From Call of Cthulhu to Dredge to Bloodborne, why does Lovecraft's influence on games continue to grow?

Interview | Edge magazine explores the video game influence of HP Lovecraft and the Cthulhu mythos

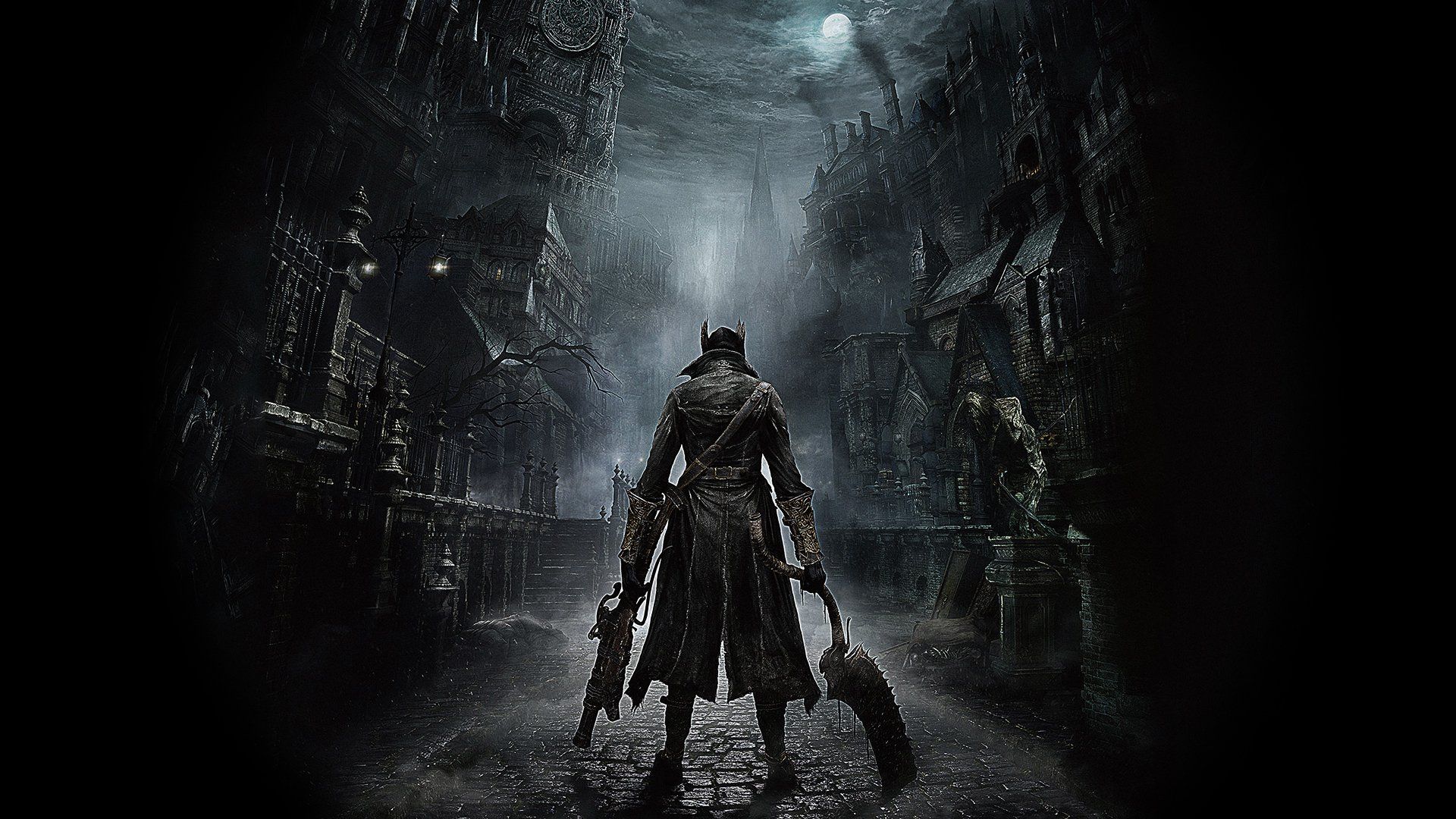

The protagonist of The Rats In The Walls uncovers a horrifying secret beneath his ancestral home, one that tracks back not only through generations of his family but entire civilisations, all the way back to the dawn of humanity. The horror of HP Lovecraft's 1924 short story isn't merely in the gruesome nature of said secret, but in the way it has always tainted the bloodline – not merely a curse but core to its existence. Similar could be said of the influence Lovecraft's writing has had on videogames. The likes of Bloodborne, Eternal Darkness and myriad spinoffs from The Call Of Cthulhu tabletop RPG are the clearest representatives here. But what about Quake? Or Alone In The Dark, or Splatterhouse before that?

In so many cases, it's hard to tell whether these works are taking inspiration directly, or whether it's something deeper in the blood. Because since Lovecraft died in 1937, barely a published book to his name, his fiction has nibbled into our cultural psyche and left paw prints over horror in all its forms. It's possible to dip a toe in these cosmic waters without ever touching any of the man's own work, filtered instead through the more contemporary perspectives of Roger Corman, John Carpenter, Stephen King, Neil Gaiman, Guillermo del Toro and innumerable others.

Yet in 2023 games with overt Lovecraftian influences do seem to be growing ever more numerous. In the space of just two months we saw the releases of Dredge, The Last Case Of Benedict Fox, Darkest Dungeon II and Amnesia: The Bunker. Very different creations, certainly, but all of them bulging with eldritch horrors. Yet we find ourselves yearning for games that dig deep into Lovecraft’s fiction – beneath the aesthetics of the ancestral home, so to speak, into the source of horror below. It's one thing to model a Lovecraftian bestiary or reproduce a shadowy inter-war New England; quite another to consider what really makes those works tick, and what it means to bring this ultraconservative writer – to put it politely – into the present day.

Culture

Of course, the Lovecraft resurgence is a phenomenon that goes beyond games, bleeding into popular culture in general. Jeffrey Weinstock, a Lovecraft scholar and professor of English at Central Michigan University, sees this as part of a general turn towards speculative fiction in recent decades, helped along by the rise of geek culture and the formation of fandom communities through social media. (Especially apt, perhaps, given that Lovecraft mainly circulated his work to fan communities through pulp weird-fiction magazines.)

Weinstock also posits that Lovecraft's fiction, in which humanity always seems unable to resist forces beyond its ken, has contemporary resonance: "I think there's a cultural relevance to the nihilistic vision he articulates, that comports with our experience now confronting various intractable problems."

At the same time, Weinstock says, speculative fiction has become a valuable channel for minority and non-western voices to express their perspectives. It's a concept that fellow academic Patricia MacCormack, professor of Continental Philosophy at Anglia Ruskin University, has considered in detail when it comes to Lovecraft's long influence.

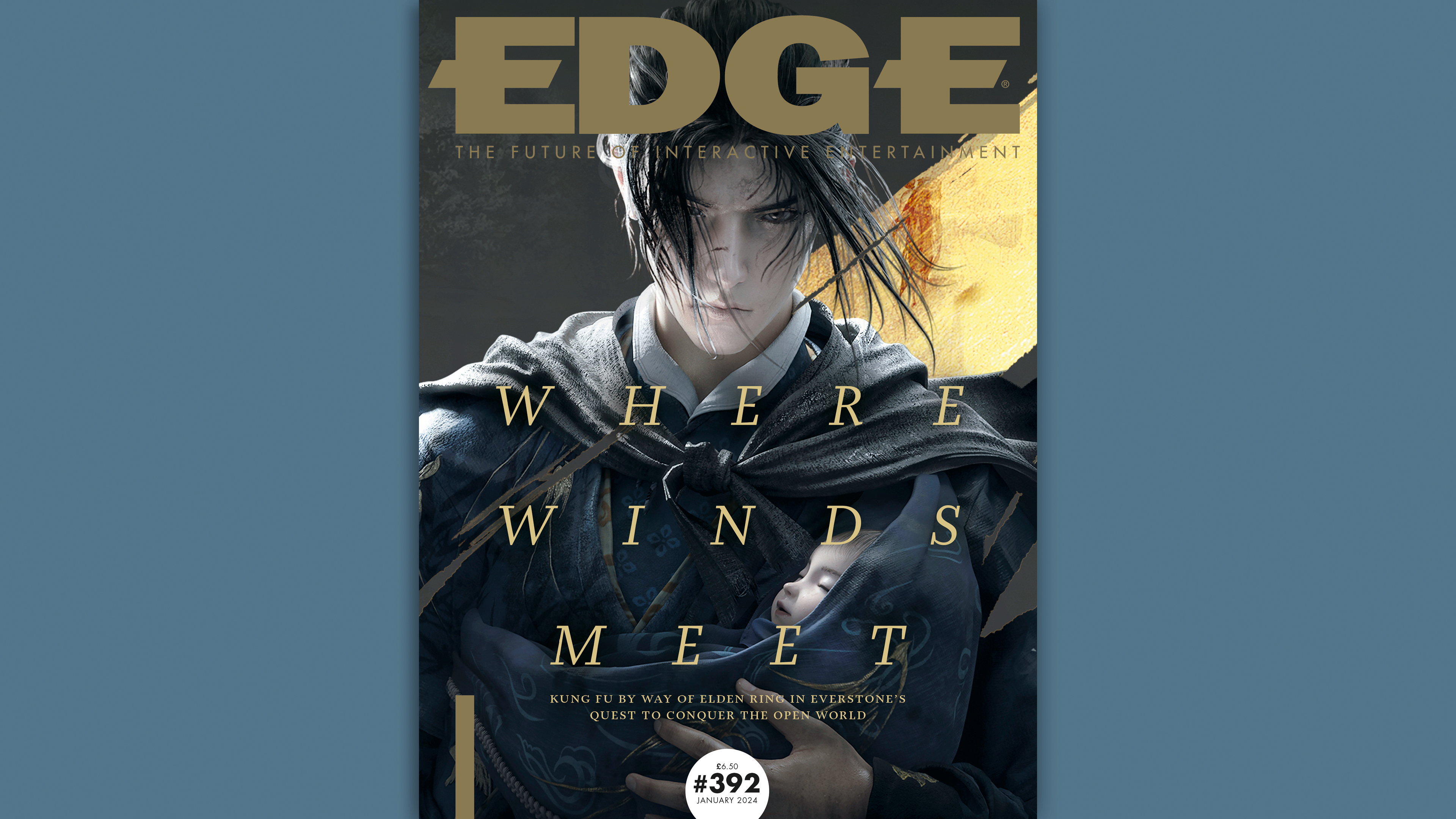

This feature originally appeared in Edge Magazine. For more in-depth features, interviews, reviews and more delivered to doorstep or digital device, subscribe to Edge magazine.

The writer's work, she argues, "has been taken up by the 'wrong' audience and produced far more interesting things" as a result. Racially critical and queer perspectives can reappropriate the weird: not as something to fear, but as something that can challenge conventional (patriarchal, colonialist) thinking, very much against the grain of Lovecraft's original intent.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

In games, though, it seems that developers are only recently beginning to understand what to do with Lovecraft's work. Among the games leading the charge here was 2016's Darkest Dungeon. Chris Bourassa, co-founder and creative director at developer Red Hook Studios (named after Lovecraft's story, The Horror At Red Hook), reckons there's obvious appeal in Lovecraft for game makers, both in terms of its monsters and the opportunity to explore philosophical themes.

With the latter, the scale of Lovecraft's horror remains compelling to Bourassa, as its characters face a reality much bigger than they’d imagined: "The best horror is these intimate encounters on small scales that burn slow and have massive implications." In creating Darkest Dungeon, he understood that a Lovecraftian tilt was ideal to subvert the power fantasies present in many games. "We knew we wanted to make a stressful, horrible kind of environment and setting. So I felt like, 'Let's go to the top-shelf quality purveyor of that type of material'."

Cosmic Horror

Another frequent visitor to the realms of cosmic horror is Frictional Games, responsible for the Amnesia series and Soma. Thomas Grip, co-founder and creative director, thinks that Lovecraft's stories themselves tend to feel like adventure games at times.

"Like in The Shadow Over Innsmouth, where the main character hands a bottle of alcohol to the local drunkard to get him to talk, it's like a puzzle." Grip is also drawn to the slow, descriptive nature of Lovecraft's work, where locations are plotted out in detail, something he has tried to carry over to Amnesia. “In Dark Descent, you're in this castle – it's very easy to grasp that setting. The Gothic feeling comes naturally," he says. "Similarly with The Bunker – you hear barrages from a distance, you hear screams, you see snipers." And these games allow players time to walk through scenes, read notes and so on, to absorb the significance of a location.

This sense of place is key to another game that metabolises Lovecraftian influences to very different ends: Paradise Killer. "What Lovecraft does well is take something that is out of our world and hard to conceive of, and then anchor it," says Kaizen Game Works co-founder Oli Clarke Smith. Thus in Paradise Killer’s island setting a dizzying, lurid fantasy of giant carved skulls and obelisks is sprinkled with 'relics' – drinks cans, key chains, coffee pots – that equally imply very mundane consumerist aspirations. And then the descriptions of nightmarish gods locate them very much in our reality.

The text for the god named Damned Harmony, for example, explains that he once dwelled in an Alabaster Citadel in Bosnia. This juxtaposition of unknowable alien gods and familiar places is something that Clarke Smith sees as crucial to the Lovecraftian experience, pointing to the author’s use of existing (if inaccessible) settings such as the Antarctic to add a touch of plausibility to the horrors described.

Yet just as vital to these works is that unknowable quality. This can present a challenge for games, which are by their nature generally heavily rules-based and visual. Grip remembers encountering this issue long ago when playing the Call Of Cthulhu tabletop RPG, which he feels overexplained the whole mythos and how it linked together. In Frictional's games, he understands that it’s a drawback to have to display monsters as tangible 3D characters.

"There has to be a T-posed model somewhere in your assets library that’s going to represent this creature," he says, "and that’s going to be a lot [less scary] than a description." Still, you rarely get a good look at that model while playing Amnesia games, unless you’re about to die, and much of the fear is conjured from unexplained sounds when the creature is offscreen. While there's always a tension between atmosphere and systems in games, Grip believes, "there are nice sweet spots where you try and cling on to [the unknown] for as long as you can."

Paradise Killer effectively deals with this problem in advance by holding its Lovecraftian concepts at a distance, with all but one of its alien gods never present in the flesh. A description such as "the goat with a thousand young," Clarke Smith says, creates "such an evocative image," precisely because it’s never depicted or expanded upon. "I don't like the wikification of fiction, where everything has to be linked to everything." The sparse text of Paradise Killer's descriptions were thus left indefinable enough that no one could draw up detailed alien biographies.

Not all games can afford to keep their monsters at arm's length, though – not least Darkest Dungeon and its sequel, both turn-based Roguelikes in which you’ll meet the same eldritch terrors over and over. The aim here was to maintain an air of mystery through mechanics, Bourassa explains. You don't get perfect information, and "characters act out in ways that are suboptimal" – for example, not taking a turn as quickly as you expect, or missing a crucial strike. "Round by round, I think that creates a little bit of dread."

But like Paradise Killer, Darkest Dungeon also relies on the power of words – in this case spoken by the narrator. "A big part of the Lovecraft charm is the language he uses," Bourassa says. "This sort of pulpy, overwrought, melodramatic stuff," for which the cultured yet gravelly voice of Wayne June was an ideal vehicle. "Modern Cthulhu stuff never hits as hard if it’s not being reflected on by a well-read English gentleman," Bourassa reckons. "There's something about the aristocracy being inconvenienced that's so endemic in the portrayal of all this horror."

Philosophy

Putting aside the practical considerations of how game developers adapt Lovecraft, there are also the thematic ones – of why. Lovecraft's stories are ripe with philosophical and social concerns, some of which take on renewed resonance in the present day. The author's 'cosmicism' views humanity as alone and weak in a universe it can't fully grasp, Weinstock says, and "increasingly, I think we confront those larger problems with things like climate change, where it's very difficult for us to wrap our minds around it and come up with strategies to respond."

This sense of constrained agency is certainly present in Darkest Dungeon’s design, and Bourassa appreciates that Lovecraft's work lends itself to such parallels. "Whether it's war or scarcity or anything existential, nobody articulated that struggle better than Lovecraft did,” he says, "[although] he didn’t really provide much of a solution." Bourassa can't be sure, though, that this means players are flocking to experiences with nihilistic leanings, especially in light of the ascent of 'cosy' games. "I think interest in bleakness, nihilism and futility is waning, because we're living a lot of it," he says, adding that Darkest Dungeon II's narrative was made a little more hopeful than the original’s for precisely this reason.

By contrast, the alien beings in Paradise Killer relate more directly to today's politics, especially the rise of rightwing populism fostered by Johnson and Trump. "They're only out for themselves, but have a legion of people believing and following them," Clarke Smith says. And, indeed, in the game.

What's interesting about Lovecraft here, he feels, is that the gods and Old Ones themselves remain beyond reach, with most stories instead focusing on small-scale manifestations of their evil. "I think that’s a good place for games to be in. It gets exhausting, saving the world all the time." But from a political perspective, too, this framing reinforces that the threat is never over, even when a particular evil is repelled. "That's similar to the modern world. The threat of fascism and right-wing populism doesn't seem like it can be defeated completely."

There is a glaring irony here, of course, since Lovecraft was far from an antifascist icon. A man of enlightenment sensibilities, including atheism, he was equally a staunch traditionalist with fiercely racist and xenophobic views. Many of his stories express unveiled disgust at foreigners and belief in the inferiority of non-white races, making it impossible to separate the work from the author, even if you wanted to. "A lot of the anxiety that's evoked in his fiction has to do with the prospect of ‘miscegenation'," Weinstock says. "Part of the weirdness is this anxiety about racial intermixing."

Grip underlines the point: "You can do good Lovecraftian [fiction] without being a racist bastard like Lovecraft, but in some ways that [racism] fuels the novels. If he had a worldview where he liked all people, he probably wouldn't have written these stories." For Grip, dealing with Lovecraft means treading carefully to avoid the regressive connotations in his work, which raises questions about how horror functions.

After all, presenting people who are different in some way as disturbing or disgusting is often at the heart of horror. Grip acknowledges that the monster in The Bunker is not only terrifying but also a disfigured person, and Soma too uses disfigurement to evoke shock and fear. "Are we promoting people being scared of disfigured people?” he asks. “I don’t think so.” But he understands it could be perceived that way. While there’s a clear difference in intent from Lovecraft overtly writing minorities as monsters, then, the potential for horror to fuel fear of an ‘evil other’ is in some ways a perennial problem inherent to the genre.

"When you go digging for gold,” Bourassa says, "you have to move through a lot of rock." He acknowledges that there's plenty of dirt in Lovecraft's work, but believes that there's enough of value to be found beneath. "The idea of people skulking around in caves and bringing up supernatural elements is scary, regardless of their country of origin," he argues.

There are themes in Lovecraft that speak more universally, he maintains, and it's possible to reimagine and repurpose them in a way that can actually sift out harmful ideas. There's also the fact that the white protagonists in Lovecraft's fiction invariably end up worse off, and in a sense their xenophobia reflects on them as part of their fear of the unknown.

As the xenophobic concerns of these Lovecraftian heroes pale into insignificance against the cosmic truths they uncover, it's possible to read them with a modern eye as pathetic figures. This was not the intent, certainly, but as an act of subversion – not only killing the author but making him spin in his grave – it can allow people with disparate views to find solace in the same stories.

"There will always be the hardcore racist chaos-magick dudes, the incel RPG players," MacCormack says. "That's nothing new." But elsewhere Lovecraft fandom has undergone a paradigm change, in which the mythos is only endlessly horrifying for the educated, white man who is used to being obeyed. "For people who have never controlled the world," she adds, "Lovecraft's cosmos has always been a teetering world of the benevolent and terrifying with nuances between."

Influence

Outside of videogames, you can find such subversions in Lovecraft Country, the TV series and novel in which the realworld racism of the mid-20th century is scarier than the monsters, and in Julia Armfield’s novel, Our Wives Under The Sea, where cosmic horror acts as mere background for an intimate study of love, loss and acceptance. Games have tentative form here, particularly in psychological horror titles such as Signalis, but also in a few more overtly Lovecraftian works. Even Soma has a few such elements, Grip explains, with the 'monstrous' disfigured presented as living people who can even be happy. "There's no one telling you how to feel about that," he says. "You are the final judge on what you think about these things."

It's Paradise Killer, though, that has arguably done the most to turn Lovecraft on his head. Its gods may be terrifying but they're also "bizarre, capricious idiots," Clarke Smith says, and the ruling Syndicate that worships them and has been granted immortality feels equally ridiculous. Rather than some clandestine foreign cult worshipping the alien deities, here it's an elite clinging to power in the most obscene and stupid way – enslaving and sacrificing citizens to aliens who would happily destroy them.

Yet at the same time, racial and gender hierarchies aren’t apparent within the game's diverse cast, as such mortal concerns evaporate within the Syndicate, and the rest of humanity had already come together in the past to drive back the gods. A big theme in the game is unity, Clarke Smith says: "Groups of people coming together to make the world a better place." Although of course, he adds, the Syndicate is massively misguided in its notion of what that entails.

While Lovecraft would no doubt baulk at some of the ways game developers – and creators in many other artforms – are making use of his mythos, he would also surely marvel at the sheer number still under his influence. And this, at least, is in line with some of the man’s more palatable views.

In his lifetime, Lovecraft encouraged others to participate in his creation with fan fiction, and collaborated with fledgling writers to expand the universe. It's a natural response to the irresistible pull of this bloodline, then, to reimagine and recreate his legacy. For developers approaching this font of cosmic horror, nothing should be deemed too weird to try. As Weinstock concludes: "It's an early kind of open-source world. The Lovecraftian mythos is something much bigger than Lovecraft himself."

This feature originally appeared in issue 389 of Edge Magazine. For more in-depth interviews, features, and more, subscribe to Edge.

Jon Bailes is a freelance games critic, author and social theorist. After completing a PhD in European Studies, he first wrote about games in his book Ideology and the Virtual City, and has since gone on to write features, reviews, and analysis for Edge, Washington Post, Wired, The Guardian, and many other publications. His gaming tastes were forged by old arcade games such as R-Type and classic JRPGs like Phantasy Star. These days he’s especially interested in games that tell stories in interesting ways, from Dark Souls to Celeste, or anything that offers something a little different.