How The Last of Us finally fixed the longstanding problems of Uncharted

You wouldn’t normally praise a remastered set like Uncharted: The Nathan Drake Collection for what it removes. In the case of Naughty Dog’s eternally imperiled thief, however, the deletion of time - those years between each boisterous game - has created a new kind of narrative. The back-to-back presentation tells a fascinating story on the side, of a studio discovering and mastering its craft right in front of you. Questionable moments that protrude awkwardly in the first game subside in sequels, and problems that took years to solve are crushed in a matter of hours. But, as with any good story, there’s a twist: The end of Uncharted’s longstanding problems doesn’t come in The Nathan Drake Collection. It comes in Naughty Dog’s next game, The Last of Us.

If I had to summarize most of the positive sentiment about The Last of Us, I’d say that it’s predominantly weighed in the direction of Naughty Dog’s storytelling. We remember the texture of its dilapidated world, the impassioned voices bringing Joel and Ellie to life, the growth of their relationship and the bitterness of the story’s outcome. None of that exists in a vacuum, however, and so much of it is expressed in the game’s design as a stripped-down stealth-like, made jagged by brutal melee combat and truly dangerous men and monsters.

For years and for multiple games, Naughty Dog worked to perfect close-up fighting and sneaking, and though I can’t say exactly to what extent the Uncharted and Last of Us teams influenced each other (there was certainly crossover in terms of personnel), the evolution of those systems is at least perceptible from the player’s perspective.

You have to start by acknowledging that hand-to-hand combat is rarely the showcase in a shooter like Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune. It’s more like a rug draped across a rough spot in the floor, that spot being what happens when an enemy is so close it makes aiming too awkward. So, as is a common human tactic, we solve the problem by punching it and kicking it until it falls down. The brawling in Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune is meant to evoke the kind of improvised biff-pow-ing that Indiana Jones might enjoy. It’s flashy and not so violent that you’d wince at the thought of a cracked jawbone.

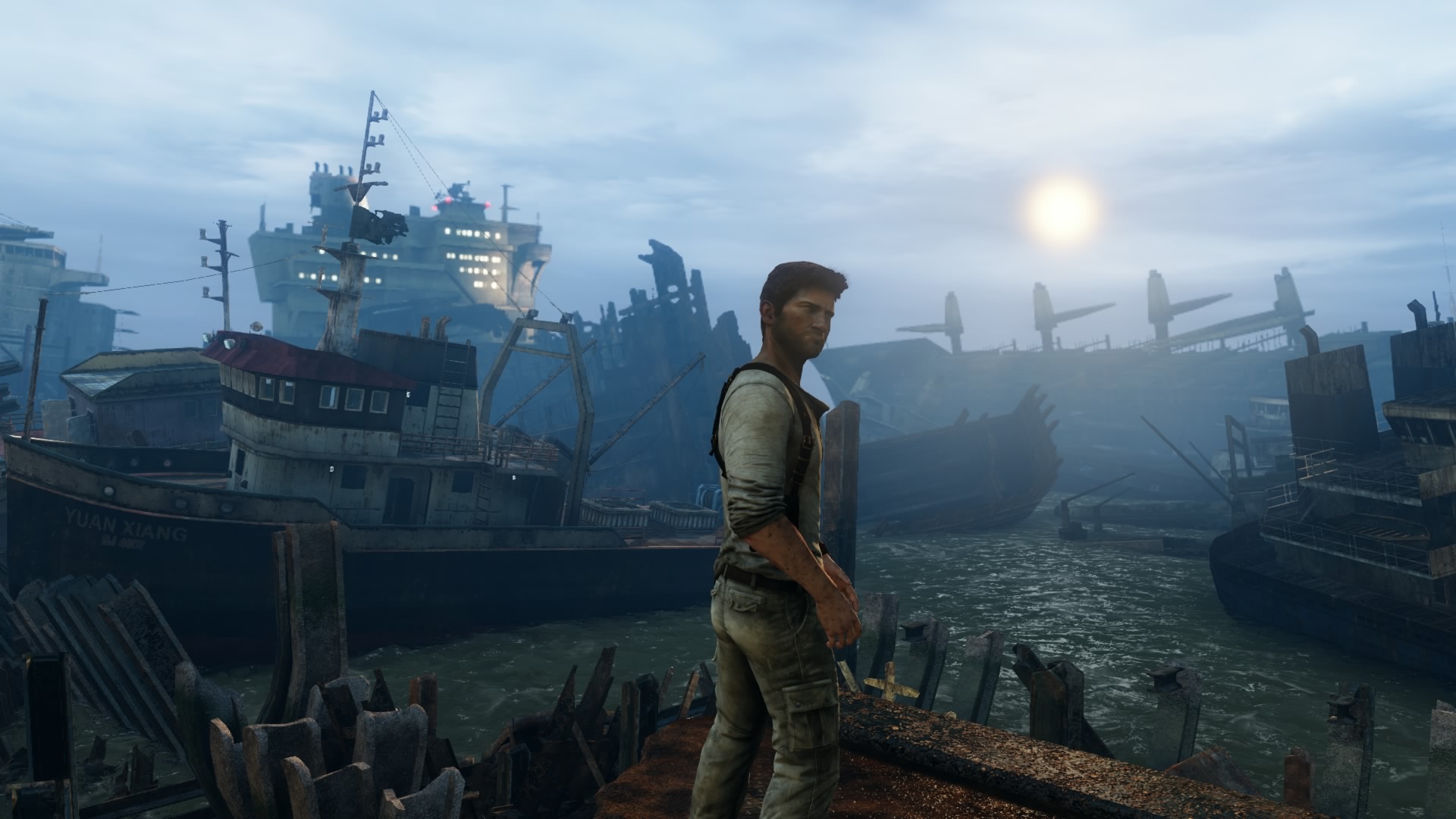

Outside of the slick presentation, though, the punching in Uncharted feels like a carryover from the PlayStation 2 era. What’s meant to be a reactive bit of improvisation on Nathan Drake’s part is a stuttering, combo-driven lull in combat, almost as if his scuffle exists in its own bubble outside of space and time. And why require memorization for certain attacks, spread between two different attack buttons, as if Drake isn’t just the sort to flail his way out of trouble? It didn’t work and Naughty Dog ditched it.

For Uncharted 2: Among Thieves, there’s a purity to all the punching. Nathan will swing wildly if you simply mash the square button, fitting for a man improvising his way out of another misadventure. The only other wrinkle is a counter button, which introduces a sort of pugilistic back-and-forth cadence to the fights and stops them from being entirely one-sided. Mission not quite accomplished, though: Unlike nearly every other facet of Uncharted 2, the fighting still feels like it’s happening on its own little stage, divorced from the rich environments and seeming more than a little … rehearsed.

When we get to Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception, the impromptu boxing ring has expanded, not with bloat but the long-awaited acknowledgement of the world around it. Now, Drake will automatically grab pots, pans and whiskey bottles - anything that can be held and swung into a bad guy’s mug. Drake can push goons onto tables and slam them into walls without interrupting the show. It’s almost there, but in taking one step too far, Naughty Dog adds an extra button-press for grappling and tossing enemies about, something that could have been contextual.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

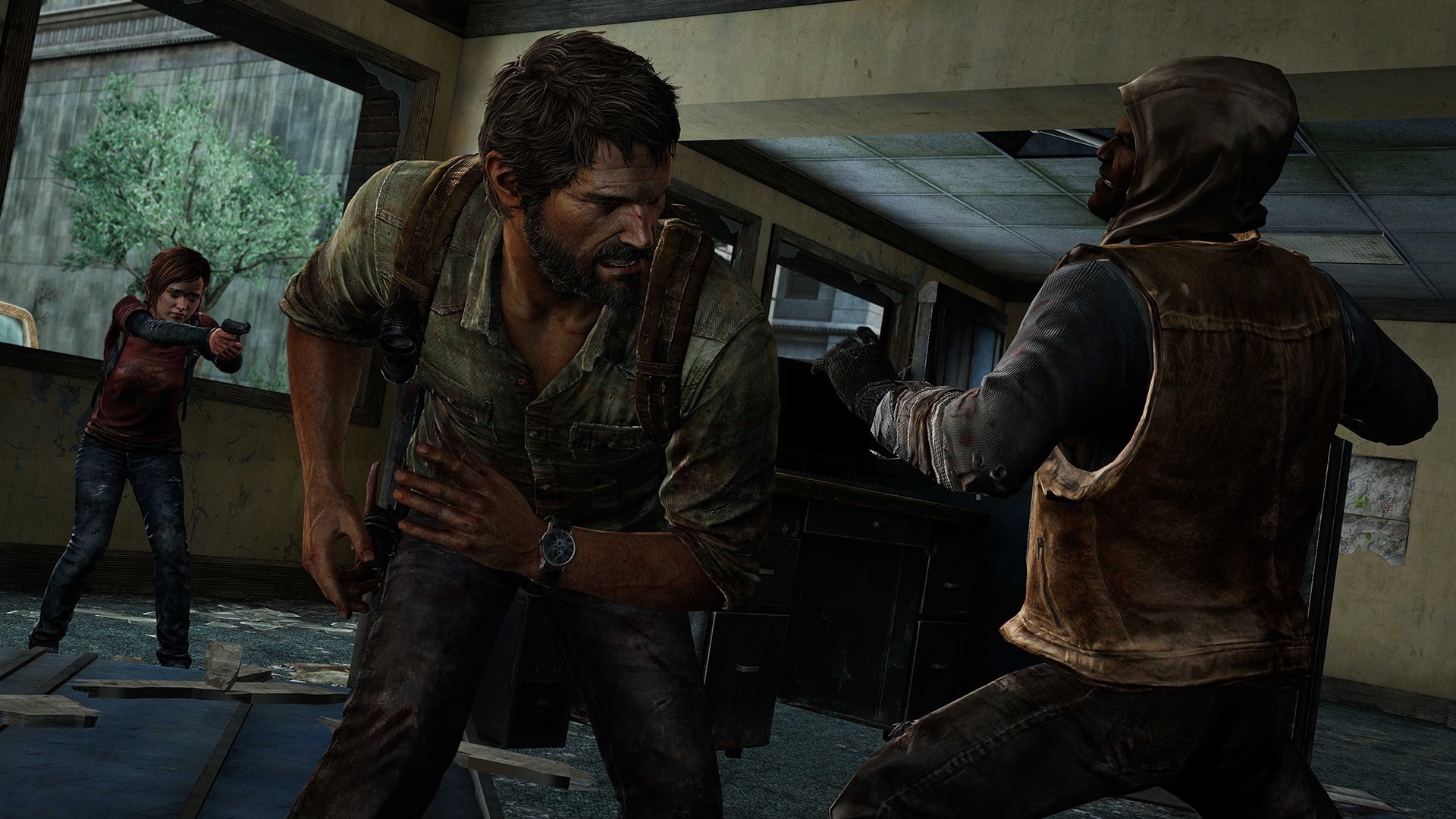

Uncharted 3’s combat is a well-mannered cousin to the brutality on display in The Last of Us. Unlike Drake’s adventure, with its glossy veneer of stuntmen going at it beneath bright lights, The Last of Us sees a frantic Joel pummel and toss society’s unsavory men - to kill as quickly as possible. It’s a turbulent tooth-and-nail tussle, but it recalls some of the lessons from Uncharted. It’s simple and button-mashy, with Joel pounding away and grabbing whatever he can, whether it’s a brick or glinting shard, to win. The spirit is in uncomplicated improvisation, like Nathan Drake, but with an outcome that illustrates savagery as opposed to wit. It’s apt for the dark, trampled civilization presented in The Last of Us, and it reorients melee combat around an important player choice.

The answer that Uncharted missed and gradually whittled out - and the answer that lies front and center in The Last of Us - is that it’s about the decision, not the act. It’s not about how you punch or when you dodge; those are decisions made in the aftermath. The crux of the combat in these games, instead, is in choosing to leave a place of safety and begin a brawl. You abandon your advantage, your impenetrable wall, and stand exposed and vulnerable to attack. But to time it just right and mash your way through is perfectly in line with that frantic spirit of last-ditch improvisation, as darkly motivated as it may be in The Last of Us. Both Uncharted and The Last of Us are ultimately about conserving cover - or protecting yourself from exposure - peering out only to shoot or cause a ruckus.

That sudden outburst usually comes after you’ve failed at sneaking through an area, which is lightly encouraged in the Uncharted series but absolutely vital in The Last of Us. That stealth tactics are “mostly optional” in Nathan Drake’s games is an iffy testament to their quality. Rather than the slow, meticulous movements you’d expect from more serious games in the genre, they do it quick-and-dirty, like the surprise birthday party version of stealth. Everything’s set up for your victims to walk into the scene, just going about their day, and then you yell SURPRISE by shooting everyone (It’s not the best birthday party, I know).

The deliberate setups in Uncharted 2 and Uncharted 3, with Drake entering the cordoned-off ruins of a temple or a splintering monastery at just the right place to remain undetected, seem to patch up some of the problems inherent in, well, being subtle in a shooter. It’s hard to keep track of enemies once they’ve moved (there’s no radar or on-screen cheat sheet to mark down targets), and once you’ve started a fight there’s no way to elude enemies and reverse back into a quiet, sneaky state of affairs. It’s really no wonder these mercenaries have been punished by the game-design god to look the opposite way at all times, even as they feel hero-breath on the back of their necks.

Stealth in The Last of Us is far more dynamic, less laid out with puzzle pieces and theatrics waiting to happen, and more likely to develop in a way that feels raw. The Last of Us introduces an elegant (albeit unreal) listening trick, allowing Joel to hunker down and gain awareness of enemy location, based on sound. And though this makes him more like a bat than an everyday man, the information is unobtrusive and allows you to plan your quiet route, winding beyond what the designers have suggested in the world’s layout. It’s also far more feasible, at least with human opponents, to run away, hide and wait for things to calm down.That safety net is crucial in games that adhere more seriously to the genre, and without it you feel like just one mistake is “playing it wrong.”

Though The Last of Us isn’t perfect in this regard, it does seem to fine-tune the balance that Uncharted also craves. If sneaking around is easier, clearer and more reliable, it becomes a resource - and less like a prelude to your inevitable screw-up. And when Drake or Joel do have to punch their way out of said screw-ups, it should feel ferocious and truly improvised. Their tones couldn’t be more different, but both Uncharted and The Last of Us thrive on a central character just scrapping his way through life’s perils. Uncharted couldn’t quite figure it out in its lifespan, but The Last of Us got closer than ever. Within that up-close combat, it almost works as the unofficial conclusion to Naughty Dog’s Nathan Drake Collection.

Ludwig Kietzmann is a veteran video game journalist and former U.S. Editor-in-Chief for GamesRadar+. Before he held that position, Ludwig worked for sites like Engadget and Joystiq, helping to craft news and feature coverage. Ludwig left journalism behind in 2016 and is now an editorial director at Assembly Media, helping to oversee editorial strategy and media relations for Xbox.