigh up the risks and rewards of creating games as a team of one

Interview | Edge sits down with Tomas Sala, Lucy Blundell, Madison Karrh, and Joe Richardson

With the unprecedented wave of layoffs the game industry faced in 2023, more developers than ever before are wondering whether they can make it on their own. Surely, the thinking goes, striking out alone must beat toiling away for an employer that might not even want you sticking around once your current project has shipped. But does the reality stand up?

To find out, we talk to four solo developers to discover their experiences. Tomas Sala quit the company he founded to make The Falconeer; Lucy Blundell abandoned a career at Chillingo to create the acclaimed visual novels One Night Stand and Videoverse; Madison Karrh only found enough stability to leave her job making medical simulators with her third game, Birth; while Joe Richardson, creator of The Procession To Calvary, has only ever known solo development. How lonely is it to make games without a team in support? What kinds of compromises – artistic and financial – are required? And is all the risk worth it to be master of your own destiny?

Tomas Sala

This feature originally appeared in Edge Magazine. For more fantastic in-depth interviews, features, reviews, and more delivered straight to your door or device, subscribe to Edge.

Tomas Sala clearly has no regrets about leaving behind the corporate cage he helped to build. "I hate fucking Scrum and Trello, all this fucking Jira," he spits. "It drives me up the wall."

After co-founding Little Chicken Game Company in Amsterdam with his brother and two others in 2001, Sala spent the next decade and a half building up the firm, which at one stage employed around 30 people. The company mostly took on work-for-hire jobs, which Sala says helped him to build up his skills by working on a wide range of projects. But he didn't like being the boss, didn't like having to constantly organise a team of people. "I am incredibly chaotic," he admits.

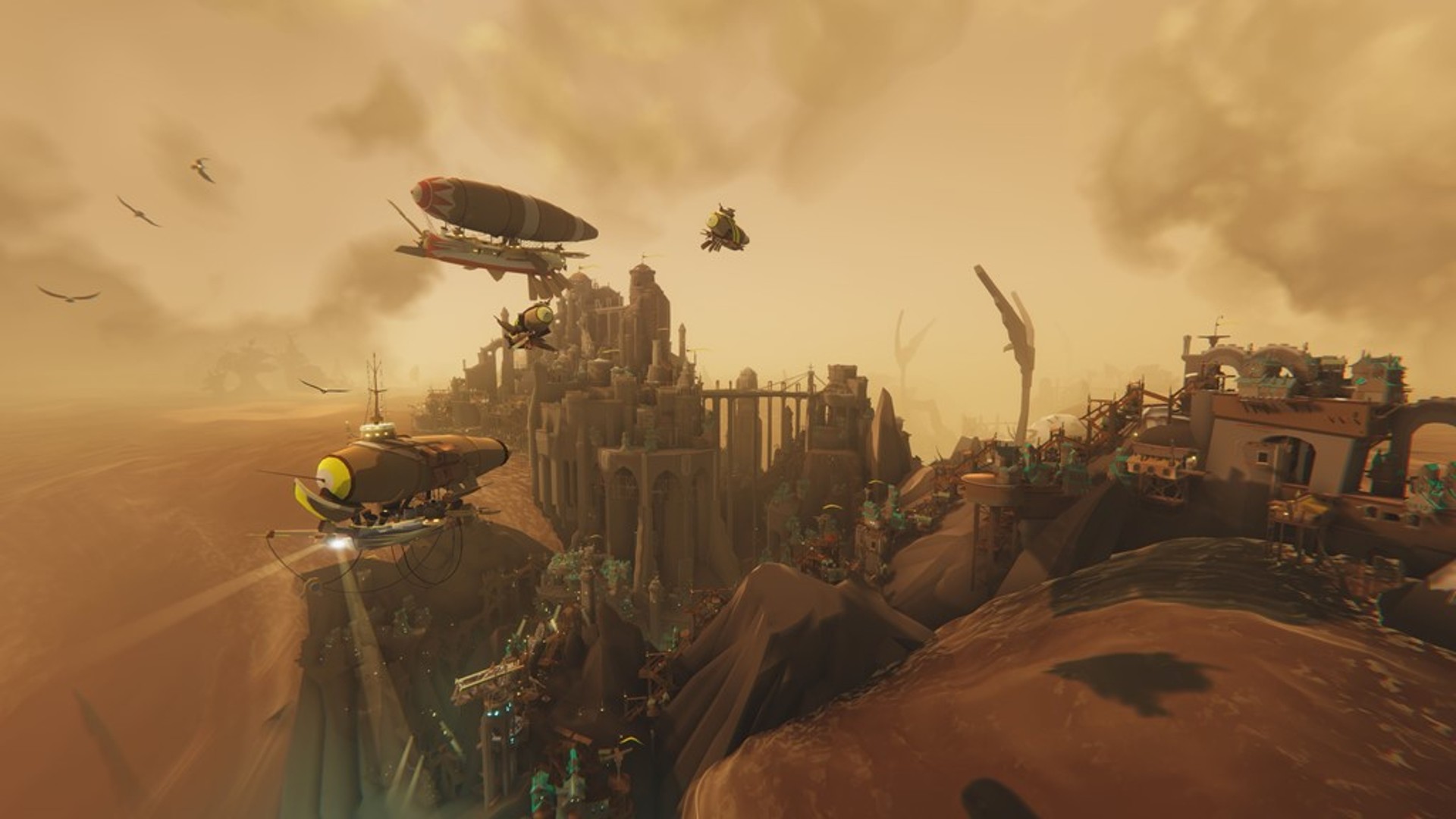

Sala started making mods to decompress, eventually releasing the Skyrim-based Moonpath To Elsweyr in 2017. It was received well enough to encourage him to start work on a game of his own, called Oberon’s Court. Sala's wife, Camille, pointed out how the darkness of Oberon's Court reflected the burnout he was experiencing at the time. The realization prompted Sala to rip up the project and build something entirely different using the assets he'd created. The Falconeer, a breezy aerial combat adventure inspired by Crimson Skies, was the result. It's tempting to see it as a reflection of his flight from the corporate world.

It's certainly a freedom in which he has revelled. Sala believes that boiling game development down into a list of tasks, as encouraged by project-management tools such as Jira, can turn what should be a creative adventure into a slog. Instead, he prefers exploring, chasing "that subconscious flow" in the manner of "creators outside of games who aren't stuck to that Jira fucking pegboard". Though Sala insists he is "quite disciplined" and keeps track of the things that need to be done in any given week, he also allows himself the room to deviate from that path when inspiration strikes. Such as waking up with the idea of making flying eels with guns, for example, and then diving straight in to create it. "I love feature creep," he says. "It's my entire design philosophy."

My only response when things get stressful is to work harder

Tomas Sala

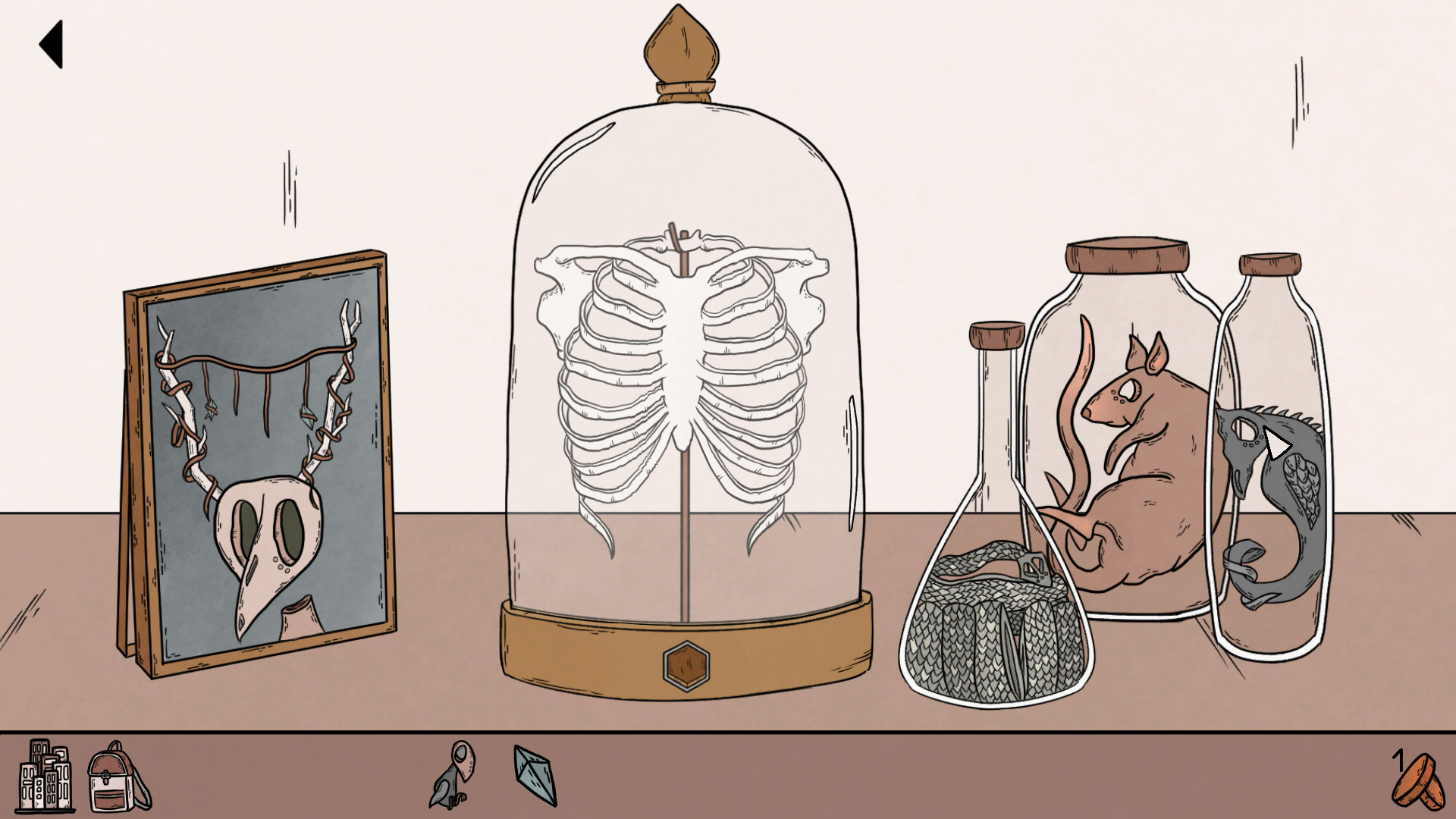

Sala's latest game, Bulwark: Falconeer Chronicles, is a city builder that he says reflects his chaotic nature, where buildings sprout and grow like flowers rather than being laid out in a grid. At the same time, it's a more relaxing experience than his previous games, which were about "wanting to be free, or conflict, or whatever was bothering me at the time". It’s an example of the unfiltered relationship between author and art that can make games from solo developers so fascinating to play – and with Sala now feeling more settled, Bulwark is about "feeling safe and creative". Getting to this point of safety, though, has been a rocky road. Sala talks about what he calls "the fear": the fear of failure, the fear of not being able to support his family.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The hard-won release of The Falconeer in 2020 was undermined by his relentless perfectionism and feelings of impostor syndrome. "Every negative review hits like ten, and every positive like one," he explains. "So you're focusing on all the negatives, which caused me to work like an animal for a year after just to make it better and get the best possible version out there." Sala admits he is something of a workaholic. "My only response when things get stressful is to work harder," he laments. But he also realizes that it would be unrealistic to repeat the work marathon he undertook around the release of The Falconeer, which took an enormous toll, and which he is keen to avoid doing again. Nevertheless, the fear persists. "I have a lot of fears about not being secure, not being able to provide, but also an intense ego or drive to make something that's good. Your internal artistic critic that says 'this is crap' is always rearing its head."

Lucy Blundell

For Lucy Blundell, going solo meant leaving her first industry job, at Macclesfield-based mobile game publisher Chillingo. She'd joined as a graphic designer almost straight out of university, and found herself responsible for all graphical design, on promotional and in-game artwork alike. "Back then they were putting out one or two mobile games a week," she says. "It was really crazy. I remember that first year, I couldn’t really go on holiday, because when I did, stuff just stopped."

When EA acquired Chillingo in 2010, it brought in another artist to ease the workload – but with the mobile game market shifting in the wake of Candy Crush, Blundell faced a new problem. "At that point, EA switched focus: they wanted us to try and find another big, free-to-play kind of game," she says. "I just didn’t like mobile games at this point. I was feeling a bit icky about them." At the same time, there were few options for advancement at Chillingo, except moving into marketing for a bigger pay cheque. "I didn’t really want to do that," she says. "Money's not a huge driver for me, but being creative and learning is." She thought about applying for a job at a big game studio, but worried that her art skills weren’t at the required level. "My 3D art was OK, but it wasn’t great. My 2D art was all right, but not good enough." It was a predicament that left her feeling stuck. So she quit.

EA's buyout of Chillingo had provided Blundell with a cash and stock payout, and she used those savings as a safety net while she established herself as a solo developer under the name Kinmoku. Knowing her programming skills weren't fantastic, she decided to make visual novels, whose coding requirements would be relatively simple. By being thrifty, and taking the odd side job doing background art, proofreading and even wedding invitations, she reckoned she could stretch out her savings for a couple of years or more. But going solo had another cost. "I got really lonely at the beginning, because I'd gone from this really friendly office where all my mates were, and where I met my husband," she recalls. "It was really sad to leave that and just be on my own." Moving to Germany after her partner secured a job at Nintendo only exacerbated that loneliness.

Blundell says that, as a shy introvert, she tends to work well on her own – so she was surprised to find how much this affected her. "There are still days when I feel pretty lonely," she says, adding that social media can help with the need for human contact, along with networking events and conferences such as GDC. "You go from nothing, pretty much not talking to anyone, to talking to everyone for like a whole week. Which I do love, but I'm always exhausted by the end of it. It's not a nice [day-to-day] balance, like you get in an office." She admits that when an event is coming up, she will practice talking ahead of time to get used to it again.

Blundell's first big project as a solo dev, Love IRL, was never finished. After a year, she had coded the first half of the game (about three hours of gameplay) up to a point where the player makes a decision that could take them along one of four branches. "These routes are all pretty much as long as that beginning," she says. She realised that coding those four branches, around 12 hours in total, could take another four years. "And it was like, 'Oh my god, I can't do that'." She tried altering the scope of the project, but it felt like too much of a compromise. Instead, she put Love IRL aside, and made her debut, One Night Stand, as part of a game jam. "It was just done in like a month, and then I put it out. No fanfare, didn't contact anyone, just put it on Itch.io – and then I went on holiday. And while I was away it started getting covered by really big YouTubers." The resulting buzz meant the free version of One Night Stand ended up being downloaded around a quarter of a million times. So Blundell set about polishing and updating the game, then released a paid version on Steam for £2.99.

Just try and work on something you can get done in six months, because it's probably still gonna take two years.

Lucy Blundell

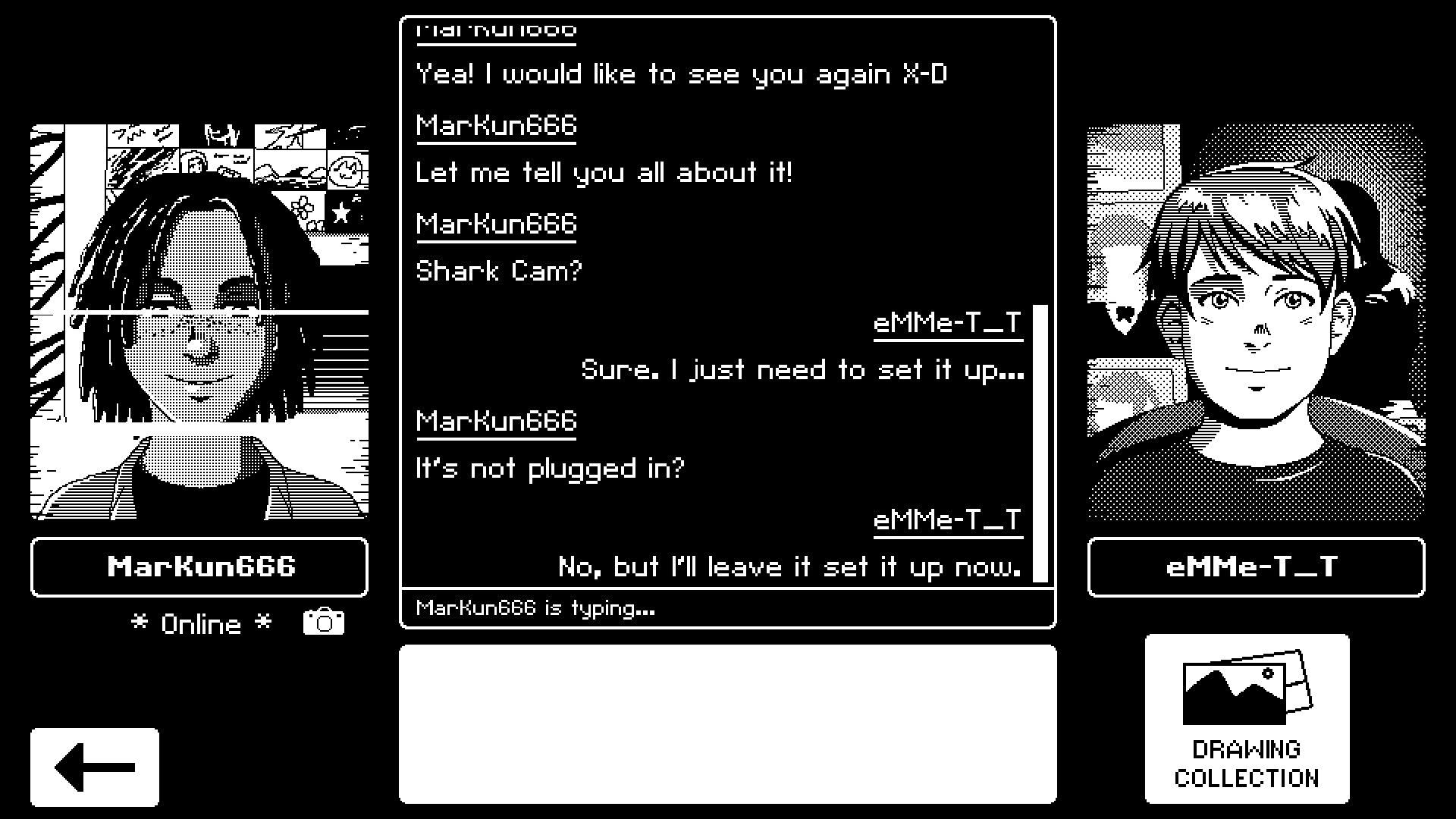

"It's crazy to think that I still get almost enough money from that now to keep doing what I'm doing." At least, as long as she lives thriftily. "I think the craziest thing I ever did was [after] One Night Stand had a really good week, when it got nominated for IGF," she says. "I was like, 'I'm buying an iPad, and buying the best one, the really big one, and I'm getting an Apple Pencil', and I just waltzed into the store and got it. Even then, it was for work." Blundell’s next project followed a similar trajectory to Love IRL. After three years of work, she realized she was never going to finish it, so it was abandoned in favour of 2023's Videoverse. She reckoned that would be a quick turnaround, taking no more than a year. It ended up taking three.

"In the last couple of years, the finances from One Night Stand were starting to go down, and I was like, 'I need to get this done quickly!'" she says. "And that’s quite scary. So I had a lot of pressure on me – it was almost like there was someone behind me the whole time, [saying] 'Work! Hurry up!'" Along the way, a lot of elements were cut – one positive, for Blundell, of working alone. "I'm only hurting myself when I do that. I'm not letting down all the artists, or the writers, or whoever's made all that stuff." But no work is ever completely wasted: some elements of Love IRL made their way into Videoverse, and Blundell files any unused art assets away in a library in case they come in handy another day. Plus, having complete control over her games means that she can decide to offset any setbacks in development by running a sale on old games or taking on side work to bring in extra cash.

Given her experiences, it's no surprise to hear Blundell's one piece of advice for anyone who is thinking of going down the solo development route themselves: always keep the project small. "Just try and work on something you can get done in six months," she says, "because it’s probably still gonna take two years."

Madison Karrh

If you loved Birth, there are a host of upcoming indie games for you to check out.

Not every solo developer comes from inside the game industry. Before making 2023's Birth, Madison Karrh worked at construction equipment manufacturer Caterpillar and made games for training doctors – and before that was following a different path entirely.

"For most of my life, I just wanted to teach kindergarten," she says. It was during her education degree, during a class on teaching math, that Karrh had her awakening. "I just loved it so much, and thought I wanted to be a mathematician," she says. "And then I learned how to code, and loved code even more. So that's when I switched my major to computer science."

That led her to Caterpillar, where she developed financial software, thinking that any programming job would provide fun challenges and problems. This one wouldn't. Faced with a desperately unfulfilling day job, she turned to making video games as a creative outlet. "I played games as a child," she says, "and then there was a big chunk of my life [when I] missed out on games – I just thought they weren't really for me. And then I fell back in love with them in my 20s." She put out her first project, Whimsy, in 2019. "It's not a good game," she says, citing the puzzles' difficulty and the "awful" UI. But Karrh is still fond of it – "it's like looking through a little diary of where I was at the time" – and proud of the fact she finished it. Yet, even as she ached for a creative role that would free her from the world of financial software, Karrh didn’t feel confident that the project had developed her skills enough to be hired by a videogame studio. At least, not the traditional kind.

Chicago-based Level Ex is a supplier of what Karrh calls "very gross medical simulations" for doctors. On one hand, it meant she got to use Unity in her day job and work with some smart people; on the other, she wasn't too thrilled about creating gamified versions of knee surgery, and the research that was required.

But she acknowledges that her experiences influenced her later games. "Working at Level Ex made me less squeamish about the body, and I think as a result there are a lot of gross bits in Birth, but it's presented in a much kinder way." It was only while working on that game, her third after 2021's Landlord Of The Woods, that Karrh considered making game development a full-time job. This was made possible in part by WINGS Interactive, which provides funding for women and marginalised gender developers.

If you're not working on something, nothing is getting done on your project

Madison Karrh

Karrh admits she was "very ignorant about the games industry in general," so was delighted to discover that there were bodies that would actually pay developers to finish making video games. 'I thought all your money comes when you release the game." A successful application meant enough cash to sustain her for a year, and leave her job at Level Ex. "Oh my gosh, it was so scary," she says, but reasoned that if Birth was a flop and money ran out, she could always just get another job. Still, it took a while for her to adapt to going solo. "If you're not working on something, nothing is getting done on your project," she says. "You can't take a day off and come back and think, 'I wonder what happened while I was gone?' Because nothing happened while you were gone." And although Karrh loved handling the programming and art for Birth, being a solo developer meant doing absolutely everything for herself, including the marketing – which she found much less enjoyable. She adds that music is her "weakest link", and that she relied on public domain classical songs for Birth, although she would like to work with a composer in the future.

There's also, again, the fear. Karrh says that sales of Birth were initially disappointing, with fewer than expected Steam wishlist conversions. "For the first two months after Birth's [release], I was like, 'OK, I'll have to get a job in a month or so'." It was only after several TikTokkers made videos about the game that things picked up. She says it's now selling "more than I need it to", adding that another benefit of being a solo developer is that the bar for success is much lower, since there’s only one mouth to feed. "I feel the fear a little less now," she says. "And I think it's because I've come to terms with the fact that if I need to go back and get a job, I will be fine. I also know that you can make something while you’re working full-time. Of course, this is coming from someone who is not a parent and has a very easy-going life."

Joe Richardson

That's not the case for Joe Richardson, solo developer of The Procession To Calvary, who has two children to support. But he started making games in his mid-20s, while at art school; after graduating, his aim was to "not have to do a real job". He'd started working part-time in a screen-printing studio while studying, although his role was mostly cleaning gear and fetching bacon rolls rather than printing. Finishing The Preposterous Awesomeness Of Everything, the game he'd begun at uni, took another year, alongside part-time work at the screen-printing studio and "surviving off the dregs of a student loan and living as frugally as can be done in London". He reasoned that if the game did well, he'd be able to continue as a developer. "And if it didn't, I'd have to get a real job," he says. "And then I released it, and it did very, very, very badly. It sold 15 copies on day one."

Prior to this, he'd had good reason to think the game might do well: PewDiePie, one of the world’s most popular YouTubers, had shown interest in the project, and Richardson had included his likeness in the game alongside those of Kickstarter backers. "Not knowing the industry at all, I thought, 'Well, I've made it'," Richardson says. "I'm going to release the game, he's going to tweet about it because he's in it, and I'm famous. And right up until release, he was messaging back and forth, and so I thought, here we go: hit 'Release', wait for the money to rain down on me. And then silence from PewDiePie, silence from the world."

Richardson says he never got to the bottom of why PewDiePie stopped replying, and why he never mentioned the game's release. This should have been the point where, as per the agreement with his girlfriend, Richardson left solo development behind. He sent out a few speculative applications to small game studios, but his heart wasn't in it. "Secretly I was fully focused on just making another game," he says. That was Four Last Things, a point-and-click adventure built from repurposed Renaissance art in only a year – something he finds hard to believe now, having worked on his latest game, Death Of The Reprobate, for some three and a half years.

I should make what I want, because I'm capable of making something great.

Joe Richardson

But times were desperate. For the final few months of development on Four Last Things, money was so tight that he had to ask his girlfriend to cover his rent. So what kept him going? He partly attributes his resistance to getting a 'real job' to his social awkwardness and anxiety. "But also an inflated sense of my own self-worth," he says. "I felt like I should be making my own thing, not making someone else's thing." Like Sala, he enjoys being able to do as he wants. "But there’s also got to be an assumption that what you want is somehow important: 'I should make what I want, because I'm capable of making something great'. I think that ultimately what makes an artist an artist is that they’re an arrogant prick." Yet Richardson is also incredibly self-deprecating about his work. So how does this square with his supposedly inflated sense of self-worth?

"Maybe it’s that I don't think I'm making great art, [but] I think I'm capable of making great art," he suggests. "So I think I'm also making shit. Having ridiculous expectations of what I'm capable of makes me view not only everyone else's work but also my own work as substandard." Though Four Last Things wasn't a big success, it sold enough for Richardson to justify keeping going. He was still picking up shifts at the screen-printing studio, but occasionally started saying no to work. "Then one day I realized I hadn't worked for six months, and I was like, 'Oh, wait a minute, I'm a professional video game developer now'." The game has continued to sell steadily. "I think, particularly with adventure games, the long tail is really important, because my games are 20 years out of date to start with, so it doesn't matter if you're a few years late to the party."

But what has allowed Richardson to remain a solo developer is the greater success of his next game, The Procession To Calvary. "For the two years after release, I was rich," he laughs. "But I know I'm not. If that was my actual salary, I’d be rich. But that's my income for those two years. If you factor in the previous ten years, if you think about the next ten years, it’s hard to get too excited." There's that fear again. "I don't know how successful the next game will be," he says. "I'm in a position where I know it's not going to sell zero, which is nice. But it might sell, like, not well at all." When Richardson set out as a solo developer, he thought he would be happy if he could make a living from his art. But now, with two children to support, he realizes he also needs a safety net, a sense of stability. He accepts that he might be able to gain that by signing a deal with a publisher, but he doesn't want to do that, to cede that control. So for now, at least, it's back to what he knows best. "Make a thing, then sell the thing," he laughs. "That's my plan."

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more fantastic features, you can subscribe to Edge right here or pick up a single issue today.

Lewis Packwood loves video games. He loves video games so much he has dedicated a lot of his life to writing about them, for publications like GamesRadar+, PC Gamer, Kotaku UK, Retro Gamer, Edge magazine, and others. He does have other interests too though, such as covering technology and film, and he still finds the time to copy-edit science journals and books. And host podcasts… Listen, Lewis is one busy freelance journalist!