How making your own Doom level gives you better appreciation for the art of game design

I’ve played Doom for around 25 hours, yet I’m only three missions in. That’s because the bulk of my time has been spent in SnapMap, a built-in editor that lets you create your own single-player levels, multiplayer maps and mini-games. It’s a powerful tool, but has also been designed to be as easy to use as possible. Its name refers to how you snap its selection of rooms, corridors, arenas and chambers together, and you can have a completed level layout in minutes. That’s the easy part.

It’s when you start filling the map with stuff – weapons, power-ups, enemies, set-pieces, props – that you realise just how incredibly time-consuming and difficult level design actually is. It took me the length of some entire games to make a classic Doom-style single-player level, and it’s only 15 minutes long. I can only imagine how much effort and time it took to make something like BioShock’s Rapture. There are some limitations to SnapMap that I’ll get into later, but I’m fairly happy with the results. The map ID is B9MKXVBS if you want to play it yourself.

A lot of weird stuff has been created by the SnapMap community. People have made endless runners, a giant piano, a level where you can have a conversation with a Cacodemon, and even a basic remake of Harvest Moon. This is all made possible by logic chains, which let you create and run basic scripts in your level. A simple example of this is a door that, when opened, makes an enemy spawn. You drag a chain from the door to a hidden enemy, then set a trigger so that the second the player opens it, the enemy is made visible. It’s a really elegant system that doesn’t take long to learn.

But my goal was simpler. I wanted to make a challenging, polished, well-paced single-player level. I’ve been playing games for 20 years, and I’ve played more first-person shooters than I can count, so I thought I’d be able to pour all that experience into making something decent.

I started by drawing a basic layout on paper. I wanted to have a few big arenas linked by a network of corridors, and some branching paths that require the player to go hunting for a coloured keycard. Classic Doom stuff. Then I loaded up the SnapMap editor and began the surprisingly long process of turning that initial sketch into something enjoyable to play.

You don’t create your own rooms in SnapMap. Instead, you choose from a selection of pre-made ones and slot them together to create the layout of your level. This is the biggest limitation of the system, because you can’t go in and edit the geometry of the room to make it truly yours. Once you’ve spent a while in SnapMap, then play other people’s levels, you can’t help but recognise the same corridors, junctions, and arenas.

It takes me about ten minutes to recreate my sketch, however, and there’s enough variety of shapes and sizes to realise what I had in my head. I run through it a few times, without any demons, to get a feel for the place. I want every section to feel unique, and not just a bunch of boring sci-fi corridors. Although there are plenty of those too.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Now that the layout is done, it’s time to fill all those rooms with stuff to do. I begin by hand-placing demons. Only 12 can be active on the map at any one time, a problem that I have to get creative to solve. I make it so that all the enemies on the map are hidden, and only appear when the player passes through certain trigger points. This means I can have as many demons as I like in the level without hitting the limit.

Frustratingly, SnapMap doesn’t tell you about this at all. I had to find out about it online after enemies stopped appearing in my map. It didn’t take long to discover that other people were having the same problem. It’s a weird oversight in what is otherwise an intuitive, well-designed tool. After about an hour of careful placement, my level is full of angry demons waiting to be slaughtered. Easy ones in the first few rooms, slowly getting tougher towards the exit, and then a boss battle at the end.

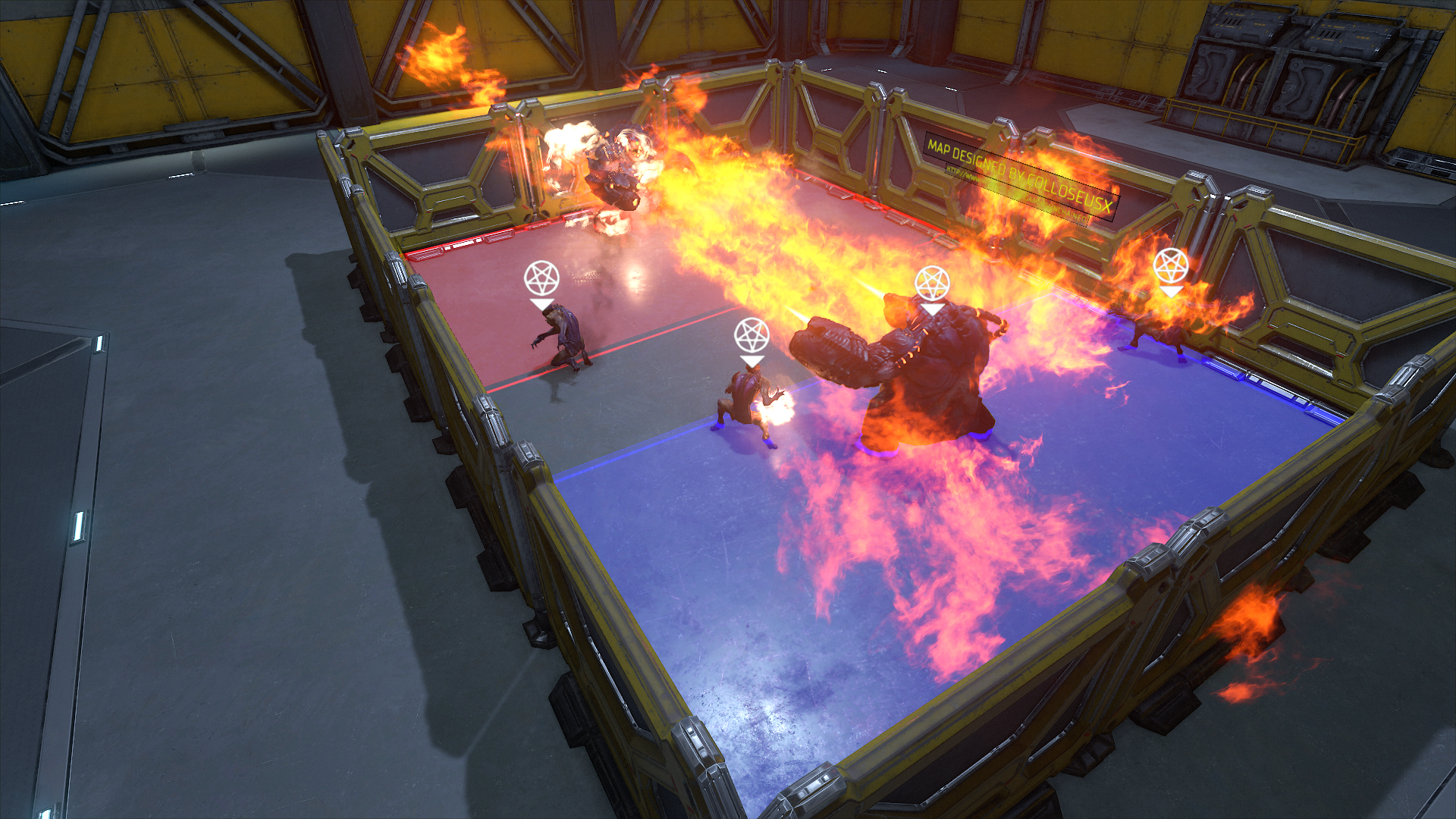

The boss battle takes place in a huge hangar, and comes in the form of two rampaging Cyberdemons. But after a few tests I’m aware that the fight is too easy, so I go back into the editor and boost their health and damage output. The room is empty when you first go in, to make you think it’s safe, but then I set a trigger slightly after the door to make the Cyberdemons suddenly appear. Doom has always played little tricks like this, and it makes the level feel more varied, even if the player can see them coming.

Elsewhere in the level I make it so that when the player picks up an enticing chaingun, a hidden wall slides away to reveal a pair of Hell Knights. Although I wonder if I should have chosen a better weapon, because a few players I’ve watched go through the level decided the gun they currently had was better and missed my trap altogether.

I also hide a secret room behind a fake wall containing a super shotgun. The door looks like a regular wall, and players will only find it if they press X next to it. To make locating it easier I drop a spotlight into the level and point it at the fake door to draw the player’s eye towards it. A classic, but subtle, level design trick. Most people who played the level missed the secret, but a handful found it, which makes it a success I think. The super shotgun should be a reward, rather than a regular weapon drop in the level.

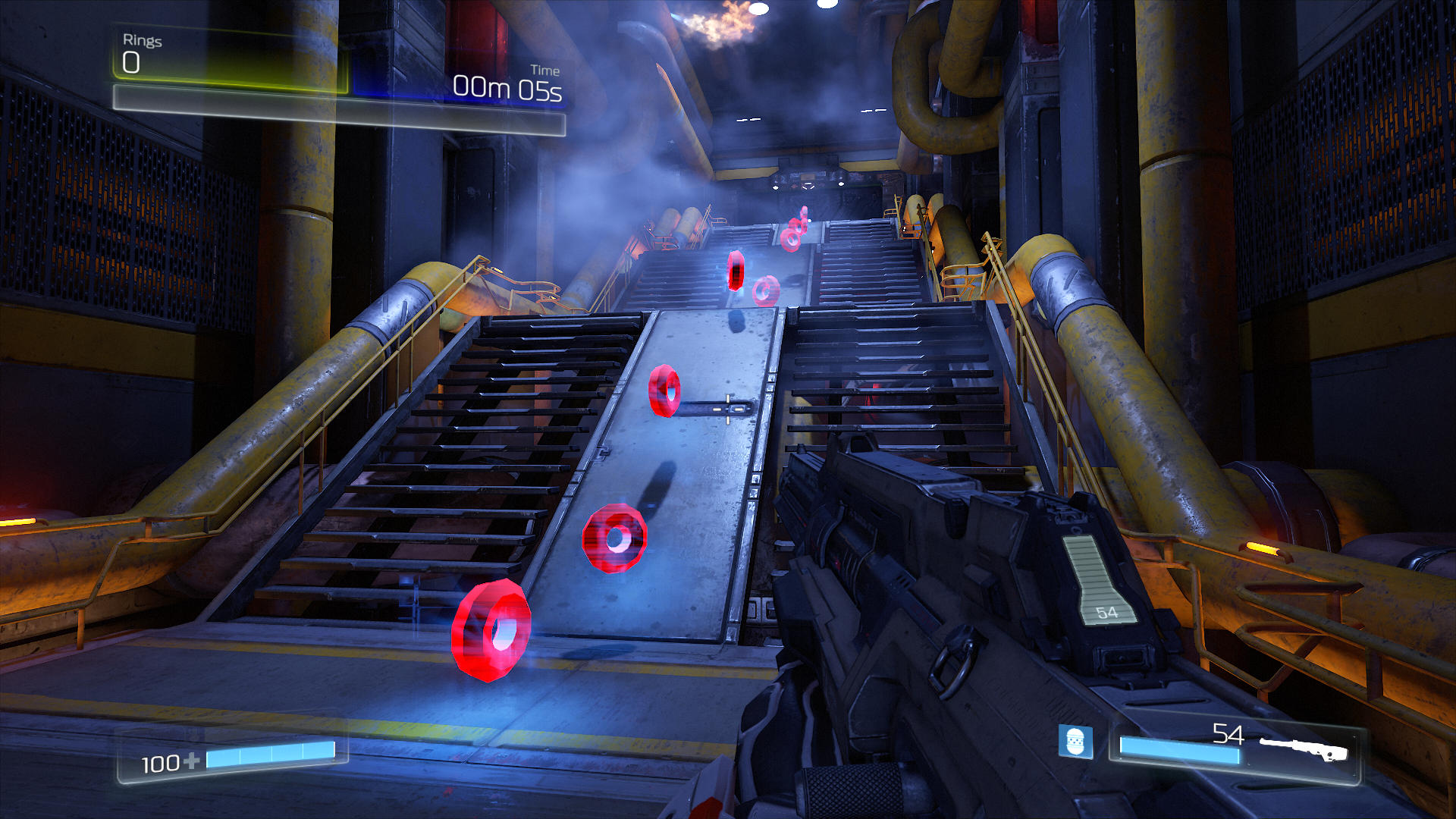

The last step is to add a set-piece. One of my rooms is a big multi-tier chamber, so I trigger a wave event when the player enters. This locks the door behind you then spawns several waves of increasingly tough enemies, and the only way out is to kill ‘em all. This is easier than hand-placing enemies because it’s all handled by the computer, and it’s different every time. Sometimes you get Cacodemons, sometimes you don’t.

I litter this room, and the rest of the level, with ammo, health, and armour. I don’t want the player to run out, because they’ll never be able to finish the level if they do. But I also don’t want them to feel spoiled. It’s a tough balance. And the more I use SnapMap, the more I realise that this is the hardest part. Getting it to flow. Having enemies appear at just the right time, making smart use of the level layout, dropping power-ups in the right places. I play my level so many times, tweaking this stuff as I go, that I become numb to it.

Level design really is an art, and it’s hard work too. My tiny, basic 15-minute level, created with easy-to-use tools, took me several evenings to complete. In the end the whole thing took around 10 hours. And now I have a newfound respect for game designers, because making a level that’s fun, challenging, and paced well is really, really difficult. I’m not 100% happy with my level – there’s a floating health pack in the boss room that gives me sleepless nights – but I still think it’s better than a lot of the stuff I’ve played on SnapMap. You can judge for yourself when you play it.

This article originally appeared in Xbox: The Official Magazine. For more great Xbox coverage, you can subscribe here.