How Ensemble's final game went from skunkworks experiment to part of Microsoft's biggest series

Interview | Exploring the making of Halo Wars with the people who brought it to life

Given the opportunity to do anything, what would you choose? When Ensemble Studios' management team asked itself this question, in late 2004, there was a consensus: not this. The studio had spent the better part of a decade iterating its brand of real-time strategy, following its 1997 debut Age Of Empires with two direct sequels, a number of expansions, and a spinoff in Age Of Mythology that not only pivoted this winning formula into fantasy but also its first fully 3D engine. Since Ensemble's acquisition in 2001, this path had been followed under the firm encouragement of Microsoft. Now, as the team began to look beyond Age Of Empires 3, it was growing restless. The RTS had been all Ensemble had ever known, and it wanted to spread its wings.

Some in the studio's leadership were keen to try their hand at an MMORPG, spurred by the wildly popular beta of World Of Warcraft; others suggested an action RPG in the vein of Diablo. Both were backed enthusiastically, but lead programmer Angelo Laudon floated a more conservative option, one that would help keep the suits upstairs happy: stick to the RTS format on which the studio had built its name, while expanding beyond the PC audience.

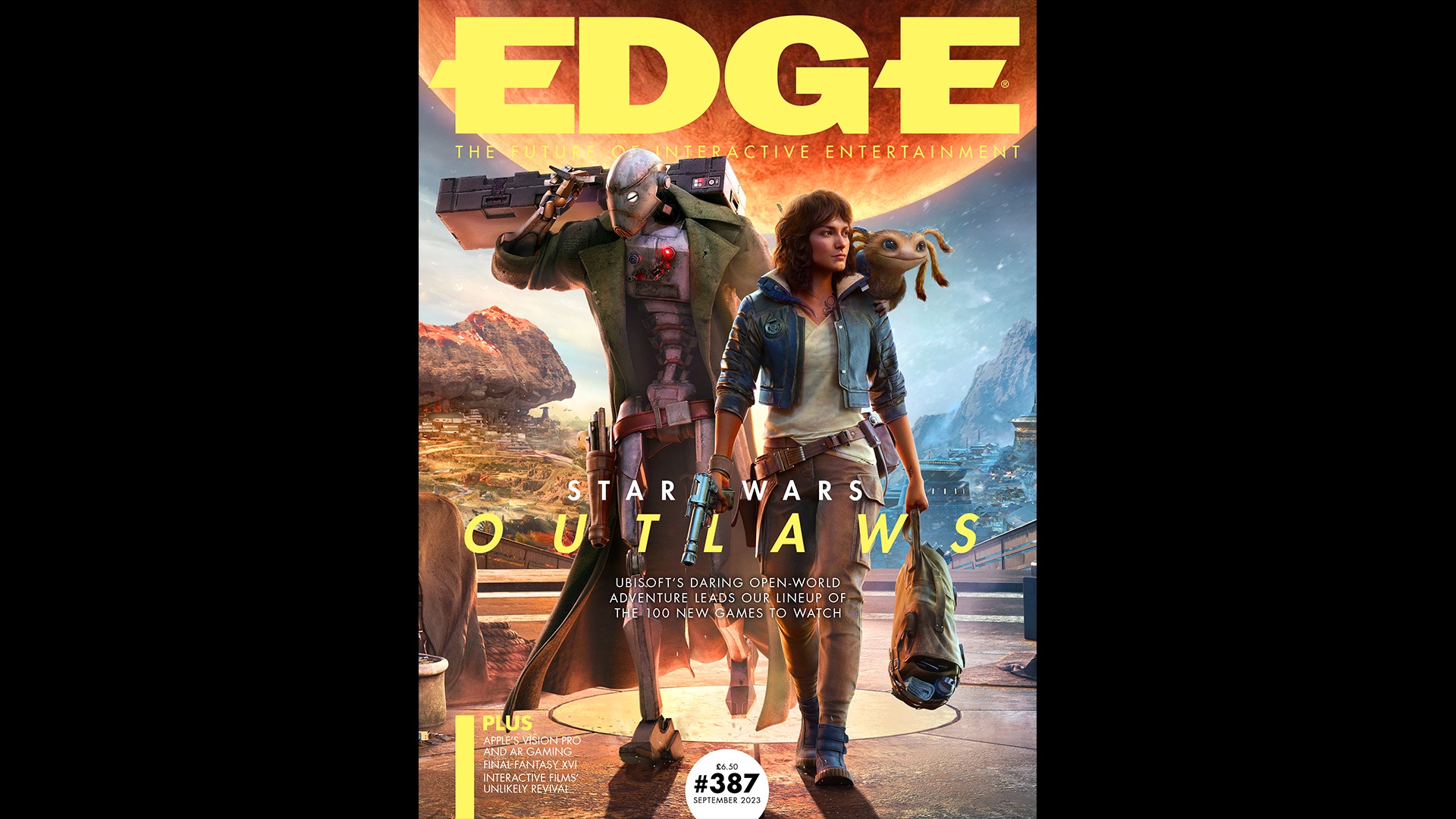

This feature originally appeared in Edge Magazine. For more fantastic in-depth interviews, features, reviews, and more delivered straight to your door or device, subscribe to Edge.

At the time, the most high-profile example of a console RTS was StarCraft 64, a clumsy port of Blizzard's PC classic that ran poorly and lacked essential features. When Ensemble's own Age Of Empires 2 had been brought to PlayStation 2 a few years before, the port did little more than tie cursor movement to the left analogue stick and the Select button to X. "Angelo and I always felt like there were ways to pull it off that nobody was doing," Halo Wars producer Chris Rippy says. The plan, then, was to build a truly console-first RTS from the ground up, something that could live comfortably on the soon-to-launch Xbox 360.

The bulk of the studio was tasked with finishing Age Of Empires 3 before moving on to the Diablo concept, another team was put onto the MMO project, and a final group – composed only of Laudon, Rippy and four others – got to work prototyping a console RTS codenamed 'Phoenix'. One of those four was Graeme Devine, a well-travelled designer and programmer whose credits spanned Doom 3 and cult puzzler The 7th Guest. Studio leadership reckoned his talents were being wasted coding Age Of Empires 3, and suggested he take the reins of Phoenix's design. Relatively new to the studio, he hadn't yet burned out on the genre – and previous experience had taught him not to write off experimental console ideas. "I thought back to my time at Id, when we were just beginning Doom 3, and Halo came out for the first Xbox," he recalls. He and his colleagues dismissed the idea of a console FPS outright. "And then we played Halo and were like, 'Oh. Look at that. That's pretty darn playable'."

I can see your Halo

"The complexity of the game was difficult for console players... we were sending builds out and people were playing them and they weren't having fun, because it was just too hard"

Achieving something similar with Phoenix wouldn't be easy. The RTS was perhaps even more bound to PC and mouse-and-keyboard controls than the FPS before it. Rippy lists some of the questions that faced the team: "What was it like to select units? What was it like to move units? What was it like to gather resources? It was really just the most basic things." In search of answers, the team dedicated the first year of development to making a fully functional console port of Age Of Mythology to demonstrate that intuitive console controller support was even possible. "We always felt, at least at the beginning, that we were a skunkworks team off to the side," Rippy says. "We needed to prove ourselves." Tinkering with narrative, meanwhile, Devine decided that the game would step away from the historical settings – fantastical or otherwise – to which the studio had previously been tied. Phoenix would instead be a sci-fi epic that drew on War Of The Worlds and 2001: A Space Odyssey. "Humans go to the Moon, we find structures on the Moon, and we set off a cosmic car alarm," Devine says. An alien race called the Sway would follow the noise, triggering an invasion of Earth.

Asymmetry was key. As in StarCraft, the human and alien factions would sport distinct unit types, abilities, upgrade paths and playstyles. The Sway would be able to blanket sections of the map in a fog of war, while the humans relied on stealth tactics. Both would advance through technological stages – much like the eras in Age Of Empires – but the Sway would do so by sacrificing their own units, adding a new dimension to skirmishes. Designs changed often, and the team's small size meant it could nimbly prototype and implement new ideas. "One of Ensemble's strengths was to playtest every day," Devine says, with the rest of the studio often joining in to give pointers. Eventually, they honed Phoenix to a state where they felt it was fun to play. "That was the point where we went to Microsoft."

The publisher hadn't greenlit any of Ensemble's smaller prototypes in the past, but it liked Phoenix. Microsoft was keen to have one of its most lauded studios produce something for its new platform, and seemed impressed by what the team had produced. There was just one snag. RTS had no proven console audience, and executives worried that Phoenix would struggle to sell without attachment to a bigger brand. Ensemble could develop the prototype into a full game, Microsoft said, on the condition that it became a Halo spinoff.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Devine took this hard. He had spent a year building out a world of alien races, languages and future history. Now, he was being told to chuck it away for a series about which he knew little. "I baulked," he says. "I baulked badly. I did not like the idea." He was given the weekend to think about it. Then the arrangement was placed in stronger terms: if the team didn't get on board with the Halo pivot, there would be layoffs. "Well, OK, then," Devine reasoned at the time. "I guess I like Halo."

Bar the control system, which the team felt they'd just about cracked, most of the existing design work couldn't neatly map onto the Halo universe, making it redundant. And while Devine found a richer world in Halo than expected, the transition was made more complicated by the fact Ensemble was now working with another studio's IP. To start their relationship on the right foot, Devine and Rippy visited Bungie's headquarters in Seattle to demo an early build. The atmosphere was tense. Many Bungie staff seemed confused. After hesitations, Ensemble was given permission to add to the Halo canon – ideally in a far-off corner of the universe.

Devine remembers Bungie's pitch: "Why don't you set this 100,000 years before the events of Halo, in the time of the Forerunners?" Ensemble was on board, but not Microsoft: "'No, we want Spartans'." Except Ensemble couldn't use the one Spartan everyone knew. Master Chief – and indeed all of Halo's other central characters – were off limits, as the team skirted carefully around the in-development Halo 3 and the (ill-fated) Halo film. With Bungie's assistance, Devine created a new crew of UNSC soldiers that Ensemble could play with, avoiding the risk of stepping on any toes.

Give us space

While Halo Wars was progressing, Ensemble's other projects were struggling. The MMO team had pivoted that game into another Halo-themed spinoff without Microsoft's request or approval. The Diablo-style ARPG project was cancelled when Microsoft refused to greenlight it, and the prototype that replaced it – a Zeldainspired spy game called Agent – fared no better. The team was split up, and its staff distributed among the MMO and Halo Wars. The extra hands were sorely needed. Despite being the only active project at Ensemble that had received Microsoft's approval, Halo Wars had the smallest team. But, as senior staff rolled off other projects, the balance of what was once a lean, nimble unit shifted. Devine was left to focus on the narrative, while lead design duties were handed over to Dave Pottinger.

A veteran of Ensemble who'd worked across all of the studio's releases, Pottinger immediately spotted problems: "The simulation was floundering, the pathfinding was pretty awful, and the computer-player AI was nonexistent." Many of the system improvements the studio had developed for Age Of Empires 3 hadn't been brought over to Halo Wars, while many of the design ideas borrowed from that series proved unworkable on console. "The complexity of the game was difficult for console players," Pottinger says. "When I took over as lead designer, we were sending builds out and people were playing them and they weren't having fun, because it was just too hard." Soldiers differentiated only by their weapons might work in a medieval setting but they looked confusingly similar in the world of Halo; selecting individual units from the hundreds on screen was a pain using analogue sticks; and managing an economy and building a base bogged down the momentum of skirmishes.

Under Pottinger, the game was streamlined. The economy was changed to a two-resource system that didn't involve individual gatherer units; freestyle base-building was pared down to a preset building system; and a Select All option was added so that players could instantly control their entire force. Difficulties remained, though. Halo Wars was now a console game, an RTS and the next entry in Microsoft's biggest game series. But which was it first? "We had a lot of internal debate, really right up until the end, about the priority of those things," Pottinger remembers. "In my view, it was: Halo, console, RTS. Once you decide to make a Halo game, you have to deliver a Halo game."

No wonder, then, that the Spartans were put front and centre, given the ability to hijack Covenant vehicles, and made an essential part of the UNSC roster. In some ways, though, this was anathema to Ensemble's RTS principles, limiting players' strategic options by encouraging them to rely on a specific unit. But finding a balance between compelling and console-friendly design was always the challenge. "We had to pull back on some depth, and, honestly, we pulled back too much," Pottinger says. "Then we ran out of time to put the right amount of depth in. I think about Halo Wars as a lot of missed opportunities."

Yet when the game finally launched, those missed opportunities weren't as clear to players as its makers. Halo Wars was popular enough to get a sequel – albeit not within the same studio. With the MMO project cancelled several months earlier, Microsoft announced ahead of Halo Wars' release that this would be the studio's final game. Ensemble, then, spent its last days working in the very genre its leadership had once been desperate to escape. It made sure, at least, to go out with a bang. "A lot of people thought about Halo Wars not necessarily just as a footnote to Microsoft," Devine says, "but as what Ensemble can do when we're at our best. And it was Ensemble at its best."

This feature originally appeared in Edge magazine. For more fantastic features, you can subscribe to Edge right here or pick up a single issue today.

Callum Bains is a freelance journalist with words in PC Gamer, Edge, VG247, and a whole bunch of other places. He worked as a news writer at TechRadar for a while, covering all the latest happenings in the wide world of video games. He likes writing snappy features, forcing in tenuous metaphors, and the thrill of buying cheap second-hand tech that may or may not actually work. Callum can often be found replaying RPGs to explore their every narrative choice, or evangelising about the excellence of Company of Heroes 2.