How a parchment of ideas evolved into the RPG work of art that is Pentiment

Holiday Long Read | Edge magazine explores the making of Obsidian's uniquely eye-catching hit

Your first act in Pentiment is a simple one, yet loaded with layers of deeper meaning. The game begins with the camera zooming in on a thick book, propped up against a large wooden board. Suddenly, it flips open to reveal a page of Latin text – at which point a smooth, oval-shaped stone appears, inviting you to press it down against the page to erase the printed words and images.

Even without any additional context, the process feels taboo – effectively charging you with rewriting history. It's tied to the game's title, too: like a palimpsest, it refers to visible traces of a prior work, scraped away or covered up by fresh paint or ink. As game and narrative director Josh Sawyer puts it, "You're creating your own version of the story that is going down. But also, your story is built upon many other stories that have come before you."

In this particular instance, Sawyer acknowledges the debt to Pentiment's primary influence – one that, for most players, is hidden in plain sight. Those fluent in Latin (and also familiar with Biblical verse) may recognise the opening lines 'In principio erat Verbum et Verbum erat apud Deum et Deus erat Verbum' ('In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God, and the Word was God') as from the Gospel According To John. Which is accurate, Sawyer says, but only because Umberto Eco's historical murder mystery The Name Of The Rose also begins with those lines – the rest of the page is actually Eco's work translated into Latin.

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more in-depth interviews, reviews, features, and more delivered to your door or digital device, subscribe to Edge magazine.

"It's me saying, 'I, Josh, am writing this story on top of The Name Of The Rose – it's inspired by it and builds upon it, and you are telling your own story within this framework as well.' So it was to convey all of these things at once." Having studied the Holy Roman Empire for his history degree, Sawyer decided to move his murder mystery saga forward in time, shifting the location from Eco's Italy to the Bavarian Alps.

"I find the early modern period particularly fascinating – that transition point between the Middle Ages and the modern period – and I'm also more familiar with Germany broadly," he says. Further research into the period threw up a problem, but one that ended up informing Pentiment's story – and, indeed, the developer's approach to historical accuracy in general. "At this point in time, there really weren't very many, if any, monastic scriptoria in existence," he says. "So the idea of the scriptorium of Kiersau Abbey holding onto the past became more of a focus; this place is unable to move forward in time."

Empire state of mind

That theme crops up throughout Pentiment, which spans 25 years in and around the village of Tassing – fittingly, about the same amount of time since Sawyer first mooted the idea of a historical RPG to Obsidian CEO Feargus Urquhart, when the two were co-workers at Black Isle Studios. As art director Hannah Kennedy recalls, it was at GDC in 2019 when the opportunity "to work on something smaller, something more experimental" arose. She had been working on The Outer Worlds as a concept artist, while Sawyer was close to wrapping up work on the console versions of Pillars Of Eternity II: Deadfire. "I had heard whispers of this idea that Josh had for quite a while," Kennedy says. Her own background in printmaking – "I studied it in college, and still do it for fun" – along with the studio's backing meant the stars were finally beginning to align for this long-gestating concept.

By then, Sawyer had found his secondary source of inspiration – one that helped determine the type of game Pentiment would turn out to be, in both creative and practical ways. "I had seen Night In The Woods shortly before it came out, played it shortly after, and I was really impressed by it," he says of Infinite Fall's award-winning narrative adventure. As a player, he was captivated by "a very interesting story from a perspective I had not seen before". As a developer, he was inspired and motivated, partly by the fact that it had been put together by a core team of just three people. "It made it approachable in my mind as something a smaller team could do – that you could tell a moving and very gripping story with a relatively simple gameplay formula."

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Kennedy elaborates: "The structure of that game didn't end up getting in the way of any of what they were trying to do with the story and the experience. It was just enough. But you're really just walking and talking to people, and then you have these little interactive minigames within it to break that up – which we just one-for-one stole from them," she laughs. Though Pentiment was always going to have a larger cast and greater scope than Night In The Woods (with changing seasons, time passing, and a longer, three-act story), Kennedy says the team hoped to capture a similar sense of a world that feels larger than it actually is in terms of real estate, and one that captures a tangible feeling of a community. And, more importantly, that the place itself should feel alive – "not like the whole thing revolves around you".

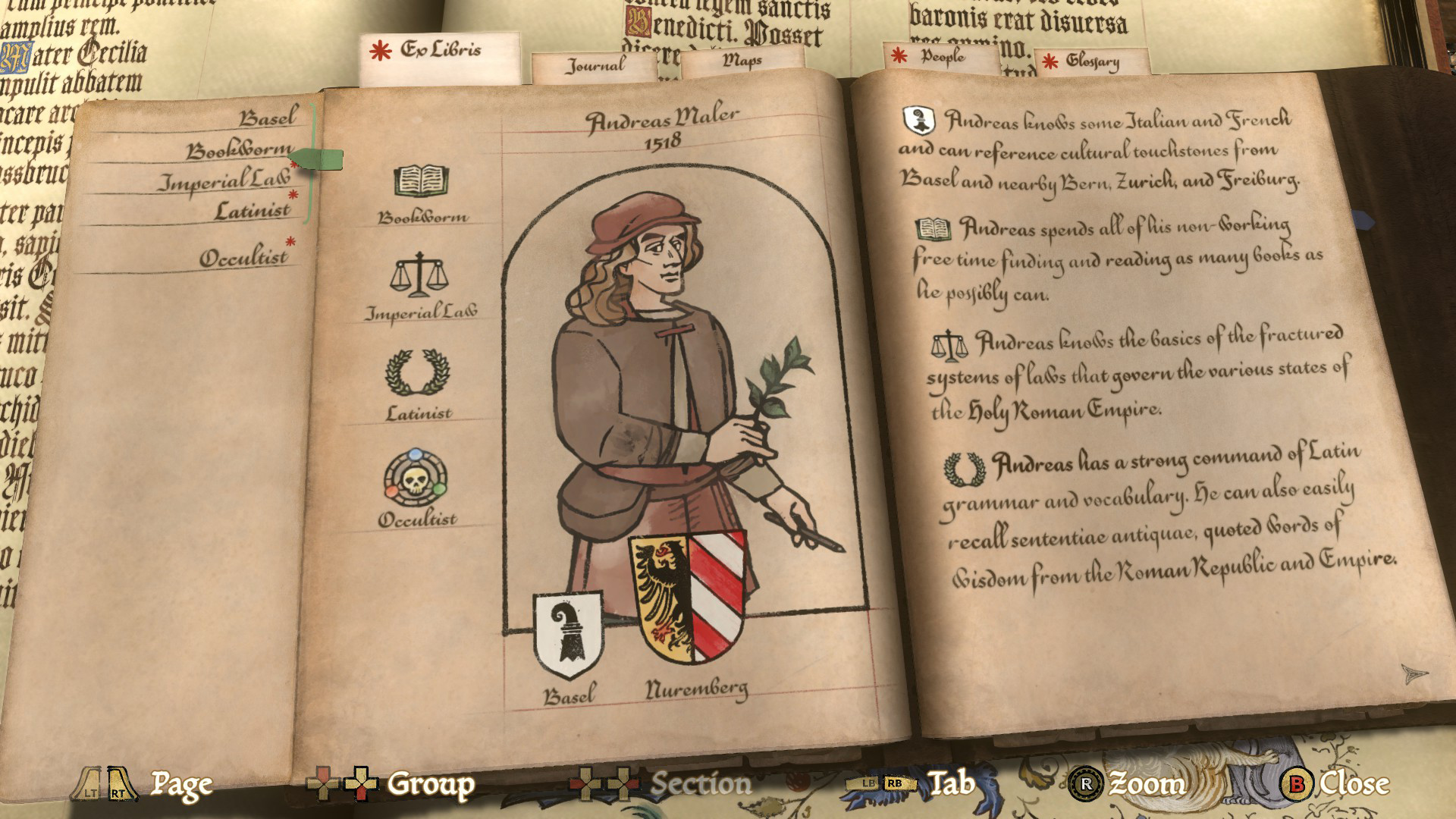

The 'you' in this case is apprentice illuminator Andreas Maler, tasked first with finishing a manuscript originally commissioned to his elderly mentor Piero, then leading a murder investigation when the latter is accused of killing a visiting baron. Though you get to determine his background and areas of expertise, he's no blank slate: an avatar, but one with a context of his own. Maler was based on German painter Albrecht Dürer, Kennedy explains, partly "because there were a lot of parallels to the themes we were trying to [explore]". Dürer, she says, was chosen specifically as "one of the first recorded artists in western Europe that was marketing himself more as a craftsperson and towards individual patrons in the more secular community," at a time when art was almost exclusively formally commissioned by institutions such as the Church. "He even designed his own kind of logo, with two letters nested in each other," she says.

You can see that reflected in the personality of Maler, who can easily come across as a pompous blowhard – particularly in dialogue choices that see him lean on his education for extra insight, an approach that doesn't always find favour among Tassing's working classes. All the same, he also possesses a certain everyman quality – crucial for a man who has to move between the secular and ecclesiastical communities, capable of hobnobbing with the nobility while boarding with the peasantry. "There's always a risk, I think, [with a] fantasy or historical [setting], to make things feel overly formal and stuffy," Sawyer says, citing Derek Jacobi's Cadfael series as a key touchstone for the game's language and tone.

"[Maler] just needed to feel approachable. He needed to feel like a real person. Like you said, he can be a blowhard, or a lusty guy, or he can jump into fistfights if you want him to. Though, of course, you don't have to engage with all that." The key, ultimately, was to make sure that the time period would be no barrier to making its characters relatable. People in the 16th century might have had different problems to our own, Sawyer adds, but "they're not that alien, really".

The olde ones are the best

One of Kennedy's tasks, meanwhile, was making its cast immediately identifiable in a different sense. In defining Pentiment's look, she naturally researched historical printmaking, specifically from western Europe and Bavaria itself. But in capturing Tassing's inhabitants – no small feat, given there are 75 different characters in the game's first act alone – she and her team also studied modern media inspired by those pieces, looking once more for traces of the past. "The Cartoon Saloon animated features were a big one," she says, referring to the five-time Oscar-nominated Irish studio. "We didn't want to copy their style, but we wanted to see what they kept and what they extrapolated upon." Kennedy and her fellow artists watched the likes of Wolfwalkers and The Secret Of Kells, picking up tips from their flattening of space and dramatic stylisation of characters.

One of the biggest takeaways, she continues, was how those films differentiated character silhouettes among a large cast. Given players were going to be spending a large portion of their time in either the abbey or monastery, they'd encounter several characters dressed in habits or robes. "Also, they're going to be really small, and they're going to be stylised," she smiles. "We needed to figure out ways that we could make them easily recognisable to players having only been exposed to them for a little time." The answer was to cheat a little, not necessarily being truly authentic to how these characters would have looked or dressed at the time: "If all these nuns were in the same order they would all have the same habit on." In some cases, it was about adjusting head pieces, with almost geometric shapes to distinguish individuals; in others, it was about body shape and height. "Sister Illuminata kind of looks like a bowling pin," Kennedy laughs.

Deciding when to play fast and loose with historical accuracy and when to lean into it proved challenging at times. Which approach to take was generally determined by the ideas and themes they wanted to communicate, Kennedy says, such as having an abbey and a monastery in such close proximity: not entirely unheard of, but very much "a fringe case". Maler's walk cycle was briefly a cause of consternation, adapted by the animators once research revealed that, at the time, people walked toe-to-heel rather than vice versa. "Shoes weren't fully soled at the time," Kennedy says, "so you wouldn't want to land on the hardest part of your foot first. And the first test of Andreas walking like that looked ridiculous, like he's tippy-toeing around everywhere. And in cases like that, you also have to think about the player experience: we want to be accurate, but we also don't want this to be distracting to a modern audience."

Sawyer, a stickler for authenticity, also caused a few headaches for the art team when he observed that characters shouldn't wear hats inside. "We're like, 'What do you mean?'" Kennedy recalls. "The hats were all attached at this point – they weren't separate pieces." But she knew he was right during the meal scenes in particular, where it felt strange to see everyone gathered around the table with headwear still fixed in place. "It was a big ask," she says, "but it also presented us with the opportunity to do some jump scares with people's 'secret hair'. Like how Peter [Gertner] has a pretty dramatically receding hairline that you never get to see without his hat, because his hair is sticking out of the sides." (As we say, relatable.)

Those scenes of breaking bread with the townsfolk feel particularly significant during Pentiment's first two acts: a way to introduce a sense of routine to Maler's days, but also to establish class distinctions, both in the 1 conversational topics and in the foodstuffs consumed. And, of course, to pick up a few hints at potential motives for the various suspects (some of which are, Sawyer reveals, dependent on the order in which you reach for the various comestibles).

"We knew we were going to have investigation events, but only a limited number of them and only a limited number of suspects. But I didn't want the player to not get exposure to the other people in the town. So the meals are a way to sort of force the player to go and sit down with a bunch of different people in the community." He points to the game's second act, where you have back-to-back meals with the increasingly impoverished Gertners and then the abbot, who complains about funds being tight while still eating like a noble. "You end the meal with half the food still on the table and you're like, 'What the hell?'" There was a temptation among the team to call more attention to this, but Sawyer said no. "Players will notice it. We don't need to actually call it out explicitly because it's right there in front of you. And thankfully, a lot of players have [commented on] the stark difference in social status and wealth."

Even so, Sawyer recognises that it's important to spell some things out – namely, when your dialogue choices and actions have had some kind of effect. Though even here there's a degree of ambiguity in the phrasing. 'This will be remembered', you're told, which not only sounds more ominous than the Telltale alternative, but doesn't let you know who is going to remember it – or, just as crucially, how. You might argue that this should be left unsaid, but Sawyer says he never considered that option. "Making RPGs for long enough has settled that debate in my head," he says. "Tell the player what's going on. Sure, some people will say, 'Oh, I don't want to know that,' but almost always it's a negative reaction [if you don't]." Besides, he says, the story is structured so that the payoff to a particular setup could still be hours away.

"Not all of them are super important," he says, "though they might be, and there are landmines buried here, so you should think a little more carefully about the choices you make. But I like 'This will be remembered' because it's not even necessarily that it will be remembered by the person you're talking to. In some cases, it's another person who's nearby or someone who hears about it." In a compact community such as Tassing's, you can be assured that somebody is going to remember what you said or did.

Or, for that matter, what you didn't. With time against you, your investigation of the baron's murder will see you discover evidence that is, at best, circumstantial. Indeed, you will often discover possible motives for other suspects after the fact. In keeping with the themes of The Name Of The Rose, Pentiment is a game in which you interpret meaning from what you are able to uncover, but since that's subjective, you may never have a complete picture of how events really played out. In the background you might even detect faint traces of an untold story – or, in the case of one character, a deliberately withheld one, should you choose to take pity on one suspect with a clear and obvious rationale for murder.

This was always part of the plan for Pentiment, Sawyer says, spurred by hearing another developer ("I won't name names") outline their pitch for a murder-mystery game where there was always a single, conclusive answer. "It made me think: how would I approach that? How would I approach a murder mystery in a roleplaying game? To make your choices feel important and meaningful, without later invalidating them by telling you that actually you were wrong, or the inverse, saying no matter what you picked, it was actually right." The 16th-century setting was a boon in this regard, given the lack of forensic evidence or investigating officers. "We specifically removed things like alibi, because all that does is exclude people. It really comes down to motive and plausibility and how much you think," Sawyer says. Or it might simply come down to how much you like or dislike the characters in question: the monastery's antagonistic and high-strung prior Ferenc is overwhelmingly the most popular choice for the chop, he adds, with two-faced scribe Guy firmly in second place. "He's a huge jerk," Sawyer laughs. "There are extenuating circumstances but most players don't find out about those. [When they do], in some cases, they'll pull a 180."

A friend in needles

As the game celebrates its first anniversary, we concede to Sawyer that we haven't replayed it since; he responds by saying he knows plenty of others have felt similarly disinclined to go back. "I think there's less of a desire to immediately replay than you might find in a 1 Just a small selection of the strange and sometimes amusing marginalia awaiting discovery in Pentiment's illustrated manuscripts. 2 Ferenc's book, which Maler sees the prior scribbling inside in the scriptorium, is very much an object of interest during his investigations. 3 These images represent the first pass of the protagonist's design, ahead of any colour considerations. "I started trying to design Andreas initially based [on] Josh's context of who he thought he was going to be," Kennedy says. "He had the character profile [in place], but we knew players would get to choose their own version of him" traditional roleplaying game where there's so many aesthetic options and class options and build options," he says. "Though some people have said they've done like five playthroughs in rapid succession, which seems crazy to me. My thinking on it was much like Night In The Woods, which is a game I come back to, like, once every year or year and a half."

He acknowledges that he finds it "emotionally difficult" watching other players, but then this is a game that refuses to shy away from the brutal realities of the time: plenty of characters you meet in the first act are no longer around by the third. "It's a weird analogy, but I watched Dancer In The Dark, the Lars von Trier movie with Björk. And it's gutting. It's devastating. What an incredible movie. And I got it on DVD and started watching it again, and getting upset. I was like, 'What am I doing?'"

Pentiment, however, isn't nearly as unremittingly bleak; we return to the Cadfael comparison when discussing the game's final act (which, even now, we're keen not to spoil) and a newfound character trait that allows you to deploy a range of withering put downs. That levity, Sawyer says, is important – and historically accurate, too. "It's easy to look at the past and say, 'Oh, what a dark time. What an awful world. There was no pleasure at all'. But that's not true. We know that people did have joy in their life. And the most popular books in this time period were scatological stories. They're extremely sexual, extremely crude – there are all sorts of jokes about crap and piss. And people thought they were hilarious. And so having characters have a sense of humour and ribbing each other and insulting each other and things like that – you need a little of that or else it's just it's too much to take."

Not long over a year on, perhaps now is the perfect time to revisit Pentiment, but as we reach the title screen again, we find ourselves hesitating to reach for that metaphorical stone. It's not that we're unprepared for its darker moments. Rather, having seen the masterpiece that Maler began in act one finally receive its finishing touches, it's a powerful sense of having illuminated our own version of history – one we're reluctant to paint over. That in itself is testament to the emotional impact of Obsidian's adventure, and to the way it is so much more than the sum of its own pentimenti – even as the traces of its biggest influences can still be detected in the cracks.

This feature first appeared in Edge Magazine issue 392, which you can pick up right now here.

Chris is Edge's former deputy editor, having previously spent a decade as a freelance critic. With more than 15 years' experience in print and online journalism, he has contributed features, interviews, reviews and more to the likes of PC Gamer, GamesRadar and The Guardian. He is Total Film’s resident game critic, and has a keen interest in cinema. Three (relatively) recent favourites: Hyper Light Drifter, Tetris Effect, Return Of The Obra Dinn.