26 years later, Codemasters' Chris Southall talks Colin McRae Rally: "We wanted to do something that was an authentic rally experience for the hardware of the time"

Feature | The Evolution of Colin McRae Rally: Retro Gamer talks with former Codemasters creative Chris Southall on the racing series' legacy

In the Eighties, computer games required replay value to sell and coin-ops had to keep players' games short to be profitable, so it stands to reason that the earliest attempts at 3D rally games for PCs differed from their arcade equivalents. Take the 1988 PC title Lombard RAC Rally. It was hardly realistic, but it replicated actual courses and entire seasons. The 1989 coin-op Big Run, by comparison, was Out Run with rally cars.

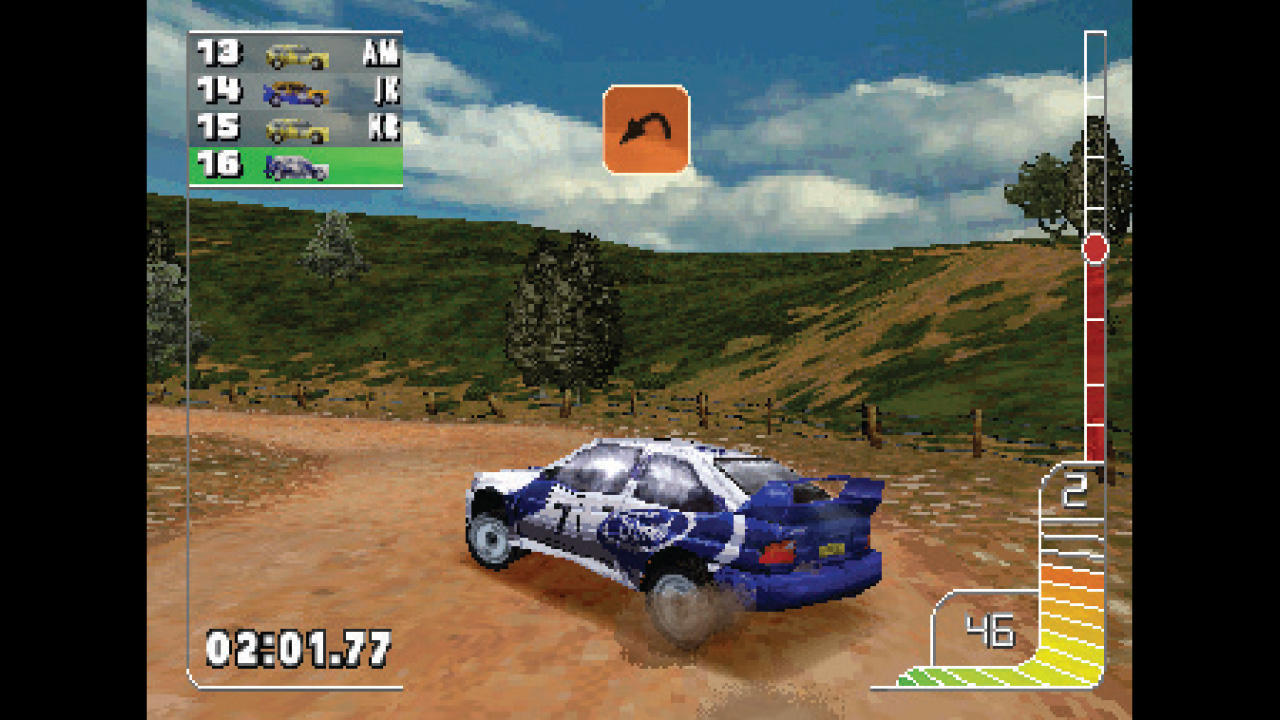

By 1996, console games had a foot in both camps. They required longevity, but they were also expected to provide an arcade-like experience. This explains the thinking of a Codemasters team whose project took inspiration from both arcade and PC rally titles, as former Codemasters coder Chris Southall remembers. "A lot of us on the team were big Sega Rally fans," Chris notes. "We had a Saturn in the office with one of those early steering wheels, and we played a lot of Sega Rally at that point. There was another game on PC that we spent a lot of time playing called Network Q RAC Rally Championship. It was quite hardcore with long end-to-end special stages, and we referenced that as well. We really just looked at all of the games that were out there. At that point, the strategy at Codemasters was very much around finding a name and attaching a game to it, so that was an inspiration for Colin McRae Rally as well."

Before securing the popular rally driver for their game, foundations were laid for not just it but also a Formula 1 racing title, and this required a division of labour. Those that remained working on Codemasters' rally title were then sent out to do research. "Before we started the game, a few of us in the design department were working on 3D vehicle physics," Chris recalls. "That then became TOCA and Colin McRae Rally; we split the team up at that point. When we were just starting to work on Colin McRae Rally, Richard Darling sent us to a rally school, where we all drove cars around a forest stage. The point of that was that we wanted to do something that was an authentic rally experience for the hardware of the time, even though it was going to be an arcade-y game."

Rallying cry

This feature originally appeared in Retro Gamer magazine. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Retro Gamer or buy an issue!

The decision to strike this balance between simulation and coin-op-style gameplay was partially down to what was popular with the team's target audience. A second consideration was the technical limitations of their target console. "By the nature of the PlayStation, and the kind of the games that were on there, it didn't seem right to do a full sim," Chris reasons. "It also wasn't possible with integer point maths at that time. So we weren't going to have 25-minute stages or anything like that, but we were trying to make the environments feel realistic and we spent a lot of time modelling how loose surface friction works versus traditional tarmac. We modelled the tracks so that their profiles mattered, and being able to go off the track was part of the experience as well."

Just as important as the game's modelling was the look of its locations, which were based on those of the official World Rally Championship. As the internet and digital photography hadn't yet come of age, this required globetrotting and skilled artists. "We sent people to different locations to take reference. That was important," Chris emphasises. "One of my best friend's brother happened to live in Kenya, and that was one of the locations in the game, so we sent him around Kenya, driving and taking references, which he then sent back to us. Sometimes we would send people working on the track designs as well as artists. When they stood on the roads they got a better insight on how to construct the tracks in the game. Then on the other side, a lot of clever people in the art team optimised things and did as much with the textures as possible to get as much variation as we could."

As well as getting reference for Colin McRae Rally's environments, the team working on the project got the star of their game and his co-driver into the studio to do voice recordings. The team also got pointers on the implementation of their game's cars. "Both Colin McRae and Nicky Grist were pretty involved," Chris reviews. "I remember working on the Rally School mode, and I wrote a list of all the things that Colin needed to say. When he read them back you could tell he wasn't a voice actor! He also gave us advice on how the cars handled, and it was just really cool to understand that stuff. Nicky would do the pace notes, which were for every corner or bit of the track that you came to."

Starting line

While Colin McRae Rally came together, a rival firm beat Codemasters to market with a PlayStation rally game of its own. But rather than worrying the Colin McRae team, it convinced them that their decision to pour time into modelling was the right one. "When V Rally was released we were in mid-dev on Colin McRae Rally," Chris recollects. "We didn't think they got the sliding/hand brake right, so in general we were reassured of where we were at on the handling model versus that. Colin McRae Rally was realistic enough rather than being a game that didn't really obey the laws of physics."

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

During pre-release marketing for Colin McRae Rally, Chris was reminded of the skill involved in racing real-life rallies by its leading man. Naturally, the game was far less demanding, but the experience reassured the coder about his team's focus on authenticity. "I remember doing a press tour in Germany where everybody was driving around a karting track," Chris reflects. "It was ridiculous, because Colin was just lapping me. It was night and day how fast he was versus a normal human. Having that sort of connection was great. I mean you couldn't simulate it in an arcade-like game, but it was really important to have that and to have pulled it through into something that hung together for the player."

This last point was borne out by Colin McRae Rally selling in its millions on the PlayStation and PC. An online community subsequently grew out of the PC version's networked mode, which then fed into features chosen for a sequel. "We found that with the PC version of the first game having multiplayer over dial-up connections that people were setting up championships and playing together a lot," Chris points out. "I think the PC multiplayer was where the multi-car Arcade mode in Colin McRae Rally 2.0 came from. We leant into it a little with its multiplayer stages as well, because you had ghost cars in those, although they were very much times-based."

Second lap

Another difference between Rally 2.0 and the original game was that initially you could only race in stages held in certain countries. The remaining nations featured in the game could only be unlocked by progressing through its Championship mode. "You wanted people to spend time with your game, and just giving everybody everything at the beginning wasn't necessarily the best thing to do," Chris explains. "Having people work to unlock content encouraged them to appreciate it more. It was about skill as well. If you had a later stage that was really tough, and you gave someone that on day one when they didn't have the skill then they weren't going to enjoy it. Whereas having players practice easier stages let you do more with the later track designs."

The follow-up's fresh features also included a Challenge mode, which unlike the main mode, involved a knockout tournament rather than a league. Although this option was new to Rally 2.0, it had actually been intended for the original game. "The first game was really good, but there was a load of stuff on the drawing board that we didn't manage to get into it," Chris reveals. "The different modes and challenges were some of those things. The Knockout mode was an obvious thing to have just from a player perspective, as some might not want to have an experience that was more drawn out. Someone who stopped playing the main mode because they were a bit stuck would also have thought it was great to explore the other modes."

One of these alternative challenges saw players racing in classic cars. The criteria for the selection chosen was partially driven by which would contrast Rally 2.0's contemporary vehicles, but commercial considerations were also a factor. "Everyone on the team was a car geek, so it was just an obvious thing to have different categories like classics," Chris enthuses. "The selection of classic cars was a combination of what people liked and us wanting to have variety. Going back to the Mark II Escort meant you got a rear-wheel drive car versus a four-wheel drive Quattro with all the power that had. It was just interesting to have that variety. It was also what we were able to use from a licensing perspective."

Next-gen racer

Restrictions of a more technical kind initially limited an aspect of Rally 2.0's aesthetics, but thanks to clever coding, and encouragement from a Codemasters founder, a way was found to overcome them. "We just couldn't get dirt on the cars, but Richard Darling was adamant about it," Chris sighs. "He really pressed the programmers working on that stuff. They were very talented guys, and so they did some technical wizardry to get mud spatter happening on the cars. It sounds ridiculous these days, but it was quite technically challenging at the time."

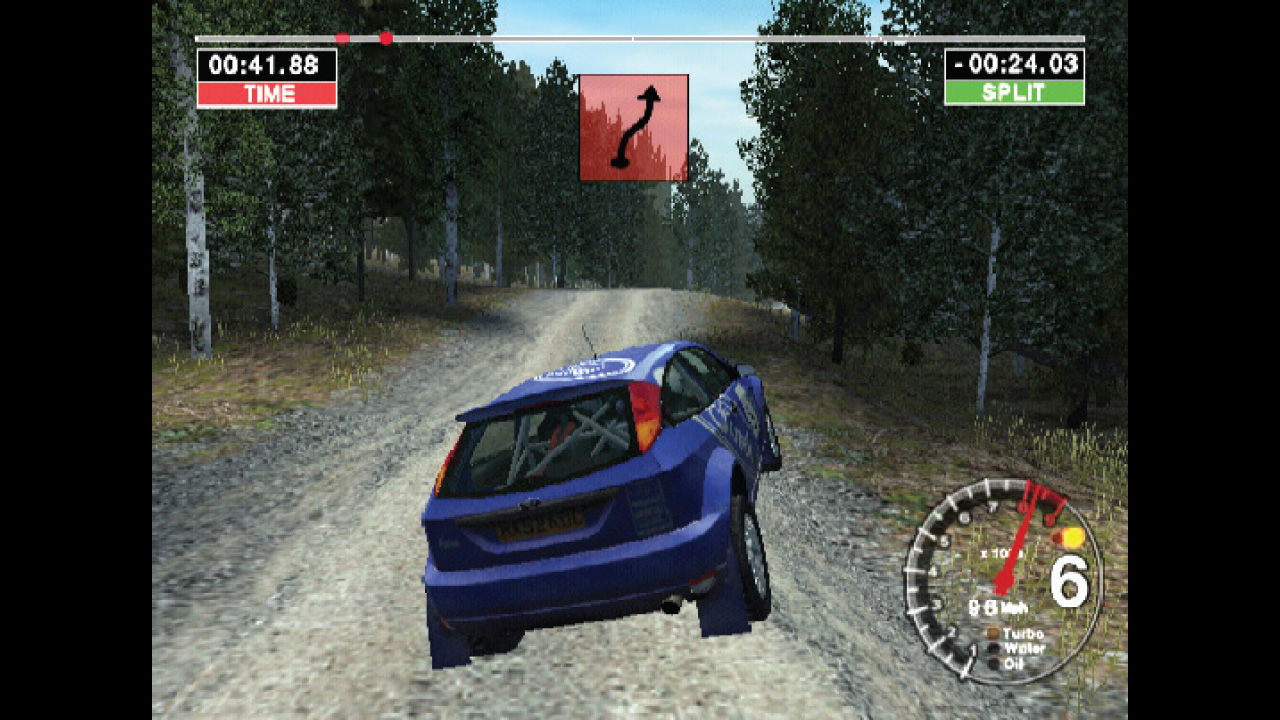

More technical challenges followed as the success of Rally 2.0 led to Colin McRae Rally 3. Unlike its predecessors, it was designed for the PS2, and learning to code for the powerful new system resulted in a more realistic game with fewer modes. "That probably came from a technical focus on getting the game engine stood up," Chris reckons. "We were writing our own game engines, and it was the jump to PS2. It took some of the engine guys quite a long time just to get polygons on the screen on the PlayStation 2. It was not super easy to program for out of the gate, even though it had a lot more horsepower than the PlayStation. So I think the focus there was naturally far more towards simulation."

One addition to Rally 3 was an upgrade system where performing well in rallies was rewarded with performance parts for your car. These were chosen for the player rather than them getting a choice, which made sense for a number of reasons. "I think that was really just to give simplicity to the upgrade path," Chris considers, "and to allow us to tune the game to what the car was doing rather than having a wide variation due to different parts being equipped. If you put a huge engine into a Mini then you would have torn the drivetrain to pieces, and it wouldn't have been able to turn around corners. With each car there was a range through tuning it, but it was also important not to go outside the range of plausibility."

Gearing up

"It didn't change the ethos from the first game, which was that you were supposed to feel like you were rally driving."

Judging by the response to Rally 3, its leaning towards simulation and linear upgrades were popular choices. Spurred on by this and a better understanding of the PS2, the team creating Colin McRae Rally 04 incorporated real-world physics. "The physics were getting more advanced, and it was always down to authenticity, but with fun in there," Chris assesses. "It didn't change the ethos from the first game, which was that you were supposed to feel like you were rally driving. But our aim was still to have an accessible game that was realistic rather than being a sim. Because it was our second Colin McRae title on PS2 we had more time to develop things. Like the loose surface physics engine, where you had different grips when your wheels were spinning or not."

One other feature that there was time to develop for Rally 04 was an Expert mode with a forced cockpit view. Another mode showcased insanely powerful cars, and two more focussed on 2WD and 4WD models. "It was fun for us for the sim to be locked into the cockpit view, because that gave you the most authentic feeling," Chris observes. "We spent a lot of time tuning the views behind the car, but actually sitting in the car was its own thing. With the massively overpowered banned Eighties cars, well you want to do things with videogames that aren't very possible in real life! Then there was a lot of affection for both the 2WD and 4WD groups, so those were just obvious modes to include."

A final feature of note in Rally 04 was partly done just for laughs, although ironically the end result represented a serious racing challenge. This came in the form of a set of bonus cars, which included a Citroen 2CV and a Ford Transit Van. "I just think at that point it was appropriate," Chris remarks. "You wouldn't have put them in the first game probably, because people would wonder what the hell was going on. But by the fourth game the audience just thought it was fun, and it didn't make people question what kind of game it was. So I just think it was just a fun thing to be able to do."

One more go around

As with the earlier titles, the highly rated Rally 04 led to a sequel – Colin McRae Rally 2005. Chris didn't have a hands-on role on the project, but he took an interest in the fifth game in the series and approved of it pitting you against Colin McRae in one mode. "I don't know if people liked that or not, but it was an obvious idea to race Colin," Chris contemplates. "You were playing as Colin in Colin McRae Rally 3, where you were locked into racing in the Ford Focus, so it was an interesting idea to race against him in Colin McRae Rally 2005."

Other areas where Rally 2005 improved on the earlier Colin McRae titles were with the customisation it allowed and its highly interactive environments, the latter of which compared favourably with the original PlayStation game that kicked off the series. "It was the same story with the rendering engine as it was with the physics engine – it was all written by us, and more things became possible as time went on," Chris highlights. "So things like the ability to change driver names and put them on the cars, and trees shaking and leaves falling on the vehicles. We couldn't do anything with the track sides other than 2D facing planes in the first game, but by the fifth game there was the capability to be able to do more with the environments."

Although Colin McRae Rally 2005 was well received, its follow-ups partially and then completely dropped the Colin McRae name, and embraced other racing disciplines. Asked about Colin McRae Rally's legacy, Chris recalls an anecdote and singles out Rally 2.0 for praise. "I met this guy recently, and he was a big fan of Colin McRae Rally," Chris beams. "He claimed it saved him from crashing not long after he had started driving, because it was wet weather and he knew to react accordingly after playing the game. We spent a long time internally playing that, and it's always a good sign when you see your team playing something in their spare time that they're spending their whole life making. It was the same with Colin McRae Rally 2.0, but there was a lot of stuff in it that we had more time to finesse, so I would say that it's one of the best titles in the series, and it's absolutely still fun to play."

Ready to put the pedal to the metal? Check out our best racing games list for what to play next!

Rory is a long-time contributor to Retro Gamer Magazine, and has contributed to the publication for over 10 years. He also contributed to GamesTM magazine, and once interviewed Hunt Emerson.