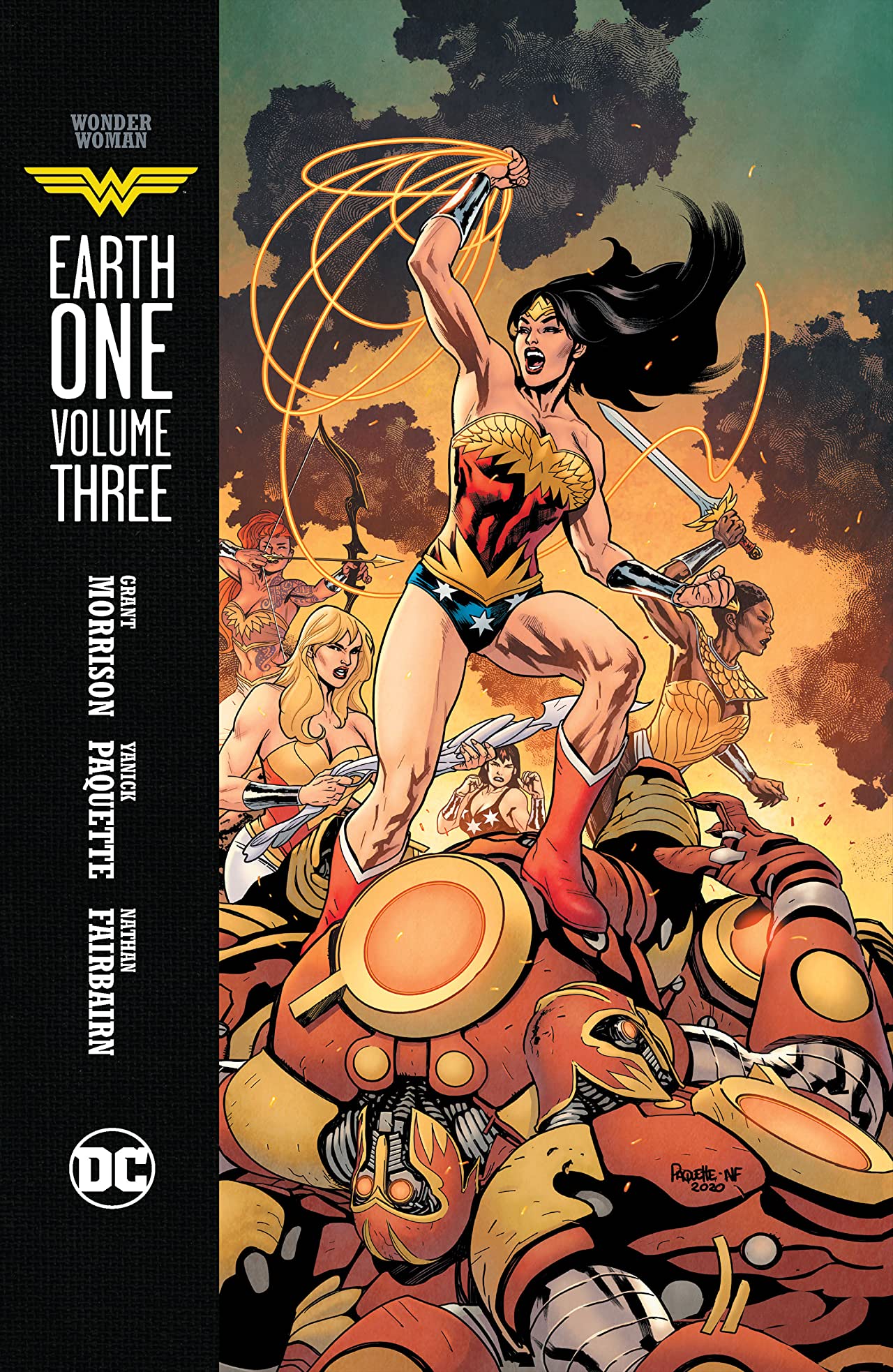

Grant Morrison's vision for Diana comes full circle with Wonder Woman: Earth One finale

Grant Morrison glows as Wonder Woman is finally able to "flower into the person that I saw in my head"

Six years after the first volume was announced, Grant Morrison and Yanick Paquette are closing the book on Wonder Woman: Earth One. And it's flowering, just as Morrison hoped.

Wonder Woman: Earth One Volume Three, which was released earlier this month, sees Diana dealing with the death of her mother, the incoming invasion of Themyscira by Max Lord, and the burden of making the world a better place. It all signals the end of Diana's journey through Earth One, but she's not the only one closing a chapter.

Just like Wonder Woman, Grant Morrison is a comic book icon. And now, like their version of Diana, Morrison is about to say something of a goodbye. With the ends of Wonder Woman: Earth One and The Green Lantern, Morrison tells Newsarama they are getting close to taking "some time off" from DC. But that's a discussion for another day.

Today, read our conversation with Morrison about this final volume of Wonder Woman: Earth One - the 1943 comic that inspired it all, and how they hoped to - and achieve - in breaking the mold of popular hero storytelling.

Newsarama: Grant, Wonder Woman: Earth One has carried the themes of utopia, bondage, and submission; all things famously written about in the works of William Moulton Marston, Wonder Woman's co-creator. How much of Marston's writing was on your mind as you were creating this story?

Morrison: A lot of it, in a sense.

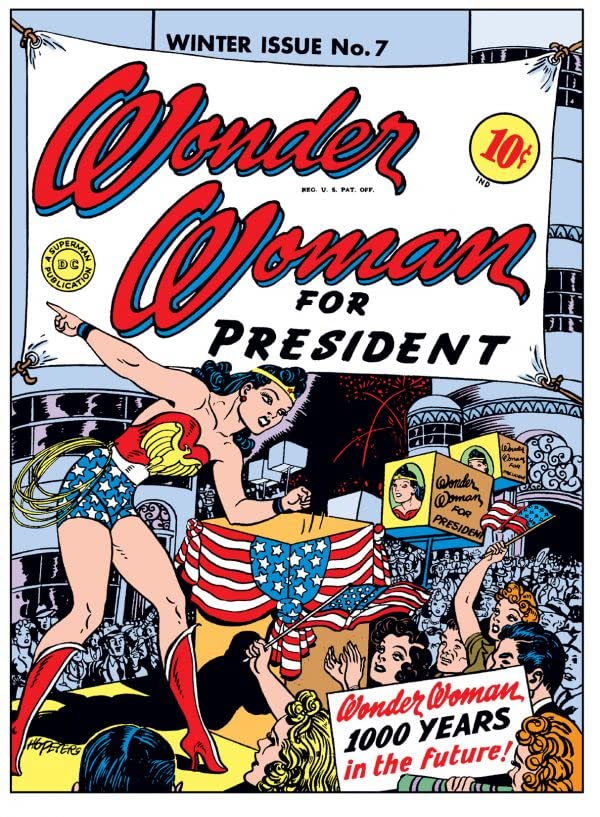

Way back when I started out on these three books, I was doing a lot of research. I had read a lot of William Moulton Marston stuff. There is a particular story, I think it's in Wonder Woman #7, which is probably 1940 or '41. It's set a thousand years in the future and I think it's called 'Wonder Woman for President.'

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

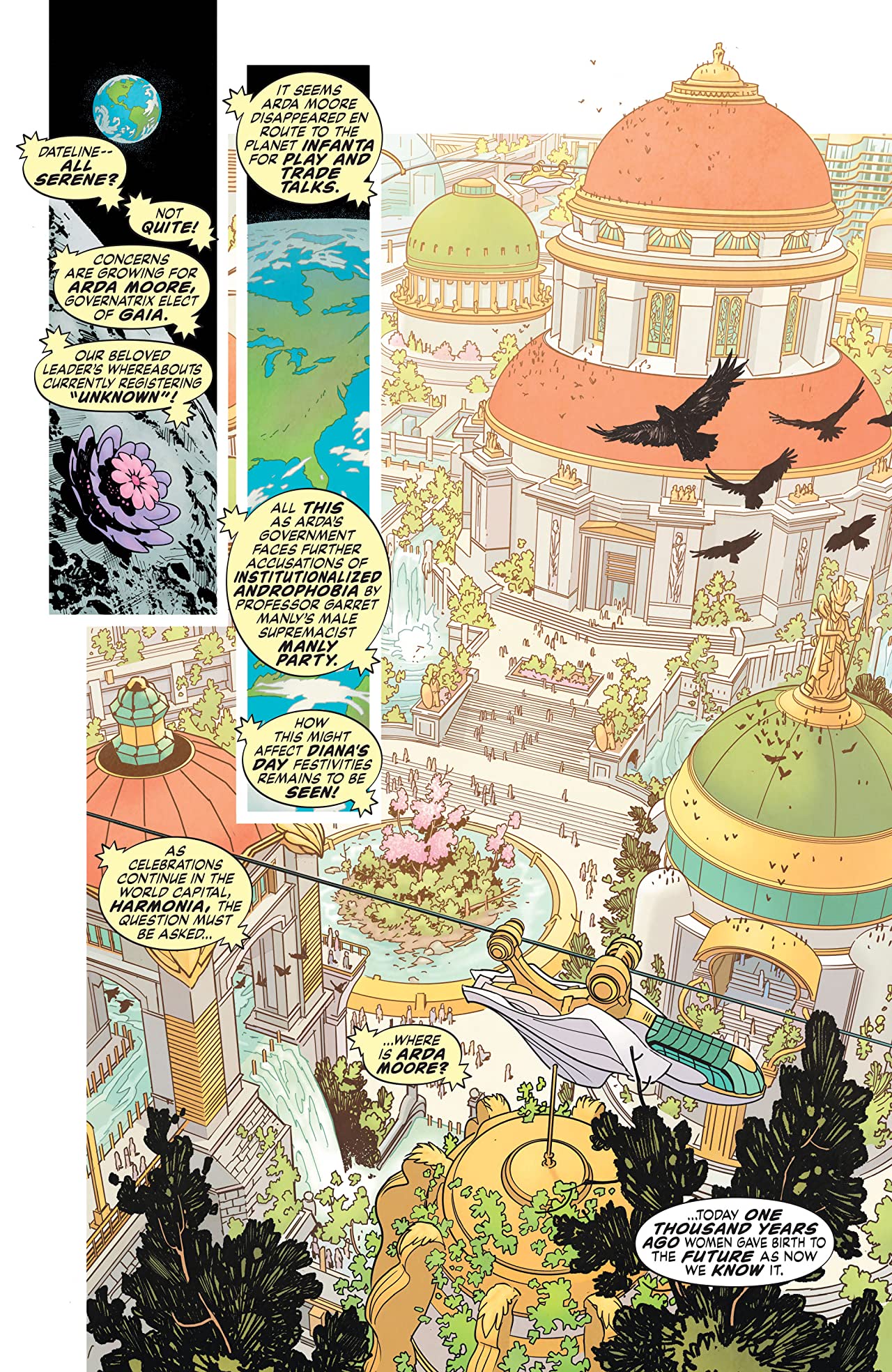

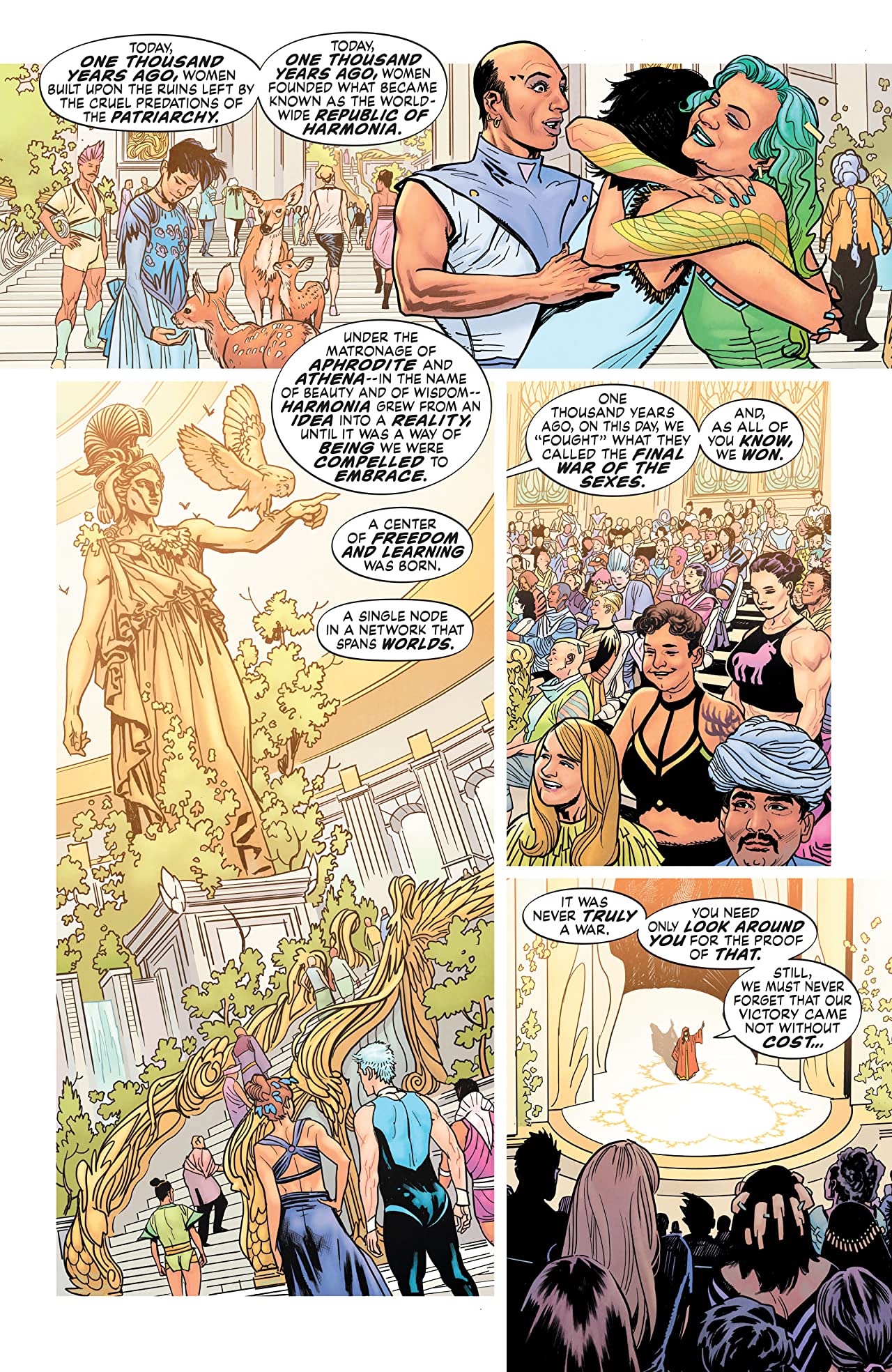

It presents this utopian society of Harmonia, and in that Harmonia there's one disharmonious element which is the "Manly Party,” or the "Purple Shirts.” I wanted to get to that point at the end of the book in the Earth One stories. I wanted to see the actual moment that the Republic of Harmonia became possible, and the story that led to that. So this is totally about Marston and about those ideas and how I've thought of them.

Nrama: Something else that I've read you wanted to do with this volume was avoid Joseph Campbell's predominantly male hero's journey. How would you say this volume does that?

Morrison: It kind of replaces a line with a circle. It replaces the Big Bang and the Birth of the Universe with more something that's more of a flowering.

I was getting down to the root of Amazonian culture and wondering what might be their philosophy, what would be their take on science. The Big Bang, for instance, is very much a masculine metaphor of Genesis. It happens with an explosion. I thought the Amazons might see that differently, see it in terms of natural growth and budding.

So I was thinking about ideas like that and how the Amazons would view the [hero's journey], and it's not about the Boy King seizing his inheritance and replacing his father. It's not about the overthrow of old structures, which is kind of our place in history, where we are right now. But in this future world, that's over. Those struggles and those big battles between opposites have disappeared.

Really what we're trying to get at is this underlying eternal circle. Diana's always a princess, and she's always a mother, and she's always a queen and so is Hippolyta. It's just a very different, timeless way of looking at the motion of the story. Diana's not here to replace her mother, she's there to recommit her mother.

Nrama: Speaking of Diana's character, there's a moment I really like for the beginning of the volume. Wonder Woman is prepping for battle and she asks the question, "How do we finish them with mercy?”

Why is mercy so important for Diana, even toward these unmerciful enemies?

Morrison: I think it's about the way she sees the world. She sees battle as a negative, something she's against. And when she realizes that there is going to be a battle, she decides that the battle will be fought on Amazon principles and not on the familiar battles of machines and men that we are used to.

She's not coming to destroy and make war. We kind of set it up to look that way, like the Amazons want to come up with their spaceships and swords and take over the world. But what she actually does is take over the world using, like you say, those principles of submission. She acts the part of a dominatrix to get the patriarchy at its core.

Also, she knows she's going to win.

They have technology that the human world has no version of in their arsenal. But what [Diana] has to do is not destroy, as most conquerors do, but to build on a base of what is real, and to ignore the things that are holding people back and holding the planet back. Yeah, she has an agenda, but it's built on loving submission, so nobody's dying for it. (That's where we were questioning Marston's philosophy, you know, 'Is she right, is she wrong?')

She very much has an agenda of mercy and she wants to make sure it's the best possible outcome for people, because that's what loving authority is. It's kind of scary at first. You don't know if she actually does love people that much.

Nrama: You do get the sense that she is for everybody, even for her enemies. Which is a cool thing to see in a comic book story.

I do want to touch briefly on the visuals of this book, because Harmonia is just gorgeous. Could you briefly describe working with Yanick Paquette? What is your process working together to create Harmonia?

Morrison: Well honestly, we've barely spoken.

I've met Yanick a few times and we get on. But I tend to write a big script with everything in there, send it to him, and make suggestions. Then he'll do these fabulous things that I could never have even imagined. He makes up architecture and can create the entire scene with it and can do action scenes where there are like a hundred characters under siege. It's amazing being able to work with someone who is operating on that level. It's like having the biggest budget ever for a film.

We're fortunate to get Yanick on this project. You know, he came to DC to do Wonder Woman and it's kind of occupied the last ten or more years of both our lives. So we really wanted to do it justice; we put our heart and souls into it. He thinks of this as a masterpiece and I agree, I think it's a phenomenal piece of work.

Nrama: It absolutely is. I thought it was incredible that you see the Greek influence of the art there, but it's more. It's bigger, it's kind of alien in a really cool way.

Morrison: It is. The idea is to show at least a hint of a culture that has developed along its own lines and has its own way of speaking and building and thinking.

Nrama: As the final volume of Wonder Woman: Earth One, this one really leans into the aspirational values of Wonder Woman while coming to terms with people's reach exceeding their grasps. What is your aspirational goal for Diana?

Morrison: I wanted to see Wonder Woman flower into the person that I saw in my head. You know, she's a superhero! In the same way that Superman and Batman are. I wanted to find that aspect of her that is noble and selfless and that loves us, and yet she comes from this very different culture. Her application of that culture can be quite unusual or strange to us. So what I really wanted was to just see the character that was in my head. That's absolutely this super cool young woman who smiles a lot and who's super intelligent and is a healer and is gentle.

[Earth One] is definitely the opportunity for that character to flourish. In the monthly comic books (and it's quite understandable), you have a very different Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman. They just go on refreshing themselves forever. This was my opportunity to give Diana a story where she could go through a bunch of stuff and achieve some things and also complete the circle, which she does at the end of the book.

Nrama: I remember reading an interview with Scott Snyder, he was talking about how you and he were talking about writing Batman. At one point, you said that when you're handling a character this big, you need to have an end in mind for the character and that helps form the story. Is what happens in Volume Three, the end you pictured for your Diana?

Morrison: It is absolutely. Again, that's because of that early Marston story that really does show this utopia. Because he predicted that, I wanted to take my character to a point where she was responsible for a world like that, to give her that scale and responsibility. Because like I said, in the monthly comics, you have to do the same thing mostly. But in this, I could take her to a moment of completion.

With Scott, I said that with characters like this, you also have to treat them like they are creator-owned. Like they're your own self-published comic. I figure that's the best way we can treat them, because otherwise we get caught up in these tropes and the ideas that have been growing around these characters for a long time. So yeah, treat them all as though they're your own kind of personal creation, and also give the story and ending.

Nrama: So you have to break those tropes, is that what you're saying? In the same kind of way that you broke the Joseph Campbell hero's journey?

Morrison: Yes. And I'm sure I'm still beholden to [the hero's journey], because I've grown up in a culture where that's the biggest story structure. But yeah, it was lots of fun trying to think around it and to not just do that 'Boy King Hero' story that we always read about.

The difference between that story and this one is the difference between the pyramid and the network. The pyramid is assembled by the patriarchy, there's a hierarchy to it. But the network is a metaphor for the future. It's a pattern you see in Wonder Woman a lot, with the lasso and the ropes and the nets and the spiders.

Like Wonder Woman? Make sure you've read all the best Wonder Woman stories of all time.

Grant DeArmitt is a NYC-based writer and editor who regularly contributes bylines to Newsarama. Grant is a horror aficionado, writing about the genre for Nightmare on Film Street, and has written features, reviews, and interviews for the likes of PanelxPanel and Monkeys Fighting Robots. Grant says he probably isn't a werewolf… but you can never be too careful.