Has the most powerful console of a generation ever actually won?

Console power. Since the misty dawn of the early ‘90s, when all was unicorns, new-age synth, and wizards, it has been the first and most furious topic of conversation surrounding the announcement of each and every new games machine spat up by the earth. ‘How much faster will it be? How much shinier and more numerous its pictures? By what percentage will it allow me to chisel down my best friend’s self-esteem by denigrating his personal identity based upon his recent hardware purchase choices?’

But is any of this important beyond the ephemeral ebb and flow of transient ego-massage? Should a console turn out to be as powerful as a big horse and twice as beautiful, does such equine splendour even matter when it comes to cold, hard success? With the whole stinking hot tussle kicking up again thanks to the imminent full reveal of Microsoft’s souped-up Xbox Scorpio – due to go nose to angry nose with Sony’s counterpoint mid-gen upgrade, the PlayStation 4 Pro, later this year – I thought it was time to step away from the impassioned spewing of stats and take a historical look back at horsepower throughout the ages, and just how important a role it has actually played in settling each phase of the console war. Starting with…

The 8-bit generation

The winner was… The NES. Going up against the Sega Master System and Atari 7800, Nintendo’s 8-bit machine clearly dominated the industry’s inaugural reboot generation following the great games console crash. Selling 62 million units worldwide, vs. the Master System’s second place 18 million and the 7800’s single million, watching the success of the NES was like witnessing Godzilla fighting a clown made of mashed potato.

But did the most powerful console win? Not really. While an entirely capable console for the period, the NES was arguably a tad less powerful than Sega’s machine. Obviously the whole issue gets a bit muddy in these early generations, given the scope for game-by-game hardware boosts afforded by the cartridge technology of the time, but although there’s still some debate, the Master System is generally acknowledged as having more raw power out of the box. Rather, Nintendo won by locking down the US market with an early release and a strong first-party line-up. And just as crucially, by holding third-party developers to exclusivity for two years. With an early, dominant market share in Japan and the US, that created self-perpetuating momentum that the Master System, for all its strength in Europe, just could not catch.

The 16-bit generation

The winner was… The Super NES. Scoring 49 million sales against the 34 million achieved by Sega’s Mega Drive / Genesis - with outlying competition from the PC Engine / TurboGrafx-16 and Neo Geo AES in third and fourth place respectively - the early ‘90s were another convincing win for Nintendo, albeit also a period that saw Sega make up considerable ground from the generation previous.

But did the most powerful console win? Nope. The debate regarding overall power is again – at least between the two market leaders – a messy one, the SNES powered by a slower processor but sporting better overall graphics tech, as well as sound that flattened that of the Genesis like a recently dropped moon. As the generation went on, both consoles upgraded themselves. The Sega machine opted for an endlessly stacking monolith of CD-drives and 3D accelerators, while the SNES went for the simpler, but far less confusing in-cartridge Super FX chip, which facilitated the likes of Starfox and Doom. Rare’s experiments in the area of pre-rendered sprites managed to give the impression of much greater power too, via the gorgeous likes of Donkey Kong Country.

However, both machines paled next to the Neo Geo AES, which is the textbook historical example of raw horsepower being not simply ‘no guarantee’, but also sometimes ‘A total goddamn hindrance, you fools, why did you ever think anyone would pay for this?’ Essentially an attempt to bring the full-fat, SNK arcade experience home, the AES was undoubtedly a majestically powerful machine that no rival could hope to compare with on a pure hardware level. But being eyebrow-raisingly expensive at launch (the 1991 equivalent of $1143 with a game and spare controller, around $700 without), and with several of its more notable fighting game ports later available in less impressive but still entirely decent SNES versions, the Neo Geo was a classic case of prioritising ‘can’ over ‘should’. It clearly delivered the best technical performance but, positioned as a luxury console, had little care for how many people wanted, needed, or could afford it. In the end it sold roughly 20% of the Super NES’ numbers.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

The 32 / 64-bit generation

The winner was… The PlayStation. Obviously. Selling 100 million, Sony’s debut console – notoriously the product of a soured SNES CD-drive deal with Nintendo – tripled the sales of the Nintendo 64, its closest rival by some distance. As for that third place? It went to Sega’s Saturn, which in turn only did around 30% of the N64’s numbers, the space-based sad-seller moving 10 million units compared to Nintendo’s 33 million.

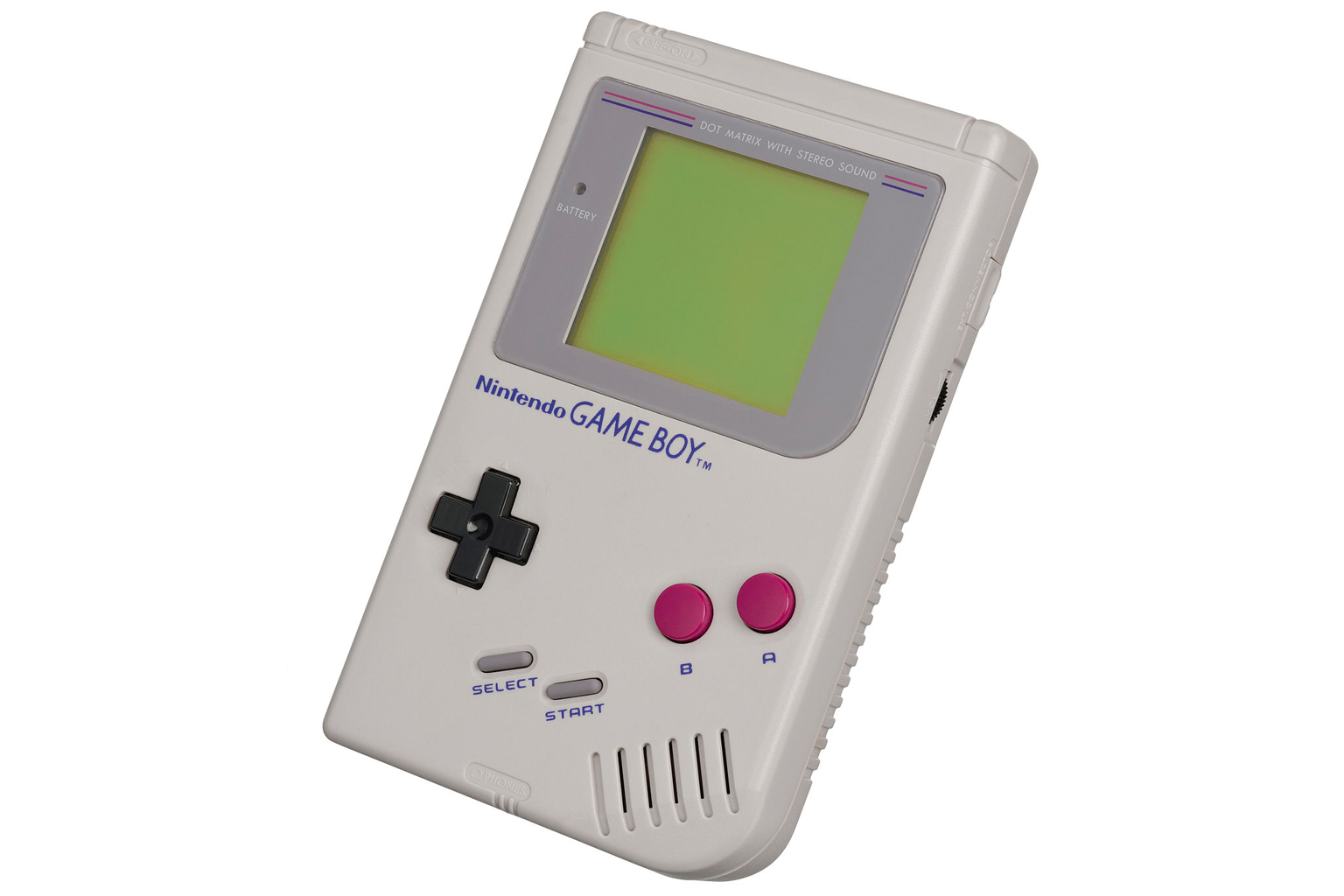

Handheld gaming has typified the 'power doesn't matter' rule ever since Nintendo's monochrome Game Boy prioritised battery life and portable-friendly game design to see off the Game Gear's more AAA approach. The same pattern has echoed ever since, with the DS beating the PSP and the 3DS defeating the Vita. The idea of a 'home console in your pocket' has just never really worked out.

But did the most powerful console win? Nope and nope again. Admittedly, the N64 somewhat scuppered itself in the power stakes by sticking to the cartridge format for game storage rather than embracing the bigger capacity of CDs like everyone else did, but in all other respects, the Nintendo 64 was more powerful than the good old PS1. With a significantly faster CPU, a beast of a graphics processor, double the RAM by default – and the facility to double it again with the Expansion Pak later down the line – and nearly twice the polygon-shifting capacity, the N64 is, on paper, the underrated monster of its generation. Heck, for all its limitations and lack of support, the Saturn was technically capable of outperforming the PlayStation in some areas too.

So how did the PlayStation win? Simply, Sony targeted an audience beyond the traditional gaming market. It went all-out to make video games mature and cool rather than simply fun, establishing PlayStation gaming as a lifestyle statement as much as a pastime. Thus, it absolutely romped home, managing not only to steal a big chunk of the existing market share, but also to carve out a whole new one for itself. Bravery and smart marketing, from a company entering the industry with a fresh mindset and no preconceptions. That’s what made the PlayStation a success. Branding, newness and the cool-factor. For the mass market audience, there are factors way more important than frame-rates and screen resolutions.

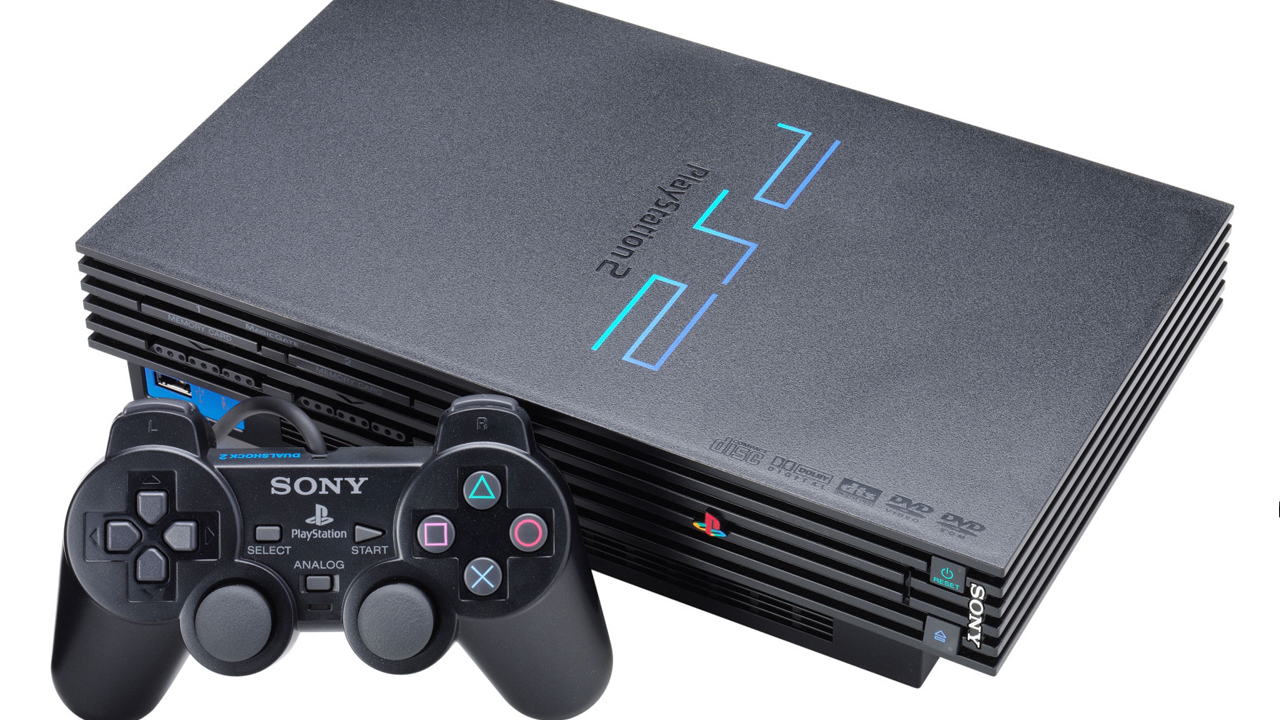

The 128-bit generation

The winner was… The PlayStation 2, by an even bigger margin than its predecessor. Running away with 155 million sales, it flattened Microsoft’s newcomer Xbox (24 million) and Nintendo’s GameCube (22 million), and buried Sega’s Dreamcast (9 million) to almost turn its chapter of the console war into a one-horse race. Never has a console generation been so belligerently one-sided.

But did the most powerful console win? Not in the slightest. In fact, you can roughly consider this generation the scaled-up sequel-cum-remake of the one before it. Sony had, overall, the weakest console. Nintendo had a more powerful machine, nerfed by an insistence on a smaller proprietary disc format over the industry-standard DVDs (and now, lessening third-party support). And in technical terms, the new Xbox stomped them both, delivering a monstrously powerful home console with the soul of a PC, near-enough doubling the PS2’s stats in a deliberate, defining, statement of intent. But it didn’t matter.

Sony’s smartly strategised, still-energised market position from the previous generation held strong. The PlayStation brand maintained the cool-factor that had made it such a major player and, via an increasingly eclectic first and third-party library, expanded its reach to pretty much everyone, exploding the size of the global gaming audience at the same time. A huge install-base brought about a vast and varied development ecosystem, and in turn, more variety in games sold even more consoles. Thus, ‘PlayStation’ became a byword for ‘video games’ in much the same way that ‘Nintendo’ had been a few generations earlier. At this point, Sony’s pure momentum seemed unstoppable. But then we got…

The HD generation

The winner was… Ironically, given the name I’ve bestowed upon this generation (or perhaps fittingly, given the ongoing subtext of this feature), the Wii. By 20 million. Both the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 eventually (relatively) caught up with Nintendo’s runaway success, selling 80 million and 84 million respectively as they fought their own, hotly contested back-and-forth race. But the fact remains than in terms of pure console sales (and brand awareness), Nintendo came out of nowhere to wreck the competition this time around, to the tune of 100 million consoles sold.

But did the most powerful console win? AHAHAHAHHAHAHAHAHHAHA! No. The Wii had the comparative power of a shoebox stuffed with magnets when it launched. Sporting last-gen grunt, the most standard of available definitions, and a storage capacity so small that tardigrades would knock it through to a patio extension, it could easily be argued that the Wii had no right to do well at all, were we still assuming at this point (in some frenzied defiance of reason) that horsepower actually mattered. But the Wii had something more going on.

In motion-control, it had a new innovation/gimmick that genuinely reignited excitement about games in a way that the sparkly – but crushingly reliable – generational increase in processing power no longer could. Whether you were a long-time, mainstream gamer, a hardcore Nintendo stalwart resigned to third-place non-glory, or simply someone’s gran, the Wii looked exciting and fun. And for a while, it really was. Nintendo knew this. Nintendo planned for this. And while engaging software support ultimately proved patchy, and third-party publishers made nary a bean, in terms of putting consoles in people’s homes and making a staggering comeback in regards both profits and profile, the little white waggle-box absolutely killed it.

Contrast that with the PlayStation 3, which was initially ‘sold’ off the back of supposedly incredibly powerful proprietary processing technology, with a high price to go along with it – and comparatively tanked for years as a direct result – and you have the strongest case since the Neo Geo for Microsoft needing to be very, very careful indeed with how it handles the Scorpio.