How Housemarque’s Nex Machina is rocketing arcade shooters back to the top on PS4

Eugene Jarvis and Harry Krueger know a thing or two about twin-stick shooters. The former’s an industry legend, the man behind the arcade games Defender and Robotron: 2084. The latter’s proven his mastery of the genre on PS4, heading up programming on Resogun.

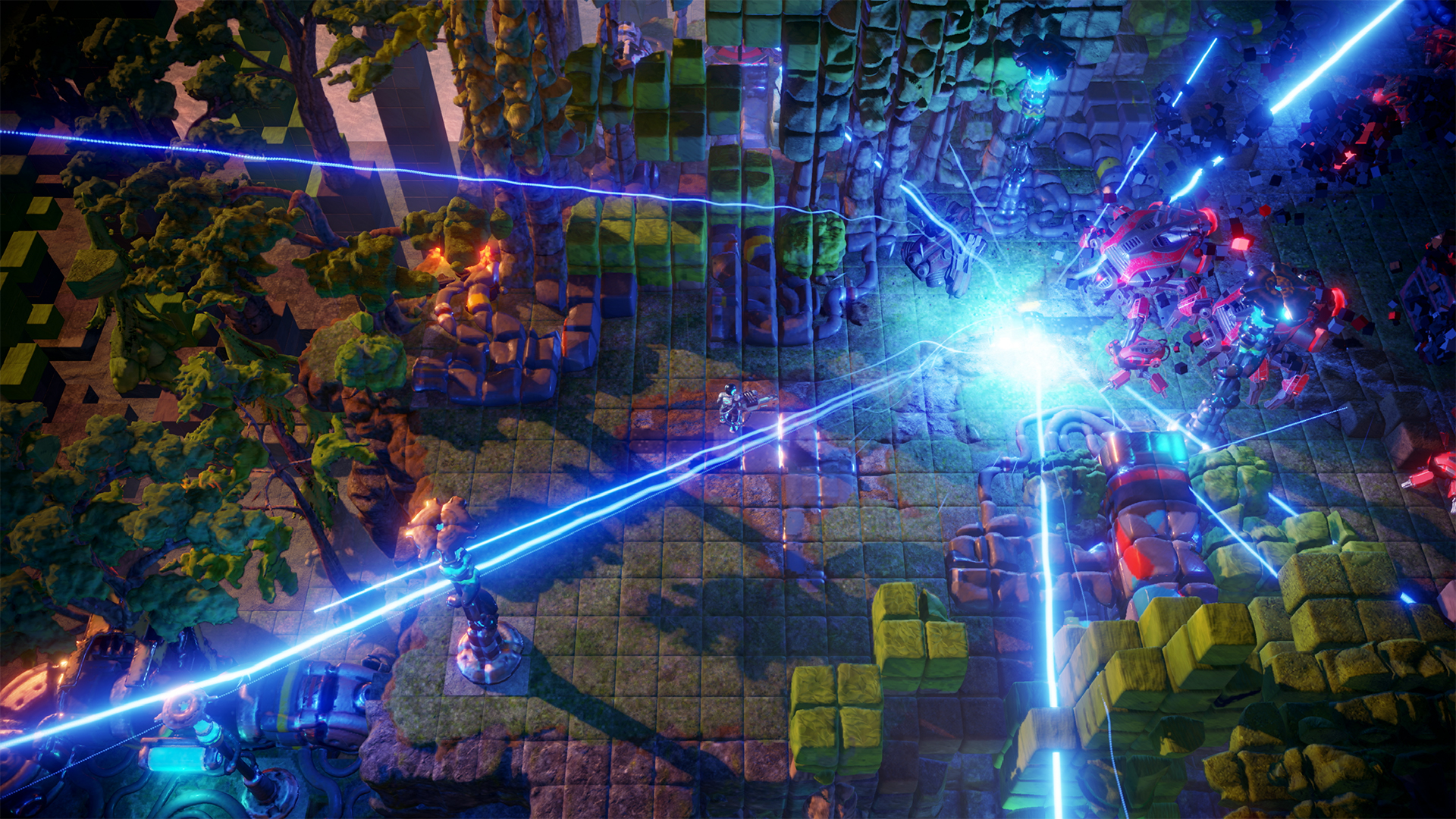

You couldn’t pick a more perfect pair to develop Nex Machina – an unapologetically brutal and beautiful ode to arcade joy. Resogun’s twin-stick, top-down, voxel-drenched follow-up is set to be stunning, from what we’ve played so far. We caught up with Jarvis (creative consultant) and Krueger (game director) to find out the secrets behind creating a challenge no PlayStation fan can resist...

OPM: How long have you been working on Nex Machina? What’s it like to finally see people playing your new game?

Harry Krueger: We started working on this when we completed Resogun, so it’s been about two years now. It’s really satisfying. It feels like all of the hard work we’ve put in with the team and Eugene over the last couple of years, it all just culminates in this one moment. And this justifies all of our hard efforts.

Eugene Jarvis: It was a kind of a long voyage, and we did a lot of experimental things. A lot of things didn’t work out or they led to another thing that was better. So it was a little frustrating for quite some time – we just couldn’t get the game to mould to the vision we had. It had fun elements and certain things were interesting, but it was just not advanced enough. The last few months have been this huge breakthrough, it’s from working day and night.

OPM: What was your vision for the game?

HK: Making a spiritual successor to Robotron was one of the original drives. At Housemarque we have our own kind of style – arcade-style gameplay. I think you can definitely recognise a bit of Resogun’s DNA in Nex Machina as well. But the goal has been to create this intense, fast-paced, pure kind of arcade experience.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

EJ: Yeah, and I think the purity of the old classic arcade games with the 2D presentation, the single screen was – in this format, the twin-stick shooter – the sense of confinement. Where you’re just cornered, you’re surrounded, you’re fighting your way out, you’re running away, and shooting as you’re running toward them. Just complete panic, all this adrenaline, emotion, and crazy stuff. It’s always been that problem, because then you go to this 3D world and then the world’s too big, you just start running around in this huge world.

HK: You need constraints.

EJ: Yeah. You have cool immersive 3D graphics, and so how can we take the confinement of 2D but then have the amazing 3D graphics? And I think we have finally figured something out. This voxel thing – in the original Robotron it was just pixels, and now the voxels have gone into 3D, and it’s almost Minecrafty.

OPM: How do you make a game that’s so demanding feel fun? Does the satisfaction of seeing those voxels explode help?

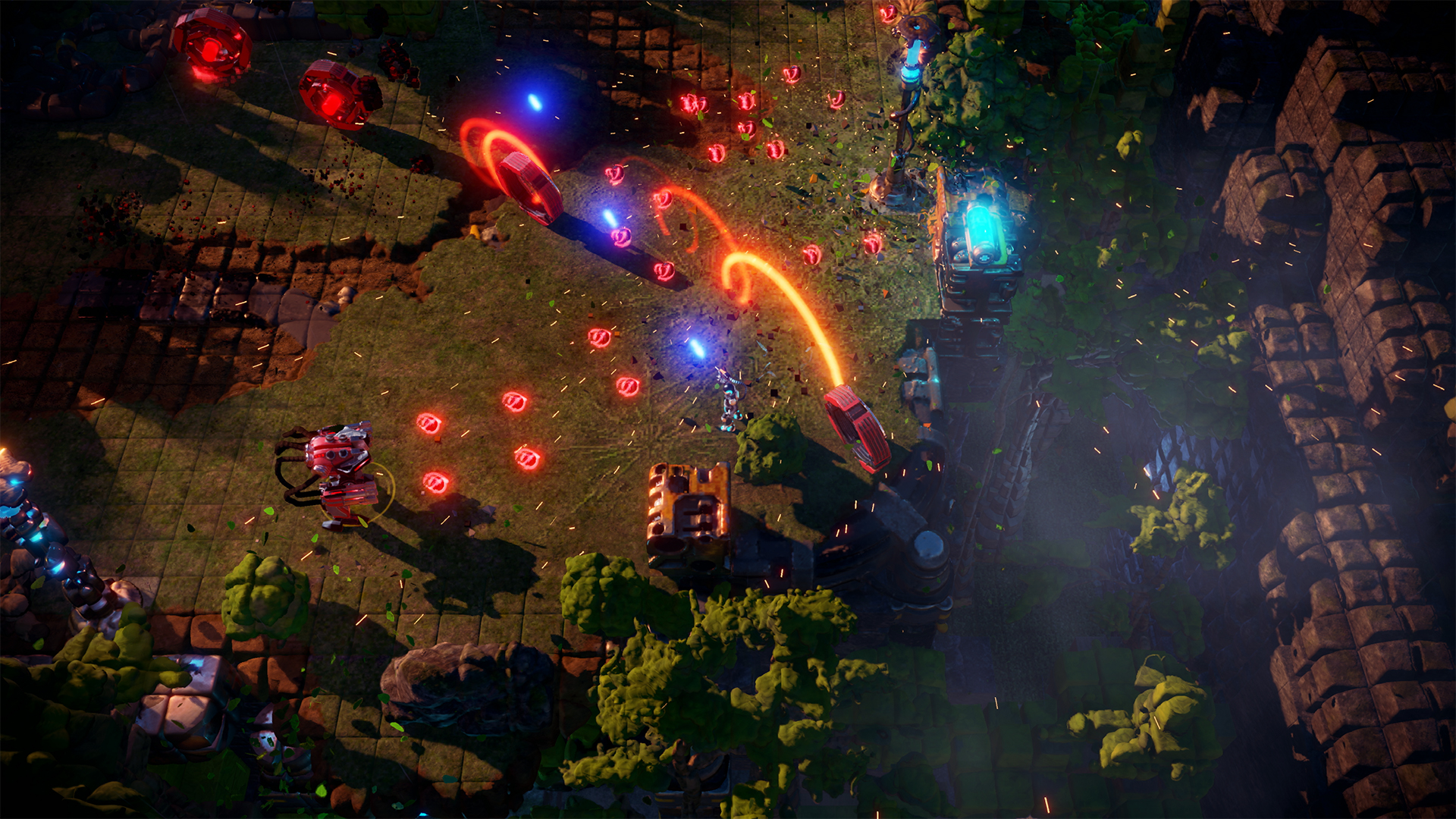

EJ: It does, otherwise you would just quit. It’s like this torture and you have to reward. You can do a cool effect that’s always the same every time, like, ‘Oh that’s so beautiful’, but after you’ve seen it a hundred times it’s not beautiful any more, it’s just the same. Here, every time you shoot something, where you shoot it, what angle you’re coming from, the velocity, even the edge of the cube because there’s four different edges of the cube, the gravity affects the effect, and so everything is different. It’s like throwing rocks at the ocean... It’s this chaotic continuum but there’s some order to the chaos, it’s mesmerising.

HK: But I think ‘satisfaction’ is the keyword. That’s what all this cool new tech allows us to really do, because gameplay-wise, we’re playing with tried-and tested timeless gameplay values. That allows us to focus all of our tech to make that core experience as satisfying and rewarding as possible, and it’s just about improving that second-to-second feedback and experience for the players. When you shoot an enemy it needs to feel good, when you destroy a boss it needs to feel f**king awesome. You need to have a lot of this stuff that feels interactive and dynamic. It’s not just this canned, static cutscene that’s always the same.

EJ: You’re a part of everything, you’re affecting everything. But it’s interesting how we’ve taken the confinement by using the laser beams. It’s a dynamic confinement, rather than just a standard confinement.

OPM: When we were playing, it was about priority – if we took time to shoot the turrets producing the lasers, we had less of a problem with enemies. Was this planned?

EJ: The long-range, short-term thinking. It’s like, ‘I’m dying right now, but if I somehow kill this then I don’t have a problem.’ ‘My life will be erased here forever but somehow I’m going to have to really do something crazy to do that and put myself in great danger – but my future is safer.’ All these decisions... there’s strategy and tactics as well as just pure twitch, so it makes for a really rich experience.

HK: Yeah, because I think the best gameplay isn’t what you see on screen, it’s what’s happening inside your head. It’s all about micro-goals and micro-decisions that the game presents but you also make for yourself. It’s like, ‘Yeah I started this level, I need to save the humans, destroy this turret – but if I spend time on this, then I lose something on the other side’, so that creates a sense of urgency. And urgency and frenetic, high-paced action are two things that go hand-in-hand, so combine that with some over-the-top explosions and I think you have a pretty tight arcade experience.

EJ: Another cool thing that the team came up with is the surround dispatch, where you’re running around, you think you have everything under control – and then all of a sudden a complete circle around you beams down 20 enemies. It’s this dynamic confinement, you thought you were free...

HK: You need to keep the player on their toes. You can’t let them get too comfortable because then it gets predictable and boring. But it’s the gratification that creates gameplay. Actually it’s really interesting because there’s even a few secrets in the levels that nobody has found.

OPM: Oh, go on – tell us one secret...

HK: For example, in the level 1-6, in the bottom right corner, there’s these layers of breakable blocks. There’s this extra one at the end that seems to take a lot more damage than the others, but if you insist on it you get this balloon, and you get this cool sound effect that’s like ‘Secret found’, and this extra path with lots of humans. And that’s part of our philosophy as well – that you want to have this depth but without complexity. The levels are pretty aggressive with how they throw enemies at you and the levels automatically end when all the enemies are killed.

EJ: So, you have to milk everything before you kill the last enemy. But that puts you in more danger.

HK: And once again it goes into these multiple goals for the player, because even if you know where the secret is, it’s not like ‘Oh I’m just gonna go there and it’s gonna feel like work’. You still need to be on the edge of your seat to save the humans, open the secret door, kill the enemies, dodge those beams and still come out in one piece in the end.

EJ: There’s also materialising bridges that actually get materialised out of voxels to hidden levels.

OPM: Nex Machina feels really solid. Do arcade shooters need stable framerates?

HK: Of course, when you’re creating this kind of arcade experience then you have to go for an uncompromising 60 frames per second.

EJ: You can’t have it be unfair, or not your fault. Probably the greatest thing working in games is watching someone enjoy your game and to think, ‘Wow I had a part in giving someone that enjoyment’.

HK: Having that kind of stability in the build and having that kind of nice, smooth framerate makes the overall feeling much more satisfying. Sometimes it’s not really something that your eyes pick up or your ears, it’s just this feeling that you have. It’s just that something wasn’t right there, like the game skipped a beat. But when you have everything working consistently, fluidly, reactively, you get into this zone of feedback... It’s like this sensory overload, it’s almost like being hypnotised.

OPM: What’s the ideal outcome for you when Nex Machina launches?

EJ: I did the original Robotron game back in 1982. To me it’s still one of the classic 2D games as far as action and decisions per second, and kills per second, and explosions per second. It’s super-frenetic and totally involving. There’s been a lot of games since, a lot of Robotron sequels. A lot of them haven’t even captured the magic of Robotron, much less moving things forward. My greatest dream would be that we actually make a game that is taking the best of 2D and 3D, dynamic environments too, taking the new technology, making something simple that we actually maybe almost forget about – and this becomes a new standard that people think about now for the next 30 years.

HK: That’s a pretty noble goal.

EJ: That people would just enjoy it so much, you know? It’s just great to watch people enjoy the game. The other objective is we really want to directly challenge and push the player into an uncomfortable zone. That uncomfortable, challenging zone – there has to be a dimension of play within that. It can’t just be, ‘You’re dead’.

HK: Honestly, I think ultimately we’re talking about the same thing. For me, it was almost down to just making the best possible game. I know that sounds a little bit clichéd, but a good game is something that does stand the test of time. It is something that people will not only fondly remember but also want to replay 10 and 20 and 30 years down the line, just like Robotron. Hopefully the same thing will happen with Nex Machina.

In the short term we want to make a game that’s worthy of, of course, Robotron and Eugene’s legacy. We need to make a game that’s worthy of Housemarque’s namesake and a game that’s worthy of all our fans out there that are expecting quality. I’m just hoping we deliver on that. Forget the delays – if you release a s**ty game then you’re kind of stuck. Now you can patch it, but you only get one chance to make a good first impression.

EJ: A good game is forever.

This article originally appeared in Official PlayStation Magazine. For more great PlayStation coverage, you can subscribe here.

Jen Simpkins is the former Editor of Edge magazine, and is a multi-award-winning creative writer. In her most recent industry role, Jen lent her immense talents to Media Molecule, serving as editorial manager and helping to hype up the indie devs using Dreams as a platform to create magical new experiences.