I’ve been a big fan of city builders in my teenage years, when I used to plow hours into urban planning in Sim City 2000, and ignored combat in Age of Empires II and Command and Conquer: Tiberian Sun to create perfect little settlements with logically laid out buildings.

Being younger, I was more willing to bend these games to my will, imbuing the cities and bases with little stories, only letting harvesters and villagers out of certain gates and creating fancy fortifications, the likes of which you’d often click units through in story missions.

Our guide to the best city building games of all time will have you hoovering up tax collections in no time

As I’ve got older I have understood that this was because cities are filled with decisions that are imbued with narrative and opportunities for storytelling. Creating buildings, districts, traffic networks: it all takes time, and represents years of decisions, and often centuries of expansion. Whilst there’s joy in plonking down buildings in pretty patterns in games, it always feels better when there is a reason for the placement: a story that makes the city tick.

City builders have become a fairly popular genre in recent years, but they’ve rarely capitalized on the narrative aspect. Per Aspera is a game that gives players a chance to both enjoy building sprawling settlements, whilst also contemplating the impact each of their decisions has within a larger narrative framework.

The Red Planet

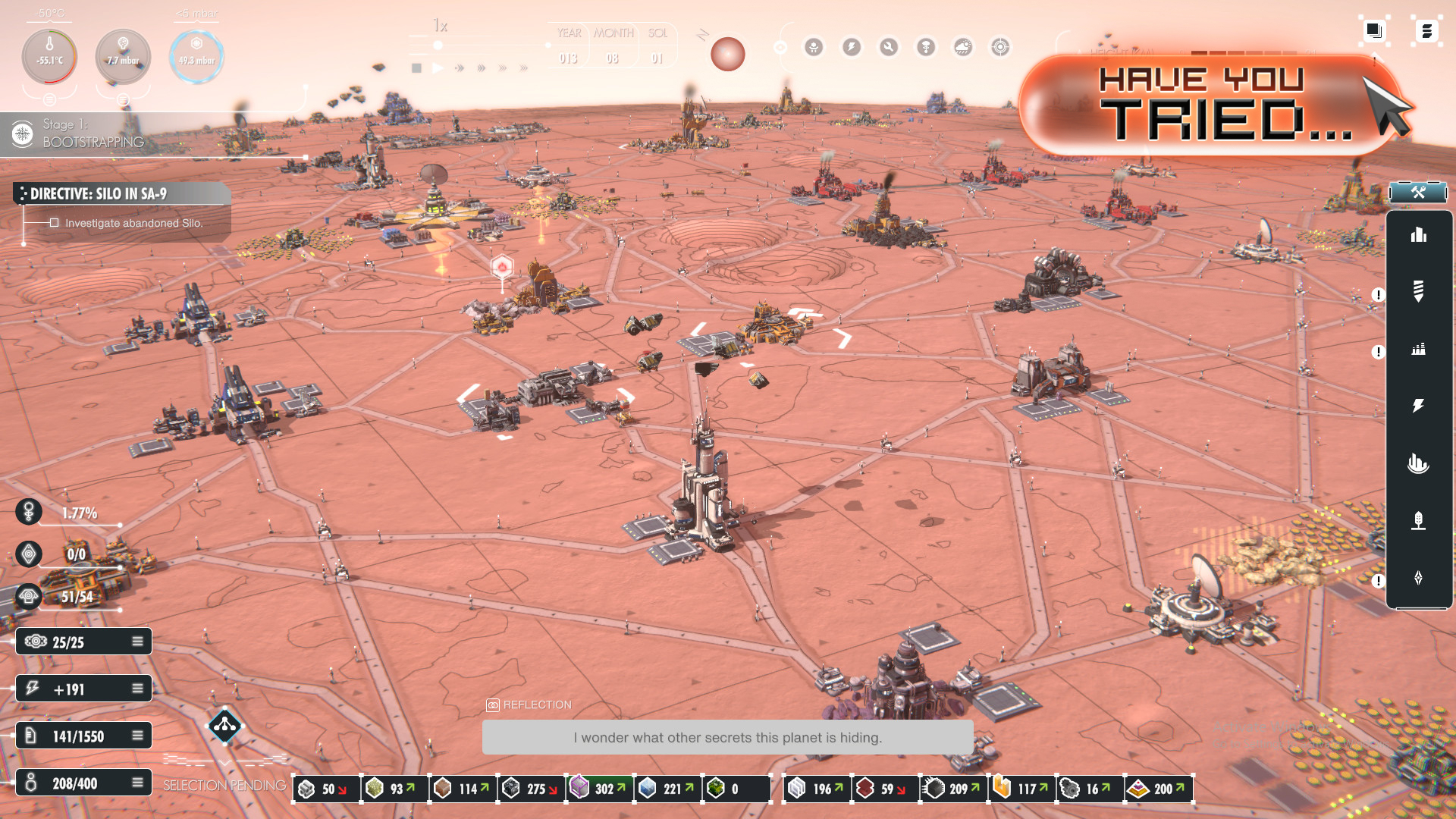

Set on Mars, you play the part of AMI, a super-advanced AI tasked with preparing Mars for colonisations, and later terraforming the planet as part of humanity’s expansion to the stars. During play, you’ll build your Mars base with the help of a network of drones.

Place a building and your AI will create connective roads - theorizing a multitude of options before placing the most optimal one. You’ll mine aluminum, coal, silicon, and a variety of other materials from the planet to expand over the red planet like some sort of benevolent metal fungus.

Whilst doing this, you’ll also be fielding calls from a cast of characters including your designer and curator Doctor Foster (voiced by Troy Baker) and colonist leader Elya Valentine (Lynsey Murrell) who will keep tabs on your progress, and task you to answer questions about your processes.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

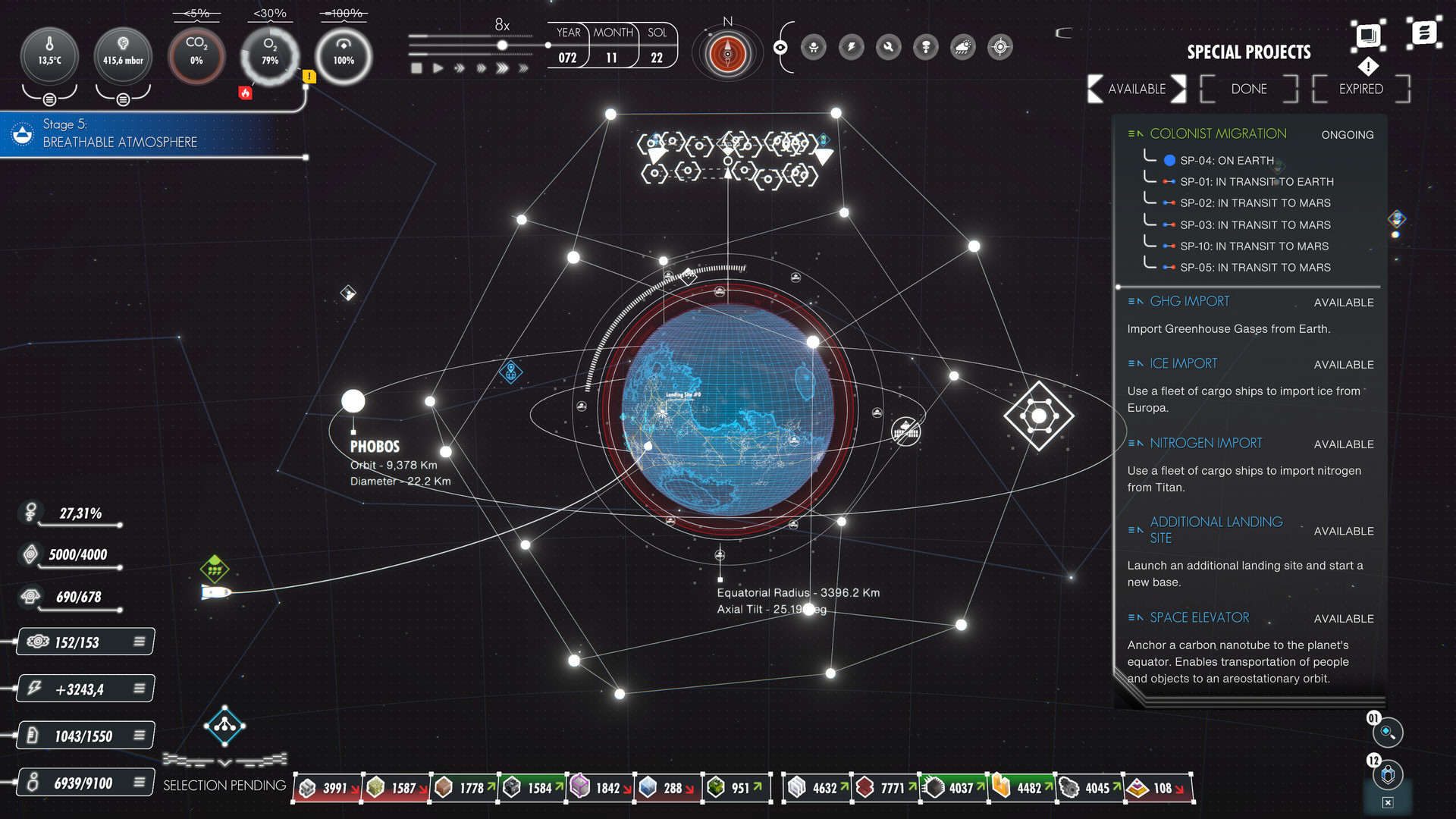

Is what you are doing best for the planet? Best for the colonists? What is the correct way to terraform a planet: should you bask in the glory of the power of your accomplishment, or should you attempt to retain as much of Mars’s natural wonder as possible?

Per Aspera bucks the trend of building sims in a similar fashion to Frostpunk, in that it not only gives you a rhyme and a reason for building but also challenges you to think about what you’re doing. These choices resonate throughout the game, eventually leading you down specific story paths that have AMI interrogate her own identity as an AI, and into territory best left unspoiled.

Meeting the makers

Because of its unique angle, I reached out to developers Tlön Industries and had a brief chat with Javier Otaegui, game director and one of the studio’s three co-founders, to dig a little deeper into the motivations and inspirations behind such an ambitious melding of mechanical process and narrative. Otaegui tells me that he had always loved strategy games, but that over the years he had also been drawn to ambitious narrative games over the years, such as Firewatch, 80 Days, Event [0], and Heavens Vault.

Despite a long list of heavily narrative games, Otaegui tells me that the main mechanical inspiration of the game was old PC favorite Settlers. They believe its mechanical focus on supply-chain management was a fascinating core conceit, and when thinking about games that could be made from that mechanic, they found an AI narrative suited it best.

Explaining more, Otaegui says "I’ve always found the mechanicist game design theories lacking in the sense that stories cannot just be a layer of frosting for the underlying mechanics - there must be something more. Per Aspera is an experiment." As a game, Otaegui considers Per Aspera a demonstration of the idea that "narrative and gameplay do not need to be tradeoffs, they can work together to create an amazing experience. That is what Per Aspera is all about, and that’s why we thought it needed to be developed."

Amongst the influences for the game, Tlon Industries explored a lot of influences beyond games, such as scientific books like The Case for Mars by Robert Zubrin, as well as films and TV shows such as The Martian, The Expanse, Moon, and Westworld. Many of these would be anticipated as par for the course for such a narrative, but exploring Julian Jaynes’ Bicameral Mind Theory, which was influential for Westworld, via the manner of play certainly hits differently.

As the crux of the theory is rooted in the idea that the cognitive functions are essentially divided between two halves of the brain, one "speaking" and one "listening" and as the player you form part of the equation, lending more credence to the idea of AMI learning about themselves, and operating as a super-advanced AI.

Experimental features

Otaegui posits that Per Aspera was an experiment, and as such, it was quite the challenge to pull off. Specifically, they wanted to have the narrative and the mechanical aspects working in tandem, rather than inserting narrative moments in-between missions as is often common. Despite many choices in the game feeling like they have an impact, frequently the game gently nudges players rather than shoving them.

Due to the game’s long playtime and simulation aspect - Mars and its atmosphere are simulated wholesale - Otaegui explains that "it was practically impossible to do a completely open-narrative with thousands of branches and options as we are still an indie studio".

Otaegui describes that the narrative beats are organized as a "vine" which "defines certain specific mandatory plot points, and in the middle, several optional missions and different endings are enabled based on your relationships with each character."

The ending of the game can still be one of a few different outcomes, but Tlon Industries wanted players to explore both the simulation and Mars itself and as such the story is reactive to this exploration. If you decide you need to build a certain way to get a specific material, the story may well push back as you discover new areas of the planet.

As Per Aspera was essentially an experiment into a fusion of genres, Otaegui and his colleagues were extremely interested in what players would make on it, saying, " We did not want to alienate pure-strategy players which may not care for the story or combat elements but also, we wanted to be able to create a game that was not just micro-management focused to still be attractive to players that enjoy storytelling."

It certainly caught me off-guard - I knew the narrative would be part of the game from its description, but it’s hard to articulate quite how it coiled its way around me as I played. It is by turns thought-provoking, creepy, and impactful, and really made me think about my decisions. Otaegui hastens to add that there is a Sandbox mode for players not interested in the narrative, but that in the end, they were "happy with the general player reaction to our main hypothesis, that is that gameplay and narrative do not need to be a tradeoff."

Whilst many city-builders continue to eschew narrative due to the complexity it adds to an already complex genre, Per Aspera is worth the time to investigate. It’s one of gaming’s hidden gems, a SciFi story that manages to capture the feeling of exploring a potential future, and it does so in a way that manages to explore a potential future for city building games at the same time.

Per Aspera is out now on PC.