From Journey to The Unfinished Swan: Looking back on a decade of emotional experiences

From Journey to The Unfinished Swan and Dear Esther: How simulated strolls broke the mold a decade ago

Daring to be different is often met with suspicion - something that's as true in video games as it is any other part of life. Unfamiliar concepts may be turned away by overzealous gatekeepers, or interrogated in the belief they hide unseemly motives. That was never more true than ten years ago, when the indie boom brought a wave of games that seemed to reject established rules of the genre and interactivity in favour of more contemplative experiences.

Some were derided as 'walking simulators,' or accused of failing to meet arbitrary standards of what constitutes a game. But like them or not, these titles capsized old debates about games' ability to tell stories or evoke emotional responses - and the pivotal year in this shift was 2012, when a trio of developers decided to stop and smell the roses. And, detractors aside, it turned out plenty of players were equally ready to sniff.

The path less travelled

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more in-depth features interviews delivered to your door or device, subscribe to Edge in print or digital.

One fresh-faced company that strolled into the fray that year was Giant Sparrow, with its flagship title The Unfinished Swan, a game where the most taxing interaction is applying paint to your otherwise-invisible surroundings. "There was a significant segment of players who were angry that this game existed," creative director Ian Dallas tells us. This pushback was a result of zero-sum thinking, he reckons - "If there were games that were not about challenge, that was an existential threat to games they loved" - and of expectation.

This audience thought they were getting a puzzle game, perhaps something like Portal, but The Unfinished Swan was never supposed to be anything of the sort. "When they played it, they were like, 'This is a shitty puzzle game," Dallas says. "You're right, it is a shitty puzzle game. Moving forward, I've tried to be clearer about what to expect, but that's hard when we're making a game where the whole idea is you have no idea what to expect."

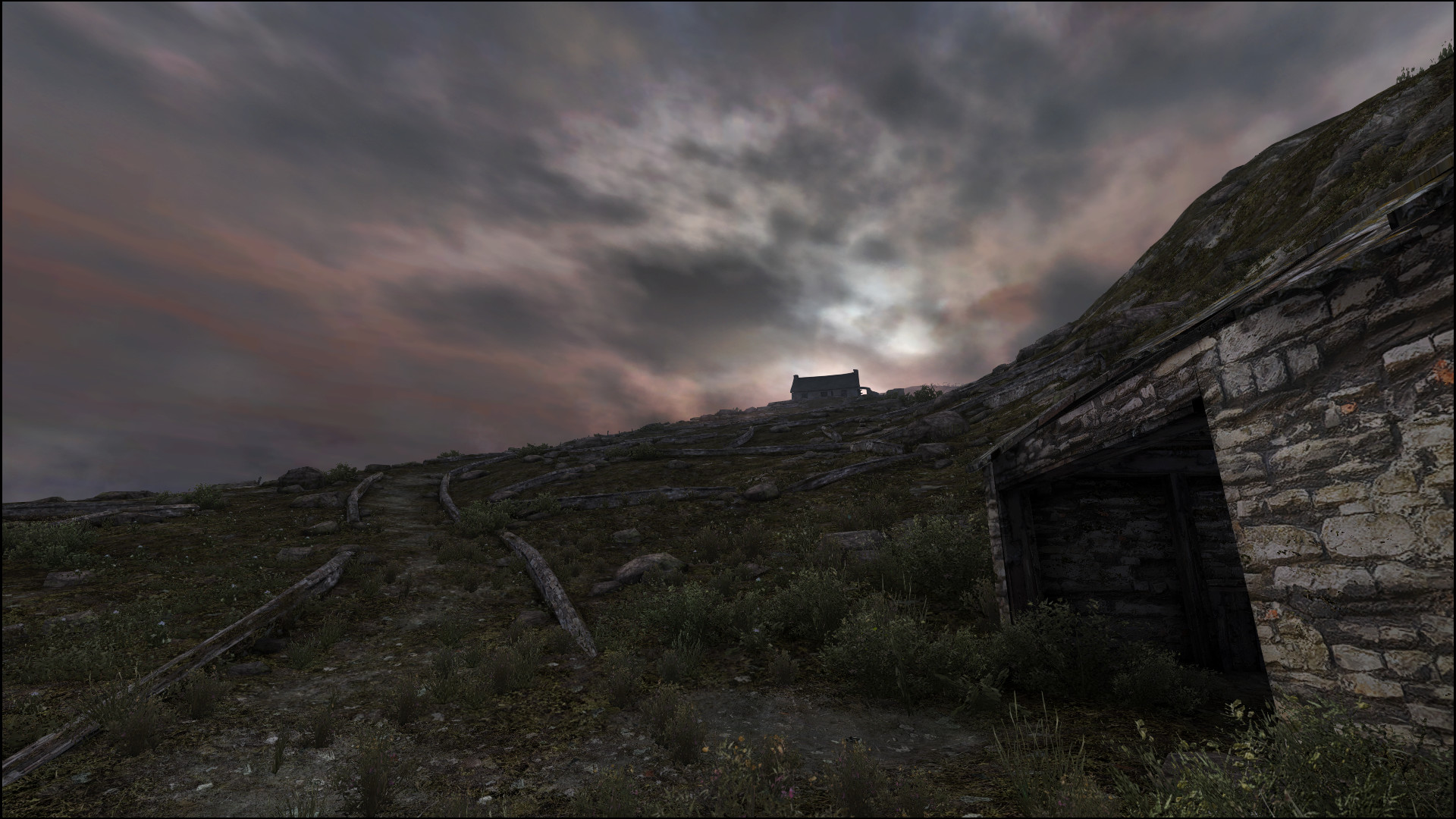

Dan Pinchbeck met similar resistance that same year, his studio The Chinese Room released Dear Esther as a commercial product. No surprise, perhaps - here was a game that truly embodied the moniker, as you wandered an Outer Herbridean island heading towards your narrated fate. As Pinchbeck sees it, the reaction to its release was an early example of the now exhaustingly familiar patterns of online outrage. As such, he doesn't see any point in engaging with it.

"Some of the stuff thrown at us was so extreme that there was no dialogue to be had," he says. Nor did he find arguments convincing. "Because [Dear Esther] came from a real love of first-person games; I wasn't having anything to do with this 'You hate games, you're destroying games' thing." Besides, Pinchbeck is old enough to recall how experimental games have been back in the 1980's, on home computers. "[They were] absolutely barking mad," he says, "so I'd always considered games to be a medium that constantly pushed its own boundaries."

The Journey

If there’s any question of whether Journey fits the (somewhat dubious) definition of a walking simulator, being a third-person game where your feet frequently leave the ground, the backlash it faced in 2012 put it firmly in the company of these other games. But this wasn't developer Jenova Chen's first rodeo. Since co-founding Thatgamecompany years earlier, Chen had established himself as a purveyor of emotional experiences.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"When we made Flower in 2009, people were like, 'This is not even a game. There's nothing to kill'," he says. The problem, as Chen sees it, was that the player base and industry were too narrow and insular. When he first came to the US in the early 2000s, "most console games were considered 'mainstream', but that mainstream was basically a bunch of young men, and mainstream [should be] everyone, right?" Chen thus made a conscious effort to entice new audiences and broaden horizons. "We wanted to show the world that games are not just guns and competition, that they can be a positive influence," he says. "I’m so thankful when people who have never played games [before] consider playing games, a medium we love. So we have to make sure our games are accessible."

As for the origins of these games, it's surely no coincidence that Dallas, Pinchbeck and Chen all studied games at postgraduate level - and all of their 2012 releases were born in academia, or else evolved from projects they'd started there. "Before our generation, the only way to learn how to make games was to join the industry, or do it at home," Chen says. He began studying interactive media at USC's School Of Cinematic Arts, in only the second year the department existed. "We were taught about making games as if it was academic research." This meant not only considering the history of the medium, but also its limits.

"You didn't go there to learn the basic skills so you can get hired," Chen says. "You went there to become an expert." And with that came a pressure to be a pioneer. "Our professor would say, 'You've wasted $90,000 to come here and three years of your life - you'd better do something really meaningful after grad school'." It was here that the journey towards Journey began, with a grant-winning student project.

After being asked to produce something different to the mainstream - which at the time for Chen meant Grand Theft Auto - he developed a concept for a game about clouds, a healing and relaxing experience. Even then, he still struggled to extricate himself from conventional game-think when asked to define the game's mechanics. "I thought about SimCity and how you can create disasters with storms." Chen says. "My instinct was based on the games I played - and all I could think about was destruction."

It was his professor, Tracy Fullerton, who suggested the protagonist might be a young boy, and Chen started to think more about emotions and life experiences. "Kind of subconsciously, as I started working on this game, I put more and more of my memories and feelings of childhood into the project." The result was a game about a boy who's ill in bed and dreams of flying, forming the clouds into different shapes and using them to wash away pollution.

Time Bandits

The Unfinished Swan, meanwhile, began life as a VR prototype focused on throwing multicoloured paint around a room. Dallas then added "the most stock, cringey story" to expand the concept, introducing invisible environmental features that the paint would reveal. "It was awful," Dallas says, but he submitted it to festivals anyway. When the prototype grabbed Sony's attention, he had to figure out how to turn it into a full game. "The experience I wanted to extend was the sense of not knowing, keeping people feeling like they were at the start of the game, before they move on to the mastery part."

Dallas doesn't recall other games at the time that he could draw on. "I wish there were." He points instead to Alice In Wonderland and films such as Time Bandits and Labyrinth as influential sources. "It’s sort of embarrassing, but every game I make is Time Bandits," he says. "It’s the seminal reference I just can't get away from." Following this course, he never really considered more conventional mechanical challenges. "It didn’t feel like the game to force people to have to prove they understood these things," he says. "It was about surprises and delight."

As for Dear Esther, the initial inspiration for this atmospheric ramble through desolate surroundings was – what else? – Doom. During his PhD, Pinchbeck began experimenting with mods for Id’s influential shooter, and things evolved from there. "In most first-person shooters, the basic idea is you make the environment simpler by removing things with extreme prejudice," he says. "So what happens if we flip it on its head, so the environment gets more complicated as it goes? It was little things like that, little research questions.”

With Dear Esther the particular question was whether the quiet moments in games such as Doom and System Shock, between bouts of violence, could be extended into a complete experience. "A lot of the time, nobody’s doing something because it doesn’t work," Pinchbeck says. "But there's always the chance that something hasn't really been explored just because it hasn’t really been explored." It would turn out, of course, to be very much the latter.

Emotional connection

Dear Esther had initially been released as a Half Life 2 mod in 2008, and received positive feedback from the Mod DB community. Pinchbeck had no intention of selling it commercially, but game artist Rob Briscoe (now at Valve) asked about giving the game a visual overhaul. "He'd just come from working on Mirror's Edge, and I was like, 'The Mirror's Edge artist wants to do free visuals on our mod?" Pinchbeck remembers. "OK, then!"

That led to Jessica Curry (The Chinese Room’s co-founder, and Pinchbeck's wife) re-recording her soundtrack with real instruments - and by then it made sense to try to make a little money. Yet even after securing the necessary capital from Indie Fund, ambitions remained modest.

"We just hoped we'd break even and Rob and Jess could get paid," Pinchbeck says. "We weren't anticipating it being the title that it was. The idea of it topping a million units is just madness." If certain segments of the market weren't ready for these games, then the video game industry - which was going through a period of rapid change in terms of both technology and business models - definitely was.

Online distribution was crucial to these games' success, and by 2012 a number of indie games had established themselves on console and PC digital stores. "Not having to get your game into Walmart is huge, right?" Dallas says. "Being able to make games for smaller audiences allows you so much more flexibility." From there it was effectively a case of 'build it and they will come', he says. "Once there were more walking simulators, players began to desire them. I guess the audience had to be bootstrapped into existence."

Save up to 52% on gaming magazine subscriptions for the perfect holiday gift

It's questionable whether this could have happened even a few years earlier. Chen was convinced to form a company by the positive responses to his Cloud project. (He recalls emails from around the world saying: "I cried at your game. Please tell everybody involved in this project that they’re beautiful people".) This was around 2006, in the very early days of Steam, and when Chen approached Valve, he struggled to attract any interest.

"They told me that the players on their platform only liked shooting games, so unless [we had] some shooting elements they would not publish our game." But things were evolving quickly, and Chen eventually signed a three-game deal with Sony, for PS3's nascent PlayStation Store. With Flower, the second of those games, Thatgamecompany had already proved the appeal of play centred on an emotional experience, especially among older age groups. By comparison, however, the impact of Journey would be meteoric, causing the whole industry to sit up and pay attention – and affecting some players surprisingly deeply.

Chen was prepared for emotional responses. "When we brought 25 testers in to play the game, several months before we shipped, three of them were crying [at the end]." But some of the feedback after release went beyond even what he could have imagined, especially when it came to the game's finale, in which the travelling protagonist collapses in the snow near the top of the mountain.

One person who had previously been in an accident that had left them clinically dead for two minutes told Chen that this was the closest replication of that near-miss they'd experienced in any medium, while other messages explained that Journey had helped their senders deal with grief. "People who play the game tell us how it almost has a therapeutic effect," Chen says. "And every now and then they play it because it gives them hope, it gives them some kind of relief."

Changing attitudes

With this feedback also came requests, Chen says, such as families asking for a splitscreen mode so they could play Journey together. These requests helped form Thatgamecompany's next project, Sky: Children of Light (which Chen also refers to as 'Cloud game 2.0'). By the time that game finally emerged into the light, in 2019, a lot had changed. In the intervening years, many games had followed in the footsteps of these first wanderers.

2013 brought Gone Home, Proteus and the commercial release of The Stanley Parable, another game that started life as a Half-Life 2 mod. The Vanishing Of Ethan Carter and Ether One came a year later; then in 2016 Firewatch and That Dragon, Cancer, picking up the thread of Thatgamecompany's emotional experiences. It's perhaps no surprise, then, that Sky's launch was hardly met with any of the same negative reaction.

"It's totally to be expected," Chen says – not least because the market has matured since Flower and Journey were released, with the audiences of 2009 and 2012 now more prepared for different kinds of culture. "It takes time for people's tastebuds to be stimulated," Chen says. "For them to realise they actually prefer this flavour."

Dallas also saw a huge shift in attitudes, even in the shorter gap between The Unfinished Swan and 2017's What Remains Of Edith Finch. The critical response to the latter was glowing, and any remaining hostility was much more muted. "I didn't get the sense that anyone was upset that this game existed," he says. "Maybe people were just exhausted, and they were like, 'Ah, another one of these things.'" The game was also free of that previous baggage of being compared to Portal. "We didn't have to explain things," Dallas says. "We didn't have to justify our existence. It's nice to feel like people accept your existence."

Pinchbeck noticed the change even in 2015, when The Chinese Room released Everybody's Gone To The Rapture. It helped, perhaps, that this title acted as something of a riposte to the common criticism of these games that "you could just do this as a film", as Pinchbeck puts it. Rapture told its story in nonlinear fashion, letting players discover it as they explored the game's abandoned English village. Pinchbeck calls it "the most important of the stuff we were doing around then", for precisely this reason - but it was also the point where the studio started to look to a different future, beyond the walking simulator.

"I think we felt like, that's as far as you’re exploring that direction," Pinchbeck says. Indeed, 'pure' walking simulators have become less common in recent years, at least in part, Pinchbeck believes, because their qualities have been incorporated into a host of other genres. Those quiet moments he'd identified and expanded into Dear Esther have become prominent in the biggest releases.

He points to the "seismic shift" between Guerrilla Games' Killzone titles, the last of which was released in 2013, and 2017's Horizon Zero Dawn as an example of how things have changed. "Story and quiet moments and reflection and all that stuff in isolation is quite an accepted core part of a game designer's toolkit, in a way that maybe it wasn’t in 2010." Today, The Chinese Room is a very different company, having downsized in 2017 before being acquired by Sumo Digital, and it's more interested in the potential of interactive storytelling than any particular kind of delivery.

"Will we ever make another game where you walk very slowly with limited interaction?" Pinchbeck says. "Don’t know. It's not what we are making. But is what we are making focused on gaming as an emotional experience, atmosphere, story, world? Absolutely. We're not going to make Bubble Pop."

Impact

"[After Journey] quite a few games were able to make very touching stories and deal with serious subjects using gameplay. I feel pretty good to be [among] the first penguins that went that way."

Jenova Chen

We have one final question for all our interviewees about the legacy of their 2012 releases. Did they help change our ideas about what constitutes a video game? Pinchbeck is unequivocal: "No." It's worth noting again that these games were never intended to replace what had come before, despite what some players might have believed, and Pinchbeck is still obsessed with first-person games of all stripes, just as he was when he first played Doom. "Esther was just another way of exploring that," he says. "I’m very proud of Esther and what we did with it. But also I'm aware we were in the right place at the right time, when experimental games were getting a lot of visibility."

Dallas is similarly pleased with the evolution of games over the past decade, with more novel experiences coming to the fore. "For me, selfishly," he says, "I’m thrilled about it because it means that all kinds of oddball games can exist and find a home." And perhaps, he adds, perhaps Giant Sparrow has encouraged more people to embrace these oddball ideas. "I hope we've been somewhat helpful, just because we make games that are intentionally surprising, and try not to be frustrating, and we've helped to bring more people away from more traditional experiences to experiment with something new."

For his part, Chen still feels the weight of Journey's success, as if he's been living in the shadow of its peak ever since. "When we won game of the year [awards]," he says, "a lot of us thought, 'Well, life is going to be downhill from this point.'" In part that's because Journey was itself a lightning-in-a-bottle product of torturous development, which Chen has no desire to relive. But it may also be that it's far more difficult for any game to have that impact nowadays, if only because Journey and the class of 2012 helped fill in so many gaps in the lexicon of game design.

Chen can see the DNA of his best-known work in many emotionally charged games since. After Journey, "quite a few games were able to make very touching stories and deal with serious subjects using gameplay," he says. "I feel pretty good to be [among] the first penguins that went that way."

This feature first appeared in issue 370 of Edge magazine. For more fantastic features and interviews, you can pick up a single issue at Magazines Direct or subscribe today.

Jon Bailes is a freelance games critic, author and social theorist. After completing a PhD in European Studies, he first wrote about games in his book Ideology and the Virtual City, and has since gone on to write features, reviews, and analysis for Edge, Washington Post, Wired, The Guardian, and many other publications. His gaming tastes were forged by old arcade games such as R-Type and classic JRPGs like Phantasy Star. These days he’s especially interested in games that tell stories in interesting ways, from Dark Souls to Celeste, or anything that offers something a little different.