"We would look at all the American RPGs and the JRPGs at the time and just go, 'Right, if they're doing it, we're not": Peter Molyneux and John McCormack talk the development of Fable 20 years on

Feature | The Making of Fable: Celebrating 20 years, Retro Gamer talk with Peter Molyneux and John McCormack about the highs and lows of creating Fable

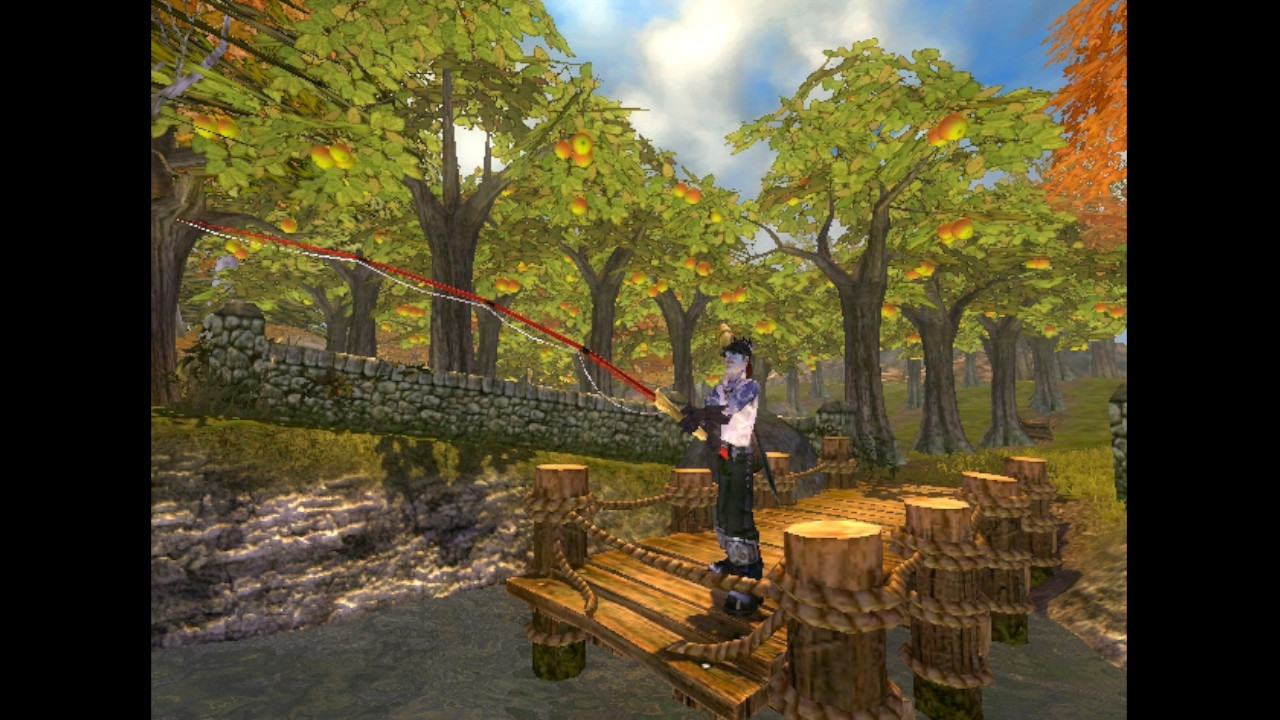

There are few releases which can be said to have had as much of an impact on the games industry as Fable, a title that upended the RPG rulebook by focussing on emergent gameplay rather than grand quests, all with a healthy dose of British humour. Its influence is plain to see in later games like Mass Effect, with its choice between good and evil paths, but its creation was far from smooth.

Peter Molyneux traces the origin of Fable back to the time when Bullfrog, the company he founded, was developing the 1997 PC game Dungeon Keeper. He recalls discussions with designers Mark Healey and Simon and Dene Carter in which they were "moaning about role-playing games and how serious they were", as well as how they were mired in statistics, which "took away from the delight of feeling that you were the hero and feeling that you were going on an adventure". Peter says it was these discussions that Simon and Dene would call back on when they developed the concept for Fable years later.

Bullfrog had been bought by Electronic Arts in 1995, and Peter decided to leave the company following the completion of Dungeon Keeper, after becoming increasingly dissatisfied with the corporate role he now found himself in, detached from game development. Other Bullfrog employees soon followed his lead, and by 2001 the studio had vanished, fully absorbed into EA. On his departure, Peter set up Lionhead Studios, which was initially run from his house, but soon established offices in Guildford, at the University Of Surrey Research Park. At around this time, Ian Lovett and Simon and Dene Carter also departed EA to set up Big Blue Box Studios, one of a number of 'satellite studios' that all reported to Lionhead. The idea was that each of these studios could work semi-independently, incubating their own game ideas.

Artist John McCormack, left behind at EA, recalls that Simon, Dene and Ian asked him to come over to Peter's house to view a tech demo built by coder Martin Bell. "I was sold on that immediately because it was an incredibly powerful terraforming engine," he recalls, saying that the plan was to use this engine for a fantasy RPG concept called Wishworld that would see epic battles between wizards. It was an easy decision for John to abandon the sinking Bullfrog ship and join the Big Blue Box crew.

Making a wish

This feature originally appeared in Retro Gamer magazine. For more in-depth features and interviews on classic games delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Retro Gamer or buy an issue!

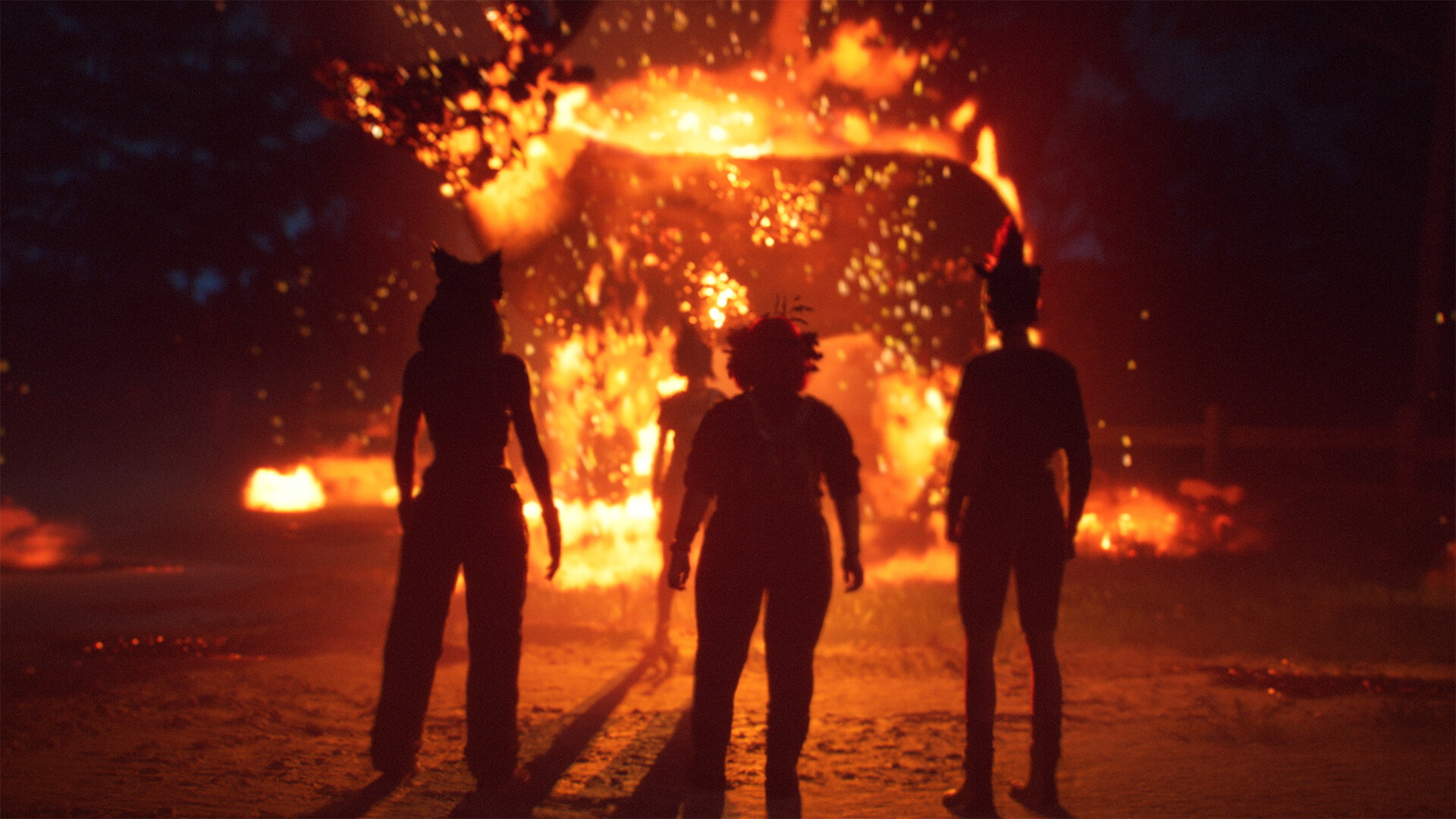

Wishworld didn't last long as a concept, however, soon morphing into what would come to be known as Fable – although initially it had the working title of Project Ego, which referenced the game's central idea. "One of the foundation stones of this world was you should be allowed to be whoever you want to be," says Peter, adding that the appearance of the hero would change over time to reflect their deeds in the world: they might grow horns if they veered towards evil, or develop a halo if they tended towards the good. This alignment could have been easily represented with numbers, but Peter says that this was something they were keen to avoid, harking back to those discussions about stat-heavy RPGs, "Why use numbers when you've got visuals?" The same idea would be used to great effect in Lionhead's debut title Black & White in 2001.

In another world, Fable could have debuted on the Sega Dreamcast. Peter recalls that in the early days of Big Blue Box, the president of Sega came to his house to discuss a deal, which was derailed by a dog owned by someone who was visiting. Peter remembers that a strange expression came over the president's face, "And then I happened to look under the table, and this Shih Tzu dog was shagging his leg," he says. "I think that was the end of our Dreamcast relationship."

Instead, Lionhead signed a two-game deal with Microsoft for Fable and BC, the latter of which was being developed by another satellite studio called Intrepid. John says the initial plan was for Fable to be a launch title for the Xbox, which was set to debut in Europe in 2002, but this plan was quickly abandoned once it became clear just how prolonged Fable's development would be. The deal "changed everything for us" says John. Up to this point Big Blue Box had been a studio of only around ten people who had been focussed on playful experimentation. Now, all eyes were upon them. "Suddenly we were making the game," says John. "Things started being scheduled, and we'd never even had a schedule before, we just made stuff."

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Planting the seed

Getting the project off the ground was a tall order. The engine and tools had to be invented from scratch, and the fact that Fable would debut on Xbox – when Lionhead and Bullfrog before it had almost exclusively worked on PC – added another headache. The PC benefited from constant improvements in memory and processing power, "But with a console, it's fixed," says Peter, and getting Fable's ambitious ideas to work within those constraints proved tricky.

"We had a sandbox of ideas and we understood what the world was, but we didn't have a story, we didn't have any kind of arc – we had lots of toys," recalls John. "And one of the main toys was an immersive villager reaction system, an AI system that was really complex [and] that ended up influencing the entire game, because it became less about going on adventures and more about what it's like to be a hero and have your actions affect people. That ended up [being] such a technical challenge that that was the thing that took the most time."

Getting the sandbox gameplay of Fable to work involved endless trial and error, says John, although it could also be joyful. "I've never worked on a game where everybody was crowded around people's desks laughing as much as we did," he says. Testing out all of the various possible interactions in the game would often throw up unexpectedly hilarious results, which the developers would sometimes account for by adding extra dialogue. "It was almost like the game had a life of its own and we were reacting to it," says John. "We built a world and it was talking to us."

John recalls that the movies Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal were big influences on Fable, as well as the Jim Henson TV series The StoryTeller, and the overall aim was to reflect the darkness of European fairy tales. "Dene in particular had a very clear vision of what was right and what was wrong for Albion," says John. "He's probably one of the strongest creative directors I've worked with."

Branching out

The distinctively chunky style of Fable's characters originated from character artist Damian Buzugbe, while John pioneered the look of the buildings. "We wanted everything to be grounded like a tree," says John. "The buildings are thicker at the bottom, then taper, then go back out." John also had a hand in designing many of Fable's monsters, and he says the team was encouraged to deconstruct fairy-tale creatures to give a reason behind their existence. So the Earth Trolls, for example, have been angered by the excavations and movements of humans, prompting them to rise out of the ground. The Hobbes, meanwhile, Fable's equivalent of goblins, were children who had been kidnapped and cursed before being left in a cave, which resembled "a really messed up daycare centre" says John. For such a funny game, Fable went to some very dark places.

From the very beginning, the goal was to make a "particularly British, dark, humorous fantasy game" says John, although they initially imagined it would have a niche audience. So Big Blue Box was surprised at just how much Microsoft bought into the concept, particularly the humour. "I don't think anybody in the team really understood the depth to how much Americans love Monty Python," he surmises. Indeed, Peter cites Monty Python And The Holy Grail as a particular influence on Fable, although he says a lot of the humour in the game simply arose from the freedom given to the player to do "ridiculous things", as well as the "slightly silly, over-the-top characters", rather than specific jokes. Fable's irreverent nature was a deliberate counterpoint to other games in the genre, says John, "We would look at all the American RPGs and the JRPGs at the time and just go, 'Right, if they're doing it, we're not.'"

Fable was such an ambitious project that by the end there were around 150 people working on the game. "I don't know whether Peter was too happy about it in terms of it being suddenly the focus of Lionhead, because it obviously meant that his projects that he was focussing on went on the back burner, and Fable took over everything, essentially," says John. Intrepid's BC game was cancelled, and one by one the satellite studios were absorbed back into Lionhead. "Pretty much everybody ended up on Fable," John says.

At first the coders at Big Blue Box were relocated to Lionhead's main office, and then eventually the entire satellite studio was shut down as everyone was moved to Guildford. "I missed the Godalming office," says John. "It was the perfect place to come up with Fable, because it was surrounded by fields, there was a creepy graveyard on the corner, we were right on a small river with a bridge, and barges would go by. It was really idyllic and picturesque, and the buildings were all Tudor on that main street. So we were just like, 'This is where you make Fable.' Whereas the centre of Guildford on a research park is not where you'd make Fable. It was very different, there was concrete everywhere and it was an industrial estate. You're just going, 'Yeah, I'm glad we never started it here, because it wouldn't have turned out the same.'"

Peter says there was no game design document for Fable, reflecting the studio's commitment to free-form exploration. But this dedication to foregrounding creativity and experimentation came at a cost. "Ultimately, at the end of the day, that meant the development time was quite long and protracted," he says. "There was lots of stuff thrown away, there was lots of stuff added at the last moment, and there were an awful lot of things which had to be done at an extraordinary cost of human endeavour." Peter reckons the crunch period for Fable lasted for around 18 months, with some members of the team working six or even seven days a week. "We were all kind of semi-destroyed at the end of it," he says.

A legend born

John says the crunch on Fable was "mostly self-imposed in terms of just love for what we were creating", but he adds that it was punishing. "It was a tough old time, and the issue around crunch was really that I was fine with it, except it would extend again. You know, the release date has been pushed six months, let's pluck up the energy and go again. And then it would shift another six months and we would go again." Peter says that one person made a serious suggestion that they should put a double bed into one of the meeting rooms, so that team members could have conjugal visits from their partners.

"For me personally, crunch was just a way of life," says Peter. "Ever since my first game, I've been crunching on every game, it just felt like this was a natural thing." He adds that when humans focus intently on something, whether it's a videogame or a new invention, "That creative focus does result in some astounding achievements. I think Fable definitely was one of those."

Fable was released on Xbox in September 2004, and although the reviews were generally glowing, one of the main criticisms was about the game's length. "I can clearly remember people saying, 'I started playing Fable on Friday and I finished it on Sunday,'" says Peter. John thinks that people's expectation of how long RPGs should be had been set by games like Final Fantasy, but Fable was less about an epic narrative and more about encouraging experimentation. "We wanted the lengthy part of it to be the sandbox," he says. "It wasn't about travelling to Mordor, it was about staying near The Shire."

The team addressed the criticisms with the release of Fable: The Lost Chapters for Xbox and PC in 2005, which added things like new areas, quests, monsters and weapons to the base game. But John thinks that people's fondness for Fable doesn't come from specific quests or fights: instead they remember the emergent gameplay, the things they made happen, like coming home drunk and being shouted at by their partner. "We put so much work into that, and thankfully it paid off, because that's what made the game unique," says John. "People made stories for themselves."

So defining is it, we'd say that Fable is one of the 10 RPGs that defined Xbox and evolved the genre! What about the next game in the series? We've got a everything we know about the new Fable game you can read now!

Lewis Packwood loves video games. He loves video games so much he has dedicated a lot of his life to writing about them, for publications like GamesRadar+, PC Gamer, Kotaku UK, Retro Gamer, Edge magazine, and others. He does have other interests too though, such as covering technology and film, and he still finds the time to copy-edit science journals and books. And host podcasts… Listen, Lewis is one busy freelance journalist!