Why you can trust GamesRadar+

CLOUD PLEASERS

He’s said it before, as he readily admits, but this time looks like it’s finally true: at age 73 Hayao Miyazaki, rated by many as the world’s greatest living animator, is stepping down. So this Blu-ray collection of all 11 of his feature films comes as a bittersweet tribute to the man who inspired Pixar’s John Lasseter and once had a samurai sword sent to Harvey Weinstein – (who was planning to release Princess Mononoke (1997) in the States) – with the terse message “No cuts”.

What other animator has inspired such a sense of wonder and delight in the natural world? Consider the cavalcade of weird, wonderful, squirmy and tentacled sea-creatures that wriggle and plop across the screen at the start of his marine fable Ponyo (2008), or the enchanted forest-world revealed to the wide eyes of two small girls in My Neighbour Totoro (1988). Consider, above all, Miyazaki’s clouds. Several of his films begin with a cloudscape, and surely no animator has ever depicted clouds – thunderous or fluffy, dense or misty – with more loving precision.

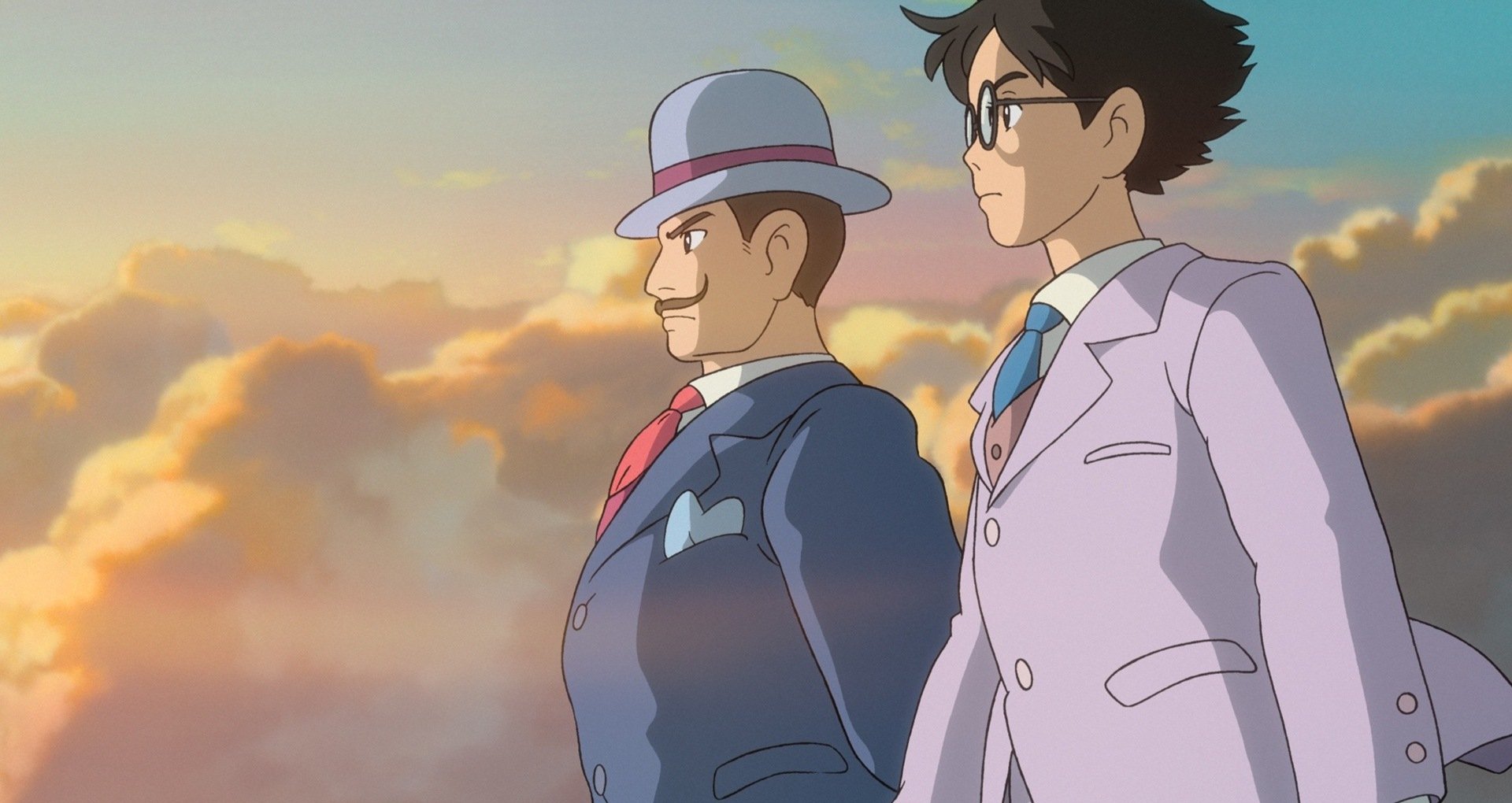

Of course, Miyazaki has always reached for the sky – literally as well as figuratively. The son of an aircraft designer, he’s been captivated by flight throughout his career. Bizarre flying machines, always rendered in intricate detail, feature strongly in many of his movies, from post-apocalyptic fantasy adventure Nausicaä Of The Valley Of The Wind (1984) to historical bio The Wind Rises (2013). Even when they’re not directly concerned with flying, his films soar. There’s a lightness and an exhilarating sweep to them that make most other animations, however skilled, feel positively earthbound by comparison.

Along with Miyazaki’s love of nature goes a strong ecological conscience that colours almost all his films. (Nausicaä carries the imprimatur of the World Wildlife Fund.) They can be lighthearted – take Totoro, or Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) – but there are often dark undertones to his work, an awareness of human cruelty and destructiveness. It’s a side that comes out strongly in his swan-song, The Wind Rises, where idealistic aircraft designer Jiro is forced to realise the lethal ends his inventions will be used for. Of the 11 films in this boxset the weakest, not surprisingly, is the earliest, The Castle Of Cagliostro (1979). A spin-off from a TV series (for which Miyazaki directed some of the episodes), it feels frenetic and cartoonish by his later standards, though it does kick off with an impressively dynamic car chase.

From this to his next film Nausicaä is a quantum leap in every direction. Generally reckoned the first Ghibli movie (though the studio was only officially initiated just after its release), it introduces two classic Miyazaki elements: flying, and a spirited young heroine. This is a filmmaker who’s always been in touch with his feminine side.

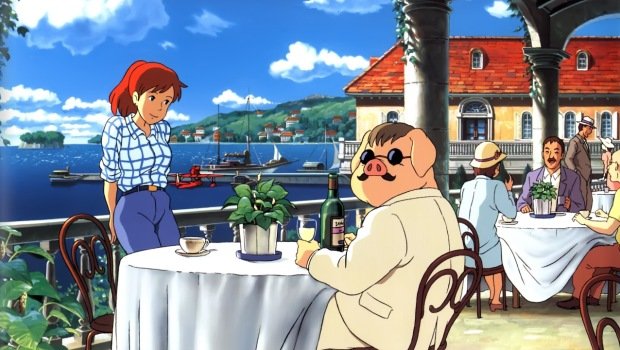

From here on in it’s a strike rate that few in any genre could equal. Riveting moments abound: the nightmare opening of Princess Mononoke when a horrendous monster, part-boar, part-spider, covered in huge writhing worms, attacks a small village; the virtuoso attack on the pirate-plane in Italian-air-ace saga Porco Rosso (1992); in Totoro, the sudden magical apparition out of the rain of the manically grinning cat-bus. But Miyazaki’s films, as Lasseter has noted, also “celebrate the quiet moments”; even in Cagliostro it’s not all slam-bang action, and in the later films he’s often content to watch his characters just being, reflecting or tentatively reaching out to each other, or to show us the beauty of the wind ruffling the grass.

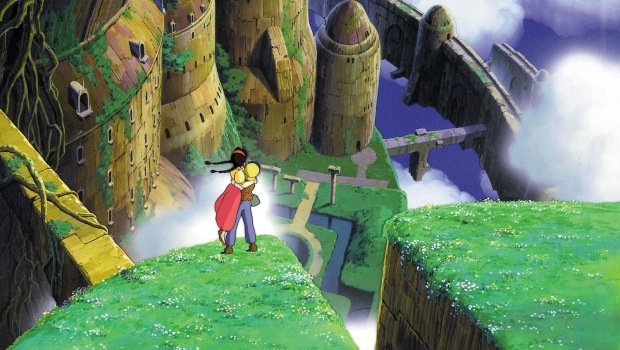

There are riches and complexities in his films to invite repeated viewings. Influences from western literature are stirred into the mix: Jonathan Swift is referenced in Laputa: Castle In The Sky (1985), Thomas Mann in The Wind Rises, and Spirited Away (2001), Miyazaki’s Oscar-winning international breakthrough movie, reworks themes from Alice in Wonderland to unsettling effect. Uniquely among his films – since he normally creates his own stories – Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) is adapted from a novel, a fantasy by English author Diana Wynne Jones. It’s let down a little by its unfocused plot, but even second-rank Miyazaki is streets ahead of the rest of the field. And the castle itself is a gloriously ramshackle, intricate creation, lurching erratically along on hen’s legs like something out of Russian mythology.

So, a complete run of the great Miyazaki’s feature-length films, in impeccable, gorgeous Blu-ray transfers – what’s not to like? Well, just one thing: the woeful dearth of extras. Each film comes on a vanilla disc, utterly unaccompanied; a 12th ‘bonus’ disc contains just the 95-minute press conference at which Miyazaki announced his retirement from filmmaking. It’s initially amusing to watch HM, with urbane charm, stonewalling over-excited questions from the press, but after half-an-hour the interest palls. And that’s it. No shortage of items that could easily have been added, filling out the picture: the eight or nine shorts that Miyazaki’s directed in the last two decades, some of his early TV work, even at a pinch the storyboards and trailers included on Studiocanal’s individual releases. But no. For a boxset retailing at near-on £200, ‘ungenerous’ scarcely covers it.

Extras

- Press conference

- Booklet

More info

| Blu-ray release | 8 December 2014 |

| Director | Hayao Miyazaki |

| Films | "The Castle of Cagliostro","Nausica of the Valley of the Wind" |

| Laputa | "Castle in the Sky","My Neighbor Totoro","Kiki's Delivery Service","Porco Rosso","Princess Mononoke","Spirited Away","Howl's Moving Castle","Ponyo","The Wind Rises" |