Hands on with Mafia 3: mixing blood feuds and guns with some real humanity

“Never going to be over.”

If there's one line of dialogue that stays with me long after I finish my six-hour stint with a near-complete build of Mafia 3, it's this one. Many, many things resonate during my demo but this line encapsulates everything that makes the experience special.

Mafia 3’s New Bordeaux isn't built like other crime-ridden open-worlds. It's a layered, nuanced, densely packed socio-political ecosystem that's 1968 New Orleans in all but name, teeming with all the strife and tension that turned the South into such a boiling melting pot at the end of that decade. The Vietnam war rages on, wreaking damage abroad and at home. The civil rights movement is the hottest of issues, and New Bordeaux's multicultural criminal families hold an uneasy tension across the city's many, very different districts. Fundamentally, everything is connected.

Every element of this turmoil permeates, informs, and influences life at every level, current troubles mingling with and springing from historical happenings just as the current conflict reshapes the climate and pushes everything inexorably forward. Everything stacks. Everything rolls on. Nothing is ever really going to be over.

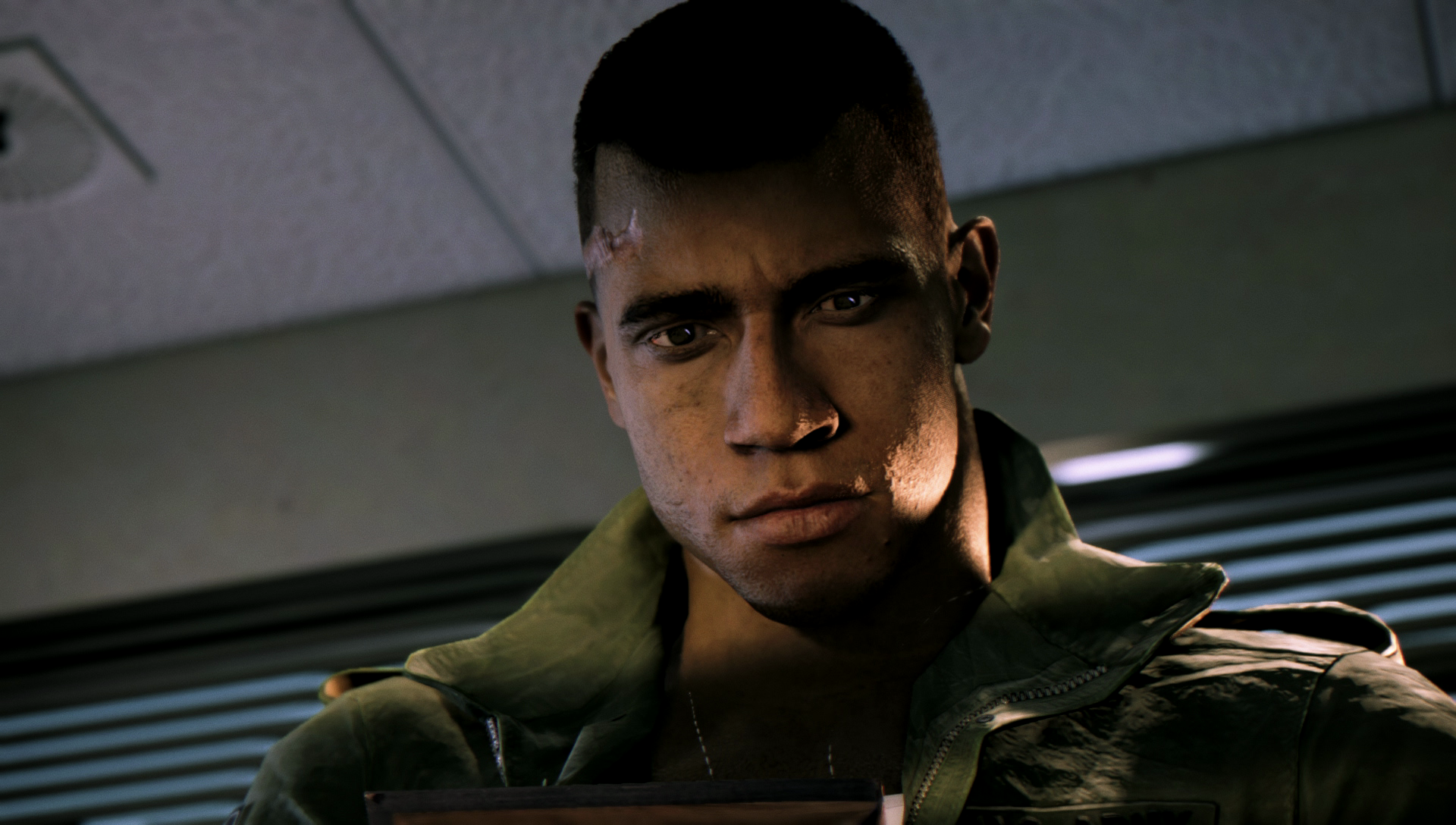

If you need a direct personification of that fact, then you'll find it in protagonist Lincoln Clay, a mixed-race Vietnam vet of uncertain parentage, returning from war to his adopted family in the local black mafia. He seems in good shape, but he has changed in his time away. And when a brutal and dramatic betrayal by the Italian mob leaves him once again an orphan, everything he's been and is, everything in New Bordeaux's past and present, is going to direct his path.

Mafia 3, unlike other open-world crime sims, isn't interested in broad-strokes, cartoon carnage and goofy distractions. Mafia 3 is interested in portraying a real world - hell, the real world - with all of its warts and complexity. This becomes immediately obvious in the first real mission, in which Lincoln works with the as-yet-allied Italians to execute a heist on a Federal cash reserve. On the way in, both men undercover as security guards, his white partner explains that he might have to feign racism when they arrive, in order to fit in, and apologises in advance.

This does indeed happen, but the scene plays out with a great deal more interesting, tonal texture than you might imagine. Where Mafia 3 could have simply dropped a few n-bombs in order to bluntly - and clumsily - indicate that certain characters are bad, the conversation, for all of the unpleasantness of the attitudes on display, is more nuanced. There's little sense of deliberate malice or conscious abuse, but rather a believable, socially-approved lack of self awareness. Lincoln isn't attacked, but simply spoken about as if he isn't there, patronised and dehumanised via the matter-of-fact normality of inequality rather than targeted assault. And he puts up with it, because he has things to do. He's long been used to this treatment, and has bigger matters to deal with.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Mafia 3 isn't content to simply show The Bad Thing for a cheap, dramatic hit. It wants to explain, be that by layered expression or explicit discussion. When Lincoln later carries out a hit against the rival Haitian gang, the mission is pre-empted by the game's striking framing device, which uses ‘declassified’ footage of a fictional government hearing and various talking-head interviews to present Lincoln's story as historical documentary.

In this case, we're told the troubled history of the Haitian mob, an unfortunate by-product of mass displacement caused by political traumas in their homeland. They're still the bad guys, and they still need to be dealt with, but they're really only the bad guys from Lincoln's perspective. They're violent criminals, but so is he, and both sides are just looking after the interests of their own family, forced into this situation by external circumstances that have existed decades longer than the current conflict.

Not that Mafia 3 eschews excitement for dry social history. Its discourse is unmistakable, but so deftly threaded through the fabric of its world, by way of explicit story events, ambient dialogue, and the dynamic responses of New Bordeaux itself, that it doesn't intrude on the interactive experience, but rather elevates it.

The latter treatment can be particularly powerful, with different regions of the city reacting to Lincoln in very different ways. Boost a car in the poorer, predominantly black neighbourhood of the Hollow, and it's likely no-one will stop you. But simply sprint down the street with a weapon visible in the affluent, very white suburb of Frisco Fields, and you might very well find an excess of police forces bearing down upon you in no time. It's a worked example of Mafia 3’s historical accuracy expressed to the player through gameplay, evoking an immersion in Lincoln's overall situation far beyond the specifics of any particular mission objective.

And when Mafia 3’s action kicks off, it kicks off hard. Driving around New Bordeaux - even just in between missions - is a consistent pleasure, vehicle handling exhibiting a finely pitched balance of weighty heft and exciting, arcade immediacy as you take in an evocative landscape of sprawling Southern splendour and dynamic weather systems as spectacular they are oppressive. But when the other kind of heat is on, Mafia's predilection for ‘Hollywood action driving’ really makes itself apparent.

With New Orleans’ decidedly flat terrain modified take in a great deal more jumps and elevation than you'll find in the real Louisiana city, Mafia 3’s chases often take on a giddy, Blues Brothers-like kinetic energy. Cars soar like birds and crash down like rhinoceroses, skidding and slamming to create an effect just the right side of slapstick, just close enough to the edge of control. As for the on-foot action, while shooting doesn't currently feel like it has quite the same satisfying snap it did when I played the game back in April - hopefully that will be tuned up before release, though the current gun-feel certainly isn't a deal-breaker - the combat structure within which it exists makes up for any slight shortfalls in the weapon handling.

Pulling a trigger is only one of many options in Mafia 3. Getting to the point where you might want to pull a trigger is simply a possibility. Even in that largely linear early mission against the Haitians, things feel far more Splinter Cell than Gears of War. Or at least they can if that's what you want. Stalking through the mob base to assassinate its leader, I'm rapidly struck by the nonlinearity of it all. This is an A-to-B mission, but a great many other letters have been squeezed in between.

The direct route is totally viable, but so are many hidden paths through side-buildings. Secluded ladders deliver rooftop gantries, whose toll is a couple of well-timed throat-stabs and a deftly-hidden body or two rather than a furious hail of bullets. And throughout, Mafia 3’s enemy AI feels very well pitched toward facilitating whatever I want to do, without ever giving me an easy ride.

In open firefights, it remains focused and surprisingly aggressive, but it's easily enough shaken that I can actually use the more incendiary chaos I cause to de-escalate rather than further inflame, sprinting away from the confusion to find a secluded spot in which to lay low. Survive a tense but thankfully not over-long search, and it's entirely possible to reset the enemy alertness level, even from a state of all-out carnage, in order to regroup and rethink. Games that try to blend action and stealth often have trouble reconciling the transition between the two, but Mafia 3 seems to have no such problems.

But if the various states of Mafia 3’s core action meld and merge with dynamically satisfying ease, it's the connectedness of the game's wider, meta systems that really fleshes out the sense of New Bordeaux as real place. While the map is entirely full of objectives and options, every one is tied back into Lincoln's overall goal, each hit made chipping away at the fortunes of one of the rival gangs’ rackets, edging Lincoln closer and closer to a decidedly hostile take-over.

And with freedom of choice over which sub-missions to take, and further freedom over how to tackle each one - the organic nature of the Haitian strike’s environmental design is just a tease of what's to come when sniper rifles, noise-making distraction grenades, intel-gathering phone-taps, friendly hired goons, and a wide-open city layout come into play - the idea of ‘branching action’ feels like a distinct understatement. Just like New Bordeaux's social and political tensions, its troubled past and heated present, everything flows and everything is connected. Mafia 3 feels like a game whose structure presents a deliberate analogue for its narrative conceits, one where both feed into the same goal of creating nuanced layers of believable resonance throughout its world.

All of which brings us back to Lincoln, at the end of the game's first act, resolving to avenge his fallen family as he shaves his civilian haircut down to military neatness using his Vietnam combat knife. Because while that war might be in his past, the warrior it made him is very much his present and future. A notorious period of international political action is having a very real effect on the streets of New Bordeaux, and one war is about to beget another. And knowing everything that's led to this point, while the situation certainly isn't glorified, it is rationalised and entirely understandable. Because Mafia 3 likes to explain things. It likes you to understand why bad things happen. And it knows that some things, really, are just never going to be over.