From Call to Duty to Dead Space, Bond to Barbie: A career retrospective with Glen Schofield

"Those were the Wild West days of making video games, man"

Glen Schofield was confident when he applied for his first job in the game industry some 30 years ago. "I can do this," he remembers telling himself. "Little did I know how hard it was!" Either way, he could hardly have imagined that, three decades later, he’d have worked with some of the world’s biggest brands: from Barbie to Bond, Disney to Call Of Duty.

Having gained a degree in commercial art from Brooklyn’s prestigious Pratt Institute, he started his career as an illustrator in New York before moving to a multimedia company where he learned about computer graphics, using tools such as DPaint. When he was given a commission to illustrate covers for Game Boy games, his career path was set.

Making games was, of course, very different back then: at the time, he says, he could be involved in as many as eight releases per year. In his role as art director at Absolute Entertainment, most games were made by just two people: an artist and a programmer. "In most cases, the artist was the designer; the engineer mostly spent time implementing the game, and they would also do the music at that time. They had their hands pretty busy. So I ended up designing all the time."

This feature first appeared in Edge magazine. For more like it, subscribe to Edge and get the magazine delivered straight to your door or pick it up for a digital device.

A move to California to become art director at Capcom America in 1994 proved transformative, even though he only worked on one game there, contributing art to Street Fighter: The Movie. "I was the third guy hired there. They hired the president, the vice president, and then me, the art director. And guess who had to do all the work! I was painting the walls, buying equipment, and all sorts of things. But it taught me a lot about setting up a studio, which I used in my later years."

After joining Crystal Dynamics, Schofield led his first project, directing Gex 3D: Enter The Gecko, where he worked with Evan Wells and Bruce Straley, latterly of Naughty Dog fame. Schofield directed six games there, running the studio for a while before another move to EA, where he assumed production roles on several big-name licences, from James Bond to Lord Of The Rings.

But it was with a new idea that Schofield made arguably the defining game of his career: 2008 chiller Dead Space. "My elevator pitch was: I want to make Resident Evil in space," he grins. With its brilliant diegetic interface and grisly 'strategic dismemberment', it earned Schofield some of the best reviews he'd ever had.

Following a stint at Sledgehammer developing three Call Of Duty games, it's no surprise that he's returning to science-fiction horror with The Callisto Protocol. And despite the demands of his role as a studio head, he's still unable to resist getting involved in art and design – hopefully without becoming too much of a backseat art director. "I don’t want to be too prescriptive, because I've got some great people on the team. I won’t tell them exactly what to do if I don't like something. But I'll tell them if it's a little off." As an artist, Schofield has always recognised the importance of fine details; as he reflects on his career to date, it's clear that's what got him where he is today.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

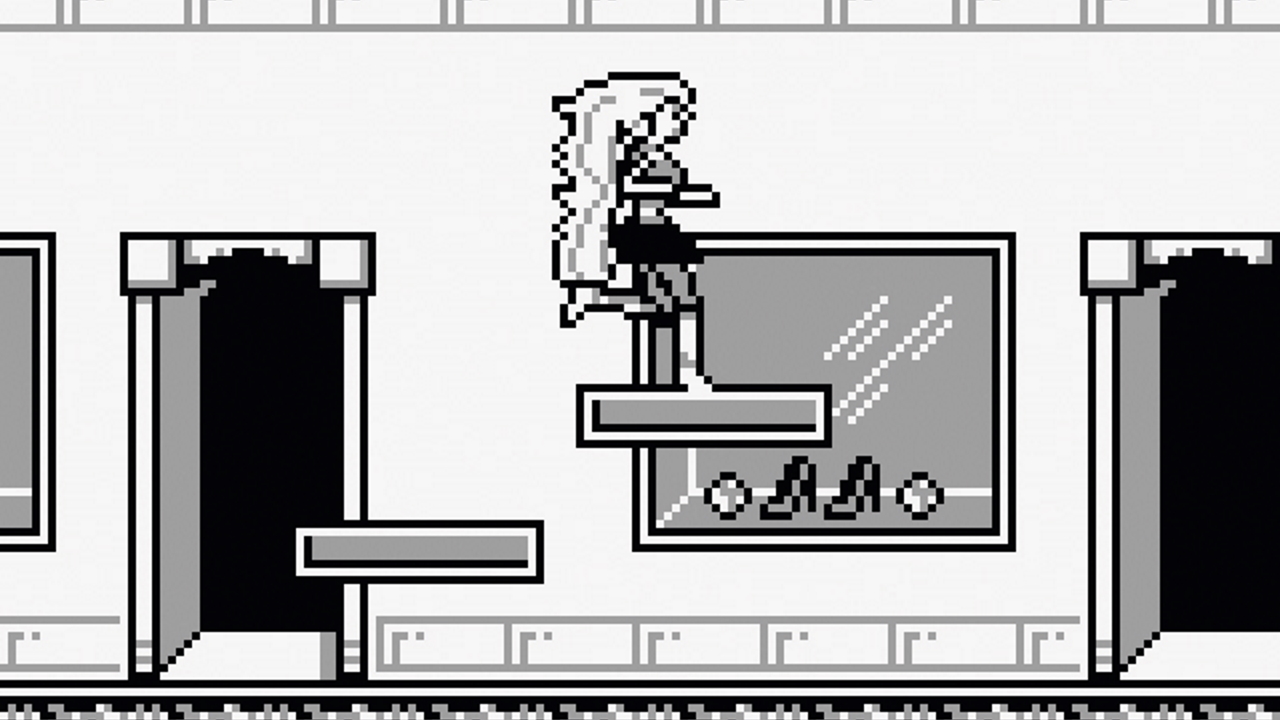

Barbie: Game Girl (1992)

"There was a small company in New Jersey, I think I was like the 12th or 13th person hired at a place called Absolute Entertainment. We did a lot of the work for Acclaim – they were a powerhouse in the ’90s. So I did a lot of cartoon games, things like Swamp Thing, Bart Simpson, Ren & Stimpy, and Rocky And Bullwinkle and a lot of the other big cartoons that were around at the time. I worked on a Goofy game where I learned a lot because the quality standard for working on a Disney product is just really high. I had to train a little bit with a couple of Disney artists and get the style down. We were kind of creating a newer style for them – it wasn’t pure 2D; they wanted some shadowing and things like that in it. Man, did I learn a lot on that product!

I moved up to art director, as a bunch of my games were pretty successful. Believe it or not, my first game was called Barbie: Game Girl. They thought it would be funny if the new guy did the Barbie game, but little did they know that Barbie would outsell everything that we did that year [laughs]. I don’t take any credit for that – I give that to Barbie, the licence. But I did my studying on it.

I mean, I didn’t know anything about Barbie, so I had to go out and buy some Barbie dolls, and I had to look at the clothing. I went into women’s clothing stores so that I could understand it a little bit more. So I did my research, which was a little embarrassing at times… and the guys would put a Barbie doll on my chair in the morning, and a purse, or things like that. They wanted to have a little fun with me, but I got the last laugh in the end because I became the art director."

Gex 3D: Enter The Gecko (1998)

"I got a call one day from Crystal Dynamics to come up for an interview and I remember going up with all my drawings. Because as an art director back then, you did all the drawings and backgrounds and characters – and I had a ton of them. I went in with big pieces of paper and canvases and all sorts of things, and they hired me on the spot, as the producer. They wanted me to produce Gex, and within a couple of weeks of being there they put me in charge of the game. The guy who was in charge – who was a lawyer, believe it or not – he said, 'I don’t know anything about this – you take over from here', and he went on to run the studio and I went on to run the game.

So Gex was my first 3D game. I went there and I saw that they had this beautiful engine and no art. And I’m like, ‘My god, this is perfect for me’. Because I knew how to create art and how to hire artists and get the game going. And they did have a game designer there, but I worked with the game designer to help design the game.

"Those were the Wild West days of making video games, man"

Those were the Wild West days of making video games, man – you could do almost anything, and Gex was about as irreverent as you could get at the time. Gex was crazy because he could walk on walls and ceilings, so that made it tougher but easier [to design] in some ways, because he could do all sorts of things, but you didn’t want him just going everywhere. You couldn’t do that at that time, either, because you were messing with the camera all the time.

I ended up directing six games while I was at Crystal Dynamics, and I ended up running the studio for… I don’t know, a year and a half, maybe two years? I was part of the team that picked Eidos to buy us. There were about six or eight of us in the room and we voted on which company we wanted to buy us and we picked – unanimously – Eidos. Because at the time, Tomb Raider was a powerhouse, man. It was the thing, you know. And we just wanted to learn from those guys if we could."

The Lord Of The Rings: The Return Of The King (2003)

"I directed a Knockout Kings game [for EA]; then they asked me to come over and help on Return Of The King. For the first year, the executive producer of the game was finishing Two Towers, so I was the EP running Return Of The King, just getting people on board, getting the engine up and running, starting to do the design and work on what the screenplay would be – because you had to adapt this giant book and movie into a videogame. And then when Neil Young finished working on Two Towers, he came over and ran the game, and I was producer – I was producing the levels.

So I had a huge job of designing and producing and getting the levels done – I was like the number two guy behind Neil – and getting that game out the door. And I’ve never worked so hard. I mean, we were working seven days a week, because it had to come out before the movie, and we had less than a year to make it. This was the first time we had a team of about 175 people – a giant, giant team. So I guess I was [in charge of] at least 100 people because most of the emphasis was on the levels. Oh my gosh, it took a lot of work."

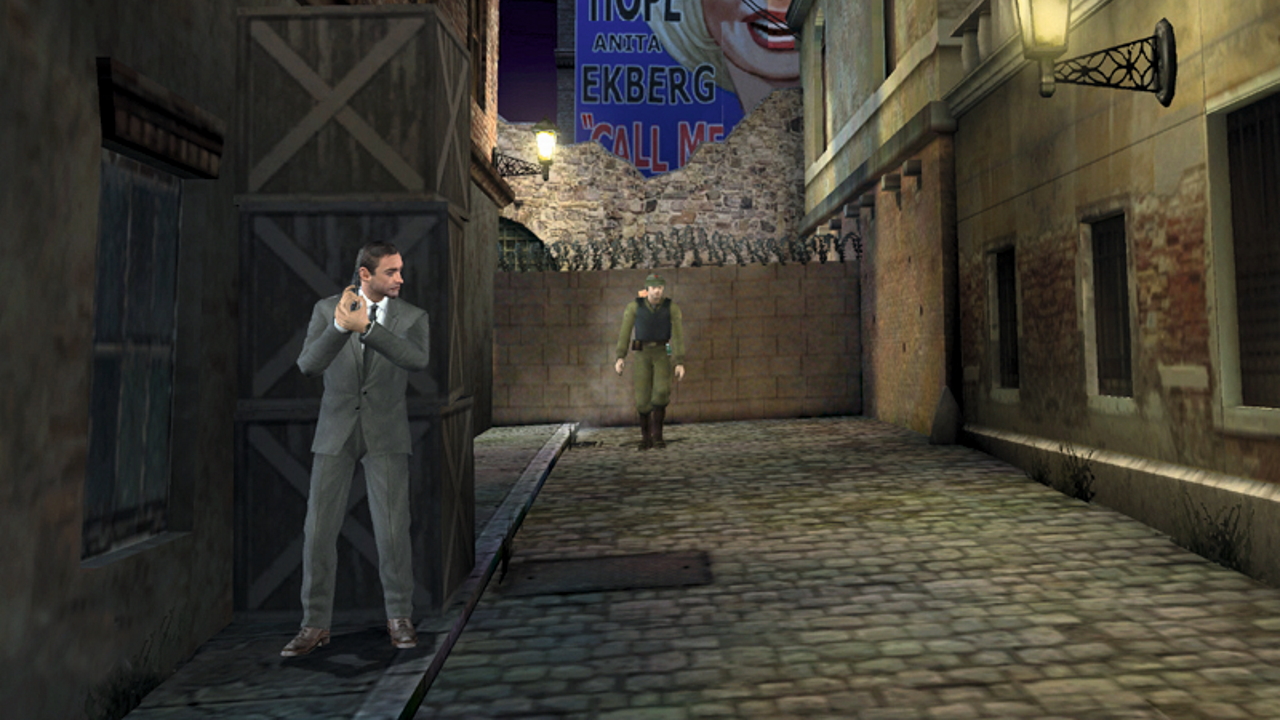

James Bond 007: From Russia With Love (2005)

"What was great [about Return Of The King] was that it was where I made a good rapport with many of the artists and designers and guys who worked on the levels. After that, they put me in charge of Bond, which was a big feather in my cap. I was very proud to get the James Bond licence. But all these people, I started to get to know these guys really well, and we went on eventually to make Dead Space. But, yeah, there were a lot of licensed games. I look at the early 2000s as the heyday for licensed games. I mean, everything was in the studio: Harry Potter, Tiger Woods, just one right after the other. The Godfather! I even worked on The Godfather for a while there.

After those three games, I got an offer to go to Activision. Because what happened was, they asked me to make another James Bond game in less than a year, and I was like, "This thing is going to fail." Because there’s no way you can make a game in less than a year. But they had a contractual agreement with the Broccolis and whoever [owns] James Bond to get it done in another year. And so I was looking at about a ten-month production. I had just made one in 12 months, and got like a 78 [Metacritic] or something like that on it, and I knew that this one was bound to fail."

Dead Space (2008)

"I kept saying about this Bond game, 'I can’t make it. I can’t do this.' And they were like, 'Yes, you can.' So I went out and I got an offer from Activision. I gave my two weeks notice at EA and they tried desperately to get me back. Which I appreciated a lot – I didn’t realise that I had been appreciated that much. And finally, the president [of EA Worldwide Studios] Paul Lee asked me what it would take to get me to stay. I said, 'I want to make my own game. But in order to make my own game, I need a team of 15 to 20 people at the beginning, and you’ve got to leave us alone for six months.'

Because EA was notorious for… if one game needed help, they would just go to another game and grab a bunch of people and bring them over. And that’s what led to some games coming out late and some games coming out and getting lower scores, things like that. So I just wanted to be left alone, and they kind of put me in a corner for a while.

We had this small team, and we made a little demo of this scary corridor. We were like, 'We’re just going to cut off limbs – we’re just going to be about dismemberment'. And everybody was like, 'That’s going to be too gross. It’s going to be too much for the public', and things like that. But we made this great-looking demo.

The other thing I did, I worked on with my art director at the time. Because when you were at EA, and especially back then, you were competing against like, 40 games worldwide for money. You know, they had Tiburon, they had Montreal, they had Vancouver, and Redwood Shores, which was making probably six or seven games of its own. So you were competing against all these games, and they would only make so many a year.

So we made posters, and we hung them up all over EA. I would hang them up in the bathrooms. I remember we even made a calendar for Dead Space with this very early art. We were trying to sell it within EA, and it worked. But what really worked the best was the demo: EA saw that they had something special and they put more and more people behind it. And they gave me what I needed.

"You never know when you make any game what you’ve really got before it comes out"

"It took a while for them to understand it because this was something that they hadn’t done before. ‘OK, we’ve got a brand-new IP, it’s science fiction, it’s horror – how do we sell it?’ That sort of thing. But eventually they greenlit the project, and they got 100 per cent behind it. After that, [John] Riccitiello finally came in as as the new CEO, and he loved it. He was a big advocate for the game. I think they still wondered how they were going to sell it because they were used to licensed games, but they gave us us some money and we were able to finally get the game off the ground.

"I remember showing it to [Shinji] Mikami. EA was always having people come in from different game studios. At the end of it, he bowed. We showed him one level, and he bowed to me and he said, through an interpreter, 'You’ve got something special.' And I was so proud. I was like, 'Wow, maybe we’ve got something great here – I don’t know.' You never know. You never know when you make any game what you’ve really got before it comes out.

"I’ll be honest with you, I still didn’t know what we had once we shipped the game. I was in Europe when the game came out. I was on a PR tour. I remember being in a hotel lobby and I started getting calls first thing in the morning, which was late the night before from the US. I was getting these emails and calls: 'Are you seeing the scores?' I’m like, 'No, no.' And I started looking at the scores, and I was like, 'Oh my gosh.' I was stunned.

"When we were making Dead Space, we didn’t think of sales, we didn’t think of scores, we didn’t think of awards – we were just focused on quality and making something we were passionate about. I know that sounds weird – like, yeah, you should do that. But back then you were focused on getting the game out on time, what your sales were going to be, things like that.

In this case, it was the opposite – I’d just worked on a bunch of licensed games and I wanted to focus on quality, so that’s what we did. All of a sudden it started getting these great scores and we were stunned, and then we started winning awards. The initial sales were OK – if you look back, I think it took a while for the sales to get off the ground, and of course a sequel always helps. But it turned out to be something I’m really proud of. When people come up to me, of all the games I’ve made, that’s the one they like to talk about the most."

Call Of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 (2011)

"It was so hard to leave Dead Space. But I thought it was time to make my own studio. So I talked to Michael [Condry], who had been my development director on a number of games, including Dead Space, and I said, 'Maybe we can go out on our own. I know a couple of people over at Activision – we could talk to them.' It took a long time for it to develop. But Activision finally signed off on it and let us build a studio – a Call Of Duty studio.

We first started making a thirdperson Call Of Duty game, an action-adventure game, completely different. And then things went a little south with Infinity Ward and I remember one day a bunch of execs flew up and said, 'How would you like to work on Modern Warfare 3?' [Laughs] It didn’t take long to just say, 'Thank you, yes, we’ll work on that.'

We went on to make the singleplayer game and Infinity Ward made the multiplayer aspect of it. I have to say, I learned a lot from the guys that were still there at Infinity Ward. They had made some awesome games – Modern Warfare 1 and 2 started the franchise and so even after a lot of people had left there still were some really great people there, and I learned a lot from them on how to make a Call Of Duty game. But what was nice is that game also won Action Game Of The Year, just as Dead Space did, so it was like two in a row, which I was really proud of.

"We first started making a thirdperson Call Of Duty game, an action-adventure game, completely different"

I actually think we went into it a little naïve. We’d just made Dead Space – we’d just made a good game and so we [thought], ‘Ah, we can make this game.’ Again, I thank Activision and Infinity Ward for helping teach us. There was a lot of pressure because we also had to get it out on time, which was at that point I think about two years out. And we also knew we were following up one of the best games of all time – you know, not just the best shooter, but one of the greatest games ever.

But Call Of Duty also allows you to hire some really good people. People want to come on board. So we built a really good team at Sledgehammer – really good vets, and then people out of college – and we were able to get some of the best of the best to come work on it. But, yeah, I think we went in a little naïve, and when it was all done I could turn around and go, 'My god, I became a better game-maker because of this game.'"

Call Of Duty: World War II (2017)

"People nowadays [think] a Call Of Duty is… you know, just put it through the grinder and another one will come out. They don’t realise how much work goes into making a Call Of Duty game. There’s just a ton of research. You’re working with experts – I studied World War Two for three years. I worked with historians. I spent eight days in a van in Europe going to all the places that were going to be in the game. I shot different old weapons. All these things that you have to do when you’re working on a Call Of Duty game. And, you know, to become an expert – Advanced Warfare, we worked with Navy SEALS and Delta Force people to learn and tactics and techniques and get them into the game, right? You had to learn about the Special Forces from different countries like England and France and Spain and Italy and all that, because they were all in the game. So, a lot of learning, constantly reading, constantly watching videos and constantly working with experts.

Was there internal competition? No doubt, no doubt. It’s weird, because you really rooted for each studio because you needed and wanted every Call Of Duty to do well. But you always wanted to get a higher score. You wanted to achieve more sales if you could. So yeah, we pushed each other, we really did. But then again, we would also help each other out – like, in between, we would go help out Black Ops a little bit. We might take on a level or take on a few objects and things like that – vehicles and things. We were this sort of Call Of Duty brotherhood. There was a quiet competition definitely going on, but you helped advance the next game as much as you possibly could.

"There was a quiet competition definitely going on, but you helped advance the next game as much as you possibly could"

WWII was very difficult subject matter. We actually lost people from the studio who just didn’t want to go there because it was a difficult time. But we approached it knowing that it was difficult time in history. We had to find a storyline that had a long throughline, where you could follow one group, so that was the main thing that I was concerned with. I studied the Italian campaigns and the African campaigns and the European campaigns, and the one that had the longest throughline was following the Big Red One – the advance of landing on Normandy and then just going all the way through France and Belgium, all the way up into Germany. So we knew that we could do a story there.

You’ve got a lot of nationalities that you have to pay homage to, and at the same time you’ve got to be careful about the Germans as well. We spent a lot of time in Germany, making that game, talking with locals and people about how they felt about it. And so we went about it with that [in mind]… you know, there’s a section in there where you rescue a German group, things like that. So we wanted to have that sensitivity. And then we also knew [there would be] controversy, like when the Jewish soldier is taken and beaten and put into a special prison. A lot of people didn’t know it at the time, but the [Berga] concentration camp was one that was just for Americans. It didn’t have a lot of people in it, but it had a few hundred Americans there. And, like anybody else in a concentration camp, they went through hell."

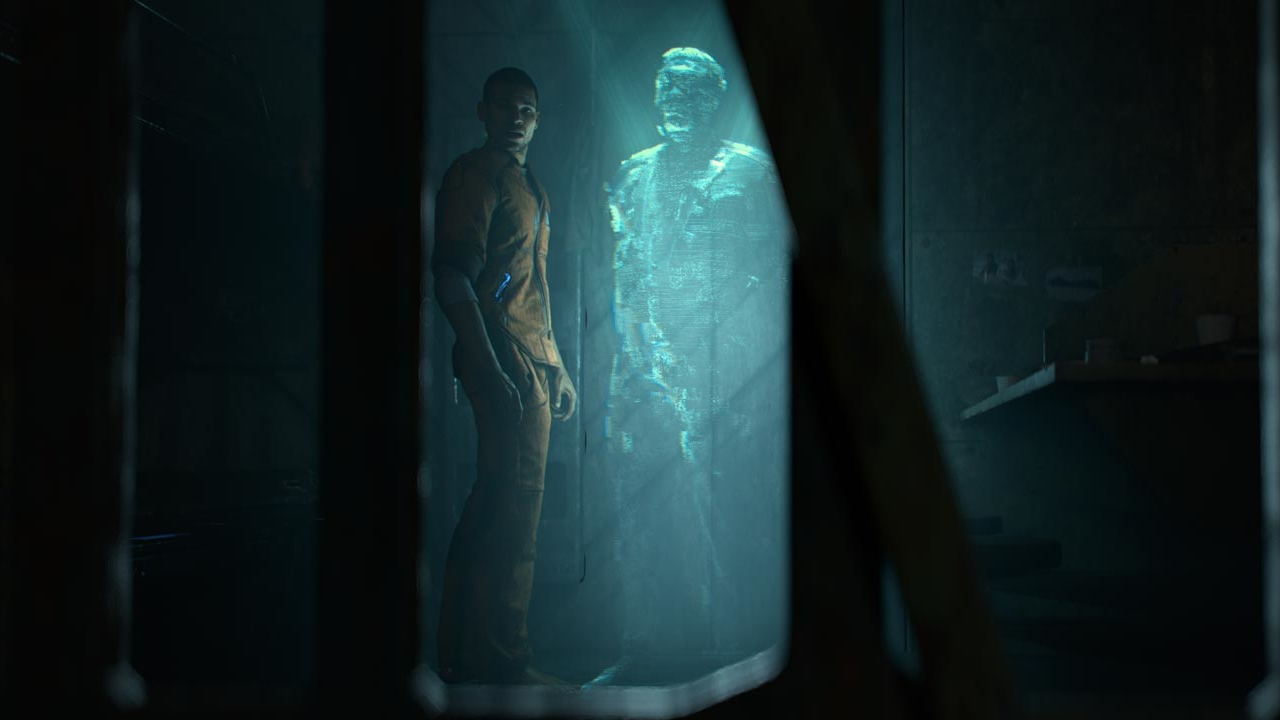

The Callisto Protocol (2022)

"I stayed at Activision for about a year after WWII. I was working on some special projects and helping out on a few things there, trying to figure out what I wanted to do next because I didn’t want to make another Call Of Duty game. I eventually [decided] I wanted to form another studio, and that I’d like it to be closer to home. And I’d like to make another one of my own IPs – stuff I couldn’t actually do at Activision any more.

So I took some time off and wrote out a bunch of ideas. And I was writing out… I guess you would call it a screenplay, maybe 20 to 30 pages of stories here and there. I wrote a few of those. At one point, I went out to the desert down in Tucson, and spent some time at a resort for a couple of weeks, and would just go out and come up with ideas. That was a great way for me to think – I would go out there with my drawing pad and just come up with ideas and then write them down.

"I looked at just about everybody, but I kept coming back to the PUBG folks"

Eventually, I just came back to [thinking] I want to do another sci-fi horror game and go back to my roots. Like, what I really love the most about Advanced Warfare is that it’s got science fiction in it. If you look at WWII Zombies, which I directed as well, that’s a real horror game. It wasn’t the typical Treyarch one, it was more Visceral, if you will. So I wanted to go back to those things that I liked a lot, and wrote out this story. And then I just went about looking for, you know, somebody who would want to make the game, which is a big undertaking.

I looked at just about everybody, but I kept coming back to the PUBG folks. They just had this attitude about them that was creativity first, and everything else follows. And they were like, 'We don’t want to get involved in your game. We want you to make the game that you want to make.' It was really refreshing to hear it. There are times when you’re like, ‘Do I actually believe them?’

But now that I’ve been here almost two years… I had a meeting with them last night and they loved what we were doing. They gave us a little bit of feedback, but more like testers, if you will. We just get guidance. They’ve been really great to work with. I decided to go with them, and it’s been the right decision."

For more fantastic previews, reviews, and in-depth features, you can pick up the latest issue of Edge magazine from Magazinesdirect today.

Chris is Edge's deputy editor, having previously spent a decade as a freelance critic. With more than 15 years' experience in print and online journalism, he has contributed features, interviews, reviews and more to the likes of PC Gamer, GamesRadar and The Guardian. He is Total Film’s resident game critic, and has a keen interest in cinema. Three (relatively) recent favourites: Hyper Light Drifter, Tetris Effect, Return Of The Obra Dinn.