From Shogo to Shadow of War: Charting the chaotic, creative history of Monolith Productions

The story of Monolith Productions is one of eclectic games and technological trailblazing

When you try to imagine how the developers behind Blood, one of the most gloriously gory games of the nineties, first came together, the last thing that springs to mind is a games studio known for titles like Millie's Math House. Perhaps the placid nature of educational games development caused a pressure-cooker of wild ambition among a few of its developers, because it was at Edmark that the seven founders of Monolith began planning their break into the games industry.

It all stemmed from a love of gaming. One of the founders, Toby Gladwell, recalls those early experiences. "We'd been playing Doom, we came together with a love of games and wanted to take a stab at building them," he tells us. "Maybe it's the arrogance of being in our early twenties, but at the time we thought we were the most creative group of our time."

Naturally, several of the founders wanted to jump straight into game development, but Jason (Jace) Hall – a charismatic big-thinker who would procure many of Monolith's most lucrative deals – had another idea: a MegaMedia CD. The idea was quintessentially Nineties. An innovation called Redbook Audio meant that videos, game demos and music could all be stored on the same CD. Jace created some videos and music, and Brian Goble contributed a special version of his game Microman, among other things. In 1994 Jace left Edmark to become Monolith's evangelist, using the Monolith CD as a gospel to attract the people that mattered.

It didn't take long. Jace impressed Microsoft, which just so happened to be working on the first iteration of DirectX – an API that would unlock the dormant power of PCs for gaming. Soon after that, the cofounders of Monolith left Edmark and piled into the prestigious compound of Microsoft for some contract work on Windows 95 gaming CDs. Monolith cofounder Garrett Price remembers this pivotal moment. "Windows gaming didn't exist then, it was all DOS," he tells us. "We left Edmark on a prayer – it was way scarier for Brian [Bouwman] who had a child at the time, but the rest of us were like 'We're young, let's do this!'"

The Monolith team's arrival at Microsoft coincided with another seismic moment in software history. "We'd been there a week when Windows 95 shipped. It went gold, and I remember it clearly because I was standing outside, and about two or three thousand people came running out of the buildings from across the way," says Toby. "It was like a stampede."

The Monolith team worked "out of a couple of closets" at Microsoft, making sample CDs while Jace continued to make contacts in the wider industry. They put all the money from their Microsoft work into the Monolith start-up pot. Jace's ever-growing network of contacts paid dividends too, when a Japanese company called Takarajimasha invested a sizeable amount of money into Monolith. Later that year, the Monolith team moved out of their Microsoft quarters to their first office – though perhaps 'compound' is a more fitting description.

"We leased a bunch of buildings in this office park," says Garrett. "I remember walking through it with my wife and she asked 'How are you ever gonna fill all these up?' We just began rounding up our friends from other companies. We almost instantly had this whole crew." With the studio complex set up in 1996 – complete with sound studio and other high-end extras – it was time for Monolith to make its first homegrown game. Garrett was Monolith's original artist, and presented the rest of the team with a shelved project from his art school days. It was Captain Claw – an anthropomorphic pirate cat who fought through packs of 'cocker spaniard' dogs in his pursuit of the Amulet Of The Nine Tails.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"I was obsessed with New Wave music, Adam And The Ants, all that stuff, so that whole romantic pirate outfits thing. This was right before Earthworm Jim came out too, so a good time for irreverent weird characters," Garrett tells us, proud of his pet project that would kickstart Monolith's resume.

Humble beginnings

If you want in-depth features on classic video games delivered straight to your doorstop, subscribe to Retro Gamer today.

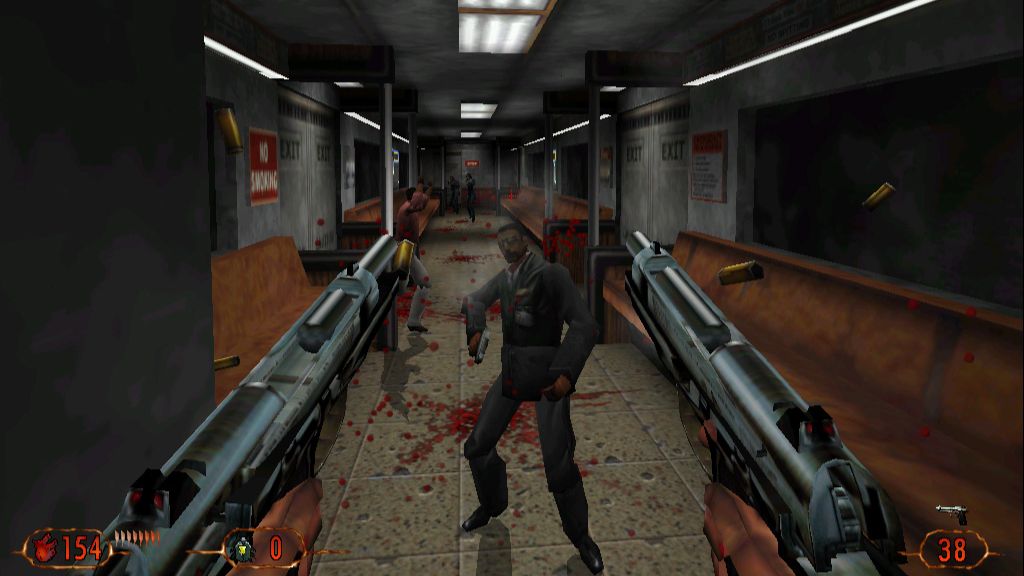

Right from the start, Monolith was a many-tendrilled beast, always finding itself on the technological boundaries of the medium. While working on Claw, Monolith acquired Q Studios, which was working on the last – and arguably greatest – of the Build engine shooters, Blood.

"Q Studios was launched by our friend Nick Neilhard," Garrett recalls. "In this whole pedal-to- the-metal thing, Jason was like 'Let's just acquire Q Studios, let's get Nick in, let's give him stock, let's make him a part of this too.'" Blood was a much-loved game, eventually replacing Doom as the go-to deathmatch game at Monolith. It had comical Evil Dead-type dialogue and detailed sprites based on models sculpted by Kevin Kilstrom.

"He got a sculpting degree from Wazoo and could make these amazing movie masks," says Garrett. "Literally cinema quality stuff. He sculpted all these characters and maquettes for Blood." Beloved though Blood was, it represented the end of an era in PC gaming, as 2.5D graphics made way for 3D-accelerated ones. Monolith knew it had to be part of this revolution, and even as Blood was still in development there was already a team dedicated to building an in-house 3D engine.

In 1996, Monolith received the Rendition Verite V1000, one of the first 3D-accelerated video cards. This heralded the birth of DirectEngine, which would morph into LithTech – the engine that Monolith continues to use to this day.

But the early going with 3D wasn't easy. This was unfamiliar technology, it was expensive and it would take a few years for Monolith to find its footing with it. The stark visual contrast between the handcrafted pixel art of the original Blood and the rudimentary 3D graphics of its less-loved 1998 sequel, captured this tension.

"Both Blood 2 and Shogo were built with LithTech. We faced a ton of challenges going from 2D sprites that have lots of detail to 3D modelling which at the time was rough – triangle throughputs were very low, texture size was tiny," admits Toby. "There was a quality bar which was really difficult to hit." Monolith continued releasing games based on the tastes of the team rather than the trends of the market. Shogo: Mobile Armor Division was a mech shooter inspired by the team's love of manga.

"We had an exchange student and she had given us some Gundam magazines, Dancouga and other things that I'd draw inspiration from for Shogo," Garrett remembers. "The concept artists just blew that out and made it amazing." Then there were more humble 2D efforts. Get Medieval was an irreverent dungeon crawler based on Gauntlet, which many of the devs played in arcades growing up, while Gruntz was a real-time strategy game inspired by the team's obsession with Warcraft II.

Monolith was prolific between 1998 and 1999, releasing nine games as a publisher and developer. The studio was self-publishing, it was publishing for others, it had a dedicated engine department, and even had a motion-capture services wing called Monolith Studios. The idealistic young company was beginning to overstretch itself.

"We had a lot of overheads at this time, so unfortunately we did have to take steps and shrink the company," Toby explains. "It was extremely difficult for us to go through, and maybe the first time we had to take a collective breath, sit down and talk about where we were going and focusing on the right things for the future. We grew too quickly, and we tried to do too much."

This is the point where Toby believes the company culture shifted. The focus around games tightened, which also meant that some of that chaotic creativity had to be reeled in towards a more managed, structured model. Monolith Studios and the publishing side ceased operations. Both Toby and Garrett admit they're most fond of the earlier, more carefree days of Monolith, but the next few years would be some of the studio's fi nest.

In 2000 it released its first game on the new LithTech 2.0 engine, Sanity: Aiken's Artifact – a top- down action game casting you as a psychic special agent voiced by rapper Ice-T. While it wasn't Monolith's most famous game, it marked a breakthrough for the LithTech engine, propelled by the launch of Voodoo 2 graphics chips.

"Final Fantasy 7 had recently come out, and I was blown away by the effects that it had," says Toby. "It made us realise we could just build a system that lets artists do these special effects, and it became the basis for Sanity: Aiken's Artifact. That effects system actually got used in pretty much all our other titles."

Sound strategy

"We grew too quickly, and we tried to do too much."

Toby Gladwell

Sanity laid the groundwork for what would become two of Monolith's most beloved games: sassy Sixties-themed shooter No One Lives Forever and Aliens Versus Predator 2 – arguably the best ever use of the Alien IP in video games. These games marked the maturation of the studio and its engine technology they had been working on over the previous four years.

The two games' contrasting tones of campy irreverence and cold sci-fi horror – witty originality and loyalty to a beloved IP – embodied the omnidirectional spirit that was such a key part of Monolith's identity. The success of Aliens Versus Predator 2 solidified Monolith's Warner Bros connection, which would lead to the (ill-fated) Matrix Online and ultimately to the much less ill-fated acquisition of Monolith in 2004. Before the acquisition, there was still time for a much-improved No One Lives Forever sequel and Tron 2.0, which was again as much a passion project as a lucrative job.

"Tron was cemented in our childhoods as the coolest thing ever, so we got this opportunity to build a game in the Tron universe and even meet Sid Mead – talk about fanboyness," Toby recalls. "We were able to leverage our knowledge building shooters to make a game that was really well-received."

Monolith would remain a forward-thinking developer under Warner Bros. FEAR (2005) pushed the envelope of AI and graphical prowess, while Middle-earth: Shadow Of Mordor's nemesis system was deemed to be such an asset to Warner Bros that it was recently patented. But that gets to the heart of why Monolith's acquisition was bittersweet.

While the legacy and talent crossed over into the new era, the nemesis patent is indicative of how great game design can get tainted by the cold calculations of publishers, which are often at odds with the interests of the gamer. That first decade of Monolith, on the other hand, was driven by gamers who happened to be an exceptional team of developers, and we were all winners from it.

This feature first appeared in Retro Gamer magazine issue 219. For more excellent features, like the one you've just read, don't forget to subscribe to the print or digital edition at MyFavouriteMagazines.

Retro Gamer is the world's biggest - and longest-running - magazine dedicated to classic games, from ZX Spectrum, to NES and PlayStation. Relaunched in 2005, Retro Gamer has become respected within the industry as the authoritative word on classic gaming, thanks to its passionate and knowledgeable writers, with in-depth interviews of numerous acclaimed veterans, including Shigeru Miyamoto, Yu Suzuki, Peter Molyneux and Trip Hawkins.