How Disco Elysium captures our current political moment

Disco Elysium's left-leaning messaging is clear, but the questions posed by its central story leave no easy answers

The city of Revachol is the site of a murder. We begin navigating it with questions about who did it and why. The city returns answers not only to those questions, but to bigger, broader ones too. Questions that would usually be beyond the purview of a detective on a homicide case.

What events and forces shaped this place into the one it is today? Why has the district of Martinaise and its people seemingly been abandoned to poverty and semi-lawlessness by the authorities? Whose interests are being served by your investigation in Disco Elysium and what political factions do they represent? The context that this rich political, social and economic history provides is designed to do more than make Revachol into a believable place. It is a diagnosis of our current political moment, a critique that we can use to help orient ourselves and, perhaps, even start searching for a way out.

Disco Elysium's setting was formerly the site of a communist revolution that established the Commune of Revachol. It didn't last long. The Coalition of Nations brutally put the communists down, divided the city among themselves, and enforced a free market capitalist system. The results are depressingly apparent in Revachol's dilapidated district of Martinaise. "The literacy rate is around 45% west of the river," Joyce Messier, a negotiator sent to parley with Martinaise's striking union, tells our protagonist. "Fifty years of occupation have left these people in an *oblivion* of poverty."

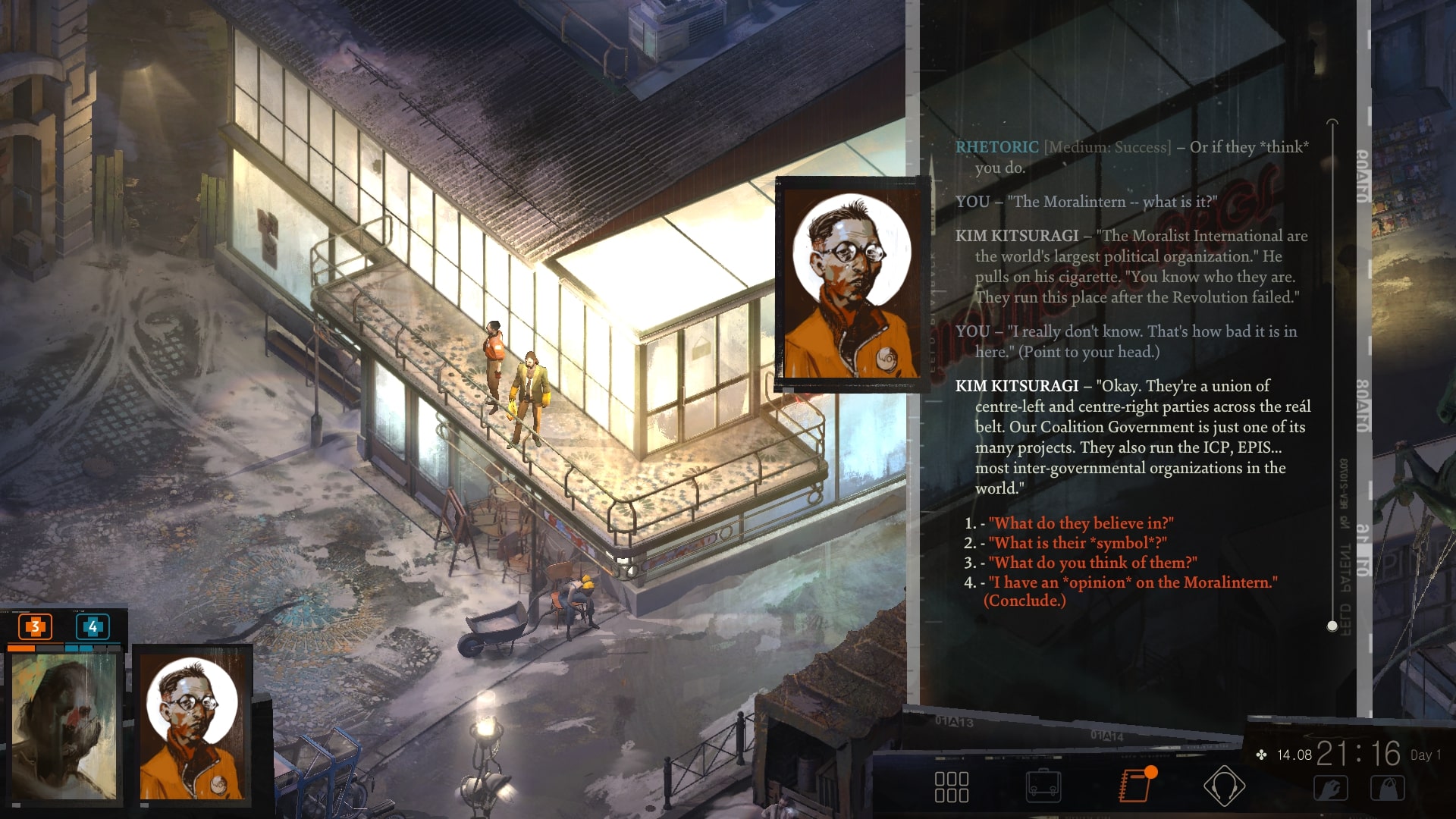

This state of affairs is overseen by the Moralist International, a union of centre-left and centre-right parties that professes to represent the cause of humanism, but whose primary concern is transparently the preservation of capitalist interest – a Coalition official happily tells us that "the Coalition is only looking out for *ze price stabilitié*", arguing that inflation in Revachol must be prevented, comparing it to a heart disease that could block the "normal circulation of the economy". The people of Revachol don't matter. Their suffering and oppression is only significant as a necessary symptom of the system functioning as intended.

A class of its own

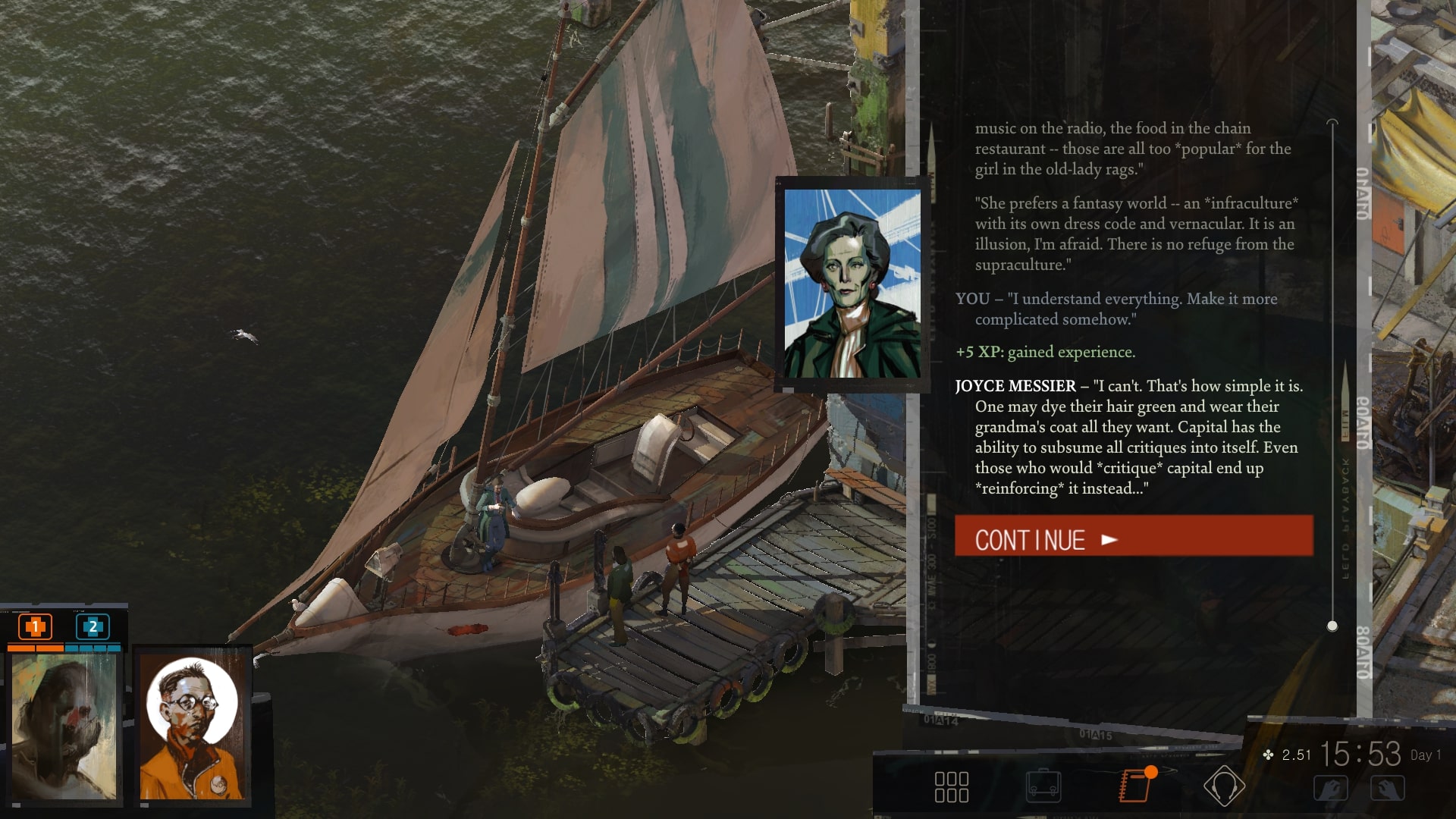

The most biting aspect of this critique of capitalist exploitation can be found in the cynicism of those who represent Moralism, or at least, its interests. The aforementioned Joyce Messier is its perfect embodiment. She does not believe in the facade of humanity Moralism presents to the world, and is under no illusions about what it has done to the people of Martinaise. She tells you how bad things are, freely admitting that the pieces of legislation put in place by the Moralist Coalition to govern Revachol are there to keep "the city in a [...] laissez-faire stasis to the benefit of foreign capital". This corrosion of belief via cynicism, this depiction of a system that continues to operate unimpeded despite few believing in it, feels all too familiar.

This critique of liberal capitalism's hypocrisy, cynicism, exploitation and deep-rooted connections to colonialism, is particularly powerful in recognising the precarious position it finds itself in. It has reached a stasis that seems, paradoxically, both insurmountable, and on the verge of collapse. Moralism relies on this contradiction. It's unofficial motto, "for a moment, there was hope", underlines the degree to which its dominance depends on the preclusion of the idea that a better world is possible, that there is no alternative, echoing the End of History sentiment that created the (rapidly disintegrating) political consensus of our lived reality.

Despite growing dissatisfaction with the status quo in the real world, it has, indeed, proved difficult to imagine an alternative. The oft-repeated phrase attributed to literary critic and political theorist Fredric Jameson, that is is easier to imagine the end of the world than it is the end of capitalism, has almost become a cliché. However, the mistake Joyce makes, and one that we should avoid, is to assume that this means an alternative won't emerge nonetheless.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

In Disco Elysium, the potentials of an alternative readying to emerge bubble under the surface. Moralism's stasis has created a blockage under which pressure is building. Left and right populists are building momentum, represented by striking union members and fascists spouting their vile rhetoric on the streets. In a context in which support for centrist parties has collapsed across Europe against a backdrop of reinvigorated extremism, it is not hard to recognise the parallels. Neoliberal capitalism, centrism, Moralism, or whatever else you want to call this zombie ideology, has no adequate response in the fiction of Disco Elysium, or in the real world. As a result, people are looking elsewhere.

And where does Disco Elysium suggest we should look? Not, of course to fascism, but neither is the game's communist faction presented as being an entirely unproblematic solution. Evrart Claire, the union representative, is an emblem of the corruption and cronyism associated with the old mode of soviet state communism. Given that Disco Elysium is developed by a studio from Estonia, a country that had to endure the oppression of soviet occupation, it should be no surprise that they refuse to romanticise this brand of communism, despite expressing a profound disappointment with what came after.

Disco Elysium is my game of the year because it made me care about a lost shoe

In the figure of The Deserter it seems to suggest that this communism is at a dead end. His diagnoses of the ills of capital chimes strongly with the critique that the game offers: "The combined might of international capital, all at once – all the greed and terror in the world – tore into Revachol," he says, remembering the bloody destruction of the revolutionaries; "The mask of humanity fell from capital. It has to take it off, just for one second. To do the deed."

But he does not represent an adequate response to this injustice. He is a zombie going through the motions who himself believes that the movement he represents is dead. If you tell him that nothing in history is guaranteed, that revolution is still a possibility, he will reply, "no. The material based for an uprising has eroded, the working class has betrayed mankind and themselves". Like the moralists and the capitalists, like Joyce Messier, he has ceased to believed in History. He has consigned himself, and hope, to the past.

Important to the way Disco Elysium paints a picture of its political factions is that it avoids the trap so many video games fall into when trying to approach politics with nuance. This is, to take a 'both-sides' approach that, in attempting to acknowledge potential failings, ends up representing all political factions as equivalent: inherently evil, hypocritical and corrupt. This produces a nihilism that leaves us with the stasis of the Moralists. If everyone's the same, why bother?

Disco Elysium finds another way. Even distorted by the oversight of Claire, the game suggests that there is something of value in the ideals and principles that underpin its leftist factions. The Hardie Boys, for example, might initially appear to be little more that corrupt thugs enforcing Claire's agenda, but this is complicated when we learn about how Martinaise was effectively abandoned to lawlessness by the RCM – the de facto police force that you work for.

When Hardie Boy member Eugene protests that you had no idea what it was like before they became a pseudo-vigilante group, exclaiming "we had three shootings a week, kids dead – you cops haven't shown up since the thirties," he appears to express genuine care for his community. There is undeniably something to admire in their solidarity, too. In the course of our investigation, we learn that the Hardie Boys have confessed to a murder they didn't commit to protect someone else. Not only that, they insist on going down as a group. They look out for their community and they look out for each other.

Dance dance revolution

In a world where everyone is encouraged to look out for themselves, Disco Elysium suggests we should remember the value of collectivity, camaraderie and community. The Deserter has forgotten that though the communism he identified with is dead, the values that brought people to its cause in search of a better world remain as valid as ever. Bleak as it is, those values exist in Martinaise. They exist in us. Their latent power has the potential to lead us towards better horizons.

"Disco Elysium suggests we should remember the value of collectivity, camaraderie and community."

Coupled with these principles, Disco Elysium reminds us of what necessarily fuels them. Though it is a game willing to bend to the players' will, it is, I think, near impossible to reject its offer of sharing in the empathy it has with its characters. Poverty; loneliness; abandoned and beaten children; alcoholism; despair: these are the products of the violent events of the past that shaped Revachol and the uncaring brutality of the present in which its people must live. Where that has created an ugliness in its characters, Disco Elysium does not always ask us to forgive them, or suggest they shouldn't be judged. It does, however, remind us that we are all shaped by the world we have to live in. It's people deserve better. We deserve better.

When we first arrive in Revachol, it feels like a city crumbling at the edge of time, history a backstory that's reached its conclusion. By the end, it is clear that History is primed to erupt once again. Will it lurch further towards darkness and embrace the horrors of fascism? Or will it embrace empathy, solidarity and collectivity on the path to a better world. This is Disco Elysium's political moment, and it is ours too.

For more, check out the biggest new games of 2019 on the way, or watch the video below for a guide to the year ahead.

Paul Walker-Emig was once a video games journalist, before he moved into PR. During his freelance career, Paul wrote for GamesRadar, The Guardian, Retro Gamer, Wireframe, Kotaku, VICE, VG247, OXM, and more. He runs the Utopian Horizons podcast, which covers a different utopia, dystopia, utopian thinker, or movement each episode. He also runs the podcast getObject, which is a video game website and podcast based around collectible items.